Volume 19, 1953

All material courtesy of the National Park Service. These publications can also be found at http://npshistory.com/

Nature Notes is produced by the National Park Service. © 1953

Crater Lake Discovery Centennial

Gold! Gold! That cry rang across the United States in the late 1840’s, and Mr. Wesley Hillman heard the call and responded. He set out for California from New Orleans in 1840 – – taking his young son, John, along (see inside Front cover). The party followed the Old Immigrant Trail and crossed the Rockies via the South Pass. Young John later recalled seeing thousands of buffalo and remembered the stampedes. Three months passed before the group reached the area where the waters flow west. Soon they arrived at the Columbia River and used it as their avenue to the West. Mecca of the West at this time was San Francisco, as for thousands of prospectors, the destination of the Hillmans. An exciting trip along the coast on various craft carried John and his father to San Francisco.

John Wesley Hillman soon departed from his father to search for a strike that could bring wealth in a day. Having only moderate success as a prospector, John Hillman shifted from job to job for the next three years. While driving mules for an ungrateful, penny-pinching, pioneer business man, John Hillman received word of a California party secretly purchasing supplies near his home in Jacksonville, Oregon.

A prospecting party quickly organized and decided to follow the California group on their search for a rumored fabulous Lost Cabin Mine. The Californians soon realized they were being followed and began scattering through the brush, camping in inaccessible areas and using a series of other pioneer tricks in the attempt to shake off the pursuing Oregonians, but to no avail.

One June day in 1853, when both parties had scattered and were searching for landmarks which would lead them to the mine, John Hillman approached close enough to bid one of the Californians a good day. Soon after this incident the groups settled their differences and united. Supplies of both groups were low so it was decided to allow three men from each party to gather as many provisions as possible and make one final search for landmarks.

On June 12, 1853, this group, including John Wesley Hillman, climbed the west slope of the mountain now called Mazama and became the first white men to gaze upon this circular sea of indigo later to be named Crater Lake. John Hillman stated that if he had not borrowed an exceptionally fine mule from a friend, he would not have been the first man to see the lake. Hillman was so surprised to find a lake he had noticed in the distance that he failed to look down; his mule suddenly stopped and he was about to spur the animal when he glanced over the rim an noticed the 1,000 foot drop. Had his mule been blind someone else would have discovered Crater Lake!

Hillman Plaque |

Recovering from the initial impact of finding this unusual lake, the group assembled and two names were suggested. Mysterious Lake and Deep Blue Lake were voted on and the latter was chosen as the first name of the Lake. Hillman suggested descending to the water’s edge, but his exhausted and hungry companions vetoed this idea and the group started home to Jacksonville. The excitement of Indian wars and the discovery of gold, plus the fact that there was no newspaper published in the area allowed their discovery to be quickly forgotten.

The United States was well launched into the Civil War by the year 1862. Prospectors, settlers and westerners were hardly affected by the war and it was in that year that Chauncey Nye and his party were heading south from the John Day Basin area in search of water. They came upon the rim of the Lake and thought of using it as their source of water. However, they decided to use melted snow for their water supply, as they soon realized the tremendous distance to the water.

The Nye party drew a crude map of the area as they moved around the rim and they called the Lake simply Blue Lake. Enroute to Jacksonville, Chauncey Nye and three others noticed a very rugged peak which they climbed and named Union Peak. A majority of the group favored the Union cause in the Civil War and they hoped the name of this volcanic plug would never change. Following the usual slow route of travel to Jacksonville, Oregon, the Nye party reported their discovery and on November 8, 1862, in the Oregon Sentinel, the first printed article about the Lake appeared.

The Civil War had spread to the West to a considerable degree by 1865, both the Confederacy and the Union Army having sent men to the West in search of horses. Captain B. F. Sprague, Company I of the 1st Oregon Infantry, had been detailed to build a road from Fort Klamath to Jacksonville. He sent F. M. Smith and John Corbell to hunt game in the area because the fresh meat supply of the Company was getting low. While on this hunting trip, these two men came upon the Lake. They returned and told of their discovery. This news was passed on and so excited several members of the Company that they decided to visit the Lake at their earliest convenience.

