History of Rim Drive, Crater Lake National Park

This “History of Rim Drive” is part of the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) study of Crater Lake National Park Roads, HAER No. OR-107. HAER (Eric DeLony, Chief) is a division of the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. This project was funded by the Federal Lands Highway Program, administered by the U.S. Department of Transportation, through the NPS Park Roads and Parkways Program. Fieldwork, drawings, and photography were completed under the direction of Todd A. Croteau, Program Manager, and Tim Davis, Program Historian. The recording team consisted of field supervisor and historian Christian Carr (Bard Graduate Center) and architectural technicians Sarah Lehman (University of Oregon), Walton Stowell (SCAD Savannah, Georgia), and Simona Stoyanova (ICOMOS, Bulgaria). Jet Lowe of HAER produced the accompanying large format photography. Stephen R. Mark, Historian, produced the historical report, which was edited by Justine Christianson, HAER Historian

Taken from Pumice Castle Overlook (formerly “Cottage Rocks” substation) on East Rim Drive. Cloudcap is the highest point at right. |

Introduction Table of Contents |

|

| Circuit Roads | |

| Route 7 — Rim Drive | |

| Approach Roads | |

| Route 1 — West Entrance Road | |

| Route 2 — South Entrance Road | |

| Routes 3 & 4 — Munson Valley Road | |

| Route 5 — East Entrance Road | |

| Route 8 — North Entrance Road | |

| Other Roads | |

| Route 6 — Grayback Road | |

| Early Travel to Crater Lake | |

| Fort Klamath — Jacksonville Wagon Road | |

| Design and Construction of Circuit Roads | |

| Building the first Rim Road | |

| The Need for Reconstruction | |

| Designing a new “Rim Drive” | |

| NPS Collaboration with BPR | |

| Road Location | |

| Construction of Rim Drive | |

| Segment 7-A (Rim Village to Diamond Lake Junction) | |

| Segment 7-B (Diamond Lake Junction to Grotto Cove) | |

| Segments 7-C and 7-C1 (Grotto Cove to Kerr Notch) | |

| Segment 7-D (Kerr Notch to Sun Notch) | |

| Segment 7-E (Sun Notch to Park Headquarters) | |

| Other Designed Features along Rim Drive | |

| Trails | |

| Buildings | |

| Signs | |

| Postwar Changes | |

| Segment 7-A (Rim Village to Diamond Lake Junction) | |

| Segment 7-B (Diamond Lake Junction to Grotto Cove) | |

| Segments 7-C and 7-C1 (Grotto Cove to Kerr Notch) | |

| Segment 7-D (Kerr Notch to Sun Notch) | |

| Segment 7-E (Sun Notch to Park Headquarters) | |

| Design and Construction of Approach Roads | |

| The Army Corps of Engineers Road System | |

| Pinnacles Road | |

| Fort Klamath Road | |

| Medford Road | |

| Other Approaches | |

| NPS and BPR Collaboration on Approach Roads | |

| Route 1 (West Entrance to Annie Spring) | |

| Route 2 (South Entrance to Annie Spring) | |

| Routes 3 and 4 (Annie Spring to Rim Village) | |

| Route 5 (East Entrance to Kerr Notch) | |

| Route 8 (North Entrance to Diamond Lake Junction) | |

| Construction and Use of Other Roads | |

| Secondary Roads | |

| Route 6 (Lost Creek to Vidae Falls) | |

| Routes 25-49 (fire roads) | |

| Service Roads | |

| Rim Village | |

| Park Headquarters | |

| Annie Spring vicinity | |

| Outlying Areas | |

| Conclusion | |

| Bibliography | |

| Historic American Engineering Record Addendum to Crater Lake National Park Roads HAER No. OR-107 | |

Introduction

Located in south central Oregon, Crater Lake National Park embraces a portion of the Cascade Range. The park’s main feature, Crater Lake, is the deepest volcanic lake in the world. Framed by jagged, steep-walled cliffs of a caldera produced by the climactic eruption and collapse of Mount Mazama approximately 7,700 years ago, Crater Lake is renowned for both its clarity and intense blue color. The rim rises anywhere from 500′ to almost 2,000′ above the lake’s surface, creating a spectacular visual effect.

Crater Lake National Park was established in 1902 and has been expanded twice from the original 156,902 acres reserved for the “protection and preservation of the game, fish, timber, and all other natural objects therein.” It currently encompasses 183,224 acres and ranges from the summit of Mount Scott at 8,929′ above sea level to a point on the park’s southwest corner where the elevation is 3,980′. About 80 percent of the park area is formally recommended as wilderness, though one legislative proposal submitted in 1994 supported wilderness designation for 97 percent. The latter includes all but a small buffer around the developed areas and roads currently in use during the summer season.

More than three-quarters of the total number of park visitors come during the four summer months (June, July, August, and September). Annual totals reached a plateau of a half million in the early 1960s and have remained around that figure ever since, though these numbers can fluctuate as much as 20 percent from one year to the next. A majority of summer visitors make their first trip to the park, but the time spent within its boundaries averages just four hours. Visitor services and access are restricted during the winter months, when snow removal operations are necessary to maintain a road connection from the west or south entrances to an observation point at Rim Village. Winter weather over this period of eight months thus forces closure of roughly two-thirds of the park’s road system.

Circuit Roads

Route 7 — Rim Drive

Encircling much of the caldera rim is a scenic, two-lane road extending a little more than 29 miles from the main visitor use area at Rim Village to Park Headquarters in Munson Valley. Linking the two developed nodes is an approach road (Route 4) that extends for about 3 miles so motorists can drive a full circuit during much of the summer season. The entire loop is below timberline, but remains above 6,500′ in elevation. Past volcanic activity made for predominately poor soils whose productivity is also limited by drought conditions in summer. Stands of subalpine conifers (mountain hemlock, Shasta red fir, and whitebark pine) appear in varying density and can be interspersed with largely barren pumice fields. The loop avoids repetition by offering different views of Crater Lake from parking areas developed for that purpose and alternating them with glimpses of the hinterland. Rim Drive’s presentation of the lake and surroundings has been successful enough for the American Automobile Association to name it among the ten most beautiful roads in the nation.

Interpretive marker at the Discovery Point parking area. |

Beginning at its junction with the main roadway through Rim Village, where signs notify motorists of the 35 miles per hour speed limit, Rim Drive heads west on elongated curves for just over a mile before the first large parking area is encountered near Discovery Point. Masonry guardrails, whose otherwise monotonous line is punctuated by crenulations at regular intervals, provide a safety barrier at most of the developed viewpoints and in many places along the roadway where there is danger of vehicles falling down steep banks. It is almost 5 miles from the Discovery Point Overlook to the next junction with an approach road, and motorists pass over a summit at 7,350′ in between these points. The parking areas along what is called “West Rim Drive” are more heavily used during the summer months than elsewhere on the circuit, largely because this road segment serves as a through route for visitors who use the north entrance.

Commencing at the junction with the North Entrance Road is the “East Rim Drive,” which extends for 23.18 miles before it terminates at Park Headquarters. Motorists begin by climbing to traverse the back of Llao Rock, going more than 2 miles beyond the road junction for their next glimpse of Crater Lake. Viewpoints along this northern section are not generally crowded, though traffic congestion is often acute in the vicinity of Cleetwood Cove. This is where motorists leave their vehicles, and pedestrians try to cross the roadway so they can access a trail leading to the lakeshore.

Looking south to the North Junction parking area with Hillman Peak in the distance. |

Aside from the Cleetwood Cove vicinity, that portion of East Rim Drive between “North Junction” and the spur road to Cloudcap boasts a greater variety of shoulder and slope treatments than elsewhere on the circuit. Not only are the remnants of the earlier Rim Road better hidden through planting and some regrading, but also some cut slopes in this section were covered with layers of dark soil to reduce scarring that could be seen at a distance. This part of Rim Drive also retains some original paved ditches connected to drop inlets for cross drainage. These features reflect thinking by designers during the late 1930s who believed that the road’s subgrade should not be exposed to spring runoff from snowmelt.

