Larry Smith Oral History Interview

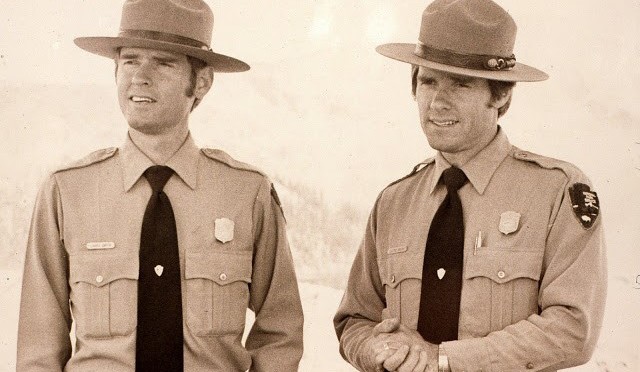

Caption for above photo is unrelated to this Oral Interview: Park visitors aren’t the only ones victimized by the look alikes. At times Larry and Lloyd have swapped name tags and traded work assignments, “but I never tell anyone about that,” deadpans Lloyd. People who look closely find the Smiths are highly similar but not identical. Larry is slightly taller and thinner. Larry parts his hair on right to left; Lloyd from left to right. Confustion exists. Lloyd, who lives in Grants Pass was recently in Jacksonville, Larry’s home city. The principal from Larry’s elementary school saw Lloyd, assumed it was Larry, and began talking about how life at Crater Lake must agree with him because “Larry” had put on some weight and looked much healthier. It works both ways. Lloyd, who is also a teacher, was greeted by some of Larry’s former students wanting to chat. “It took me 10 minutes to convince them who I was,” remembers Lloyd. The confusion began when the Smiths were born in 1940 in Los Angeles. Larry is on the left.

Interviewer: Stephen R. Mark, Crater Lake National Park Historian

Interview Location and Date: Jacksonville, Oregon, February 10, 1989

Transcription: Transcribed by Chris Prout, August 1997

Biographical Summary (from the interview introduction)

Larry Smith can be credited with initiating the first effort to compile the park’s history in an easily digestible format. It started as an extension of a report type that the NPS once called an “important event log,” but continual growth and refinement soon brought about The Smith Brothers’ Chronological History of Crater Lake National Park. This and other topics of mutual interest led to an interview in Jacksonville, at a time when I was still getting oriented with what has transpired at the park over the past four decades.

The interview also marked the beginning of his unflagging assistance which continues to the present. He and his brother Lloyd have contributed to park programs in many ways, most recently as volunteers in the Friends of Crater Lake. Our correspondence since this interview is extensive, and touches on many topics pertaining to history at Crater Lake and the surrounding area. Copies of those letters, along with related source material, are in the park’s history files.

Materials Associated with this interview on file at the Dick Brown library at Crater Lake National Park’s Steel Visitor Center

Taped interview 2110189. File contains newspaper articles, manuscripts, and correspondence. Much of the latter pertains to the Smith Brothers Chronological History of the park which he and his brother Lloyd have compiled or updated to the present. Slide of LBS taken at the time of interview.

To the reader:

Larry Smith can be credited with initiating the first effort to compile the park’s history in an easily digestible format. It started as an extension of a report type that the NPS once called an “important event log,” but continual growth and refinement soon brought about The Smith Brothers’ Chronological History of Crater Lake National Park. This and other topics of mutual interest led to an interview in Jacksonville, at a time when I was still getting oriented with what has transpired at the park over the past four decades.

The interview also marked the beginning of his unflagging assistance which continues to the present. He and his brother Lloyd have contributed to park programs in many ways, most recently as volunteers in the Friends of Crater Lake. Our correspondence since this interview is extensive, and touches on many topics pertaining to history at Crater Lake and the surrounding area. Copies of those letters, along with related source material, are in the park’s history files.

Stephen R. Mark

(Crater Lake National Park Historian)

September 1997

This is an oral history interview with Larry Smith at Jacksonville, Oregon, given on February 10th, 1989. We are going to go through some questions. The first one we’ll start with is…

Where did you grow up and what is your educational background?

I grew up in Phoenix, Oregon, which is real close to Jacksonville. I went all twelve years of school there and then went to Southern Oregon College. After two years there, then I went down to Texas for three years in engineering school. During that whole time, I was working for the Park Service. When I say, we, I was referring to m twin brother because we did everything together. If he turned right, I turned right, and so forth. Everything was owned in common except our shoes, I think. Then I came back to Southern Oregon College and completed another two degrees there in education.

Both in education?

Yes, the first degree was down in Texas at Letourneau College in engineering and then I came back to Southern Oregon College and picked up a B.S in education and an M.S. So I have never strayed very far from home as far as living goes. I hate to admit it, but I was born in California. But, luckily, my dad saw the benefit of moving to Oregon when my brother and I were about six.

So you lived in Oregon continuously since then?

Yeah, except for three seasons down at Texas. It was kind of interesting being in Texas during the civil rights restlessness. I can remember the “colored” signs in the restrooms. We were right there in ’63, just as Kennedy had been elected and Robert Kennedy was starting to create a stir. You could just see a rumble throughout the whole black community. Things were changing real fast. It was kind of fun to be there watching some of this happen. Talking about interesting history, sometimes I saw it actually being made. It was great.

My grandfather and grandmother came out from Montana in ’46, excuse me ’47, to visit. So people always went to Crater Lake. That was just something you did. We moved here in ’46 and my dad was building a house. So by’47, it was pretty well done. We went up to Crater Lake. That’s my first experience of seeing the lake, never realizing it would shape my whole life. And it really did. It’s had a fantastic effect on both my brother and myself.

Was that about the time that you go interested in history as well?

No, it was separate. I just started getting good grades in history. So it was something to pursue. But I always had an interest in finding out why something was named that. Even as a little kid I always wanted to know why was it named or what happened at that spot. So it was more of a curiosity. My grandparents were too old to walk down to the trail, so I remember them sitting up on the rim. My brother and I, and the rest of the relatives, all walked down the trail, the old 1929 trail (1). The thing I remember the most is all the trail cutting that people did. It was a Sunday so there were a lot of tourists there. The rocks [were] falling constantly as people were going up and down because the kids were just allowed to cut. There didn’t seem to be any rule as far as staying on the trail. Nobody seemed to mind. I just remember the rocks rolling down, [and] the kids scrambling. Because the switchbacks were so close to each other, the trail went across slide areas. Every year they just rebuilt it and moved it back into the side of the mountain. That’s why it eventually was closed in ’59 because it was such a problem. When you look at it today, just the first couple of hundred feet of it’s there, but the rest of it is all gone.

It slid away?

It really eroded. There is a little bit at the very bottom, a little stone drywall that’s there, but that’s it. Then my father went to work for Tucker Sno Cat. Old Emmett Tucker was raised just outside of Prospect. He was raised with the idea of heavy snow and how it really affected their life. He had a real liking for Crater Lake. That was a real favorite spot of people in Prospect to take their friends. I remember he was always talking about Crater Lake. He looked like Henry Ford. He had the same outlook on life, basically. He treated his people about the same way. He could be real nice, but he could be real mean.

So he was already fully in production with the Snow Cats?

Yeah, when dad went to work for him in about ’54, ’55.

I know there’s that old story about how Superintendent Solinsky had a design for a Snow Cat that he felt that Tucker had stolen from him.

I haven’t heard that one. Tucker had an inventive type of mind, but he was partially deaf. He started using Model-T’s and started constructing snow machines from them. He started putting skis on them and big chains in the back and skis in the front to steer. Then he moved to California and continued working on designs there. Right after the war, he moved back up here and went into production, I think right about 1947 or 1948. His grandson, who’s president of the company, comes to our church here, Jim Tucker. So we’re still connected with the Tuckers. For the next several years, my contact was mostly during the wintertime, because Mr. Tucker would bring his cats to Crater Lake for testing. He’d try them out in the deep snow up there. I remember the motto was painted on the outside of the building “No road too steep, no snow too deep.”