Meanwhile, the Snake Indians in the Steens Mountain area had one of their frequent uprisings. Captain Sprague and five volunteers headed for the troubled territory and decided to visit the mysterious lake on their return. Captain Sprague suggested that the group descend to the water’s edge and a friendly race soon developed, Orson Stearns being the victor. Since Stearns was the first to reach the water, he was given the honor of naming the lake. With appropriate ceremonies it was called “Lake Majesty”.

In the course of the next four years, reports reached many scattered towns and settlements concerning this large sunken lake and the lonely island cinder cone on which the foot of man had never trod. Our early western settlers had a spirit of adventure found only in an energetic and colonizing group. These reports excited John Sutton, and in 1869 he organized a party with the specific purpose of visiting the Lake, Carrying a knocked down boat which they assembled at the shore of the Lake, they rowed over to, named and explored Wizard Island. The Sutton party wrote an account of their trip, placed it in a tin can and left it in the rocks of the island’s crater. After exploring the island they decided to sound the Lake. They made several soundings, but soon decided their craft was too frail for such a job. From those taken, however, they estimated the lake to be 2,000 feet deep and later official soundings indicated they were very nearly correct.

John Sutton’s patty christened the blue waters “Crater Lake” and also took the first photograph of the lake. In 1872, Crater Lake was visited by the Applegate party, which included Leslie M. Scott, Lord Maxwell of Scotland and Dr. Munson. Applegate Peak and Munson Point were named by this party.

Hillman, Nye, Sprague and Sutton are names important in the discovery of Crater Lake, but the development of this area was to rely on a man of steel convictions, William Gladstone Steel, later to become known as the “Father of Crater Lake National Park”. His association with Crater Lake began as a boy in his teens. Will carried his lunch in a newspaper rather than a dinner pail because he did not like carrying a cumbersome pail five miles home from school each day. One noon, forced inside by inclement weather, Will Steel was reading various articles in a newspaper wrapped about his lunch when his attention focused on an article of a mysterious lake in a crater somewhere in Oregon. Will Steel read the article over several times and while walking home to the ranch in Kansas the curiosity and desire to visit this mysterious lake increased with each step. Once home, he talked about that lake continuously and eventually resolved to see it.

He never forgot this boyhood vow and when, at the age of eighteen, his family moved to Portland, young Will Steel immediately started a search for information about the lake. It was not until four years later that the information necessary for a visit to the lake was found. William Steel was employed at a local publishing firm when C. E. Watson stopped in the office to visit a friend and told of his visit to the lake. Of course, Will Steel obtained all information possible. He learned of two ministers planning a visit to the lake and asked to join the group.

In 1885 Will Steel finally saw the watery gem of the Cascades, the rim and the Lake, a place he was to know so well that it was to become a major part of his life. Humbled and inspired by the heavenly blue color of the lake, he soon conceived the idea of preserving this area for all the people, for all time. A national park there was the dream of William Gladstone Steel.

“What was necessary to develop this area into a national park?” he asked himself. Most important at this early date was the publication of its beauty, to announce its grandeur and then to establish its location. Closely connected with these steps were the publication and improvement of the routes of accessibility. To those few who had visited the area, the beauty and the glory of nature’s handiwork were as impressed on their thinking as the effects of the master architect, erosion, or the results of glacier and volcanic action evident everywhere in the vicinity of the lake. William contacted these people and asked them to contribute articles to various organizations concerning these wondrous sights and, more important, information establishing the definite location of available routes to the lake.

William Gladstone Steel |

The enthusiastic spirit of the people contacted by Mr. Steel soon made Crater Lake the most visited scenic wonder in Oregon. One needs little imagination to realize that William Steel’s next problem was to bridge the gap between Washington, D. C. and Crater Lake. National parks are established by a Congress in Washington, and Will Steel attacked the problem with great vigor, writing a petition to President Cleveland explaining the natural wonders of the region. On August 21, 1886, ten townships including Crater Lake were withdrawn from public sale. This same year, Captain C. E. Dutton and party, coupled with the work of Professor J. S. Diller in 1883, did a great deal to familiarize Washington Congressmen with the geologic wonder of Crater Lake. Officially establishing Crater Lake’s depth at 1,996 feet, the deepest lake then known in North America, was news of national importance.

