Crater Lake National Park: Administrative History by Harlan D. Unrau and Stephen Mark, 1987

***previous*** — ***next***

CHAPTER NINE: Legislation Relating to Crater Lake National Park: 1916-Present

D. UNSUCCESSFUL EFFORTS TO EXPAND PARK BOUNDARIES

From the 1910s to the 1940s the National Park Service initiated a series of efforts to expand the boundaries of Crater Lake National Park. The primary purpose of these efforts was to enlarge the park to provide recreational opportunities and park facilities for visitors away from Crater Lake itself, and thus curtail or eliminate development that would mar the scenic and scientific qualities of the lake. A secondary purpose of the proposed expansion was to create an enlarged game preserve to protect the wildlife of the region. The focus of the expansion efforts was the Diamond Lake-Mount Thielson-Mount Bailey region to the north of the park and the Union Creek-Upper Rogue River Valley to the west.

In his first annual report NPS Director Mather recommended that the Crater Lake park boundaries should be extended northward to include the Diamond Lake region. This addition, according to Mather, would offer the tourist a variety of scenic features that “would compare favorably with the diversity of scenery in most of the very large mountain parks.” Other advantages of the Diamond Lake extension were:

Diamond Lake lies a few miles north of the park in a region that is valuable for none other than recreational purposes. Fishing in the lake could be improved and the region around about it made attractive for camping. A chalet or hotel, operated in connection with the hotel on the rim of Crater Lake, could be constructed near Diamond Lake when travel to the park warranted these additional accommodations. It would be reasonable to expect that the majority of visitors to Crater Lake would not overlook an opportunity to see the wonderful scenic region to the northward. Besides Diamond Lake the proposed addition to the park would include Mount Thielson, a peak considerably over 9,000 feet in altitude and known as the “lightning rod of the Cascades,” because during electric storms brilliant and fantastic flashes of lightning play about its needlelike summit.

Mather stressed that the addition of the Diamond Lake and Mount Thielson areas could “not be too strongly urged.” A branch road from the main highway from Medford already made the Diamond Lake country accessible, and at some future time “a circle trip might be provided by the construction of a road from the north rim of Crater Lake to Diamond Lake.”

A second park extension recommended by Mather was the Lake of the Woods region just south of the park. While the area had not been investigated by representatives of the National Park Service, it was “known to be an exceptionally beautiful region and valuable for scarcely anything besides park purposes.” [71]

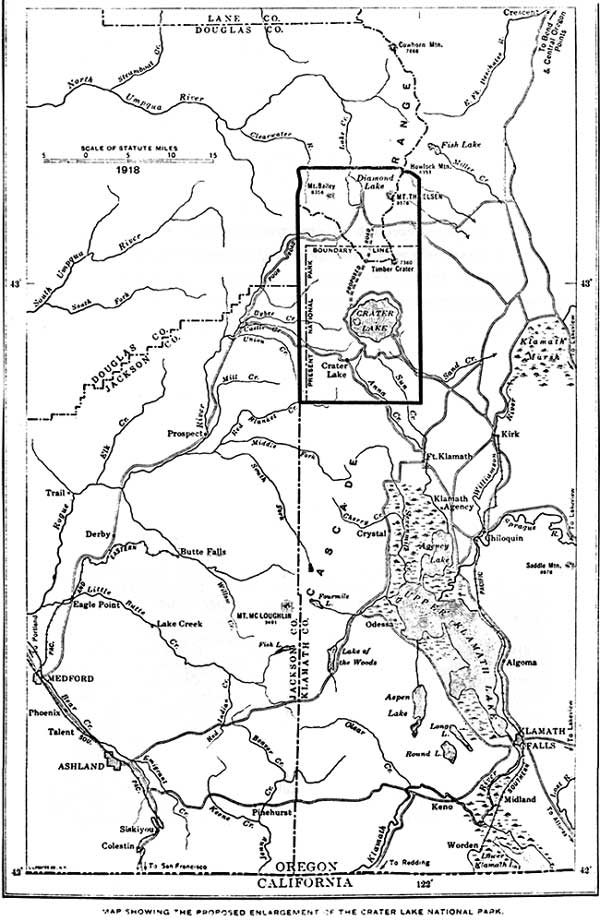

As a result of Mather’s continuing lobbying efforts Senator McNary introduced legislation (S. 4283) on April 6, 1918, to provide for the transfer of some 92,800 acres of national forest land to the control of the National Park Service for addition to Crater Lake National Park. The proposed extension included a 3/4-mile strip of land on the western boundary as well as the principal nine-mile northward enlargement to include the Diamond Lake region (see map below). In support of this bill Mather noted:

When the park has been enlarged as proposed by this measure an opportunity will be afforded for developing to a very much greater extent the camping facilities of this region. Diamond Lake will lend itself to development as a fishing resort of great importance and other recreational features will be added that will, in a few years, make this park as great a resort as most of the very big national parks. This is its manifest destiny. Furthermore, the enlargement of the park will make conditions more satisfactory from the point of view of the development of first-class transportation, hotel, and camp accommodations, because the traveling public can be induced to spend more time in the park than ordinarily is the case at the present time. More roads will be built, opening up unusually interesting territory, and providing circle trips that will delight the traveler. A road connecting Crater and Diamond Lakes would be a natural development. The addition will also afford better opportunities to protect the wild life of the park.