So they weren’t used by the park?

They [the NPS] used to have a Snow Cat. They bought a small one. You’ll see pictures of it in the files. I don’t know why they never really did much with the Snow Cat. I remember when I started working there in the office in about ’65, I remember when you opened up the key cabinets and there was a label there that said key for Snow Cat. It was still hanging there, I mean the key wasn’t there but the label was. They probably had about a ’50 or ’52 model because it was the old ski front and the pontoons in the back.

We had some pictures donated by Wayne Howe who was there from ’46-’50. Some of his photos are of Snow Cats.

As far as I know, the park only had one. But Tucker was always taking one up there. He was welcome. It’s kind of interesting to see the changes occur because he was always welcome to come anytime he wanted to. He would put on big snow blasts for the public. I remember one year, it was on Mother’s Day of about ’53 or ’54. At the rim there was the big iceberg right out there by the visitor center where they blew it up from the parking lot. It was 35-feet high, I remember. They had steps in there and we’d climbed up and my aunt took a picture of us at the 35-foot level. They had a rope ladder going up with footmarks on it. Every five feet they had numbers. So my brother and I are standing on 35-feet of snow. That “snowberg” wouldn’t melt all summer. It was right there by where the tunnel is now, the winter viewing point.

Yeah, that must have been why we’ve found a drawing for a winter viewing platform in the maintenance files.

The NPS had keep the Miracle Mile open because it was the only easy way of viewing the lake. They always kept the road open to Discovery Point. It was kept open up through probably the middle 70’s. The snowplow operators called it the Miracle Mile because it was a miracle they could keep it open. But the wind blows through there so much that the snow never really gets real deep, despite drifting, so they could pretty well get it cleared out. You could just drive out there during the wintertime.

So a lot of people didn’t try to look at the lake.

No, because you just drive out there and could see it real easily. There were no snow berms at all around Discovery Point.

That must have been why there was a campground relocation study done in ’43 about moving the rim campground to an area near Discovery Point where the drifting isn’t bad and they could keep the campgrounds open longer.

Oh, I see. It would have been terrible to put one out there, but practically it was a good idea. About the third week of July was when they got that thing (campground) opened up on the rim. You remember there was a campground right behind the Headquarters. You can still see the roads below the Superintendent’s house right up around the creek area. That was the preseason-campground. People would come up there and camp. It wasn’t a really developed campground, but they allowed people to camp there while waiting for the snow to melt on top. When that melted out in the last park of July, people’d start camping up at the rim.

That must have been why there was a campground relocation study done in ’43 about moving the rim campground to an area near Discovery Point where the drifting isn’t bad and they could keep the campgrounds open longer.

Oh, I see. It would have been terrible to put one out there, but practically it was a good idea. About the third week of July was when they got that thing (campground) opened up on the rim. You remember there was a campground right behind the Headquarters. You can still see the roads below the Superintendent’s house right up around the creek area. That was the preseason-campground. People would come up there and camp. It wasn’t a really developed campground, but they allowed people to camp there while waiting for the snow to melt on top. When that melted out in the last park of July, people’d start camping up at the rim.

So that area of Steel Circle was allocated for a spring campground?

No, it was right up Munson Creek from where the Administration Building is.

Into the meadow?

Yeah, right in that meadow. You can see the openings where the cars parked and so on. It was never really developed from my understanding.

That’s why the comfort stations are there?

I picked that up from a lady I met. They also had tents set up for employees, which had wooden floors. They’d camp there until they could move to the rim and live up there. Behind the lodge they had a lot of tent houses set up. During the wintertime, they’d stand them up and let the snow just slide off the flooring. They’d drop it back down in the summer and erect the tents. But a lot of people lived up there, a lot of employees. They spent their whole time right on the rim.

My next experiences were basically winter experiences at Crater Lake. We’d go up there and run the Snow Cat around. I remember one year that had 35 feet of snow, Mr. Tucker took out a full page ad in the Mail-Tribune. I remember it cost a sum of 50 dollars. People kept talking about how he took an ad out for 50 dollars. This man must be rich. Then he advertised for anybody who wanted to come up and ride the ‘cats free. They constructed a trailer on four skis. It held about 25 people. It looked like a square school bus. They toward it around. Mr. Tucker did a lot of the driving and he was an absolute madman. Because he wanted to sell his ‘cats, he wanted to show people what they could do with them. My dad still, to this day, talks about when I was in the back and Mr. Tucker ran a ski along the berm where it was dug out for the parking lot. He would drive as close as he could to the edge with the skis of the trailer right behind, loaded down with 25 people. Just gunning the ‘cat wide open. I remember when he wanted to put it back on the truck, they didn’t have a loading ramp. So he just drove it right off the top of a bank. He just smashed it right onto the truck and drove away with it. But he was in it when it went over the edge. He shoved a lot of snow with it, but the man wild up there. We took some pictures and I have them hanging up at the house. They were taken in the sixties and show them racing around up where the campground is, right behind the lodge. And they were encouraged to come up there. It gave something for people to do, especially on weekends. Nobody thought of insurance or liability problems. If you got hurt, that was just the cost of coming up.

Any accidents?

I never remember anybody getting hurt. I went about 10 years without seeing the lake during the summer. I was just during the wintertime. In college we’d take friends up there, so I got to see the lake during the summertime. But it’s interesting how one thing can change your life. You just never know. These little things, an advertisement or something. I remember I was in drafting class at Southern Oregon College, during my second year there. My good friends Henry (Scott) and Raymond (Swingle) were there. Henry was always an explorer and he was reading bulletin boards. He came up rushing over in the middle of class and he said “Hey, they’re giving interview for Crater Lake over at Churchill Hall. Why don’t we go be interviewed?” That was Harry Smith and Pop, who were running the lodge (2). My brother and I thought we had a real in, because our last name was Smith. I don’t remember if Pop was there, but I remember Harry. We went down, went rushing over during a break in the middle of class, not having any ideas of what we were getting ourselves into, just very impulsive, and interview for a job at the lodge. All four of us were rejected. I couldn’t believe it. We were good people and hard workers, as knowledgeable as all the people they had up there. It was a good thing they didn’t hire us, because something much better came along. I saw Harry making notes and said my dad worked for Tucker Snow Cat and I’d been up there many times during the winter. I saw him write that down. That would have been in ’59.

Before they sold out to Peyton and Company.

Henry wouldn’t give up on it and he kept looking into it. We thought Crater Lake was just the lodge. I can see now why people get so confused because I thought that was where you went to work. We didn’t realize there were government jobs up there. So Henry started investigating. The offices were here in Medford. Crater Lake just took a real bite on him. So he went over and talked to Marion Anderson (Personnel director). He found out there was an opening as a tuck driver, so he hired on. Raymond, our other friend went over there and he got hired on as a truck driver. So they said they’d go, and then in June of ’59, Raymond turned the job down. He decided he was going to work for his dad. He calls up Marion and says I’m not going to work for you. They had to go to work the next day. This never happens now-a-days. I don’t think it even happened then. Marion said, “Well, do you happen to know of anybody that would like to have the job?” You’re not supposed to do that, even in ’59. Raymond says, “Well, Lloyd Smith is looking for a job this summer.” I was in the hospital up in Portland, as it turned out. I was having some constructive surgery done, so I wasn’t available. So Marion called Lloyd. He was out milking the cows and the phone was ringing. Lloyd happened to walk in the garage and he could hear it ringing. Marion had let it ring and ring. Again, this is showing you how one little thing can change a whole person’s life. He’s ready to hang up, but Lloyd hears the phone. He rushes in, picks it up, and Marion identifies himself and says would you like to go work at Crater Lake tomorrow. Mother was with me up in Portland. Dad was at work. Lloyd was 18. Do you want to go work at Crater Lake? And he’s standing there and goes. “Well, yes, I’ll go work.” And that’s what started the whole thing. So then I came back in ’60. Tried to get on, couldn’t. But in ’61, I got on in maintenance. Found out how you did it back in those days, you got Congressional appointments.