Writing thousands of letters, organizing petitions, seeking prominent citizens’ support and carrying on the battle of the Cascade Forest Range and its closely aligned fight with ranchers and lumbermen who could only look at the forest with “board feet” eyes were some of the unpaid tasks carried on by Will Steel.

Since the first discovery of the lake, men had wondered if there were fish in Crater Lake. In 1888, Will Steel was enroute to the lake on one of his many visits to explain some of the numerous outstanding features to guests, when trouble caused the group to stop at the Gordon Ranch The Gordon boys collected 600 fingerling trout, which Steel purchased. Steel began the forty-nine mile trip to the lake, stopping at each fresh stream to change water. As he neared the rim, several fish began to die and at the time of the planting only thirty-seven remained alive – – but the first fish had been stocked in Crater Lake.

On May 22, 1902, Crater Lake was established as our fifth national park and Steel’s efforts were rewarded. On October 13, 1902, W. F. Arant became the first Superintendent of Crater Lake National Park, appointed by Secretary of the Interior Ethan A. Hitchcock. Arant’s first and most important contribution was the improvement of roads. This was the beginning of an ever-improving highway system in the park. This was not the end of work for William Steel, for he threw his weight behind the effort of developing roads and lodging for visitors. In 1913, he became the second Superintendent of Crater Lake National Park. Much personal time and money were sacrificed by him in the improvement of the park.

The advent of the horseless carriage was of critical importance at Crater Lake and a suggestion was made to build two roads to the rim, one for horses and the other for the noisy automobile. In 1907 the first cabinet member visited the park, James R. Garfield, Secretary of the Interior. Several years later, in honor of his visit, Garfield Peak was named. 1907 was a year of firsts, the first public boat, the Wocus, having been launched on Crater Lake at that time also.

In 1912, the lodge was erected and one unit of it is the oldest structure now existing in the rim area. 5,235 visitors were recorded in that year. Seven years later, the rim road around Crater Lake was completed and visitors had increased to 16,645. The plaque in honor of John Wesley Hillman was dedicated in 1925, and three years later the Crater Wall Trail was completed. By 1931, the new standard grade road was in operation, Sinnott Memorial was dedicated and visitors totaled 170,284 during that year. In 1953, 332,835 persons came to the park.

In Crater Lake National Park we have commemorated within one year of each other, a centennial and a semi-centennial – – last year the fiftieth birthday of the National Park and this year the one hundredth anniversary of its discovery. The history of the park does not end with these, but rather will continue to reflect the broad-minded concept of administration initiated with Will Steel’s dream – – to conserve the scenery, the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein and provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as to leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.

Selected References

Arant, W. F. 1904. Report of the Superintendent of Crater Lake National Park to the Secretary of the Interior.

Carey, Charles Henry. 1922. History of Oregon.

Fremont, John Charles. 1887. Memoirs of my life.

Gorman, M. W. 1897. Discovery and early history of Crater Lake. In Mazama.

Gray, W. H. 1870. History of Oregon.

Steel, William Gladstone. 1914. Report of the Superintendent of Crater Lake National Park to the Secretary of the Interior.

______, 1885 – 1934. Eleven volumes of scrapbooks containing numerous clippings, telegrams, and correspondence concerning Crater Lake. Also his correspondence file concerning Crater Lake National Park. In the files of the Park Naturalist, Crater Lake National Park.

New Bird Record

Last spring, a species of bird was recorded that not only was new to the park list, but it was found under most unlikely circumstances. During a light snow storm, while skiing at the upper headquarters residence area, April 6, 1953, at 6:13 p.m. the writer observed an American coot, Fulica a. americana Gmelin, often known as “mud hen”, denizen of marshes, ponds and lakes.

The locality was where the driveway of the residence of then Park Engineer Robert Hursh connects with the main residential road. The bird flew slowly past me, about four feet above the surface of the road, so that the white frontal plate was clearly visible. It came from the east, landed outside the Hursh garage door, then walked inside. Mrs. Hursh, who is also familiar with the species, saw the bird there and agrees with my identification.