A series of seven “parking overlooks” begin roughly midway between North Junction and Cloudcap. These retain almost all of their stone masonry and a good deal of the planting done in the 1930s to “naturalize” what in essence serves as a foreground to the visual spectacle of Crater Lake. The first overlook is located above Grotto Cove, about halfway around the lake from Rim Village. It, like the other overlooks, features masonry guardrail, stone curbs, and planting islands used as a traffic separation device. The next parking overlook is less than a half mile from Grotto Cove, at Skell Head, and is followed by five more (Cloudcap, Cottage Rocks, Sentinel Point, Reflection Point, and Kerr Notch) over the next 7 miles. Each provides distinctly different views of Crater Lake, while the intervening roadway also allows for impressive vistas that include Mount Scott and the Klamath Marsh.

Visitors catch their last look at the lake from Rim Drive at Kerr Notch, located some 21 miles from where they began their circuit at Rim Village. The remaining stretch of road, however, cuts across the precipitous face of Dutton Ridge before it offers an expansive view of the Klamath Basin from near the road summit. Rim Drive then descends toward Sun Notch, where a short trail goes to another viewpoint where the lake can be seen, before following along the outer edge of Sun Meadow to a parking area in front of Vidae Falls. The falls are a cascade about 100′ high, but motorists pause at a parking area built as part of a large fill that covers the lower part of the cascade. A few visitors take the short access road below the falls to a picnic area, which also contains a trailhead to a cinder cone called Crater Peak.

The remaining 2.5 miles of Rim Drive from Vidae Falls do not allow for motorists to pull over and examine an impressive subalpine forest of large trees, but some stop at the parking area for the Castle Crest Wildflower Garden. There is a profuse display of flowering native plants in this wetland during July and August, made by a short path. Rim Drive terminates less than a half mile from the parking area, at its junction with the Munson Valley Road near Park Headquarters.

Approach Roads

Route 1 — West Entrance Road

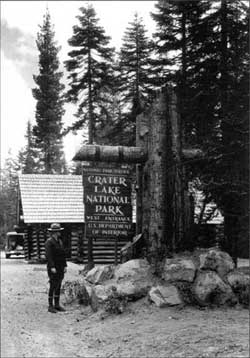

Superintendent Dave Canfield and a new entrance sign, 1936. NPS photo by George Grant. |

Extending from the western boundary of the park to the road junction at Annie Spring, this segment of a state highway leading to Medford and the Rogue Valley is 7.7 miles long. This asphalt road consists of two lanes, each of them measuring 10′ wide, not including the shoulder. Signs notify drivers of the 45 mph speed limit on both ends of this road, but numerous and relatively short curves make it difficult to maintain that speed for any appreciable distance. The slowest section is just over a mile from the Annie Spring junction, in an area misnamed the “corkscrew,” where a reverse curve allows motorists to climb or descend the Cascade Divide.

The West Entrance Road possesses few stopping places or parking areas, even in comparison to other approach routes. With the numerous curves and forested roadside demanding the motorist’s attention, some visitors remain unaware they are in the park until reaching the entrance station located next to the road junction at Annie Spring. The Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) nevertheless crosses the roadway within a mile of the junction and a sign points to an adjacent unsurfaced parking area for trail users. Heading west from the PCT crossing, drivers have virtually nowhere to park alongside the roadway for about 5 miles until a paved pullout delineated with bituminous curb called “Elephant’s Back” is reached. It permits those who stop on either side of the road to see where the canyons created by Castle Creek and Little Castle Creek meet. A half mile to the west is another paved pullout overlooking Castle Creek Canyon that once served as the park’s west entrance before boundary expansion in 1980. The pullout features a vault toilet and information kiosk installed during 2001. Visitors can also stop at the current west entrance a little less than a mile further on, where a sign built in 1998 replicates a rustic log structure erected by the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1935.

The lodgepole pine and Shasta red fir are densely stocked along this route, so most visitors rarely see more than the road prism while traveling. Elephant’s Back furnishes something of an exception, since the canopy is open enough to indicate the expanse of a stream canyon just a short distance beyond the parking area. Some visitors notice the outline of Castle Point, a prominent feature seen as an outline through the “dog hair” stands of lodgepole pine, while driving in either direction a short distance east of Elephant’s Back. From there toward Annie Spring the forest canopy is dense and largely closed, though a portion of Whitehorse Bluff can be seen before climbing the divide on the reverse curve.

Route 2 — South Entrance Road

This portion of Highway 62 links the road junction near Annie Spring with the park’s south boundary, a distance of 10.24 miles. It is an asphalt road consisting of two lanes with shoulders and posted at 45 mph, but elongated curves and greater sight distance in comparison to the West Entrance Road encourage motorists to go consistently faster than the speed limit. There is ample opportunity for visitors to stop and view the stream canyon formed by Annie Creek that cuts through pumice and ash ejected by Mount Mazama during its climactic eruption. Within a mile of the road junction at Annie Spring is the Godfrey Glen Overlook, a paved parking area separated from the canyon’s edge by masonry guardrail. The “glen” is where headwater streams join erosional remnants called “pinnacles,” which occur along the edges of the canyon and can be seen downstream near several other parking areas.

Some separation from the road can be found in any of the three picnic areas on this route. Less than 2 miles south of Godfrey Glen Overlook is the first picnic area, one largely bereft of scenic vistas but located directly across the road from a trailhead leading to Pumice Flat and Union Peak. Two miles further south is a picnic area where Annie Falls can be seen from the southern end of a short loop road. Across the canyon is Crater Peak, a feature easily seen from the highway by looking east. The last picnic area is set amid a forest dominated by ponderosa pine and conifers such as Douglas fir, sugar pine, and white fir. It contains a vault toilet and information kiosk completed in 2002, with only a short walk down slope from these facilities required for visitors to reach Annie Creek.

The last picnic area, one located less than a half mile from the park’s south entrance, is the only place motorists can stop within the so-called “panhandle,” an area transferred from an adjoining national forest in 1932. The size of what amounts to a road corridor, it extends for 2.3 miles and contains large trees that arguably provide the most impressive portal for visitors entering the park. Just over 3 miles from the boundary, however, the ponderosa pine quickly gives way to more monotonous lodgepole pine and some mountain hemlock. These tree species, along with an occasional western white pine, line the roadway toward the Annie Spring junction, though not so oppressive that they keep motorists from the occasional glimpse of features like Crater Peak.

Routes 3 & 4 — Munson Valley Road

From the Annie Spring Junction this road runs north to the junction with Rim Drive at Park Headquarters (Route 3), and then to Rim Village (Route 4). The two-lane asphalt road averages 24′ in surfaced width (including shoulders) and measures 7.06 miles in length. It is posted at 45 miles per hour like both parts of Highway 62 within the park, but there are two long tangents where vehicle speeds often exceed the posted limit. A long spiral curve at grade less than 2 miles from Annie Spring counteracts the tendency to go faster than the speed limit for a short distance, as do a series of shortened curves above Park Headquarters that allow motorists to enter or exit the upper end of Munson Valley.

Route 3 contains the only bridges in the park, starting with a wooden span about 40′ over Annie Creek, and located just a short distance from the spring. It and the bridge over Goodbye Creek, 1 mile to the north, were the first glue-laminated spans in any unit of the National Park System when constructed in 1955 and 1956. The Goodbye Creek Bridge is 70′ high and measures 218′ abutment-to-abutment (see HAER No. OR-107A). Two parking areas on the north side of this bridge form the Goodbye Creek Picnic Area, though the stream separates one set of tables from the other. Both parking areas are delineated with bituminous curb, as are eight roadside pullouts along Route 3.

Although Route 4 is roughly the same length as Route 3, it contains more curves of short radii in having to pass from Munson Valley to Rim Village, and is effectively part of Rim Drive in that it allows motorists to complete a full circuit. Roadside slopes on Route 4 are banked to achieve a rounded appearance, though the vegetation on them is often sparse due to frequent rock fall. Several drop inlets with stone masonry faces are the means of facilitating cross drainage in the steep sections, especially near Munson Springs. The road reaches Munson Ridge (the Cascade Divide) about a half mile beyond the springs and runs largely on contours to Rim Village. One short curve near the village can surprise motorists if they are traveling above the posted speed of 35 mph, not far from where many of them obtain their first glimpse of Crater Lake at the road junction with Rim Drive.

