United States Geological Service, Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center

U.S. Department of the Interior

Research Brief for Resource Managers

|

Release: |

Contact: | Phone: | Email: |

| March 2003 | Gary Larson1 | 541-750-1032 | gary_l._larson@usgs.gov |

| Robert Collier2 | 541-737-4367 | rcollier@coas.oregonstate.edu | |

| Mark Buktenica3 | 541-594-3077 | mark_buktenica@nps.gov | |

|

1 Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center, 777 NW 9th St., Suite 400, Corvallis, OR 2 Oregon State Univ., Dept. of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences, 354 Burt Hall, Corvallis, OR 3 National Park Service, Crater Lake National Park, P.O. Box 7, Crater Lake, OR 97604 |

|||

|

| WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT IT? |

Crater Lake covers the floor of a steep-sided caldera formed 7,700 years ago during the violent volcanic eruption of Mount Mazama followed by collapse of the mountaintop. The average lake level is 1,883 meters above sea level, but for periods of 5 to 10 years lake elevation can vary as much as 5 meters. The lake has a surface area of 54 square kilometers and a maximum depth of 594 meters, making it the seventh deepest lake in the world. The scalloped edge of the caldera is about 8 kilometers in diameter, varying in elevation from 159 to 586 meters above the lake surface. Essentially, the lake rests in a “leaky pot,” losing water only through seepage and evaporation. The lake’s surface elevation rises and drops relative to the amount of snow and rain that falls on its surface.

|

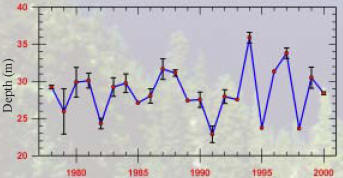

| FIGURE 1. Mean Secchi disk depths in August. |

The lake is among the clearest in the world and its waters appear deep blue in color. When sunlight penetrates into the lake, the red and green portions of the light are preferentially absorbed by water and suspended particles. The blue light, which penetrates more deeply, is eventually scattered by water molecules and returns to the lake surface and our eyes. The blueness of the water is greatest when the sun is bright and the particle density is very low. A 20 centimeter black and white disk, known as a Secchi disk, is used to measure the water clarity. In summer, the disk can be seen to a depth of about 30.5 meters, but clarity readings range from under 20 meters to over 40 meters. Changes in water clarity are related to the amount of algae (or phytoplankton) suspended in the lake, as well as particles eroded from the lake shoreline and carried by runoff from numerous small streamlets that enter the lake. Changes in lake water clarity are a natural part of the lake system (Figure 1).

The maximum surface temperatures in August are generally near 18°C. The bottom of the lake has a year-round temperature of about 3.6°C, which is warmed very slightly by the input of geothermal fluids. These fluids also contribute dissolved salts to the lake, creating a much higher salt content than would be expected if direct precipitation were the only source of input.Crater Lake seldom freezes in winter because the great mass of water, although very cold, retains enough heat to keep the surface free of ice. Only during exceptionally cold, windless periods does a thin layer of clear ice cover the lake. This has only happened three times in the last 100 years. During winter, strong winds mix the upper lake waters down to a depth of over 200 meters; however, the deep parts of the lake exchange with the surface only periodically when cold, dense water sinks to the bottom. This process, which appears to be focused along the edges of the lake, forces deep water to “upwell” into the wind-mixed portion of the lake. This physical process occurs annually, but its magnitude varies from year to year due to different weather patterns. Upwelling water is important to the ecology of the lake because it contains nutrients that are important for photosynthesis by algae. The nutrients build up in the deep lake from the decomposition of organic particles sinking to the lake floor; however, the overall concentrations of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus are very low in the lake which is why algal growth is low in the first place. In summer, thermal stratification of the lake results in a warm, less dense surface layer called the epilimnion that floats on top of the deep, cool, dense layer called the hypolimnion (Figure 2). The transitional zone is called the metalimnion.