Referrals.

Yeah, so we decided to play the game. While we were in Texas, we wrote letters to all the congressman and all the senators from Oregon and got on. So I started working on maintenance up there and did that for two years. My brother and I were both there when the old guard was still in charge. Buck Evans was a colorful character. He was Chief Ranger.

He had a long history at Yosemite.

Yeah, 25 years, or something like that.

How long did the referral system last? Did it get phased out by the mid-sixties?

I still remember getting hired in our own right. They didn’t really talk about it [Congressional appointments]. The park didn’t like them. Maybe in ’59, ’60, ’61, there wasn’t a real hard feeling toward it. But I thought, well, if that’s the way to go, that’s the way you get on. We wrote our letters and got hired immediately. So it must have done some good. I’ll never forget I got one letter back from [Wendell] Wyatt. He was an eastern Oregon representative, and he says absolutely not. I don’t even know you, no way am I going to. He did it the way he was supposed to. I mean, that’s the way you should act. But everybody else, we got glowing reports, I guess. You see, you weren’t automatically allowed to be hired again. It was a one shot, and then they’d hire you if they could. They had to open up positions for Congressional appointments (and veterans), and you saw a lot of rich kids. And that was why the feeling was so bad because they were getting these rich snotnose eastern kids who probably enjoyed the experience, but they threw their weight. And so it left a bad taste in peoples’ mouths.

I heard a story about that in Lassen where Lou Hallock threw out six referrals who were not doing the job (3). He wasn’t afraid to take the heat.

Oh, wow. That would take a lot of gumption to do something like that. I remember, in the sixties, they always kept usually one position open somewhere in the park for a referral. The last one, I think, was Chuck Lamb. Everybody just kink of bowed to him because he was a referral. But he was great. And he came back in his own right for years after that.

Even to this day, when I walk up and see that lake for the first time after a period of absence from it, those feelings just come flooding back to me of all the years I’ve seen it. Then I start thinking about what people say. “You mean this is all there is to it? You mean I paid a dollar to see this?” You want to shove them over the edge. It always had a real special feeling because of being associated from when you’re a young child. It’s kind of like a song. The reason you like the song is because you get flooded with memories. A smell; it brings back something out of your childhood. Having been associated with Crater Lake since I was seven, it’s home. I’m approaching Steel’s 49 years of involvement with Crater Lake. But I think that’s why the thing is so special to my brother’s and my heart because it’s going home every time you go up there. With the changes that have occurred over the years, I think that the people that are living there do not have the appreciation. It’s a job jump. They’ll do a decent job. They’ll work at it but they’re basically bureaucrats. They’re trained that way. You notice how man city folk are coming in? My last year was ’85 and it just seemed like there was this prevalent feeling of “What’s there to do? We got to get something to do.” Then the big screen television is bought, the cable system was put in. I think, what a contrast, those people should have lived there in the ‘forties and ‘fifties. Employees were living in those three-room un-insulate buildings. And they were there all winter. And they were happy. Those people enjoyed that. But you see these people stayed ten, fifteen years. It wasn’t something you could say I’m going to move the first chance I get. I’ll work toward retirement.

I heard a story about that in Lassen where Lou Hallock threw out six referrals who were not doing the job (3). He wasn’t afraid to take the heat.

Oh, wow. That would take a lot of gumption to do something like that. I remember, in the sixties, they always kept usually one position open somewhere in the park for a referral. The last one, I think, was Chuck Lamb. Everybody just kink of bowed to him because he was a referral. But he was great. And he came back in his own right for years after that.

Even to this day, when I walk up and see that lake for the first time after a period of absence from it, those feelings just come flooding back to me of all the years I’ve seen it. Then I start thinking about what people say. “You mean this is all there is to it? You mean I paid a dollar to see this?” You want to shove them over the edge. It always had a real special feeling because of being associated from when you’re a young child. It’s kind of like a song. The reason you like the song is because you get flooded with memories. A smell; it brings back something out of your childhood. Having been associated with Crater Lake since I was seven, it’s home. I’m approaching Steel’s 49 years of involvement with Crater Lake. But I think that’s why the thing is so special to my brother’s and my heart because it’s going home every time you go up there. With the changes that have occurred over the years, I think that the people that are living there do not have the appreciation. It’s a job jump. They’ll do a decent job. They’ll work at it but they’re basically bureaucrats. They’re trained that way. You notice how man city folk are coming in? My last year was ’85 and it just seemed like there was this prevalent feeling of “What’s there to do? We got to get something to do.” Then the big screen television is bought, the cable system was put in. I think, what a contrast, those people should have lived there in the ‘forties and ‘fifties. Employees were living in those three-room un-insulate buildings. And they were there all winter. And they were happy. Those people enjoyed that. But you see these people stayed ten, fifteen years. It wasn’t something you could say I’m going to move the first chance I get. I’ll work toward retirement.

How have things changed over the years?

I think probably the biggest thing is I don’t see people out as much. I could be mistaken. Maybe you’ve got a different guard in there, but the last few years I was working there, there [was a lot of] complaining about the place. Benton made, and he is a good superintendent, a statement once “Out of Alaska, this is THE worst place to live, to winter” (4). I suppose it is if you’re used to the city. But other people revel in that kind of thing. And I remember he was trying to get some kind of hazard pay, isolation pay, that you get at Fort Jefferson. He was trying to convince region that the park was qualified as that kind of place. And yet under Buck Evans and those others you see that was normal. You were honored to be able to have a place like that to live. And you made a career out of it. You raised your family right there. Look at Johnny Fulton and his father. He’s (at) Rainier, I think, or Olympic?

Rainier.

He put probably 12 years in the park working part time and then coming on full time. But the Fultons go back to the ‘forties. They and other maintenance employees were all trained in heavy equipment and stuff like that from the war. They moved here in ’46-47 and went to work for the Park Service. They just stayed right in the park. A lot of them built their homes just outside the park. Gourley was never going to leave (5). That’s his home. I think you can get this entrenched feeing, perhaps.

There seems to be a difference between the people who come back year after year after year and people who have civil service status and are looking at other opportunities in the Park system.

Then you have people who came in, like Dan Sholly, who really made a difference in the park. Mayberry, what was his first name, I just about had it, Slim Mayberry. He’s the one that put on the Crater Lake ski races so much. He was Chief Ranger there, but he was always thinking of things to do for the people during the wintertime, outside. He had old engines going and put rope tows in and things like that. Especially in the maintenance area, people really stay a long time.

I think that is still pretty much the case.

Yeah, about half your staff is like that. I remember when I was working there, I hardly ever saw a new person when I was working in maintenance. And you learned from these guys. A lot of my stories that I’ve come up with, the cars over the edge, and stuff like that, at lunch hour you sit around and talk to Guy Hartell and Stub Jones. These old guys were just full of stories and they’d just BS like crazy over lunch. You’d pick up the stories. I was out working with these guys, a little college kid. We respected these man. They were great people. So I think there’s a lot to say about longevity to a certain extent. You get continuity.

I think that in a lot of cases, it depends on the person.

Some people can’t stand that type of life.

And some people love it. They are really able to develop an understanding of a park if they can be there for awhile, rather than the one-to-two year stopover and they’re off to something else.

Seasonal are kind of getting that way. I remember some coming in and saying I’m just going to be here one year, announce it from the beginning and going on to another park the following year. It’s great to have that experience but it’s kind of nice to have depth for people. That was the part I probably enjoyed the most about my job, was being able to answer peoples’ inquiries easily after a lot of studying. We used to have an old saying in the park, “It’s a question only once”. The next time you should be able to answer it very easily. I always kept 3 x 5 cards in my pocket. When somebody’d come up with a question I couldn’t answer, they’d write their name and address on one side and the question on the other and within a week I’d try to have a letter to them.