The two parts of the Munson Valley Road provide a dramatically different experience for visitors in terms of what they can see. Large mountain hemlocks and Shasta red fir line the roadside of Route 3, but the absence of understory vegetation provides filtered views into the forest. A parking area separated from the road a short distance uphill from Goodbye Creek allows visitors to leave their cars for a 1 mile walk called the Godfrey Glen Trail, a path that provides them with dramatic views of Annie Creek Canyon not seen from the road. Steep slopes and distant ridgelines are pervasive over most of Route 4, with Castle Crest (a massive ridge below Garfield Peak) dominating the scene above Park Headquarters. As motorists climb toward Rim Village, views of the Klamath Basin and major peaks to the south can be seen.

Route 5 — East Entrance Road

What was once one of the major approach roads in the park is now limited to connecting Kerr Notch on the East Rim Drive with the renowned “pinnacles” on Wheeler Creek. Motorists descend 5.9 miles on a two-lane asphalt road averaging 18′ in surfaced width and then have to turn around at a parking area placed for viewing the pinnacles. Visitors have the opportunity to walk another half mile on a trail from the parking area to the actual east entrance. The through route was discontinued in 1956 after traffic there had fallen to less than 4 percent of all park visitors. Much of the decline stemmed from a relocation of Highway 97 from the Sun Mountain vicinity some distance to the east in 1949. This came after the opening of two major state highways across the Cascades nine years earlier made travel through the park’s north entrance far easier than it had been previously.

The East Entrance Road runs immediately below the East Rim Drive for its first mile, with damage to the pavement evident due to falling rock from Dutton Ridge. This route is at a virtual tangent for the next 2 miles, until it reaches the road junction at Lost Creek Campground. The road closely follows Sand Creek for another mile or so, before veering south to Wheeler Creek and its pinnacles. Partial views of both stream canyons can be obtained in a few places, breaking the monotony imposed by thick stands of lodgepole pine. Once motorists turn around, they have the option of returning to Kerr Notch and rejoining Rim Drive or taking the unpaved “Grayback Road” (Route 6) west to Vidae Falls at Lost Creek Campground.

Route 8 — North Entrance Road

From the Diamond Lake (North) Junction on Rim Drive, the North Entrance Road runs 9.2 miles north to meet state highway 138. It is a two-lane road averaging 24′ wide, not including a shoulder 3′ in width on each side. Much of the road has a higher posted speed (55 miles per hour) than anywhere else in the park, commencing at a point 2.5 miles below the rim. This is due to a relatively straight alignment with no real curvature. Total relief on this road is about 1,000′, half of which is traveled in the first 2 miles below the North Junction.

Open pumice fields and features like Red Cone (7363′), Bald Crater (6478′), and Grouse Hill (7412′) dominate the panorama as visitors descend from the rim and head north. Thick stands of lodgepole pine obscure distant views after the first mile, though the Pacific Crest Trail crosses the highway between Red Cone and Grouse Hill. Visitors enter the Pumice Desert another 2 miles north of the trailhead, and can stop at a paved parking area where the largely barren terrain resulting from the great eruption of Mount Mazama can be better appreciated. The road then disappears into the lodgepole pine forest less than a mile from the parking area on the Pumice Desert, and remains there until the road junction with Highway 138 is reached. There is one short break from the monotony, on a descent toward the entrance station, where part of Mount Thielson (9178′), a jagged peak located on the Umpqua National Forest, can be seen in the distance.

Other Roads

Route 6 — Grayback Road

This one lane secondary road averages just 12′ wide over the 4.4 miles between Lost Creek Campground and the Vidae Falls Picnic Area, with the latter located just a quarter mile below Rim Drive. It is presently unsurfaced, though the remnants of past oil treatment can be seen in several places. Circulation on the Grayback Road is only in one direction (west), with the surface and curvature such that few vehicles can attain speeds greater than 35 miles per hour for even short distances.

A lodgepole pine forest dominating Lost Creek Campground quickly gives way to mountain hemlock and Shasta red fir as motorists cross over Lost Creek and begin climbing Grayback Ridge. They also cross Wheeler Creek (dry during summer) in less than a mile and have to negotiate several curves at grade before reaching points where Sun Creek Canyon, Crater Peak, and much of the upper Klamath Basin can be seen after 2.5 miles of travel. The descent toward Sun Meadow remains almost entirely in the subalpine forest, with limited views of the opening attainable where the road terminates at the picnic area.

Early Travel to Crater Lake

Mount Mazama’s climactic eruption left an indelible impression on the region’s native peoples, some of whom came to Crater Lake for spiritual and ceremonial purposes over the course of many centuries. The first recorded account, however, of reaching the rim came from a failed attempt by a party of would-be miners to locate a “lost” gold mine. They “discovered” what later came to be called Crater Lake on June 12, 1853, but failed to publicize the find from their home base of Jacksonville, the only town of any size in southern Oregon at the time, and one located about 60 miles southwest of the lake. Another group of miners reported seeing Crater Lake in the fall of 1862, though it hardly set off a barrage of publicity in the region’s newspapers.

Fort Klamath — Jacksonville Wagon Road

What made the lake a destination for the comparatively few tourists of the nineteenth century willing to make the trip lasting two weeks or more was a road built to connect Jacksonville with an army outpost established in 1863 at the upper end of the Klamath Basin. One road across the Cascade Range near Mount McLoughlin became a tortuous second choice to a route located in 1865 that followed Annie Creek to a fairly gentle divide, and one leading down from the upper reaches of the Rogue River toward Jacksonville. Once soldiers began building this new road, two hunters hired to supply the company with meat saw Crater Lake and reported it to their commanding officer, Captain Franklin B. Sprague. He wrote to the Jacksonville newspaper about the find as part of publicizing construction of the new road to Fort Klamath. Sprague’s letter focused on the locations of various camps along the road and estimated distances between them for the benefit of teamsters and others bound for the post, but he also described how his men were the first to reach the lakeshore.

A group led by the editor of the Jacksonville newspaper visited Crater Lake in 1869 and gave the lake its name after having used a canvas boat as the means to reach Wizard Island. The resulting publicity spurred subsequent visits by other tourists, though in numbers that rarely exceeded several hundred per season until the mid 1890s. They had access by way of the army’s wagon road within 3 miles of the rim, and many followed another road blazed by the Sutton party up Dutton Creek to the site later known as Rim Village. The upper portion of the Dutton Creek road was one way, and for the last mile, those with wagons faced a situation as late as 1904, where: “One of the older boys or a man would ride to the top or come down from the top to make certain the trail was clear and then fire a signal shot for the wagon to come up or down. Wagons on the way down would tie a log to the back to serve as a drag.”

Establishment of the park in May 1902 brought limited funding for road maintenance, but the first park superintendent, W.F. Arant, soon favored abandoning the road blazed by the Sutton Party and several miles of the wagon road built by the soldiers in 1865. Instead of having to climb this “almost impassable” road up Dutton Creek, Arant proposed veering away from it and then climbing to the drainage divide by means of a “corkscrew” so that visitors could go to the rim by way of Annie Spring and Munson Valley. He began building the new route in 1904 and continued with road construction over the next two seasons, yet the need for more improvements and repair of the wagon road elsewhere in the park were prominently featured in his annual report to the Secretary of the Interior in 1906. Much of the army’s wagon road, in Arant’s words: “has never had any improvement work done upon it; it is washed out, is sliding, crooked, and rough.”

Arant was able to do some additional repair and regrading of the wagon road built in 1865 before his tenure as superintendent ended in 1913, but funding from the Department of the Interior allowed for only a small number of laborers and horse-drawn equipment to be hired each year. As park visitation tripled from 1,400 in 1904 to 4,200 six years later, Arant observed how wagons and automobiles cut into the road surface, making it into a “very fine and deep dust.” He recommended that the road be thoroughly sprinkled with water since the very dusty condition of this and other roads constituted “the most disagreeable feature of traveling in the park.”