The next morning, the bird had gone and there was no evidence that it had eaten any of the water-soaked oatmeal provided for it by Mrs. Hursh the night before.

Lost Creek Ski Patrol

Each year a crew of rangers makes a patrol to the Lost Creek Cabin (East Entrance). This patrol is made primarily to remove the snow from the roof of the cabin, which would otherwise be crushed. The total depth of snow to be removed has varied from a record of eleven feet, in the spring of 1952, to a low of four or five feet. This year the depth was approximately seven feet.

The morning of February 11, 1953, was clear and cold – – ideal weather for a ski patrol. I say ski patrol; actually we used a Tucker Sno-Cat as much as possible. On the trip to Lost Creek it is possible to use the Sno- Cat for four miles, thus leaving three miles to be skied.

The rangers on the patrol this year were Paul Turner, Verne Bertsch, and Richard Ward. We left Park Headquarters at 8:00 A.M., in the Sno-Cat and proceeded out the East Entrance road to the Vidae Falls truck trail. We then traveled this road to the point where it starts around the flank of Dutton Ridge. Here we parked, took time for a cup of coffee, put on our skis and started around the ridge.

The day was beautifully clear, so the three of us were busy taking color shots of Union Peak, Klamath Lake and other interesting features. About one and a half hours after leaving the Sno-Cat we reached the point where the rest of the trip was downhill. Here we stopped for lunch, as it was almost noon. We also took several pictures of Mt. Scott with its covering of snow. We always look forward to that stretch of the trip from Dutton Ridge to the Lost Creek Cabin as it is downhill all the way. (I make the above statement only from the standpoint of “going over” because “coming back” the slope seems ten times steeper up than it does down.) We put on our skis after lunch and started down. Luck was with us as we had almost ideal snow conditions. At first we encountered a few patches of ice, but we soon worked our way out of it onto a stretch of powder snow about three inches seep, arriving at the cabin early in the afternoon.

The first job was to dig out the stove pipes and to shovel the snow from the cabin door. Finding the stove pipes was a big job in itself. We knew approximately where they were, so we started digging. After removing about seven feet of snow we found the ridge; then we started down the slope of the roof and, as the snow had pushed the pipe over, we had to search for it. This took some more digging. By the time the pipe was dug out and straightened we had worked up an appetite. While the stove pipes were being dug out, one man gained access to the door of the cabin and laid the fire. At the signal that the pipes were clear, the fire was started.

Ranger Bertsch standing in the initial cut in the snow. |

The cabin was like a deep freeze when we first went inside, but after a few minutes it started to warm up and all thoughts turned to food. Each man picked his specialty and started to cook. The food had been stored late in the fall in mouse-proof containers and, although many of the items were frozen, it was in good condition. After a good meal, the dishes were washed, more snow shoveled, beds were made, fires were built up, and then to bed.

Next day the routine was as follows: Up in the morning, after some discussion as to who would get up and build the fires and start breakfast (hot cakes and bacon). After breakfast snow removal. We divided the roof into sections and shoveled trenches all the way to the roof, eave to eave and over the top; then using a saw, sections were cut off and rolled clear of the roof. This soon becomes back breaking work. The snow removal continued all day, with short breaks for coffee and lunch.

As soon as it started to get dark we had dinner of wieners, potatoes, peas, biscuits with butter and jam, and peaches – – all washed down with lots of coffee. We all “hit the sack” early – – to rest our sore and tired muscles.

The morning of the third day we were up bright and early, ate breakfast and finished the roof. We had an early lunch, put out the fires, locked the building, put on our skis and started back up the steep mountainside to the Sno-Cat. For this climb we used “seal skins”, a mohair material fastened to the ski bottoms that allows a skier to climb a slope without sliding back. After several hours we reached the top of Dutton Ridge and had a candy bar and a cup of coffee. We only had a little way to go now, with some excellent downhill skiing. Soon we saw the Sno-Cat – – and it was a welcome sight. Ranger Turner started the motor, we had another chocolate bar, and then settled back for a comfortable ride back to Headquarters.