Like the proposed extension of the Yellowstone National Park, the addition of the Diamond Lake region to Crater Lake would give to the national park system something that was intended by nature always to be the property of the Nation and to be developed as a recreational area for all the people. . . .[72]

Map showing the proposed enlargement of the Crater Lake National Park.

Diamond Lake is 5,200 feet above sea level and is almost rectangular, 2-1/2 by 5 miles, its south end being 5 miles north of the present park boundary. It is beautifully located and furnishes an ideal camping ground. To the east and south the shore is grassy, with a gradual slope to a pebbly beach, making it possible to walk or ride into the water, which is shallow for some distance. By reason of its shallowness, the water becomes warm enough for comfortable bathing.

This lake offers a strong contrast to Crater Lake, in which bathing is out of the question and which is reached only by a trail built at considerable expense. . . .

Mount Thielson is directly east, and Mount Bailey west of Diamond Lake. The region comprising these three scenic attractions rightfully belongs to the park not only as a recreation ground but as a game preserve.

Crater Lake Park is too small for a game preserve. Many of the deer get quite tame and it seems like murder to kill them when they stray across the boundary. One case in point occurred recently during the hunting season. Voley Pearsons, of Klamath Falls, shot a doe on the road about 300 yards outside the southern entrance to the park. The doe had frequently visited the ranger’s cabin and was so tame that it would not run when an auto approached. As it is unlawful to kill a doe at any time, the man was arrested by the Park Service and turned over the local authorities at Fort Klamath, where he was fined $25 and costs. This case is cited only as evidence of the necessity of enlarging our game preserve. [73]

The legislative struggle to add the Diamond Lake extension to Crater Lake National Park continued for several years. The McNary bill died in the Senate Committee on Public Lands in 1918, but he reintroduced the legislation (S. 2797) on August 15, 1919, calling for an extension of some 94,880 acres. On April 5, 1920, the Senate passed the bill, but it encountered opposition in the House Committee on Public Lands. The opposition was based on Forest Service objections, claiming that the extension area was “more valuable for commercial use of one kind or another than for recreation uses of those who visit the park.” Among the commercial uses contemplated by the Forest Service were grazing and use of Diamond Lake as a source for power generation. Local citizens supported the Forest Service because of the good hunting prospects of the region and the agency’s willingness to lease Diamond Lake shore property for construction of summer cabins and recreational concessions.

The Senate bill failed to be reported by the House committee, and on July 18, 1921, McNary introduced a new bill (5. 2269) to provide for expansion of the park. As this third bill entered the legislative arena, Mather supported it in ever more strident terms. In his annual report for 1921 he stated:

Progress in the development of Crater Lake Park will shortly be retarded if Diamond Lake is not added. This remarkable lake, with its stately forests, its broad sandy beaches, its rugged mountains, and its unexcelled opportunities for bathing and fishing, naturally belongs to the park. Physically it is a part of the park, but legally it has no relation to it. In the extension of hotel and camp facilities and transportation lines this region is essential to the success of a comprehensive development. The utilities of the present park should have opportunities to encourage visitors to remain longer in the country. This can not be brought about unless more attractions are available. Diamond Lake has all that will ever be required to round out a park trip. It will diversify a tour almost as much as any national park in the system, and in so doing will add tremendously to the pleasure of a visit to southern Oregon.

It will be very easy to build a road from Crater Lake to Diamond Lake; in fact, several automobiles traversed the route of the road during September. The first automobile over the route carried Vice President E.O. McCormick, of the Southern Pacific Lines, and Superintendent Sparrow. The trip was made on September 1 . I have been advised by both of these gentlemen that the cost of building a road between the two lakes will be very small.

