Introduction

It is fair to say that trails in Crater Lake National Park have received far less attention as circulation devices than roads. There are numerous reasons for this, not least being the distances required for visitors to reach the park and costs associated with ensuring safe vehicular travel. Yet trails can be as central to experiencing the park or more so, especially since they require travel by foot, horseback, and (when covered by snow) skis or snowshoes. Their origin, construction, and use is the subject of this paper, one aimed at providing background and context for how these circulation features were developed over the course of more than a century.

Generalizing about any “system” of trails can be difficult because the term trail has numerous meanings. In this case, trails are separated into four broad categories, beginning with those that are or were beaten paths with few efforts made to improve and maintain them for use by pedestrians or horses. Second, some trails exist with minimal location work, but have been marked by blazes, tags on trees, or signs and receive use that includes skiing and snowshoeing. The third category is limited to roads originally constructed for wagons or automobiles, but subsequent use has been limited to pedestrians and stock. The fourth category of recreational trails usually exhibit engineered qualities that in many respects make them somewhat akin to highways designed for foot travel.

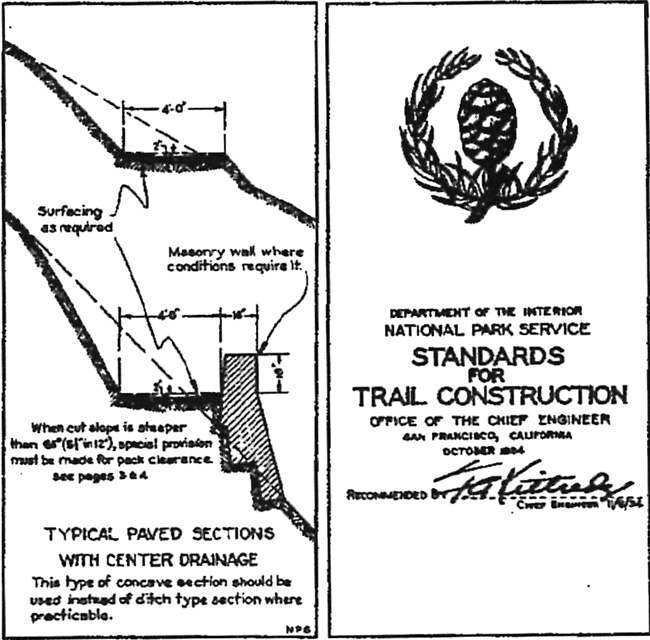

There is some overlap between categories, since some trails at Crater Lake can fit into more than one, but they provide a starting point for describing the intent of their builders, methods of construction, and subsequent realignments. Recreational trails can be further subdivided into the front- and back-country types, but even within these designations, there is often considerable variation in what can be called typical sections. It is probably safer to say that recreational trails tend to follow established standards for width, grade, curvature, and drainage features. Whether intended for pedestrians and/or stock, location work preceded their construction, and in the best examples, trail building reflected the principles expressed in the NPS standards of 1934.1

|

| Excerpts from the NPS Standards for Trail Construction, 1934. Courtesy of Electronic Technical Information Center, Denver. |

Previous documentation, notably in the second volume of an administrative history by Harlan Unrau and a historic resource study by Linda Greene, included trails as a minor component of their work relating to the development of park infrastructure. Apart from the problems associated with construction and maintenance of trails used to access the lakeshore, both accounts are largely limited to depicting the extent of park trails at selected points in time. What drove initial construction, much less changes, their maintenance, and in some cases, interpretation, has been overlooked and could prove useful to future planning efforts. So might a summary of trails that have faded into disuse and the reasons why some proposals for trails in the park did not come to fruition.