The Marten and the “Mac” Marmots

I was set up to take pictures of a young marmot whose talus slope burrow is located north of Llao Rock. On several earlier visits I had found the young fellow to be sufficiently curious or uninitiated that he would come out of his underground home, looking up toward me from his ridiculous sitting position with his little round belly resting on the ground between his not-long-enough hind legs. My little friend had sat like this several times in the past, with forepaws held primly in front of him, looking toward me with as much interest, it seemed, as I showed toward him.

However, on that day all was not well on the precipitous marmot rock pile. The little fellow came out within minutes, but two adults – – some 60 feet distant – – were constantly giving the alarm cry of the yellow- bellied marmot. Their cries could, I thought, be directed toward me. No, there was a red-tailed hawk sailing slowly overhead; this was probably the cause for the marmots’ unusual display of alarm. The short, shrill cries continued, though, long after the hawk had disappeared far east along Crater Lake’s rim toward Cleetwood Cove.

Then, without warning, a small mink-like head, rich brown in color, peered from behind the large rock just below the young marmots’ hole. It was a pine marten, fearless, pugnacious animal, smaller and more slender than a domestic cat.

The young marmot disappeared into the burrow; the marten, after a hasty look about, which included a glance in my direction, followed. After a few seconds, the marten reappeared and for a time was lost among the rocks. Once more I saw my little friend’s nose with its knowing expression. But the sharp, warning cries of the two adults, sitting up like overgrown golden-mantled ground squirrels, sent the young fellow back out of sight.

Once again the marten appeared, eyes gleaming, head bobbing. He entered the young marmot’s burrow, this time coming out of another exit. Smelling the rocks about the area, he once again gave me a fearless glance – – a glance that made me feel the tenseness of the moment acutely – – before he again slipped into the main entrance.

After many seconds, the marten reappeared and poised on the large rock with my little friend clenched shapelessly in his jaws. Quickly now, the marten carried his prey down the rocky slope and across a small pumice meadow to the shadow of a Shasta red fir. Here the marten put down the marmot, looked toward me and toward the two adult marmots, his body vibrating intensely. Then, picking up his plunder, the marten disappeared into the depths of the forest.

Now one of the adult marmots went into action. Whether my presence had prevented earlier defensive activity or whether they had not actually seen the marten, there is no way of determining. I had thought of the marmot as a slow animal, moving lazily about on its short legs. This conception was soon to be altered, for this adult covered the 60 feet of rough terrain between his burrow and that of the young marmot in a matter of seconds. On arrival he sat up and gave three shrill “chirps” before dropping into the burrow, tail bristling so strongly that it approached the size of his fat body. The adult marmot soon returned, sat up straight for an instant. Then, with the bristling tail trailing like a pennant, he returned to the home burrow as quickly as he had come.

For the next ten minutes both adults sat upright, giving their shrill chirp every few seconds. One of the adults began to run toward a pile of rocks that stood on the edge of the pumice meadow and, to my surprise, a marten dodged from behind one of these rocks. The marten sped from the lumbering marmot with a swift airy grace, possibly very soon, by taking to the trees, to complete his escape.

Impressions of Crater Lake

What is Crater Lake? How does it affect you? What do you see when visiting it for the first time? The answers to these questions would undoubtedly be as varied as the people giving them, but a general picture would emerge – – an overall impression of beauty and power.

It has long been a conviction of mine that we sometimes become so immersed in a small segment of nature or life that the total picture is lost to our view. Certainly here at Crater Lake, because of the structure of the Park, a full comprehension is more easily gained from one point than in many National Parks. Yes it is ultimately made up of numerous impressions absorbed while watching and studying this outdoor museum. Rather than become engrossed with one of the specific, minute segments of this unique scene, I prefer to view it as a whole, discovering for myself the aspects which unite to form a panorama which has brought many people to think of Crater Lake as the “eighth wonder of the world.”

Looking at the Lake for perhaps the first, perhaps the hundredth time, we are unceasingly impressed by the roundness of this caldron of deep blue water, by the steepness of the slopes delineating the Lake, by the intense color of the waters accented by the green hemlocks and multicolored rim and by a sensation of height and space gained from being on top of a collapsed mountain.

In watching this “thing of rare beauty, resting in a circular crater of a great volcano,” we become increasingly aware of a unity of form, pattern, and color – – – “a symphony of line.”

