Finishing most of the construction on the Crater Wall Trail in 1928 came during the initial stages of redeveloping the sometimes bleak and dusty site of Rim Village, where visitor services with their associated impacts had long been concentrated. The trailhead was situated near a newly-built parking area, something largely intended for day use, as part of a larger plaza containing the concessionaire’s cafeteria. The plaza still needed to be connected with other key features in Rim Village, such as the Crater Lake Lodge and Rim Campground. This could be accomplished by means of a roadway, but also through a network of walkways. Plans for pedestrian circulation at Rim Village centered on building a promenade eight feet wide and running some 2500 feet long (or roughly the distance between the trailhead and lodge), to be located along the edge of the caldera. Work on the promenade thus began in 1928 and continued over the next four summers. The NPS intended to concentrate foot traffic on the promenade and associated walkways (both of which were to be paved) as a way to harden the site, yet this allowed the agency to also take steps toward restoring native vegetation through planting. Officials also planned to use the promenade as a means to unify Rim Village, especially once masonry walls could be erected as a safety barrier on the side facing Crater Lake.61

While both the Crater Wall Trail and a promenade in Rim Village represented improvements to pedestrian circulation in an area where more visitors congregated than anywhere else in the park, they were not the only construction projects undertaken by the NPS at Crater Lake during the summer of 1928. Federal funds aimed at new buildings and roadwork continued to far outstrip those for trails and walkways, but more money paralleled another trend; that of annual appropriations for the park having almost doubled since 1925. It reached more than $62,000 in 1928, a figure meant to cover maintenance costs, utilities, equipment, and staff salaries.62 Most of the money spent on trail maintenance that year still went toward opening Sparrow’s route to the lakeshore, just as work proceeded on finishing its replacement. Thomson, meanwhile, saw a need to “recondition” several other trails now that most had been in use for a decade. Without more funding dedicated to maintenance, however, their condition could deteriorate to a point where a full or partial reconstruction became necessary.63

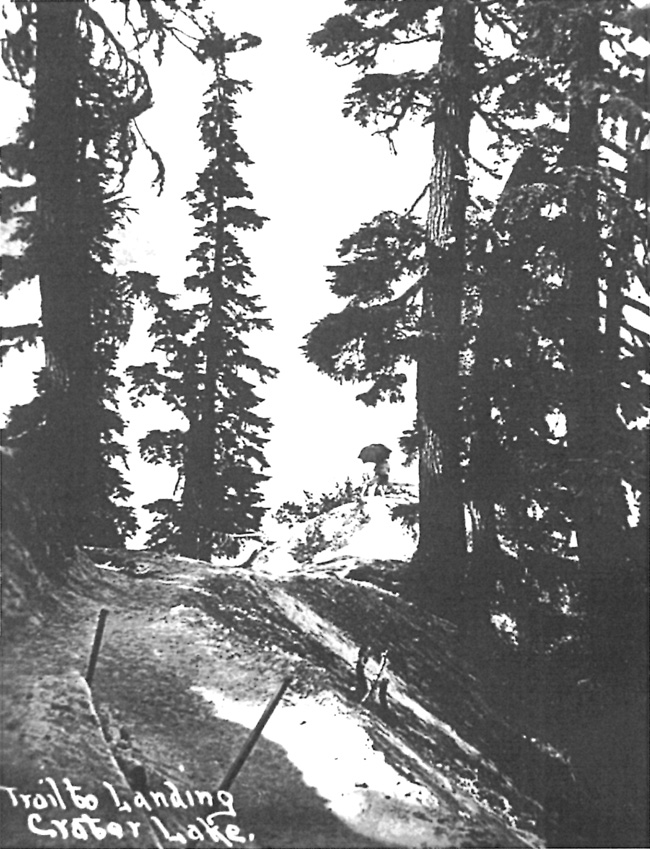

|

| A section of the Sparrow Trail in the 1920s. Photo by Frank Patterson, author’s files. |