Crater Lake from a parking area on the north side of the rim above Steel Bay. |

Design and Construction of Circuit Roads

Only one road ran through Crater Lake National Park when Congress established it on May 22, 1902. The Fort Klamath — Jacksonville wagon road served as an approach route for visitors to the lake, though they still needed to follow a trail marked by blazes for the final 2.5 miles to the rim. A better road on the other side of the Cascade Divide (one going through Munson Valley) reached the site later called Rim Village in 1905, but those desiring to do a circuit around Crater Lake were faced with a cross-country pack trip lasting several days.

The first clamor for a circuit road came from park founder William G. Steel, but only after he started a concession company to provide visitor services at Crater Lake in 1907. Steel told one newspaper that the road’s construction was imminent that September, an announcement that largely stemmed from his optimism about public and private investment at Crater Lake, as fueled by visits from Secretary of the Interior James R. Garfield and railroad magnate Edward H. Harriman, president of the Southern Pacific. Garfield left office after the presidential election of 1908, while Harriman died soon thereafter, but Steel continued his pursuit of funding for roads both to and within the park through the Oregon congressional delegation. His first taste of success in this regard came in June 1910, when Congress appropriated $10,000 for the Army Corps of Engineers to make a survey and provide estimates for future road construction at Crater Lake.

A party of twenty-six men began work to prepare plans, specifications, and estimates for a park road system in August. The engineer in charge came to Crater Lake having studied a topographic map and quickly becoming convinced that a “main highway” or “boulevard” following the rim was feasible, with roads and trails to points of interest radiating from it. As the center of circulation, such a road followed long established precedents, given how circuits for riding and walking had served as the standard way of viewing European parks since the eighteenth century. Prominent landscape designers in the United States during the middle part of the nineteenth century like Andrew Jackson Downing embraced this convention as the desire for public and private parks spread across the Atlantic. It was Downing who provided a hierarchy of service, approach, and circuit roads in his work, and this heavily influenced the design of circulation systems in American national parks. The concept of a circuit road could also be applied at various scales, particularly where this device presented visitors with appealing views and distant prospects. For these reasons surveyors considered a road encircling the lake to be of “first importance,” in that it should follow the “ridges and high points along the crater rim on account of the view.” Approach roads to Crater Lake, by contrast, were to possess little in the way of scenic features.

Building the first Rim Road

Estimates for construction of a complete road system in Crater Lake National Park also reflected the emphasis on a circuit of the rim. Roughly two-thirds of the $627,000 needed to complete the grading for this system in 1911 would go to building the “main highway,” one that the Army Corps of Engineers wanted to locate as “near to the edge of the crater as can be done at as many points as possible.” They figured an average cost of building each mile of road to be $13,000, with the construction estimates based on a roadway 16′ wide shoulder to shoulder and an eventual surfaced width of 12′. This figure did not include paving at another $5,000 per mile, nor the need to build a guard wall as a safety barrier. The engineer in charge of the survey, however, believed that the latter could be hand laid with “dry rubble” without increasing the total estimated cost.

Road building started during the summer of 1913, with work supervised by the Army Corps of Engineers continuing over the next six years. Construction proceeded from the park’s east entrance to Lost Creek, where the Rim Road was to commence. Crews hired on a day labor basis, rather than on contract, started a circuit from there. One group went north toward Kerr Notch and then to the top of Anderson Point in 1913, while another crew worked from a permanent camp established in Munson Valley to reach the rim and continue west. Assistant Engineer George E. Goodwin had immediate charge of the project, which in 1913 also involved a number of refinements to road location indicated by the survey done three years earlier.

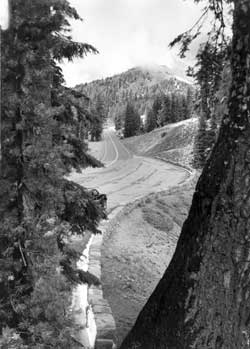

Taken from the West Rim Drive with Watchman in the distance. |

Much of the construction was accomplished through either hand labor or equipment like horse-drawn road plows and graders. Progress in clearing and rough grading could be slowed, however, by the considerable amount of needed excavation by hand with picks and shovels in some places. The likelihood of continuing appropriations from Congress allowed for multi-year commitment by the Army Corps of Engineers at Crater Lake, so Goodwin reported on experiments with various kinds of road surfacing in 1913. This step would follow the grading phase, of course, but the engineers needed to find which type of surfacing could best withstand the climatic conditions and anticipated traffic. They compared various treatments on short sections of road in Munson Valley and found that a combination of an oil bound macadam and bituminous paving held the most promise.

Despite having a small rock crushing plant and a wood fueled steam roller available during the surfacing experiments, lack of funds for surfacing prevented the engineers from completing anything more than a rough graded road around the rim over the next five seasons. Crews completed grading and installation of cross drainage (wood planks in a few places at first, but corrugated metal culverts later predominated) of two segments on the Rim Road in 1914. One connected Lost Creek with the permanent camp in Munson Valley and covered 10 miles, while the other went from Kerr Notch to the summit of Cloudcap, a distance of 4 miles. Having 250 men and fifty teams (many with drag scrapers) during August made a huge difference over 1913, especially since three steam shovels handled most of the excavation.

Appropriations for the work dropped in 1915, so the grading on Rim Road was limited to a section of 3.5 miles between Rim Village and the foot of Watchman. An average force of fifty-five men, six teams, and one steam shovel worked from July to October, with much of the work heavy excavation. The steam shovel handled much of the rockwork, often after drilling and blasting, with finish grading done by hand and teams. Despite the relatively slow progress with grading and installing cross drainage, the engineers reported having settled on a final location for the remaining road construction between the Watchman and Cloudcap.

The heavy winter followed by a cold spring and a labor shortage limited the 1916 season to just 3 miles between Watchman and the Devil’s Backbone, on the highest portion of the western rim. At that point about two-thirds of a projected 35.6 miles of Rim Road had been rough graded, with the engineers commenting that the newest section “provides many advantageous viewpoints of the lake and many beautiful outlooks on the surrounding country.” Grades varied between 2 and 10 percent on the already built road sections, with no curve being less than 50′ in radius and very few being less than 100′. Without surfacing material, however, the Rim Road was bound to become so badly rutted and dusty that automobile travel on it was described as “slow, disagreeable, and in some places dangerous.”

Closing the loop around the rim took two more seasons. Work continued from both ends in 1917, when 100 men and fifteen teams cleared, graded, and installed cross drainage from the Devil’s Backbone and then around Llao Rock to a point above Steel Bay on the northwest side of the lake. A separate contingent of sixty men and ten teams completed a switchback descent from the top of Cloudcap to the Wineglass, where a temporary shelter cabin was built. Day labor thus completed the grading of 6 miles despite a continuing labor shortage that put park road projects in competition with haying and harvesting operations in the nearby Klamath Basin.

Virtually all of the $50,000 appropriation for building roads at Crater Lake in 1918 went to the Rim Road, with most of that amount going toward rough grading of the last 6 miles from Steel Bay to Wineglass. Enough work had been completed by the end of September to allow the first vehicles to complete the entire Rim Road circuit. American involvement in World War I made the labor shortage more acute and snow conditions dictated a late start, but double shifts that often had the two steam shovels working sixteen hours a day allowed the engineers to close the construction camps in early October.

The engineers came back to Crater Lake in 1919, using the unexpended balance from allotments made the previous season to do a small amount of grading and repair on the Rim Road before transferring all property, materials, and supplies to the National Park Service in July. Work had progressed to the point where NPS director Stephen Mather thought it economical for his bureau to assume the responsibility for park roads, even though the engineers saw their project as only 50 percent complete. They pointed to the need for surfacing and paving in every annual report to the Secretary of War since 1913, but no funds for these phases of road construction had been forthcoming, even after a grand total of approximately $417,000 had been expended for equipment, supplies, and labor as of 1919 for grading a system of roads and trails in the park. Well over half that amount was spent on the Rim Road, a project that remained unfinished throughout the following decade.