Forms that immediately draw our attention are: Llao Rock, whose massive face forms an imposing feature of the rim wall from any vista; closer examination reveals the volcanic source of this “bird of fire”. Wizard Island, whose shape inspired the belief among early travelers that monsters might live on this volcano within a volcano. The trees, uniformly arranged in line patterns against the gray and black cinder, catch the evening light as it glances golden across the southern face. Hillman Peak, whose sharp, unicorn-like point is the highest on the rim wall, creates many varied impressions of form and color as light and shadow play upon the jagged spires, remnants of an age-old vent from which once spewed molten materials from deep within the earth. Delicate tints of red, lavender and black emerge at various angles and in varying lights. And, last but not least, the Phantom Ship, whose so illusive, and yet so majestic, shape has aroused the casual visitor and the ardent scientist alike to wonder about the story which lies bound within its rocky masts and wing-torn sides.

Line and pattern add to the picture: The frivolous wind ripples playing constantly about on the surface of the Lake create an ever-changing pattern; reflections of the steep rim walls and passing clouds add soft line and color; layers of long-erupted lavas parallel the sky as huge rock slides reach skyward from the water; and light and shadow produce shifting contrasts.

All of these impressions add to our awareness of distance, size, and scale. John C. Merriam expresses the idea that “The sublimity, power, and orderly operation in this process of creation develop in us reactions produced by other elements which we recognize as beauty and harmony”.

The finishing touch to our impressions of beauty born of form, line and pattern is color – – color born of light as it reflects from the steep walls and deep water; color which at first is not apparent, so subtle is its effect upon our view. But, as we continue to look at this incomparable scene, we begin to see myriad hues within the frame of this “deep Blue Lake”.

The primary color, and the only color evident to many, is Crater Lake Blue. So blue is it that one feels it cannot be real! But the Lake varies in shade from pale, baby blue where the horizon is reflected, to a somber midnight blue when, near sunset, the cliffs cast their dark shadows upon the waters. Thus, since the origin of these colors is dependent mainly on light, as the light changes so does the blue.

The pastels of the rim contrast strikingly with the intensity of the water and serve well to enhance its beauty. Such are the vivid pinks of Dutton Cliff, the softer hues of Red Cloud Cliff – – startlingly accented by the tile red of Pumice Castle; the brilliant golds and browns of Garfield Peak and Chaski Slide which turn to turquoise the water of Eagle Bay; the somber grays and blacks of Roundtop and Palisades which form a fitting backdrop to vivid curstose lichens of chartreuse, orange, blue-gray and black. A symphony of gray rises from the andesitic and dacitic flows of Mt. Mazama – – in Llao Rock, Palisades, Roundtop, and the cinder of Wizard Island, Red Cloud Cliff, Sentinel Point, the many layers of Dutton Cliff, Phantom Ship and those transient summer visitors, the thunderheads. And over all the rim lies the light tan of pumice flows, a neutral color which ties together all in peaceful harmony of line and color.

To this picture painted in rock, water, sky, and wind are brought each summer the fleeting colors of wildflowers as they make their ephemeral display within hitherto unnoticed crannies of rock, on forest floors and in pumice flats. Prominent among the eye-catchers are the smooth wood rush whose yellow-green shoots spring through shallow snow in their eagerness to become a dense green carpet beneath the hemlocks; the rock-loving penstemon whose showy, trumpet-shaped flowers make a blaze of color on overhanging ledges; the spreading phlox whose petals shade from white to deep lavender, making a patchwork quilt of the open pumice slopes; the Indian paint brush whose gaudy crimson heads wave merrily in the wind; and the Lewis’s monkey flower whose more demure shade attracts ardent rufous hummingbirds for a drink of nectar.

And so these impressions flow and change, but constantly build an abiding feeling of serenity and an increasing awareness of the magnitude of the creative Power, which guides us all. We might say, as did the poet, Ernest Moll,

“Untouched by thought, I give myself to these

Rich intervals of blue and rose and grey,

Free as a white-winged ship that sails the seas

Knowing no port nor and homing – day.”