Not really.

Was this basically your own initiative?

I guess because I was always so curious about things, I wanted to make sure to answer whatever questions visitors had. So many times you go into a park, and I’ve been in probably 150-160 park areas. I always have three or four basic questions I ask. First, to see what level I’m talking to, my little test. Then I look at their uniform to see what kind of person they are and then maybe you can get going on something. But I find the majority of the people working in the parks are very unknowledgeable of their area. I’m just shocked. It just leaves a bittersweet taste in your mouth to know that they’re not even trying.

So it’s more interest rather than lacking the background?

Yes, I think so. I think it’s the interest, especially in the eastern parks. There’s such a lackadaisical attitude, they don’t know anything about the western parks, the seasonal. They could care less. I talked to a little black gal in uniform right in front of the National Visitor Center in Washington D.C. I kink of knew where the White House was generally, but we’d gotten kind of turned around. I walked up to her, and she’s standing there talking to her friends. I said “Is the White House that way?” “I don’t know.” I said, “Well, where is it?” “I don’t know.” We were only about three blocks from the White House and she turned around and went back to talking to her friends. You go to those little information centers all the way down through the Mall. You have all these people in uniforms and they know nothing about anything. I don’t know what they’re there for. Some kind of work program, I guess. But other areas, like Gettysburg, I still think back 12 years ago to two people that we came in contact with there. When I see Gettysburg, I see these two seasonals, a guy and a gal. We heard one in the morning and one in the afternoon. And when they got done, you could smell the smoke of the battles. Most parks it’s so much stone and just so many names carved on those stones, but it’s the people that bring it alive. That’s why I think the Park Service has got to be really careful of keeping the people out in front who are knowledgeable, who really love their job.

It seems like the seasonal application doesn’t seem to address that. It’s really how well you can fill out of form rather than what you got up here.

And don’t sell yourself short, they always tell you. Give yourself a few fives and then you perjure yourself at the end when you sign you name. I think of all the long-term seasonals that I had, like Tom Young, old Tom Young. We had a young Tom Young and an old Tom Young. But old Tom Young had been there close to approaching 20 seasons and Nancy Jarrell, my brother, myself, and so many of the others that came back year after year. Making sure we didn’t get stale – that was important. If you’re aware of it that’s fine. But able to get into a decent conversation with people and you become almost friends.

I found myself in three or four duty stations over a period of two or three days. You’d give an evening program and you’d see a certain family. Then you’re at the visitor center maybe the next day and you meet them or they might be on one of your hikes. Then the third day you’re on the boats and there they are, just by coincidence. You’re old friends by then. You’re about ready to start passing addresses back and forth. And they say, “Oh great,” and you know something about them. They just sit there and get all excited and so on. If I found anyone interesting, I’d bring them into my programs somehow. The first lady ranger at Crater Lake was on my boat trip in about ’48 (6). She lived with Leavitt in the old stone Superintendent’s house. He provided room for her and board, I guess. She was a seasonal. What an interesting person. So I got her on microphone up there and she talked to the visitors. What an interesting talk she gave. When I was working Mazama, I’d always talk to the visitors ahead of time. Try to find somebody I could interview, and just add a little bit of interest. One day I found this guy, and said to myself that this guy’s got to have s story. I made a bee-line for him and tried to find as much information as I could. Sometimes it goes flat. When I’d find somebody playing a musical instrument in the campground, I’d invite him over to play during a program. Things like that. One guy I just couldn’t get to quit after I did. Unfortunately, I didn’t tell him only two songs. You see, it’s kind of interesting, but when do you bring out the cane? One gentleman was Chief Ranger of a National Park in New Zealand. He was a tall, strapping guy, and real muscular. So I brought him up front. I asked him if I could interview him. No problem. My first question to him was “Well, sir, what do you find is different about American national park and New Zealand national parks?” And he looked at me and he says “We don’t have to worry about stupid hats.” He looked like a real ranger’s ranger. It was a great interview with his accent and everything.

You have to work at your job to make it interesting to yourself, too. I remember when I was at the entrance station. I was there for one summer. Of course, that was what everybody worried about. When you got hired, were you going to get the box? When even the Chief Ranger starts calling it the box, you know you’re down at the bottom. When we started working there, it really wasn’t that bad. We just knew we didn’t really want to. I remember after ranger school, Rod Kieser, who was head dispatcher, came in. He was kind of the secretary for Buck Evans. He had the bonding notices to be signed. When he came walking in the room with the bonding notices, I knew somebody was going to be handling money, and the only place you were going to be handling money in those days was the entrance station. We still hadn’t been told our assignments. I remember making myself scarce. I kept moving against the wall. I wanted to move away from him. He walked right past me, didn’t had me a bonding. That meant I wasn’t going to be working the entrance station. I was going to be patrol. Patrol basically “There’s the key. See you in eight hours.” Things are so different now. I remember Gene Shegebee and I walked out. They just said “Drive to the rim.” We were law enforcement officers. We were going to go out and insure the public safety of the park. I knew something about the park because I had worked on maintenance for two years, but Gene was just green. We drove up to the rim trying to get out of the car with the flat hats on. You bang into the wall, going through doorways. You learn how to negotiate after awhile. But I remember that, tripping over our shiny shoes, trying to look neat and clean and everybody feeling a magnet of their first time in the uniform out in public. We were proud, yet we felt like we were sticking out like sore thumbs. And that basically was it. We just patrolled the park for the rest of the summer. Our training was basically the power structure of the park, the power structure of the national organization, a little first aid, place names, and a little history of the park. Ranger School lasted three days. It didn’t amount to much. I hate to ramble, but I keep thinking of rather interesting things.

We can use the questions as sort of a guide.

In the ‘sixties when we still had the old guard, the old guys that just didn’t follow the rules. Buck Evan didn’t follow the rules. And nobody was going to tell him to follow the rules, either. Budgetary-wise I think he did, but when it came to the rest of the stuff, he laughed at the idea of shiny shoes and he’d take his pen and he wouldn’t retract it before he stuck it in his pocket. And he couldn’t always find it. He’d just be talking and he’d be rolling it up and down like that. By the end of the week –he usually wore his shirts all week – it’d just look like a big flower there. But that’s no problem with Buck. He always carried gloves in his back pocket. His shoes were never polished, his shirt was hanging out. He always walked around scratching his head. “Well, guess I better go upstairs and count my money.” He was always counting his money to see if he had enough money for the end of the summer. They didn’t really work on a budget system, I don’t think, because if they started running out of money, they just started laying people off. We knew we had a job until sometimes in the middle of August, but we weren’t guaranteed jobs after that. But if the middle of August came and he still had some money, he’d keep a few people around. If not, you’d all get laid off. It was a funny way of doing things. And he always made sure that you got terminated before your 90 days, because after 90 days, they had to pay you holiday pay (7).

They could just extend you x amount of days?

We had to have 90 days before we got vested. They’d dump you at 89 days to save that three-and-a-half days of pay that they had to give you. When they started getting uniform allowances, he [Buck Evans] always bought guns with it. It never went toward his uniform. Oh, the stories about him are just wonderful. He was the kind of guy you just loved. But then they removed him after he was Chief Ranger nine years. He was finally removed and became a file clerk to finish out his career. They called it a management assistant when he was a file clerk. I saw this grand man who was a legend in Yosemite and how he could fix up broken hips and legs and haul people out mile after mile through snow. This man was incredible, and here he was reduced to filing papers for about two years. He had a little office next to the Superintendent’s office. He’d go around every morning and he’d pick up the mail and deliver it to peoples’ offices. He’d pick up the in basket and dump out the basket. He was just biding time.