The Need for Reconstruction

The National Park Service assumed control of the roads in Crater Lake National Park once the engineers departed, but available funding allowed crews to open the circuit each summer by hand shoveling, followed several weeks later by horse drawn equipment that removed rocks from the roadway. By 1923 Park Superintendent C.G. Thomson lamented to NPS director Stephen T. Mather that a rising number of vehicles made maintenance difficult in the absence of surfacing material, since the annual re-grading each fall could not adequately alleviate the problems associated with a rough dirt road. Publicly, however, Thomson extolled the numerous wonders seen from the Rim Road in promoting the park to visitors. According to him, the circuit should be seen as “not a joy ride, but a pilgrimage for the devotees of Nature.” It was where “a hundred views of the magic blue lake and its huge shattered frame” highlighted the “thirty four miles of amazing beauty, three hours of vivid and changeful panorama.” He knew what 200 cars per day over the course of nine weeks each summer could do to such an earth graded road, but Thomson counseled prospective visitors to “approach the experience [of driving around the rim] in a leisurely and appreciative mood, and great will be your reward.”

No matter how reverent the motorist, few considered the Rim Road to be adequately constructed as passenger cars became heavier and faster during the 1920s. Within a decade of the circuit’s “completion” by steam shovel and horse-drawn grading equipment, the narrow roadway made passage of vehicles headed in opposite directions difficult. Even though the average radius of curves “greatly exceeded” 100′, with none being less than 50′, they seemed tight by the highway standards of 1926. Curves needed to be lengthened so drivers could better sustain the posted speed throughout their journey around the rim. Grades varied from 2 to 8 percent (with some stretches of road at 10 percent for short distances), representing another design problem at a time when engineers agreed that a 5 percent grade should be the maximum allowed.

Metamorphosis of the Rim Road into a new circuit of Crater Lake took place as the state highway system and forest roads around the park experienced both steady and dramatic changes spurred by an infusion of federal highway funds expended through the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR). The road system in Oregon grew with the help of funds authorized by the congressional acts of 1916 and 1925 that were aimed at providing the states with aid in building highways. The BPR subsequently supervised contracts to upgrade approach roads to the park, such as the Crater Lake Highway (numbered as 62 after 1926), which had been part of the state system beginning in 1917. It also took the lead in the improvement of the federal system of roads, such as U.S. 97 (also known as The Dalles — California Highway) that served as the main north-south corridor through central Oregon, one that ran just east of the park.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, several roads built in the national forests near Crater Lake became part of the state highway system, including one connecting Union Creek with the south shore of Diamond Lake, and then over to U.S. 97. The most profound effect on the park visitation from building new roads, however, came in 1940. Realignment of U.S. 97 away from Sun Mountain and Fort Klamath dramatically reduced visitor traffic through the east entrance, but opening the Willamette Highway (numbered 58) from the north allowed park visitors to save about two hours over what had been the quickest route from Eugene. Previous work to provide a passable road through the park (much of it involved upgrading the Diamond Lake Auto Trail into the North Entrance Road) to a new “north entrance,” in concert with the effort to connect Diamond Lake with U.S. 97 played an important part in the park’s visitation reaching the unprecedented figure of 252,000 that year. At that point the western portion of the Rim Drive began to serve as both through route and a portion of the circuit road around Crater Lake.

Designing a new “Rim Drive”

On the most basic, functional level, there are several main reasons as to why the NPS and BPR undertook reconstruction of the Rim Road. The reasons addressed ameliorating a narrow, rough, dusty road with sharp curves and steep grades. Significant increases in visitation during the 1920s brought more traffic to the park, though at least one observer noticed that the existing road was so difficult to traverse that only a small proportion of motorists attempted to go around the lake.

View to the north of Wizard Island Overlook, with clouds obscuring the top of Watchman. |

The NPS wanted the new Rim Drive to be a more pleasant visitor experience, but wanted to avoid creating a super-highway on which motorists “would speed around the lake and pass by scenes of beauty in their rush to make the lake circuit.” BPR engineers thereby aimed for a constant average design speed of 35 miles per hour that would avoid gear-shifting on ascent or braking on descent. Instead of the switchbacks and short radial curves evident in places along the old road, designers preferred curvilinear alignment that allowed vehicles to maintain the design speed despite curves and changes in grade. These alignments allowed for constantly changing views by making use of continuous (also called reversing) curves instead of long straight sections (tangents), and eliminated the need for cuts and fills that would be both unsightly and expensive.

Engineers who located the first Rim Road attempted to provide viewpoints of the lake in as many places as possible. The location diminished the interest inherent in being routed away from the lake in some sections, as well as the excitement experienced by visitors in reaching certain viewpoints by trail. The road also created some scarring evident from a few places on the rim since the Army Corps of Engineers had virtually no funding to address landscape concerns, even if such expertise had been available. Designers of Rim Drive aimed for visual unity in reconstructing the road, which included removing it from what visitors saw from the main focal points, or vistas. Unity encompassed the consolidation of park facilities and integrating trail location and design with that of the road.

Another rationale behind reconstructing the Rim Road lay in providing an intended, rather than incidental, link between a road circuit presenting central features and its interpretation to visitors. John C. Merriam, who probably served as the leading figure in creating a formalized interpretive program at Crater Lake, remained adamant that the road primarily serve the purpose of “showing the great features” of the lake and its caldera. He thus decried any attempt to make it a link in a larger through route connecting various points and thought it best to avoid allowing any part of the Rim Road to become a segment of the park’s approach roads. The circuit was instead be part of a plan aimed at presenting features of the region “determined by experts to be of outstanding importance.” Merriam thought that Crater Lake offered “one of the greatest opportunities for teaching fundamental understanding of Nature.”

With Crater Lake showing “the most extreme elements of beauty and power in contrast,” the plan included the development of “stations” where certain views helped visitors appreciate “elements derived from the geological story of Crater Lake and those arising from elements of pictorial beauty.” Merriam cautioned, however, that the “hand of the schoolmaster” not be overly evident at these particular places. The most overt attempt to educate visitors would instead be made at the Sinnott Memorial in Rim Village, a place Merriam referred to as “Observation Station No. 1.” He saw it as the “main project,” though “minor projects” of building the road, some trails, as well as additional observation stations had to be closely coordinated with developing the Sinnott Memorial for visitor orientation.

Where interpretation had formerly been incidental to the experience of traveling Rim Road during the 1920s, the slow metamorphosis of reconstruction was intended to bring this function to visitors in a more concrete way. Each of the seven observation stations built as part of Rim Drive were intended to serve as stops on the naturalist-led caravan that traversed the road in a clockwise fashion, from Rim Village to Sun Notch. All were chosen for their part in displaying a different aspect of the lake’s beauty. Spaced proportionately around the lake, designers intended to each have hard-surfaced parking for a minimum of fifty cars.

Plans for each observation station were to match the “unique beauty of the lake itself,” since Merriam thought the lake represented “a supreme opportunity to teach the significance of beauty through offering to the visitors the experience of beauty.” The points chosen by Merriam and his associates on the western side of the rim were accessible by trail so that the road would not come near enough to the station to create “a disturbing element to one who wishes to observe the lake in quiet.” This was something of a contrast with the four stations located on the northern or eastern side of the lake, which became part of the planning and design of the road. NPS landscape architect Francis G. Lange designated three of the four stations (Skell Head, Cloud Cap, and Kerr Notch) as “parking overlooks.”

Merriam wanted a leaflet describing the stations of Rim Drive to be available at the Sinnott Memorial, in conjunction with adequate signs at each station. These stops might also include an inconspicuous holder for literature describing the station for those who did not visit Rim Village first. As a designer, Lange supplied a more detailed vision for the stations adjoining the road. They should contain, in his words,

“a small promontory circulation point with the necessary stone guard rail (log, if found more suitable) and an interestingly treated sign distinguishing the point in question, as well as denoting any other unusual features. It is also suggested that a suitable mounted binocular glass be set up at each point where found desirable, being mounted on an appropriate stone base.”