References

Merriam, John C. 1938. Published papers and Addresses of John Campbell Merriam. Volume IV. Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, D. C. pp. i-vii, 1947-2672.

Moll, Ernest G. 1934. In: Ranger – Naturalists Temporary Manual of Operation. Field Division of Education, Berkeley, California (Mimeographed). 109 pp.

Moll, Ernest G. 1935. Blue Interval. Metropolitan Press, Portland, Oregon. 41 pp.

Crater Lake Wildflowers and Their Rapid Growth

At elevations from 6000 to 8000 feet, like those near the Rim of Crater Lake, winter weather exists during a major portion of the year. Records kept in the Chief Ranger’s office show snow on the ground from October until June with snow often recorded in September and sometimes remaining until July. Compared with the season of 1951 – 52, when snowfall was almost a record, the total reaching 835 inches, (Hallock, 1952) only 571 inches were recorded for the year of 1952 – 53. Of this amount, 6.8 inches fell in June and approximately 108 inches remained on the ground at the Rim Campground July 1st. Hence the late season. The Rim road around the Lake was not completely opened until July 30th and the trail to the Lake, August 1st.

On the bank bordering the Sinnott Memorial walk, snow disappeared July 10th. Twenty days later, prickly currant, Ribes lacustre Poir, had put on new leaves and a profusion of greenish pendulous flowers.

The smooth wood rush, Luzula glabrata Hoppe, cannot wait for the snow to melt but sends up bright green, grass-like leaves through the thinning snow, often while it is three inches deep. This plant is a perennial, the stoloniferous stems staying alive underground during the long winter months.

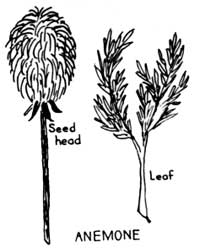

The western windflower, Anemone occidentalis Watson, is not-able for it’s quick appearance when the snow melts. In less than a week the finely divided leaves appear, and two weeks later the flower stem is crowned with a white flower, the center filled with canary yellow stamens. This in turn is short lived, and the attractive greyish seed head, resembling a wind blown cloud, takes its place. Like so many members of the buttercup family, the flower has no petals – – the showy sepals taking their place.

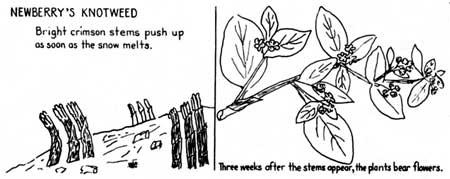

For speed in completing its annual cycle, one must mention one of the commonest of Crater Lake flowers, Newberry’s knotweed, Polygonum Newberryi Small. The history of several recorded plants on the Garfield Peak trail was as follows: Two days after the snow melted back, bright red stems pushed through the drying soil. A week later green leaves were in appearance, and the plant was about three inches tall. Seven days later, short spikes of greenish flowers were showing, and the plant had attained the apex of its flowering season just 24 days after the bright red stems pushed through the earth. Very quickly the green chlorophyll in the leaf disappears, and the hillsides are brightened by the red and orange tints of this fast growing little knotweed. This is just another of the many plants which take advantage of the brief hours of summer sunshine to complete their short yearly cycle before autumn frost and snow terminates activity for another year.

Reference

Hallock, Louis W. 1952. The big snow of 1951-52. Crater Lake Nature Notes 18:3-5.

Observations and Census of the Black Bear in Crater Lake National Park

Crater Lake Bears. From kodachrome by Welles and Welles.

Crater Lake Bears. From kodachrome by Welles and Welles.

The Olympic black bear, Euarctos americanus altifrontalis (Elliot) was first noted at Crater Lake from the standpoint of numbers in 1896 when a biological survey was made of the mammals in this area. At that time the black bear was reported to be uncommon (Merriam, 1897). According to one ranger naturalist, bears were so scarce at one time that it was feared they would become extinct in this area. It seems, however, that in 1919 hopes for their survival took a turn for the better when a long, starved-looking female bear put in her appearance (Wynd, 1930).

She soon gave birth to a pair of twins and, after rearing them to the independent stage, wandered off one day to a nearby logging camp. Having learned to place her confidence in human beings, she sat down by a tent and waited to be fed–but instead of food she received a lead slug. The twins, named Jemima and Buster, carried on successfully and are said to be the forerunners of most of the bears now found in the park.

