The Geology of Crater Lake National Park, Oregon With a reconnaissance of the Cascade Range southward to Mount Shasta by Howell Williams

The Main Andesite Cone of Mount Mazama

Building of the Main Andesite Cone

As far as can be determined, Mount Mazama rose to its greatest height almost solely by eruption of hypersthene andesite. Not until it had practically gained full stature did the feeding magma begin to differentiate toward basalt and dacite.

Of the early history of the volcano there is now no visible record. Presumably, activity began from a single, central vent, though it is clear from the attitudes of the lavas on the caldera walls that early in its growth the volcano was supplied with additional vents, or that the principal vent shifted from time to time.

The oldest of the visible lavas seem to have issued from a vent close to the Phantom Ship, on the south wall of the caldera. We may speak of this as the Phantom vent, and call its products the Phantom cone. The filling of the vent forms a bold triangular face about a third of the way up the caldera wall (plate 6), and is composed of massive, brown-crusted, pale-green vesicular andesite heavily charged with lamprophyric inclusions and cut by darker-green andesite similar to that forming the dikes on Phantom Ship. All but the northern edge of the vent is concealed by talus, but on that side the margin cuts vertically across the enclosing lavas and breccias. In plan, the vent is approximately circular and measures between 200 and 250 yards in diameter.

|

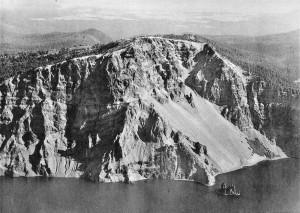

Plate 6. Dutton Cliff and Phantom Ship. The triangular cliff in the center of the picture is the filling of a vent, possibly the oldest on Mount Mazama. From this, the Phantom Cone was built, of which Phantom Ship is part. The lakeward dips of the lavas and breccias of this cone are clearly shown. After extinction, the Phantom Cone was eroded and then buried by flows from the main vents of Mount Mazama. Note unconformity on the east (left) side between the Phantom and Mazama lavas. A second unconformity, among the Mazama flows, appears higher up the cliff. Thin glacial deposits occur at this horizon, and water seeps issue from them. (Photograph by U. S. Army Air Corps.) |

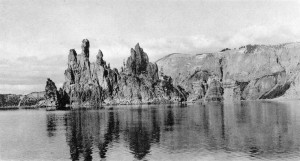

That we are really dealing here with the filling of an old volcanic conduit is indicated also by the arrangement of the surrounding rocks. Close to the vent lie inward-dipping, red tuff breccias containing blocks of andesite up to 8 feet across. Farther from the vent, toward the lake, the breccias and interbedded lavas dip outward at angles up to 40°. At the base of the spur that projects toward the Phantom Ship, pale-green lapilli tuffs, similar to those on the Ship itself, dip lakeward at high angles. No doubt the Phantom Ship is a remnant of the Phantom cone and the dikes that make its mimic sails are radial offshoots from the central pipe (plate 7, figure I).

|

Plate 7, Figure 1. Phantom Ship, an islet in the lake, composed of tuff breccia cut by vertical, branching dikes, distinguishable by their dark color. Of the five “sails,” the ones at each end and the low one in the middle are parts of the dikes. So is the dark band at the base of the other two “sails.” (Photograph by H. B. Taylor.) |

How high the Phantom cone rose it is impossible to tell, for after activity ceased, the summit was eroded and buried by flows and other ejecta from the central vents of Mount Mazama. The unconformity separating the Phantom flows from those of Mazama proper is plainly visible in plate 6. Finally, after the Mazama lavas had entirely buried the Phantom cone, a long period of glacial erosion ensued in this vicinity and a layer of morainic detritus accumulated on the surface. When flows again poured in this direction from the central craters of Mazama, they continued to accumulate to a thickness of more than 1000 feet, and now form the unscalable upper half of Dutton Cliff. The level of this second unconformity is marked by water seeps from the interbedded moraine.

The Phantom cone was, of course, trivial in size as compared with the main cone of Mount Mazama. From the dips of the lavas on the caldera walls, it may be estimated that the principal vents of the major cone lay, not directly above the center of Crater Lake, but between half a mile and a mile to the south, or a little east of south. In other words, Crater Lake is eccentric with respect to the former cone of Mazama. This is suggested at once by the fact that on the south side of the lake the caldera walls are much higher than on the north. The reasons for this eccentricity of the caldera with respect to the cone are discussed later.

***previous*** — ***next***