For those stations accessible by trail, Lange recommended “stone steps if necessary, then a small promontory platform, some treatment of guard rail, possibly a sign and then a binocular mounted on a stone base.”

Beneath the observation stations in a hierarchy of developed viewpoints along Rim Drive lay the substations, numbering thirteen in 1934, but increased (at least in plans) to seventeen a year later. Substations shared many similarities with the observation stations in that they were chosen for aesthetic or educational reasons, but differed in that they did not function as stops on the caravan trip, nor were all of them formally developed with paved parking areas, signs, or masonry guard rail. Unlike the stations, they sometimes highlighted features situated away from Crater Lake and often focused on specific geological features.

Developed pull outs or “parking areas” served as the next level below the substations in the hierarchy. Although not chosen at random, these stopping points lacked the aesthetic values attributed to the observation stations and substations. Lange commented in 1938 about an effort to restrict the number of such points. Where “an interesting view of the Lake can be obtained,” he wrote, an effort “has been made to provide accommodations.” He also noted in the same report that where “excellent” views of the hinterland existed, several small parking areas were provided.

Preserving the primitive “picture” of Crater Lake received greater emphasis from the engineers and landscape architects as they planned the reconstruction of Rim Road than the interpretation of beauty and geological features. Merriam stressed Crater Lake and its rim was one of the three most beautiful places in the world and that every effort should be made to keep the road from imposing on views of Crater Lake or the surrounding region. Landscape architect Merel Sager described how the greatest damage to park landscapes came from the construction of roads and urged that an “intelligent and comprehensive program of roadside development” could better fit these roads into their surroundings. This meant attention had to be paid to the road as seen in the landscape and the landscape as seen from the road.

Rim Drive followed the old Rim Road wherever possible to minimize impact. Landscape architects and the foremen under contract also paid special attention to planting the noticeable cuts in new sections and trying to disguise (or “obliterate”) abandoned stretches of old road when funding allowed. Contract provisions called for protecting all trees not within the clearing limits (or “right of way”), placing dark soil and trees on conspicuous cuts and covering fills to diminish the ragged appearance of large rocks. Another dimension to the work involved “bank sloping,” where flattening and rounding was aimed at stabilizing cut and fill slopes to permit establishment of vegetation, while warping aided the transition between the bank and roadway. All of these measures reflected the standard practice of using landscape treatments to contribute to the utility, simplicity, economy, and safety of scenic highways built primarily for the enjoyment of motorists. The national parks received special attention in this regard, partly because the NPS pioneered many of the standardized landscape treatments in road design.

NPS Collaboration with BPR

The NPS gained a measure of control over its need to continually upgrade park roads in the face of increased vehicle speeds and a massive increase in automobile ownership with passage of legislation in 1924 authorizing annual appropriations specifically for this purpose. After working to solidify a working relationship with BPR over the next year or so, NPS director Stephen T. Mather signed an inter-bureau agreement on January 18, 1926. Under its terms, the NPS and BPR were to use “every effort to harmonize the standards of construction” they employed with those of the Federal Aid Highway system located outside the parks, while at the same time securing the “best modern practice” in locating, designing, constructing, and improving park roads. The inter-bureau agreement stipulated that the NPS reimburse BPR for overhead expenses from the annual appropriations for park roads. This included various levels of investigation and survey, the preparation of bid documents (derived from the plans, specifications, and estimates, known as PS&E), as well as salaries for engineers to supervise and inspect contracted work.

Once initiated, projects followed a familiar sequence that began with road location. After reconnaissance, engineers did a preliminary survey (or P-line) of the road location to obtain topography for representative cross sections. The P-line allowed for curvature and connecting tangents to be placed by “projection” back in the office, a step resulting in the semi-final location (or L-line). Staking in the field, or final location, necessitated the establishment of benchmarks on the ground, as well as any adjustments to grade or positioning of cross-drainage. All stages of road location were subject to NPS approval, with most of the changes provided by landscape architects.

The process of road design along Rim Drive was shared between the BPR and NPS. At a landscape scale, BPR designed three basic elements of the road: horizontal alignment, vertical alignment, and cross-section. The design of curves and tangents in a planar relationship is horizontal alignment, with preference given to use of spiral transition curves instead of tangents throughout most of the circuit. These made for a sympathetic alignment in relation to the park landscape, but also brought average speed and design speed closer together for the purposes of safety. Vertical alignment or “profile” is how the located line in plan view fits the topography in three dimensions, especially in reference to grade, sight distance, and cross drainage. The banking or “superelevation” of curves represented one particularly significant part of vertical alignment, since adequate sight distance in relation to the design speed needed to be maintained, particularly where a combination of curvature and grade occurred. The third element, cross-section, is a framework in which to place individual features and their relationship to each other. Features such as road width, crown, surface treatment, and slope were usually depicted through drawings of typical sections.

At the scale of individual features, the NPS worked to provide the BPR with standard guidance for the design of road margins (shoulder, ditch, bank sloping), drainage structures (culvert headwalls and masonry “spillways”), and safety barriers (masonry and log guardrails) along Rim Drive. As the lead NPS landscape architect for much of the project, Francis Lange produced planting plans in conjunction with a number of site plans for areas along the road corridor that needed individualized treatment beyond the standard measures described in the contract specifications.

Scott Bluffs parking area with Mount Scott in the distance. |

Road construction consisted of three types of contracts beginning with the grading phase. There were numerous items on which contractors bid on the basis of unit prices for each. BPR engineers, in consultation with NPS engineers and landscape architects, provided estimates for the items, starting with clearing vegetation from the roadbed. Removing stumps and other obstacles to rough grading through blasting or burning constituted a separate item called grubbing. The subsequent rough grading with heavy machinery began with excavation, usually divided into separate bid items called “unclassified” and “Class B,” with the latter often specified by the NPS to avoid damage to natural features. Rough grading also included items such as moving excavated material based on estimated volumes needed for cuts and fills, placement of concrete or metal culverts as cross-drainage, as well as the flattening of slopes at prescribed ratios to control erosion. Completing the earth-graded road involved several items under the heading of “finish grading.” This step included fine grading of the sub-base and shoulders, as well as bank sloping. Depending on how much funding was available, subcontractors handled the stone masonry for culvert headwalls, guardrails, and retaining walls at this stage. Other subcontracted items under the heading of finish grading included old road obliteration and special planting once bank sloping had been accomplished.

With the grading phase completed, a separate contract for preliminary surfacing could be let. This next phase of road construction involved laying a base course of crushed rock on the roadway, followed by a top course of finer material to provide a definite thickness and protection for the earthen road underneath. This type of contract might include items, usually subcontracted, such as building masonry structures like guardrails (often on fills created during rough grading that had to settle over the winter) or special landscaping provisions to be completed as part of executing site plans or working drawings provided by the NPS.

Bituminous surfacing, or paving with asphalt, was done through another contract. This phase of road construction involved laying aggregate (crushed stone and sand) along a specified width of roadway as a base, followed by placing a bituminous “mat” as binder. The thin surfacing of bitumens known as a “seal coat” served as the final step. Completion of the paving contract generally signified the end of BPR involvement with construction. Road maintenance and post construction items thus became NPS responsibility.

Reconstructing 3 miles of approach road between Park Headquarters and Rim Village set the NPS/BPR collaboration in motion at Crater Lake. With the location survey completed several months prior to formal approval of the inter-bureau agreement, the grading contract commenced during the summer of 1926. The project reduced the maximum grade (from 10.9 percent to 6.5 percent) of this approach and produced a new roadway 20′ in width. As a precursor to reconstructing the Rim Road, this realignment became known for how visitors obtained their first view of Crater Lake as a spectacular and sudden scenic encounter. Landscape architects with the NPS chose the point of “emergence,” one allowing visitors to enter a new “plaza” developed on the western edge of Rim Village or begin a circuit around the lake.