To get his high three? (8)

Yes. So it’s interesting what happens to people after awhile. He wouldn’t play by the rules, either, so I guess he deserved part of what he got. Maybe it was his choice. I don’t know. But you saw a lot of people that belonged in the Park Service and other people that didn’t. Management styles of some of the superintendents. Crater Lake was called the elephant grounds, if you know what that expression means. This is where they put people out to pasture, Superintendents, I mean. Brown, was an example. I never did know Williams (9).

He was just before.

Yeager was old, my was he old (10). He had a ’61 Plymouth with the big wings on it, I remember. Every morning he’d come down to the maintenance building (11). He’d drive up in his big green Plymouth with the wide wings on it and get out and they’d plan the day and what people were to do. But he was kind of a grumpy man. People didn’t get to know him, little guy. Everybody was fascinated by his first name, Ward. I guess “Leave it to Beaver” had been on by then, but I had never watched an episode of it. Richard Nelson was old (12).

Didn’t he die of a heart attack?

Stroke. He collapsed right there in the Administration Building. He was really well liked. He had a nice family. His family was younger. He was older. He was a portly man, very pleasant, treated everybody nice. He had a kind voice, that people just liked to hear. He had a lot of respect.

Right now we’re discussing the Superintendence of Einar Johnson (13).

The story goes that the Regional Director came into the park, into the Administration Building one day, and said, “This place looks old. Do something about it.” So the first thing he (Einar Johnson) did was put plastic on those little benches at headquarters (14). How many are still surviving? There were still four of them the last I saw, but are there still some in the lobby?

The rustic benches? There might be three that I know of.

There were still three there and one had gotten moved up when they put the window in that large room to the left of the fireplace. They were designed to sit in those four corners and that corner was taken up by the dispatch window (15). The idea was that we could run the radio and still take care of the visitors, and handle business. So they put the bench into the old room that was the school house back there (16).

So that’s where the school was.

Yes, there was a double hallway entry. On the left was the teacher’s office for small group instruction and the big room where the safe was, was for large instruction.

Apparently at one point, they’d gotten moved up to the Sinnott Memorial.

One was moved up there.

Rotting away…That got moved real fast.

I remember an old guy came in sometime in the ‘sixties and he said “They’re still here!” He said, “I carved those.” I was dumb. It was before I was doing a lot of trying to tag people. So I never got a name on who it was that carved them.

The design was Francis Lange’s (17), but as to who carved them….

You see that one at the rim survived the plastic era because it still had the full-grain horsehide, or leather.

The leather that they brought in from San Francisco.

Oh, you know the history on that. Well, the story is that Einar covered the top of them.

There was one that still has a vinyl top to it.

That old pinkish-orange, that was Einar’s legacy.

So, that’s where that came from. It’s in the museum right now.

The bench?

Yes, I now have the table in my office.

Oh, you do? His wife as the story goes, was the one who went down to Klamath Falls and picked out the plastic. And they put it over the top of them. It looks very ‘sixties. It was the color that Plymouths were coming in. That orange plum. It was a sick color. Everything was painted that color, it seemed like. So then he hired a couple of old painters. I loved those two old guys out of Medford. They did a lot of painting for the park during this era. And they were always ridiculing the park. They were nice people, but I was working on the radio in dispatch and they were in there painting over all the dark molding. He says, “This is stupid. You’re not going to keep the paint on there.” They used what they call a liquid sanding, that’s supposed to take the varnish. It made the varnish rough so the paint would hook to it. And of course, it started coming off immediately every time he’d touch it. I just detested it. It looked ridiculous from the day that they put it on. But that’s what Einar wanted. He took out the big old chandelier from of the lobby of the Administration Building and put in fluorescent lights. He was always doing stuff like that. He didn’t have any appreciation. That’s when they butchered so many of the cabins and tried to modernize them to a certain extent. They pulled out all the old fixtures and just dumped stuff.

Did you ever meet any of the regional directors during this time?

Yes. They’d come sweeping, but they didn’t pay much attention to the people running dispatch. I saw a lot of activity coming through the park because I’d usually work two days and then three nights, evening shifts. So I was there during the day sometimes a lot. Some years, I’d have five days a week. I was there during the day. So I got to see a lot of the park activity. People came to me because I always knew what was going on. The superintendent’s office was usually open so you could cock an ear and listen to what was going on in there. I tried to keep track of things just to satisfy my curiosity. That was during the time that I found out about the superintendent’s special hiding place for his booze. Of course that disappeared during the remodel, but it was right there by dispatch down that little hallway (18). I think they’ve kept the clothes closet in that stairway there, but I think it’s kind of open. I haven’t been in the building that much since it was remodeled. When I was at the park on weekends, it was closed.

That may have been built originally for Canfield.

Yeah, for his drunkenness. You came after the remodel didn’t you?

Yes.

So, you never did see that thing. It was beautiful. It was well done. It was right in that clapboard-type wall board that they used. He just held it and it just slid right up. There was an old bottle back in there. He just kept it there. We kept things hidden there that we didn’t want other people to find, a few of us that knew about it.

The one in House 19 is fun to show people.

Was it hidden?

Yes, but it’s right in the dining room.

The panel moves or something?

It is in a bureau and you trip a little lever under the first drawer and up pops the bottle.

Oh, really. I didn’t know about that.

Einar was kind of a sixties superintendent. Richard Sims was the strangest superintendent of all (19). There was nothing on his desk. He was such an unusual superintendent. Soft spoken. He’d come over from Oregon Caves.

So Sims and then Betts?

Sims would bring people into his office. He’d have all day to talk to you. He’d gather up kids and talk. And his wife was the Secretary-Treasurer of the NHA. She did a good job and had a desk right in the Ranger Office. From where the Superintendent’s office was, you’d walk through to where the library was, and that would be her desk. He’d always come in about twenty of five and stand there, waiting for her to finish up the books so he could go home. He always gave her a ride from Steel Circle over to the Administration Building and back again. Once thing they did do was spend a lot of time at the evening programs. She was always with him and rode in the government car. They were together a lot. Last I heard he was in the regional office.

Was that unusual for Superintendents to go to evening programs?

Yes. Mr. Benton announced that he would never be seen at an evening program. He said that publicly. I heard him during one of my training schools. He said that was not his place, I guess, to go to evening programs.

I know that some of the regional office people went to evening programs last summer when they were up for the operations evaluation (20). I didn’t know whether that was unusual or not.

Rouse went to evening programs a lot (21). But his wife didn’t live in the park that much. She would come and go. They had a house in Corvallis. She seemed to enjoy it there a little bit more than at Crater Lake. Well, you couldn’t have dogs when they arrived. They had a poodle that just had to live at the house, so he changed the rule for the first time since the park had been established, so that employees could have animals.

That was Rouse?

Yes. Rouse changed it. And that was to placate his wife. And then she ended up not living in the park, at least not very much. He was a very lonely man. Can I talk a little more about Sims?

Sure.

Had that water crisis occurred under any other superintendent, it [the problem] probably wouldn’t have gone to the extents that it had. He just was not in control of anything, he just wrung his hands. This thing kept coming down on him and he was in the wrong place at the wrong time. During the hearings in Medford, [Senator Mark] Hatfield came to find out really whose fault it. “It wasn’t me officer, the other one was driving.” Everyone was blaming Peyton and Peyton was blaming Sims for not taking action. Well, every time Sims tried to take action, Peyton just ran over the top of him because Sims was so mousy. Have you ever watched Mark Hatfield in operation? He is wonderful, like a double-barrel shotgun going off. You watched how this man commands attention. And he was there from nine in the morning until about eleven o’clock that night in this hearing, and parading witness after witness through this. It seemed like it was in the afternoon in the Medford City Hall. Sims finally came to the witness stand. It was something to watch. Hatfield absolutely undressed that man in public until he just left a pile of protoplasm.