Opponents of the extension plans, which appear to be few in number, contend that Diamond Lake is required for power purposes, and that surrounding lands are needed for grazing. Upon careful inquiry I can not find that these objections are worthy of serious consideration; certainly the immediate recreational advantages of the region far outweigh the future possibility of utilizing the lake for power storage, and as for the grazing argument, there never has been much pasturage of live stock about the lake, and it is inconceivable that in order to meet the wishes of a very few owners of cattle and sheep a great project of this kind, national in character, should be condemned . . . . [74]

The third McNary bill failed to receive the favorable endorsement of the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys, and thus the Diamond Lake extension issue lay dormant for several years. The Park Service continued to make pleas for the preservation of the scenic values of the region, but little could be done with the growing opposition of the U.S. Forest Service, the Diamond Lake concessionaires operating under Forest Service lease, the owners of private cottages, the State Game Commission, and grazing and hunting interests. [75]

In 1926 the Park Service focused its efforts on Crater Lake National Park expansion by submitting proposals to the President’s Coordinating Committee on National Parks and Forests. The committee had been established to investigate and make recommendations regarding transfer of lands between the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service. In August the committee held hearings regarding Crater Lake expansion in Klamath Falls, Diamond Lake, and Medford. The Park Service recommended three extensions to the park boundaries- -areas that were of outstanding scenic and recreational value that would relieve the park of administrative burdens that were “fast becoming critical.” The three extensions were:

1. DIAMOND LAKE EXTENSION: The proposed extension is in general accord with the McNary Senate Bills, but reduces Senator McNary’s proposed extension by 36 square miles. This extension would bring the Park boundaries one mile north of Diamond Lake and would include Mounts Thielson and Bailey.

Area embraces approximately 83.5 square miles.

2. UNION CREEK EXTENSION: This is an extension westward that includes a portion of the headwaters of the Rogue River; to secure the immense recreational opportunities of the Union Creek area; to secure gravity water supply; and to provide an all-year Park headquarters of vital importance to administration .

Area embraces approximately 34 square miles.

3. KLAMATH EXTENSION: A small extension southward, worked out on the ground with the Forest Supervisor, to secure mutually advantageous positions.

Area embraces approximately 3.8 square miles.

The Park Service also proposed the elimination of three areas from the park. The three areas contained valuable timber, grazing tracts, and private inholdings that were a source of irritation to park administration. These areas were:

1. NORTHEAST AREA: Designed to eliminate 12 square miles from the northeast section of the present Park, an area containing a very valuable stand of mature yellow pines, very accessible, contiguous to timber now being marketed under Forest supervision. Immediately marketable yellow pine in this area is estimated by Forest Service officers at 100,000,000 board feet.

2. NORTHWEST AREA: To eliminate 18 square miles of timber and grazing desired by the Forest Service. Also desired by them to improve the administration of the Crater National Forest by giving access to sources of streams, and a better topographical boundary.

3. SOUTHEAST AREA: Eliminate approximately 13 square miles of valuable timber land contiguous to Forest timber now being marketed. It also eliminates private holdings that embarrass Park administration.

All told the proposals provided for a total extension of the park boundaries of some 118 square miles and eliminations totaling 43 square miles for a net enlargement of 75 square miles. As a result of continuing opposition by the Forest Service, however, none of the proposed park extensions or eliminations were approved. On August 6 the committee met in Medford and voted unanimously to disapprove all of the Park Service proposals. Later in 1932 a portion of the proposed Klamath extension would be added to the park, thus providing for a more attractive southern entrance amid a stand of yellow pine. [76]

It is interesting to note that Commissioner Steel, who had begun the campaign to add the Diamond Lake region to the park in 1914, opposed the extension in August 1926. Writing to the President’s Coordinating Committee on August 3 Steel provided the rationale for his change of mind:

About ten or twelve years ago, while 1 was superintendent of the Crater Lake National Park, I started a movement to extend the boundaries of the park, so as to take in Diamond lake, but since then my mind has changed, for I have come to realize it is not for the best interests of the park.

Diamond lake is a beautiful sheet of water, similar to hundreds of others throughout the country, with no national features, but very dear to local residents, who love to camp there during the Summer, together with their families and enjoy a relief from business cares, in the mountain wilds. It is exclusively local in character and should be left free of such restraints as go with a great national attraction, which it is not. It has no interests in common with Crater Lake and the two should not be combined.

In a spirit of local pride certain citizens of Southern Oregon have invested money in its development in good faith, under a concession of the Agricultural Department, trusting in the honesty of that branch of the government, and suspicious of the Park Service, because of the fact that the only man on earth who was willing to invest his own money at Crater Lake, was dispossessed of his concession, which was given to others, no better able to make good than he.

The inclusion of Diamond Lake in the Crater Lake National Park, means an immense increase of fire hazard, because of the vast area of dead and down timber, to which there is no offset in benefits. . . .