The maximum surface temperatures in August are generally near 18°C. The bottom of the lake has a year-round temperature of about 3.6°C, which is warmed very slightly by the input of geothermal fluids. These fluids also contribute dissolved salts to the lake, creating a much higher salt content than would be expected if direct precipitation were the only source of input.Crater Lake seldom freezes in winter because the great mass of water, although very cold, retains enough heat to keep the surface free of ice. Only during exceptionally cold, windless periods does a thin layer of clear ice cover the lake. This has only happened three times in the last 100 years. During winter, strong winds mix the upper lake waters down to a depth of over 200 meters; however, the deep parts of the lake exchange with the surface only periodically when cold, dense water sinks to the bottom. This process, which appears to be focused along the edges of the lake, forces deep water to “upwell” into the wind-mixed portion of the lake. This physical process occurs annually, but its magnitude varies from year to year due to different weather patterns. Upwelling water is important to the ecology of the lake because it contains nutrients that are important for photosynthesis by algae. The nutrients build up in the deep lake from the decomposition of organic particles sinking to the lake floor; however, the overall concentrations of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus are very low in the lake which is why algal growth is low in the first place. In summer, thermal stratification of the lake results in a warm, less dense surface layer called the epilimnion that floats on top of the deep, cool, dense layer called the hypolimnion (Figure 2). The transitional zone is called the metalimnion.

The algae in the lake are diverse in species but sparse in abundance. Over 150 species have been detected and algal abundance has varied considerably through the years (Figure 3). In summer, when the lake is thermally stratified, different algae species live in different layers of the water column down to a depth of about 200 meters (Figure 4). Because of the extreme clarity of the lake, the maximum amount of photosynthesis is able to occur at 40-80 meters. Phytoplankton that are adapted to very low light levels can produce a chlorophyll maximum at 120-140 meters (Figure 5).

The algae in the lake are diverse in species but sparse in abundance. Over 150 species have been detected and algal abundance has varied considerably through the years (Figure 3). In summer, when the lake is thermally stratified, different algae species live in different layers of the water column down to a depth of about 200 meters (Figure 4). Because of the extreme clarity of the lake, the maximum amount of photosynthesis is able to occur at 40-80 meters. Phytoplankton that are adapted to very low light levels can produce a chlorophyll maximum at 120-140 meters (Figure 5).

Two species of fish inhabit Crater Lake. Both were stocked into this naturally-fishless lake. These include kokanee salmon (landlocked sockeye salmon) and rainbow trout. The latter inhabit the nearshore area of the lake and feed on large-bodied terrestrial insects that fall onto the lake surface, aquatic invertebrates living on the bottom of the lake, and kokanee salmon. Kokanee feed on small-bodied terrestrial insects and bottom fauna, and crustacean zooplankton. Kokanee live in the open waters of the lake to a depth of about 150 meters and, to a lesser extent, along the shoreline of the lake. Fish may have altered the species composition of the lake and have assumed the role of top predator over zooplankton. This may have had cascading effects throughout the food web.The animal plankton (zooplankton) in Crater Lake include nine rotifer species (microscopic multicellular animals 0.20-1.52 millimeters in length) and two crustacean species (0.45-3.12 millimeters in length). The abundance of zooplankton varies greatly through time (Figure 6). Some species are present every year, whereas others occur infrequently. During summer when the lake is thermally stratified, different species live in different portions of the water column down to a depth of about 200 meters.

WHY CONTINUE TO STUDY CRATER LAKE?

Crater lake is a world-class laboratory for studying lakes because of its pristine condition. Because it is preserved in a national park it is expected that there will be minimal future onsite impacts from human activities. The lake provides scientists and park managers with a gauge for assessing changing environmental conditions external to the Park. Long-term monitoring of Crater Lake has been used to develop a baseline of information about the natural dynamics and complexity of the lake. This baseline will serve as a reference when studying the impacts of global climate change and human activities, such as agriculture and urban growth, on other lakes. Scientists working with the U.S. Geological Survey, the National Park Service, and Oregon State University have systematically studied Crater Lake for the last two decades. Long-term monitoring of this lake is a priority of Crater Lake National Park and will continue far into the future.

The long-term lake program involves studying many components of Crater Lake. Currently, the relationships between many of these model components are being investigated using mathematical models. Based on this research, new studies will be undertaken to refine our understanding of how these components interact. Once the models are completed, researchers will have a better understanding of how the lake “works” and how the lake may respond to future environmental changes.

THIS DOCUMENT WAS CREATED IN COLLABORATION WITH OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY AND CRATER LAKE NATIONAL PARK.

THIS DOCUMENT WAS CREATED IN COLLABORATION WITH OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY AND CRATER LAKE NATIONAL PARK.