I don’t think he had any preconceived ideas about Sims. I’m sure he’d heard about him. But he said, “Where’d you come from?” “Oregon Caves.” “What did you do over there?” “Blah, blah, blah.” “Okay, so you came to Crater Lake. What was your training?” Sims said, “I didn’t get any.” He says, “Well, was the superintendent there to show you around?” He say, “No, the superintendency had been vacant for several mouths when I got here. I just came and took over.” And then Hatfield just lit into him. He say, “You mean to tell me that nobody trained you for that job?” “No.” So then he got into the “Well, how come you didn’t close the park down when people started getting sick?” “Well, I didn’t think it was this bad.” Sure, you see in hindsight that for Hatfield it was really easy to look at this thing. But Sims said “I didn’t think anybody was that sick.” And then Hatfield exploded. He says, “My God, man, did you want somebody to die first before you took action?” But when he left the witness stand, poor Mr. Sims was just devastated. He was absolutely stripped of anything and he was out of Crater Lake in a matter of weeks, along with the Chief Ranger (22).

Vic Affolter said that there was a lot of dissention between permanents and seasonal.

I was there answering the telephones. I was there at dispatch center when all these newsmen were calling. So I saw all this happening. When the park was closed and nobody was supposed to go in, Sims would sometimes go down to the gate and pick people up and show them around the park (23). Newsmen, cameramen and people like that. He did try to help people out. I guess he felt bad with the park being closed and so he’d do things on his own. Sims went out of there just absolutely stripped of his career, everything. It was horrible. As for the Chief Ranger they gave him an opening, “Okay, you want to go there.” He’d turn them down. Finally, Cape Hatteras came open and they offered it to him and he said no. They said you have no choice, and he was jerked out of the park with his four or five kids. I think he was made a district ranger at Cape Hatteras. The following year we went by and visited them and spent the nigh.

I think it was a period the guys up in the park were trained in the field. That was before the Park Service really had good training programs for people that were coming up. You had a kind of limbo, and these guys really didn’t know. They were bureaucrats and that was about all they were.

And then Betts Who cam ever forget Frank Betts? (24) And then Sholly what a combination (25). Those guys were so professional. Betts and Sholly would get into it. I was telling you a little bit on the telephone about that. They’d scream and yell. You’d hear them in there just going around and around. Nobody was going to give up on this. But at the end they were friends. And I’d see Sholly tearing into Frank. Frank was not going to get away with this. “What does that man think?” They had their cat fights, but it was wonderful. The park just soared under these two guys. The euphoria with the seasonal and everybody working up there. These men could walk on water. They couldn’t do anything wrong. It was a wonderful feeling.

I was going to go back and finish that story on Einar Johnson. I was working on my Crater Lake history a lot during that time. I’d have a few spare minutes toward midnight and I’d typing, looking things up, and so on. I had it laying on the counter where you talked to people. I was going through doing something and Einar picked it up and started flipping through it. In it, I had the date for the loss of the dark woodwork in the building. It said, as I remember, “The dark woodwork is painted over after gracing the building for x amount of years.” I saw Einar’s eye stop at that. He didn’t say a word. He looked up and pulled out his pen and scratch, scratch, put his pen in his pocket, and walked off. So I left it out of that particular edition, but I put it back in there again after he left. That was censorship, but I had put a dig in there.

I had not met Betts when he and Sholly came that winter [of 1975-76]. I had gotten a heating bill for close to 100 dollars. They billed us after the fact in those days. They didn’t use a stick, they’d just come in and kind of look and estimate about how much oil you used out of your tank, and that’s how much you got the bill for. It was not very scientific. This bill was close to a 100 dollars and we had run the store for only three days. The rest of the time we used wood. I used it the first three days to get the cabin dried out; this was in one of the stone houses. So I called up the local furnace man and described the stove, which was one of those old little flame-type stoves. “How much heat would it use in three days?” And he said, “Probably ten dollars worth of oil, maybe less.” I wrote back to the park and I said this doesn’t work. I don’t see how it could be close to 100 dollars. There has got to be a mistake. They wrote back and said they’ve checked their records. You know how people are, they checked their records, sure. The have no records to check. “We have examined this thoroughly and you do owe this amount of money.” So I wrote back saying “I don’t feel I should be made to pay something that I don’t feel I should pay.” A fiery letter came back saying you will pay or else. So I said okay, wrote out the check and left the letter on the table and my wife [Linda] took it down and mailed it to the park. She goes around to our box there was a letter from Bett’s nephew, who had lived right across the road from us. Well, he lived in Hank’s house (26). We were living in 24. And he also had a high bill. This is the superintendent’s nephew. So he’d written the park and had gotten it reduced. So my wife reads the letter with this good news that the park reduced the bill. She went around to the window and asked for the letter back that’s going up to Crater Lake? So they found it in the mail and gave it back to Linda. Again, this is how little can changes the direction of your life. I got home that night and Linda says “The Nelson kid got his changed.” He was just married and had a little baby, same size house and everything. So I said, “I don’t think we should pay this thing. I think they still make mistakes.” So I wrote the fourth letter. And that’s when I found out about Mr. Betts. I got a letter about two or three days later. I opened it up and I was fired. He had gone to the files and changed my evaluation, which I found out later was illegal. But he changed it to no rehire after I had gotten high marks. He changed it and put me on the non-rehire list because this letter, which just smoked when you picked it up. This man was wonderful, but boy, this whole story is to show what kind of man Bettts was- very professional, but don’t ever get a letter from him. I cried when I got done reading that letter. Here I’d worked for the park for about 17 years and I suddenly was without a job for the summer. I was being disgraced. I was being thrown out for something where I was right and the park was wrong. I was absolutely devastated. I went over and looked up my brother first thing and I balled. I was 35 years old and I thought I’d lost my career with the Park Service. Lloyd still had his job, and we agreed we’d go up and try to talk Frank out of this thing. We went up and met Sholly for the first time. Sholly says let’s go see Frank. See what he can do about it. So we went into Frank’s office and talked. It was real stiff. He still hadn’t figured it out and he wouldn’t back down. So he got up, shook hands with Lloyd and said, “I’m sorry you’re not going to be here next summer.” Lloyd says, “No, it’s him.” So Lloyd almost got fired instead of me. I left absolutely crushed because I’d had a career jerked away from me for no fault of my own. We’d been talking about traveling back east, so that was the summer of ’76, and it was the Bicentennial. It was a good year to be on the road. So we took off. We spent the summer traveling.

He [Betts] was wrong in doing what he did, and I could have done all kinds of things. But I decided why make him angry. I needed the summer off, anyway. I started writing him cards from different parks. We went to about 30 different parks. Frank would see Lloyd walking in the parking lot and say “Hey, got a card from your brother today.” And Sholly would say “Got a card from your brother.” Well, by the end of the summer, they were calling him Larry. So then we never really discussed this afterwards, but I think Sholly knew I’d been done wrong. And I didn’t deserve it. By the way, they did cancel the bill totally. That was little consolation for losing my job, but I did win. Then Sholly called me one day and he said, “We need a dispatcher up here.” It was October, and they needed somebody to run the dispatch for hunting season. “Would you be interested?” He got me on in an emergency hire, where they don’t have to go through all the procedures. Here I am sitting there dispatching and Frank walks y, doesn’t say a word to me. I worked, I think, only two weekends and then Sholly kept me on as am employee. When it came May, he just converted me over. I didn’t have to fill out any applications or anything. I just went to work for him and I was back on with the Park Service. Frank and I never said another word to each other about it. But he accepted it. He didn’t try to get me, and say that guy’s not coming back. I think I proved myself by not making somebody angry. I have been trying to teach my son this, that there’s always a way of doing things if you know the man well enough and you work with him. I never got down on my hands and knees and begged. I never had to. That as just the way things worked out. He was very well liked, and if I remember it right, he was there about five years, well, no three. I was thinking he was there longer than that.