The initial step in planning for reconstruction of the Rim Road took place once the inter-bureau agreement had been signed. The BPR reconnaissance survey of the park’s road system in 1926 furnished a starting point and allowed Superintendent C.G. Thomson to reference estimated construction costs in a report on his priorities for road and trail projects over the next five years. NPS officials in Washington requested the report in connection with allocating the congressional appropriation for park roads and trails, a separate process from the site development plans of the period that were aimed at facilities for areas like Rim Village.

Rudimentary lists of projects with estimated costs evolved over the next five years into a bound set of drawings by landscape architects showing the proposed site development in the context of projected park-wide circulation. Formal adoption of these “master plans” by the NPS came as appropriations for park development steadily increased, but these documents remained apart from planning for the location and design of roads. BPR accomplished these tasks through its usual process prior to letting contracts for road construction, subject to NPS approval. Master plans contained some information about Rim Drive and other road projects, but only as context for what the NPS landscape architects hoped to accomplish in a “minor developed area” such as the Diamond Lake (North) Junction or at the “parking overlooks” like Kerr Notch, Skell Head, or Cloud Cap.

Road Location

The idea of better positioning the park for through travel in reference to the location of U.S. 97 drove Superintendent Thomson’s priorities in his report about possible road and trail projects in 1926. A rerouted East Entrance Road received top choice for the time being, but Thomson wanted the west Rim Road improved “as soon as appropriations would permit” in order to better “take care of travel from Crater Lake to Diamond Lake.” He reasoned that this section received more use than any other on the Rim Road, thereby meriting consideration when more money became available, especially since a new location near the Watchman might help get the entire circuit open earlier in the season. Given the park’s short season, Thomson emphasized the importance of the Rim Road to the visitor experience by describing the circuit as “easily one third of the value of our Park and until it is fully open, thousands of people are denied” what he called “their greatest reaction.”

The BPR reconnaissance survey not only allowed Thomson to reference the construction estimates in his priorities, but also allowed him to comment on proposed road locations. It designated the Rim Road as Route 7 in the park and divided the circuit into five segments, labeling them as A, B, C, D, and E. Thomson took an immediate dislike to what BPR proposed as 7-E, a road segment 4 miles long and running from Sun Notch to Crater Lake Lodge by way of Garfield Peak. In addition to being very expensive, the proposed road location necessitated two tunnels and a “gash across the face” of Garfield Peak, which, as Thomson stated, was “altogether too beautiful to be subjected to the unconscious vandalism of ambitious engineers.”

Oddly enough, given his comment on the location of 7-E, Thomson endorsed what BPR proposed for segment 7-D. He envisioned that “all travel will enter the pinnacles (East) entrance” and then proceed to the rim to enjoy what Thomson thought to be the preeminent view of Crater Lake at Kerr Notch. In spite of the cut required across the face of Dutton Cliff on two sides, he enthused about how vehicles might travel “practically on contours” to Sun Notch. Visitors could thus enjoy a panorama of the Klamath Basin and the “tumbled” Cascade Range.

In urging that segment 7-A be given first priority for fiscal year 1929, Thomson stated that the stretch of road between Rim Village and the Diamond Lake (North) Junction constituted “practically a main stem for us.” It not only carried traffic to and from Diamond Lake, but also was the most traveled section used by visitors who did not go all the way around the rim. He believed construction of this 6.7 mile segment might take only one season, to be followed by the other segments over the next four years. In response, BPR conducted a preliminary location survey as another step toward construction during the summer of 1928. Beginning from Park Headquarters in Munson Valley, they went over Thomson’s preferred line for 7-E to Sun Notch in July and then pushed toward Kerr Notch on the reconnaissance line for 7-D. The location crew left Crater Lake at the end of September, having run a P-line for those two segments as well as the one connecting Rim Village with the Diamond Lake Junction. They did so abruptly, after receiving word from Albright that there would be no funding for road construction at the park in 1929.

The delay may have been fortuitous since Thomson transferred to Yosemite National Park in early 1929 and the new superintendent, E.C. Solinsky, wanted additional study of the P-line and segment 7-A in particular. One of his reasons pertained to a plan for building a new administration building at Rim Village. Solinsky believed that such a structure obviated the need for a ranger station there, so the latter could be located at the Diamond Lake Junction. Since he intended it to serve as an entrance (checking) station, Solinsky recommended postponing the building programmed for 1929 until the location of the junction could be finalized.

Another reason for further study pertained to Merriam’s desire for designing roads and trails “with special reference” to presenting park features and those in the surrounding region “which have been determined by experts to be of outstanding importance.” The Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial supplied a grant for a study of the educational possibilities of the parks in 1928, one administered by a committee headed by Merriam. Most of the field visits associated with the study took place over the next summer, followed by recommendations to congressmen well positioned in the appropriations process. At Crater Lake the study effort translated into money for building the Sinnott Memorial with a special $10,000 appropriation as well as funds to hire a permanent park naturalist and an expanded summer staff of naturalists.

Merriam visited the park in August 1929 and paid special attention to the location of Rim Drive. He then wrote to Albright about the need for someone who understood the park’s geological features to assist with locating segment 7-A. The recommendation brought about an on-site inspection of the P-line in October 1929, beginning at Rim Village and going clockwise on the old road to Kerr Notch. Arthur L. Day, volcanologist at the Carnegie Institution of Washington and head of its Geophysical Laboratory, served as Merriam’s representative. Joining him at the meeting were the district and resident BPR engineers (J.A. Elliott and John R. Sargent, respectively), as well as NPS chief engineer Frank Kittredge, chief NPS landscape architect Thomas Vint, and Solinsky.

The group recommended keeping the road as close to the rim as possible over the first mile from Rim Village, but with additional easy curvature to the first volcanic dike visible at the Discovery Point Overlook. They suggested elimination of a tight radial turn at the foot of the Watchman, and then chose a line that kept the road away from views of Crater Lake until the Watchman Overlook. Kittredge noted how BPR appeared to have “solved” the snow problem around the Watchman, presumably by running a lower line than the one adopted by the old Rim Road.

BPR opted for a low line around Llao Rock, though the group favored a spectacular “ledge route” involving sidehill excavation and a series of “window tunnels” on the lake side to obtain better views and reduce 2 miles of travel in reaching Steel Bay. Everyone came to agreement over leaving the Rock of Ages (Mazama Rock) undisturbed. All of the group members wanted the road to reach the top of Cloudcap, but no one thought of marring the fringe of whitebark pine overlooking the lake. This portion of the circuit required further study, the group advised, especially if it stayed close to the rim. The group endorsed the surveyed line between Cloudcap and Kerr Notch, with the stipulation that visitors should be able to reach the viewpoint for Cottage Rocks (Pumice Castle), as well as the Sentinel Point and Kerr Notch localities.

Although the group did not review the P-line between Kerr Notch and Sun Notch, Kittredge characterized it as requiring heavy blasting to make a roadway across sheer cliffs. He saw no way around blasting, but thought damage could be limited if care was used in preventing material from “flowing” down slopes. Kittredge also mentioned two prospective routes beyond Sun Notch, with a decision needed about whether to bypass Park Headquarters and go to Rim Village by way of Garfield Peak instead. One route that did just that came to be known as the “high line.” The other route, a “low line,” largely utilized the existing road connecting Lost Creek to Vidae Falls.

Andesite boulders quarried at the base of the Watchman during the 1930s became a conspicuous part of designed cultural landscapes at Rim Village, Park Headquarters, and along Rim Drive. |

With segment 7-A scheduled for bid in the fall of 1930, the next phase of location work focused on it. Resident BPR engineer John R. Sargent took charge of the L-line survey for the initial part of Rim Drive after NPS landscape architect Merel Sager found the P-line unsatisfactory in “numerous” places. Sager effected revision of the old line with advice from Merriam, Harold C. Bryant (assistant director of the NPS as head of the branch of research and education in the Washington Office), and Bryant’s deputy, geologist Wallace W. Atwood. Sager and Vint went over the revised line with Sargent in August, with Sager returning in October to meet with Sargent about designating certain places along segment 7-A with Class B excavation. Clearing by NPS crews under BPR supervision commenced shortly thereafter as a way to allow the prospective grading contractor the benefit of a full working season in 1931.

