Although Sparrow reported that the park’s trail system in 1918 as consisting of 22 miles, part of this total included rough one-lane service roads built in conjunction with a trail of varying standard.33 An example was the “trail” of four miles or so built in 1918 for light vehicles and horses toward the base of Union Peak. It started from a point about half a mile west of Annie Spring on the Medford Road (built by the Corps and following the same general alignment as Highway 62 later on) and ran in a southwesterly direction. Much of it consisted of a track cut about sixteen feet wide, in order to improve it for automobiles in the future. Reaching the top of Union Peak still required an almost cross country climb of some 700 feet over the last quarter mile, with a “safe and easy” ascent required to reach the summit from the end of this trail.34

Sparrow also described a point about one-eighth of a mile from the base of Union Peak, where a blazed track commenced toward Bald Top and Red Blanket Canyon, some two miles away. Described as rough and still poorly defined, but practical for pack animals, Sparrow saw it as primarily useful for future ranger patrols. As a way of preventing poaching and limiting the spread of wildfires, the route left the park near its southwest corner. It represented a link with trails built by the U.S. Forest Service on the adjacent Crater National Forest, but especially what Sparrow called an “outlet down Dry Creek toward the Wood River Valley,” he pledged that the rangers using the route would improve it.35

|

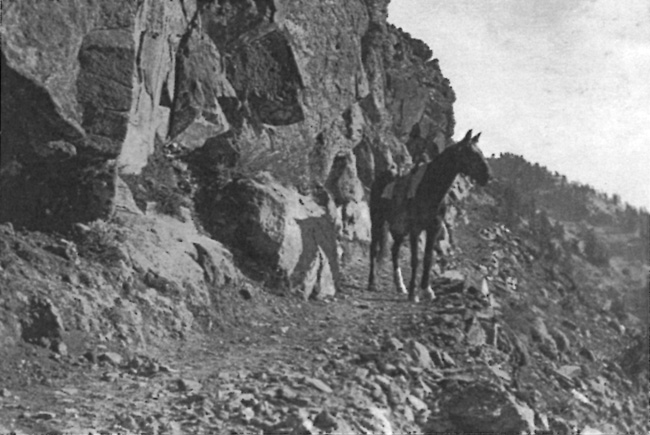

| “The Imp,” Superintendent Sparrow’s horse, on the trail from lodge to Garfield Peak, November 1917. Photo by Alex Sparrow, author’s files. |

Sparrow still counted the Bybee or Copeland route (which was likely a trace leading north from Dutton Creek and then west toward the park boundary) as part of the park’s trails, but he figured its length at only 2.2 miles. He also listed some former wagon routes as trails, such as the one running from Annie Spring over to Dutton Creek and then to the rim. It covered a distance of four miles, while another wagon road segment one mile in length built by Arant connected Munson Valley with Rim Village.36 Sparrow described a foot trail to the crater on Wizard Island (built when Steel served as superintendent) as good, but wanted it widened (to four feet) and extended for a distance of 5,000 feet. The route to the top of this cinder cone had not received specific mention in the annual reports written by park superintendents to this point, though some visitors climbed to the island’s summit by way of an informal track since 1896.37 The trail to Sentinel Point, built at Mather’s behest in 1915, had meanwhile become popular enough for the NPS to place signs as part of alerting visitors to the viewpoint.38