Then came James Rouse. His initials were JR. Because he was so short, they called him JR for junior behind his back. Very kind, had trouble making decisions, but his problem was he wanted always to listen to both sides, almost to a fault, before he’d make a decision. His policy was that he never wanted to make anybody mad. By using that policy, you usually make a lot of people mad. The thing that I really appreciated about Mr. Rouse was that he had great respect for the seasonal. He treated the seasonal as equals with permanents, especially the long-term seasonal. I’d be walking through the parking lot on Rim Rove. He’d be driving up, and he’d say “Larry get in the car. I need to talk to you about something.” And he’d bounce some things off of me. He’d just drive around the lodge, back again, and then he’d dump me out there by the visitor center. “Thanks” and be on his way. Or he’d call me in his office when I was down at the Administration Building. “Larry, I need to talk to you.” He’d come in and he’d take council from people or he’d have a question. What was really the neat thing about that man was he’d come to the evening programs. He just set a tone for the park that people seemed to really enjoy, at least the visitors. He was a very quiet man.

No.

Everybody just kept coming back?

During that time, I think I even make a comment, yeah, there’s a comment in the chronological history. Anyway, there was one season that every interpreter, I’d switched to interpretation by then, had come back that year. Among the patrol rangers there was no turnover at all for several years. Down at the entrance station, it was a bit more turnover and some turnover in maintenance. But, overall, it was a very stable time for the park. People loved their jobs and there was a lot of enthusiasm. Mr. Rouse had a lot of respect. I’d show a slide program and he’d say “Larry, I got some pictures you need. Come on over after work. I need to talk to you.” So I’d go over to his house and he’d have the slide projector all set up. He says “Are there any slides in here you can use?” He’d flip through them because he was at Teddy Roosevelt and some of the other parks. I needed some prairie pictures for Steel’s reading that article on the plains. That was one particular thing that I didn’t have any good prairie photos. I had taken a meadow picture and he said “That’s not good enough. You need a prairie picture.” So the one I have in my program is from Jim Rouse. I needed some elk pictures and he had all that stuff. He saw the need for that. He did it all on his own, a very kind individual.

I guess he’s going to retire this July.

Is he still at North Cascades?

Yes.

Last summer we planned to go and see him, but the summer shortened before we got up there. He was real proud of his buffalo chip. He had a varnished buffalo chip on a plaque in his office. That was his going away gift from Teddy Roosevelt. He prized it highly. He took our kids in there to show it to them and everything.

With Bob Benton, his ability to get things done, is real remarkable. I remember he made that statement “Crater Lake’s time has come.” And it had. He got through those historic preservation projects and I think you’re probably an outgrowth of his interest in history and so on. I’m so glad this position is even there (27).

Well, it isn’t at very many parks, western parks, that is.

Yeah.

There is still a lot of resistance to cultural resources in natural areas.

Well, back to your question about how I got interested in history. Well, part of it was I got good grades. I always got straight A’s in history, so that kept me going. Wanting to know what happened. The first thing in the park that I can remember was in ’64. The interpreters were upstairs, so I had a lot of interaction with them and so on. That was a real nerve center of the park. It was really nice having everybody in the same building. You weren’t in three or four different buildings, so you saw everybody everyday. The superintendent was always wandering through. The coffee room was upstairs. People were always together. The staff was relatively small, because everything was either at park headquarters or down at Medford. I was just flipping through some old things, and I saw an entry for the naming of Goodbye Creek. That’s what got me going on this chronological history. That is fascinating. It was goodbye to Mr. Arant (28). It was so exciting. I got a 3 x 5 card out and I typed up the thing and took it upstairs to the naturalist bulletin board and I put it up there. And I saw people gathered around it. Boy, wasn’t that interesting. So every time I’d find little things, tidbits, I’d type ‘em up and stick them up on the bulletin board. And that got me going on finding out why things were named. Then Larry Hakel decided one day that there should be a log kept of the park. I walked into his office and it was rolled up in his typewriter. He just started writing down things that were happening daily. That looked really interesting. I said, well, how about some of the things that happened this summer? So we added a few things there. And I thought, well, in 1916 this happened and in 1918 this thing happened. So I started scratching those things out and I said, why don’t we just make a log of a few things that people could reference.

The superintendent’s monthly reports must have been a good source.

My brother was keeping a file on the most asked questions at Crater Lake. He worked entrance station out north one year and I worked it south. People’d say “You know, rangers all look alike?” We had a lot of fun with things like that. I remember one day Lloyd and I were both standing on the rim, I was interpretation then and Lloyd was a patrol ranger. He got out of the patrol car and came over. We always tried to find each other and share a few tidbits. When I got off duty, I’d keep track of where he was in the park and I’d usually find myself there. I’d fill out the rest the afternoon and evening riding around with him. We spent a lot of time together. We’d have patrol schedules set up. I’d say, “Lloyd, I get off boats at so-and-so.” He’d say, “I’ll be going around the rim at that time.” So he’d pick me up and away we’d go. I’d be off duty, but it was great. I was on patrol for three years, off and on. It was a nice experience. But I remember this lady came up and she asked me a question and Lloyd answered. She did this little thing and she said “Did anybody tell you guys that you guys look alike?” And I said, “Ma’am, it’s the hat. If I put this hat on you, you’d look like us.” She never noticed our nametags. She just wandered off.

I was talking about going back, ,it’s going back to your childhood. It’s basically that Lloyd, my twin brother, and I were almost inseparable. I think our wives sometimes get a little jealous at our relationship because Helen comes from a large family and Linda has three brothers and they don’t have anywhere near the relationships with their family because one lives in Texas and one lives in Anchorage, Alaska. Another one lives in the Philippines and that type of thing. My brother and I have to talk to each other a couple of times a week. Even at our age we still write letters and notes back and forth to each other constantly. We have courier service between the schools and the counties. With one day service, if we need to send anything over we can just drop it in interoffice mail and it gets over there. So we’re always sending things back and forth.

So Lloyd teaches as well?

Yeah, he teaches at South Middle School in Grants Pass. So the park held a real special ness when we were living next door to each other. I have two kids and he has two kids. The cousins genetically are half brother and sister. So it’s strange, all four of them, none of them even come close to looking alike. They’re either tall, short, skinny, stocky-built, even the hair color doesn’t match. All four of the cousins, their personalities don’t come anywhere close to each other. So my son hated school, his cousin graduated valedictorian from Grants Pass High School. The cousins are very close, growing up together was an opportunity that most cousins don’t get. Our house were next door to each other for about eight years. For three or four years, Lloyd was on the first level of the Stone Houses and I was up in 24, so the kids had a trail that they ran back and forth on. So that’s another thing—Crater Lake was a family affair. On the fourth of July, my parents always came to Crater Lake. They brought their little motor home, parked it, and spent a week with us, every fourth of July because our birthdays were on the third. I was working one weekend up there on Valentine’s Day and it was Amber’s fifth birthday and so the whole family came up and spent the night with us. They brought their kids up and my parents came up and spent the night. We asked if we could use the school house, what do they call it now?

Community Center.

Community Center. I grew up knowing it as the school house (29). We asked if we could use it for dinner, oh sure, no problem. They gave us the key. We went over and cooked dinner there, the wives did. We had a big birthday party with the snow piled up ten feet high and the family all there.

It was only used as a school for a few years right?

It was used up through ’75, about ten years, I guess. That’s why Crater lake always holds so many memories because of our family connection with it. It just has a real special place in our heart. Those evenings when I would be on dispatch and Lloyd would be the only one on patrol, the Smith brothers had the whole park to themselves. Everything would work out. I remember how things work in threes. You’re heard this thing working in threes, well, working dispatch it always worked in threes. Airplane crashes tend to work in threes. One Sunday, we had a car accident. It was about three o’clock in the afternoon. I was on dispatch and Lloyd was on patrol. I called him out on it. The following Sunday, another car accident at three o’clock in the afternoon. Called Lloyd out on it. The third Sunday Lloyd had somebody riding with him and Lloyd looked at his watch real funny and he said “Well, it’s about three o’clock. It’s about time for an accident.” No sooner had he said that, then over the radio came” 323, there’s been a motorcycle accident just below the rim. Would you please respond to it.” The guy sitting there was flabbergasted. Here was the twin brother calling out the other brother right when he said it.