L-line surveys continued over the following summer and proceeded quickly enough over segments 7-B and 7-C for the NPS to pre-advertise bidding on them in November 1931. The location work covered a new road of just over 13 miles, one now routed almost to the base of Mount Scott. This line avoided the 10 to 12 percent grades on the old Rim Road’s ascent of Cloudcap through use of a dead-end spur road to the top. After some discussion, the NPS chose a line having a gentler grade routed away from the rim down to the Cottage Rocks viewpoint, instead of going down the south face of Cloudcap. The portion of segment 7-C between Cloudcap and Kerr Notch then became known as 7-C1 and subsequently divided into two grading contracts, units 1 and 2.

Park Superintendent David Canfield could thus confidently assert by November 1934 that the award of two grading contracts in 7-C1 brought the Rim Drive three-quarters of the way around the caldera. Anticipated construction, Canfield noted, would provide the planned connection with the East Entrance and U.S. 97, leaving only a quarter of the circuit “untouched” except for survey work. Location of that remaining quarter became contentious, beginning with a salvo launched in May 1931 by Park Commissioner William Gladstone Steel. He wanted a road built from the base of Kerr Notch to Crater Lake Lodge inside the caldera at a 4 percent grade, a route to be accompanied by a tunnel leading to the water. Horace Albright, now director of the NPS, dismissed the idea as “chimerical.” Bryant wrote to Steel and attempted to point out that the new road’s alignment was aimed at preventing it from being visible at a distance to those standing on the rim.

In any event, Sager pointed to a pair of big problems associated with any “high line” route proposed for connecting Sun Notch with Rim Village, starting with the outlay needed for obliterating scars on the sides of Garfield Peak. He also called the construction of a tunnel proposed by BPR “inadvisable,” owing to the prevailing rock types on the ridge above Crater Lake Lodge. Albright intended to study the high line in relation to the low line favored by Sager and other landscape architects in July 1931 as part of his stop to attend the dedication of the Sinnott Memorial. The director ran out of time to make a field inspection of segment 7-E on that visit to the park, then deferred a decision on it, finally decideding not to build a road into Sun Notch by the end of June 1933. Albright wrote to Solinsky on his last day as director in August and ordered that a “primitive area,” a roadless tract prohibiting vehicular access, be shown on master plans for the lands north of the old Rim Road between Lost Creek and Park Headquarters.

BPR engineers, and Sargent in particular, did not easily give up on the high line. Sargent persuaded Lange and the new superintendent, David Canfield, to walk the surveyed line of roughly 3 miles between Sun Notch and the lodge in July 1935. Lange went into considerable detail about the many construction and landscape problems posed by going through with the high line project in a memorandum to the NPS office of plans and design in San Francisco. He also pointed to the face of Dutton Cliff in segment 7-D as offering the “outstanding” problem, since the road location through large slides of loose rock would be difficult to camouflage. To put a road into Sun Notch around Dutton Ridge struck him as contrary to the park idea of “preserving those areas which are worthy of protection and keeping out any possible development.” Dutton Ridge in particular seemed to Lange to be a “spectacular creation,” while the primitive area around it gave him the impression that he was the first person to visit. He concluded the memorandum with a plea to keep any road at least several hundred feet below the rim at Sun Notch in the event that the higher line of segment 7-D won out over the low line.

Kittredge and the resident NPS engineer, William E. Robertson, also walked the high line within days of Lange’s field trip. They did so in response to a news article appearing in a Portland paper that came in the wake of Concessionaire Richard W. Price taking his case for the high line to the chamber of commerce in Klamath Falls. The local congressman contacted Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes at roughly the same time, and Ickes then referred the query to NPS director Arno B. Cammerer. Albright’s successor dispatched Associate Director Arthur Demaray to Crater Lake for an on-site inspection of the two road locations, and told Ickes that the matter would receive further consideration upon Demaray’s return to Washington. Kittredge’s assessment of the high line from Sun Notch to Rim Village focused on the impact to Garfield Peak, though he offered the possibility of two one-way roads traversing the cliff face in line with Frederick Law Olmsted’s recommendation for that type of construction “for certain places.”

In his reply to Kittredge, Demaray dismissed the high line location for 7-E due to its impact on Garfield Peak. He told Kittredge that further consideration should be given to the high line in 7-D, one that ran “from Kerr Notch around Dutton Ridge to Sun Meadows, then joining the present road [from Lost Creek] at the Vidae Falls. This amounted to a “combination line,” one that Canfield strongly supported when he asked Cammerer to transfer funds originally programmed for the low line route and instead put them toward building segment 7-D. Lange again warned that such a road would “deface and permanently injure” the cliffs of Dutton Ridge, though he injected some levity into the situation by offering BPR the paraphrase “You take the high line and I’ll take the low line,” sung to the tune of “Loch Lomond.”

Vidae Falls. |

Cammerer went ahead with recommending the “combination line” of a high 7-D and a low 7-E to Ickes on November 16, 1935. The secretary approved it several weeks later and his office issued a press release to that effect. Sargent confidently anticipated the decision by completing the fieldwork for what he called the “final located line” between Kerr Notch and Vidae Falls by late October, so that plans could be completed over the winter. Engineers estimated this stretch of 5.5 miles as the most time consuming portion of Rim Drive to build, so BPR divided it into three units (as 7-D1, 7-D2, and 7-E1) for the purposes of bids on future grading contracts. Sargent also ran a P-line of 4.3 miles for the last segment of Rim Drive, one connecting Vidae Falls with Park Headquarters, in the fall of 1935. His successor, Wendell C. Struble, revised the line over the following summer to eliminate about a mile of road construction, mainly because he and Lange agreed that the new line effectively reduced the scar width of 7-E2 as seen from Crater Lake Lodge.

The problem of how to approach Vidae Falls from Sun Notch and then cross the creek remained since, as Vint pointed out, Sargent’s line came too close to the falls and made any road crossing involving a fill too noticeable. He recommended that the line follow an approach road down to the proposed Sun Creek Campground (a development aimed at the interfluve between Vidae and Sun creeks near the old Rim Road), so that any fill used to span Vidae Creek might then be less obvious. A higher location required a bridge, Vint noted, one preferably built of logs. Canfield questioned the cost in relation to an expected life of fifteen years, while also suggesting some revisions to a design used for the log bridge built over Goodbye Creek (located south of Park Headquarters) in 1929.

Resolution to the Vidae Falls dilemma did not come until January 1938, after Cammerer wrote to Canfield’s successor, Ernest P. Leavitt. Not only did he want the new superintendent’s views on the controversial location of segment 7-D, but also he took that opportunity to express a preference for a bridge at Vidae Falls. Leavitt responded with rather emphatic reasons for why the line from Kerr Notch to Vidae Falls constituted a serious mistake, then gave Cammerer a number of reasons why a fill made better sense than a bridge at the falls. Demaray informed Leavitt in January 1938 that a fill had been approved, largely due to the “depleted condition” of funds for roads and trails during the current fiscal year and the small allotment anticipated for 1939. At this point the associate director regarded any lingering questions over the location of Rim Drive as “closed,” since a contract for grading 7-E2 had been awarded the previous fall.

Wizard Island from the Watchman Overlook. |

Construction of Rim Drive

Segment 7-A (Rim Village to Diamond Lake Junction)

With roughly $250,000 allotted for grading just shy of 6 miles between Rim Village and the Diamond Lake Junction, BPR advertised for bids on May 1, 1931. P.L. Crooks Construction Company of Portland was awarded the contract and began work in June by establishing their camp near the Devil’s Backbone. Work proceeded quickly from Rim Village, with roughly one quarter of the job completed in only three weeks.

The contractor’s workforce of ninety men (increased to 125 by mid-July) soon began to encounter rougher terrain, where blasting and other means were needed to move more than 50,000 cubic yards of rock per mile. Just the first four rock cuts (which averaged 35′ in depth) consumed over half of the estimated 150,000 pounds of powder as needed for the entire job. The remaining seven cuts were not thought to be so difficult, with the exception of one running by the Watchman Overlook that measured over 90′ deep.