The total number of bears observed in the fall of 1933 was fourteen. This census was taken after the first heavy snowfall, at which time the bears relied on food scraps obtained at the dining hall near park headquarters (Canfield, 1933). According to Wallis (1947), Wildlife Ranger Wilfred Frost observed forty-two bears on August 31, 1939. Thirty-three were black, the remainder being of the brown color phase. Wallis himself estimated the bear population in 1947 to be between twenty and thirty in number. From the foregoing records it is evident that the census of bears during the past 50 years is rather incomplete and lacks data in regard to methods used, percentage of various color phases and any breakdown into age groups.

Cinnamon Cub. From kodachrome by the author. Cinnamon Cub. From kodachrome by the author. |

“Where can I find a bear?” “How many bears are there in the park?” Questions such as these stimulated me to pursue an active program of observations on the bears in the park. During the summer months of 1953 daily records were made in regard to size, color, number and habits.

Although the National Park Service long ago discontinued bear feeding “shows” and prohibits the feeding, teasing and molesting of bears, with the welfare of both bears and visitors in mind, the animals are occasionally seen crossing the roads in various places in the park. They frequently wander through the campgrounds looking for food that may not have been packed away in a secure place. The bear is not a rare mammal in Crater Lake National Park.

The following table is a record of the quantitative results obtained. To obtain this data a segregation plan was used. First, the several females and their first year cubs were segregated, the second year cubs were then differentiated from medium and full size single adults. Daily observations included many repeats which were hard to distinguish at first but soon various differentiative characteristics such as general size, obesity and sex became helpful in individuals within a given category.

It should be understood that by no means do I consider this to be complete because such a field census undoubtedly includes some duplication, and some bears would go unobserved in an area covering two hundred and fifty square miles. However, this is an attempt to start filling in a gap that can be added to from time to time as better methods and additional observations are employed.

| ADULTS | ||

| No. | Size | Color |

| 8 | Full grown | Black |

| 6 | Full grown | Brown |

| 4 | Medium size | Black |

| 4 | Medium size | Brown |

| 22 | ||

| CUBS | ||

| No. | Size | Color |

| 5 | First year | Black |

| 7 | First year | Brown |

| 1 | First year | Cinnamon |

| 3 | Second year | Black |

| 3 | Second year | Brown |

| 19 | ||

Total 41

The only record of a bear observed nursing her young in the park prior to this year was made in 1939 by Mr. Frost (Wallis, 1947). He observed a mother bear nursing triplets near one of the disposal areas. Ranger Naturalist John Mees observed a mother nursing her twins in June, 1953 According to Mees, the mother bear assumed a prostrate position by lying on her back; then with the help of her front paws the two young were arranged in orderly fashion on her ventral side for nursing. Mr. Mees observed them from a distance of fifty yards and noted that loud gurgles could be heard that far away.

As can be seen in the table, which notes the number of bears observed, there was apparently only one cinnamon cub for the 1953 season. This little cinnamon bear had a black twin which was considerably larger. One day the mother crossed the road and, since the snow banks were rather steep on either side, the cubs had to really scramble to climb over them. In fact, the poor little cinnamon could hardly make it up. He rested about half way up one bank and then made it on the second attempt. Since he was not seen again during the season, I wondered if some male bear had killed him.

Two of the full grown male bears, one black and one brown were very conspicuous because of their unusually large and seemingly long front legs. Several of the park staff noted this unusual anatomical feature. The older males also have very large, hard-looking heads which one cannot mistake in trying to segregate the groups.

References

Canfield, David H. 1933. A Bear Story. Nature Notes from Crater Lake National Park6(1):8-9.

Merriam, C. Hart 1897. The Mammals of Mount Mazama. Mazama 1(2): 204- 230.

Wallis, Orthello L. 1947. A Study of the Mammals of Crater Lake National Park. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Oregon State College, Corvallis. 91 pp.

Wynd, F. Lyle 1930. Triplets. Nature Notes from Crater Lake 3(1):2-6.

Other pages in this section