Some of the other changes you have on [question] number five about the concession I made a few notes on. The towns around the park haven’t changed. Fort Klamath’s about the same, Union Creek is the same, Chemult is as ugly as ever. Chiloquin is just as rowdy as ever. Those areas really haven’t changed. The real changes are in Klamath Falls and Medford. They no longer vie for the gateway to Crater Lake. Crater Lake is just one of many things. When I was growing up, Crater Lake was THE spot. There wasn’t a more important thing to have in this region. But now it’s interesting to see the newspapers don’t even carry very many articles about Crater Lake anymore.

It’s not a constant interest in the news media. It’s always the Tribune or Herald and News.

If it wasn’t for Lee Juillerat….

There wouldn’t be anybody steady doing it.

Right, and he works more toward the atmosphere and stuff like that (30).

We’ve been discussing some of the various seasons at Crater Lake.

I was talking about Hufnagel and some of the fun he was poking at the park. We were also talking about losing the badges. It was also when they decided to do away with the arrowhead. I remember when Hazrtzog tried to institute what we called the triangles with the mouse droppings (31). The tents and the mountains interlocking with the cannoballs to show history, which was a cheap imitation of what they already had.

So that’s what it was.

It was tents and interlocking of mountains and then the cannonballs to show history.

It’s not as successful a graphic as that environment (32).

Well, then, who had the dog? Johnny, the cleanup man?

Oh, Johnny Horizon? (33)

Johnny Horizon, is he still around?

No, they retired him.

We got a lot of Johnny Horizon stuff—comic books and posters that came into the park during that period. Boy, he was a real Mark Trail person (34). But I remember when that first started showing up on a few things, it was designed for Parkscape USA. It was the after-runner of Mission 66. So they came up with Parkscape. And that was the symbol.

They could get more funding for the expansion of the system?

Mission 66 ran out and so Hartzog’s idea with Parkscape was to have a program that was kind of non-ending. They weren’t going to put a date on the end of it. He went to a good buddy of his on Madison Avenue to come up with a symbol. So he came up with interlocking triangles. I remember the memo when it came out. It said “At no time ever, will this replace the arrowhead as the official Park Service emblem.” And within three or four years, it started showing up. That’s when they had those clubbed hands, you get the same thing, it looks like an Allstate ad (36). It was horrible for the Interior Department, the interlocking triangles. They dumped all the arrowhead stationary with the buffalo and the arrowhead on it. Then the brochure started coming out with inter-locking triangles on it. Slowly, it started moving. Then they decided they were going to go to the patch and do away with the arrowhead completely. That year, if you bought any uniform, you got it without anything on it. There was no patch.

Because they weren’t sure?

Right, the uniform makers wouldn’t take a chance on it so they just sent them blank. You’d sometimes get the patch, but usually the park had its own supply of patches. They went a whole year or two there with shirts with no patch on it. You didn’t have to take yours off, but they weren’t selling any with any on them. That whole period in the middle ‘seventies there was a lot of this back and forth, where people didn’t really know what they wanted for a park. Everything was being stylized, giving up the old values, painting over woodwork, whatever. The field just starting screaming about this arrowhead business, because the arrowhead had been designed from the field in about ’52 or ’53. Prior to that, all they had was the round circle with the Sequoia tree on it.

You can see the old boundary signs with the Sequoia on them.

If you watch Yogi Bear, Ranger Smith in Jellystone still wears the old symbol on his shoulder. He has the Sequoia tree symbol. The guy somehow has never updated that.

Back to a few of the changes of that [1960 to 1970] period. We were seeing the old guard changing and the new guard of bureaucrats that came in. Service is our middle name. Rangeroons, that’s it. Hufnagel had the little smoos. Are you acquainted with the smoos out of Al Capp? Little Abner’s smoos. But these are the little potbellied things and all they wore was a Ranger hat that went down below their eyes. They were the kind that stood offstage getting off the comments about what was going on in the cartoon. Hufnagel talked about service being our middle name, and it was. When I was running entrance station, our policy was that no matter who came in, at what time, and no matter how campers we had, we always found a spot for them.

So people weren’t turned away?

NEVER! It would be unheard of to turn anybody away. It was all free camping. Mazama was being extended at that time. So the Annie Creek campground was there at the curve, where the old headquarters was (37).

You can still walk on it. You can drive there today.

It’s still sitting there, a few rocks have fallen down. We could put about 25 there. Right where the entrance station is sitting now, where the road goes out, that was called the boondocks. It was a dusty area up through the trees that we’d just start shoving people up in there (38). We’d be so happy when we’d hit the campground count and we’d break a record over the previous night. It was exciting to be able to use Cold Springs, which was down by Polebridge (39). We’d put people in there. We’d put them in the picnic areas and when all that got full, we’d use the whole rim area. They weren’t encouraged to go around the rim and camp except in the rim parking lot. It was great. I remember one night we had seventy units sitting in the rim parking lot overnight and we were proud of the fact that we were able to find a home for those people. When the fee came in, oh, that was devastating. We had to start charging for something. It was horrible. The entrance station fee took care of that, supposedly, and then they started charging. We’re no longer the free Park Service like we used to be. Then, of course, it went up. It started at a dollar, two, then it went up. What is it, I think, about seven or eight dollars now? You’re not allowed to compete with private and so it’s based on a private fee with similar services. That’s what they are using.

Even though it’s higher than the other government campground in the surrounding areas.

Yeah, because Park Service campgrounds are not based on Forest Service rates. It’s based on what Crater Lake Lodge Company can get for equal service. In fact, I think they upped it to eight and backed it down to seven after a lot of complaints a year or two ago. We had a crew, I was on it for awhile, of three people and all we did was provide firewood for the campgrounds. You were expected to make firewood available when a camper came in and camped free. Those big bins that you see, down at Annie Springs, I mean at Mazama, were built and we kept them full to the top with firewood. You could just back up there and haul that stuff off like butter. One day they started looking at the cost of that. It was a pretty expensive thing to do and it wasn’t really in keeping with the Park Service because they were cutting up every dead tree that they could get their hands on. We weren’t falling anything, but all the winter stuff that went down was all cut up.

This isn’t really related, but how did the idea of the Corrals come about? I found the design sheet for this bizarre idea for an overlook (40). How did that come about?

Well, I was told it was to save the white bark pine out there. The idea was to build it sturdy enough so that the people wouldn’t walk through it and it wouldn’t collapse in the wintertime. Those are just peeler logs that they were using basically. So it was fairly cheap. But the oldest white bark there is drying because of the damage that had been done to it already. All it would take is somebody to run out there with a dump truck of pumice and fill that void up. But if you’ve noticed, it’s dropped two feet around there. The wind is just slowly scouring because it was part of a road cut. I was noticing last summer the top part of that old white bark is almost dead. That thing is 300 or 400 years old. If somebody just dumped some dirt on it. Why can they be so blind to that solution, especially when it was designed to save that tree? Have you noticed there are some young ones coming up along there, which is kind of encouraging. But basically it’s just become a wind trap for the paper and it swirls around in there and you always have a mess from all the litter that lands in there.

I noticed in having done hikes to the top of Watchman, it’s very difficult to recruit, to get away from the Corrals.

Yeah, because they’re the rim drivers. I counted one time about 150 cigarette butts out there one day. I had a few minutes before I had to go around the rim, so I just got down on my hands and knees and started picking up trash and all the cigarette butts. So ever since then, every time I see anybody throwing a cigarette butt down, I say, “You know, somebody’s going to have to pick that up.”