If an addition is desired to the park of real benefit, the Western line should be extended, so as to protect deer that move down in that direction, just in time to be slaughtered by hunters in the Fall. [77]

Park boundary extensions again became a political issue in April 1932 when Superintendent Solinsky recommended that approximately 400 square miles of Forest Service lands be added to Crater Lake. This extension included not only the Diamond Lake-Mount Thielson-Mount Bailey region but also the Upper Rogue River Valley and Union Creek area west of the park. Prior to this time nothing as large as Solinsky’s recommendation for the Union Creek extension had ever been contemplated. The opposition of the Forest Service, which viewed the proposed westward extension as a “land grab,” and the combined opposition of that agency and various private and commercial interests in the Diamond Lake area doomed the proposal to defeat. [78]

In March 1936 Acting NPS Director Arthur E. Demaray revealed several heretofore unspecified reasons for the continuing interest of Park Service officials in Diamond Lake. Among other things he observed:

Diamond Lake has always been considered essential to the Crater Lake unit. Its inclusion within the park was advocated and sponsored by organizations throughout Oregon as early as 1915, but the Forest Service defeated the project and the Lake was promptly developed as a summer home and recreational area. Since that time we have been forced to concentrate more developments at Crater Lake than we consider appropriate or desirable.

Because of the high altitude of Crater Lake it has been necessary to establish both a summer and a winter headquarters for the park. We did not advocate the inclusion of Diamond Lake as a competing and detracting exhibit; we advocated it for the protection of Crater Lake, so that Crater Lake would not be marred by overdevelopment. It might be said that Diamond Lake could perform that function in the national forest just as well as it could if it were in the park. Theoretically, that sounds fine, but the simple facts are that Diamond Lake has never been developed to take care of the Crater Lake visitors and it does not perform that function. It has been given over to a different type of land use.

Demaray concluded, however, that the question of the extension, while a worthy conservation cause, had become so misrepresented by various interest groups that it had “almost assumed the reputation of the Bad Man from Bodie.” [79]

Later that year the Diamond Lake extension issue surfaced again when Senator Robert F. Wagner of New York and NPS Director Arno B. Cammerer visited the Diamond Lake area. The purpose of the visit was to continue discussions of the possibility of adding approximately 55,000 acres to Crater Lake National Park, including the lake for “its recreational and fishing advantages.” When the Department of the Interior publicized its intentions, however, opposition by the local press and various citizens’ and government organizations in Southern Oregon mounted, thus forcing the department to drop its plans. [80]

The final thrust of the Park Service to gain the Diamond Lake and Union Creek extensions occurred during the summer of 1939. A “Preliminary Report on Extensions to Crater Lake National Park,” was prepared on September 2 to provide the background material for the proposals. The report analyzed the accessibility and the general characteristics of the areas, including scenic, scientific, historical, interpretive, and recreational values. In submitting the report to NPS Director Cammerer, Superintendent Leavitt concluded:

Recreational values are of the most importance in considering extensions to the park. The physical features of the park make possible limited recreational use. Extended development of recreational facilities in the park could seriously endanger unsurpassed scenic values. If the policy of the Service is to expand recreational activities under clearly defined land use standards, Diamond Lake particularly should be given consideration as an addition to the park. Both the Diamond Lake and Union Creek sections contain recreational opportunities lacking in the park. The Diamond Lake area could provide a greater variety of recreation involving much less timber value, and greater scientific and educational values in relation to Crater Lake than the Union Creek area. [81]

This last serious effort to acquire Diamond Lake and Union Creek foundered on public and Forest Service opposition This combined opposition, coupled with the coming of World War II, forced the issue into abeyance and was never considered seriously again.[82]

During 1945-47 efforts were made to enlarge the panhandle addition to the south boundary of the park. Discussions were held with U.S. Forest Service officials to enlarge the section by extending the east and west boundaries back to section lines. The Park Service desired the expansion for the following reasons:

The straightening out and enlarging of this tongue-like addition to the park along section lines would be very desirable. Fires that start adjacent to the park have to be handled by the staff of Crater Lake National Park, because they are able to reach the area more quickly than the Forest Service. This narrow, irregularly shaped addition to the park is not easily recognized by the fishermen, hunters or trappers, even though the boundaries are marked, and trespassing on or across this narrow neck often occurs through ignorance or carelessness.

The south entrance has now become the road entrance carrying the heaviest travel, and development has been started for a small utility area there right on the edge of the south and west boundaries. If at some future time Park Headquarters should be established at the south entrance, there would not be sufficient room for the development that would be required. It is therefore very important that this area be enlarged and straightened out while the opportunity presents itself, for administrative reasons and to provide an area sufficiently large to permit all the headquarters area and utility development that will be required in the future.

Despite some friendly overtures by local Forest Service officials, however, the effort was disapproved by regional and Washington office representatives of that agency. [83]

Appendix A9: Legislation, January 25, 1915

Appendix B9: Legislation, August 21, 1916

***previous*** — ***next***