A small number of enrollees took on reconstructing the Castle Crest Wildflower Trail in 1938, a project that included several major changes to what had been built nine years earlier. The most conspicuous involved a new trailhead, now that contractors were grading the last section of Rim Drive. Enrollees moved the trailhead to a new parking area located along the road, but also obliterated several confusing cross trails and moved a telephone line that had formerly crossed the “garden.” They repaired log footbridges, built rock steps in several spots, and placed larger flagstones where the trail crossed wet ground.117

|

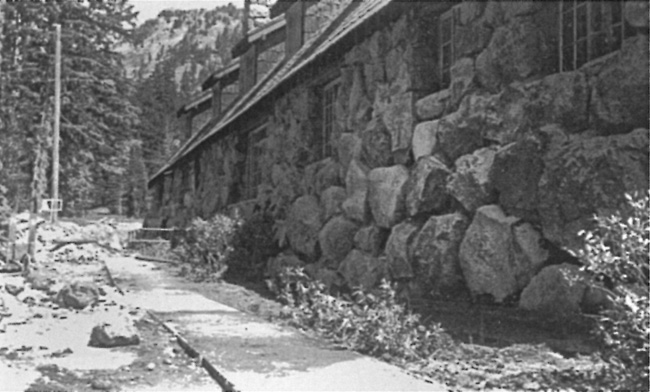

| Walkway at rear of the Ranger Dormitory, 1937. NPS photo by Francis G. Lange in the National Archives, San Bruno, California. |

Funding and enrollment in the CCC had declined to where one of the two camps in the park was eliminated for the 1939 working season. Just as before, priorities for trails consisted of opening the Crater Wall Trail and maintaining the most heavily used routes, but enrollees did not undertake any new construction. They instead placed a wooden footbridge across a small stream near the Lady of the Woods and a virtually identical structure over Munson Creek between the Ranger Dormitory and three employee residences located above the dormitory. Enrollees also continued with a project started in 1937, which involved replacing metal signs with hand carved markers designed by Lange at various places frequented by visitors. Included in the program were signs at trailheads such as those for Lady of the Woods and Mount Scott.118

|

| Footbridge across Munson Creek, Park Headquarters. NPS photo by Francis G. Lange in the National Archives, San Bruno, California. |

Another trail sign came into existence once the NPS and USFS agreed on how to indicate a change in jurisdiction where the Oregon Skyline Trail crossed into the park from the Rogue River National Forest. This did not mean that a viable trail traversed the park, even if the NPS publicly supported the idea of a larger route extending from the Columbia River to the California state line. Although the initial concept of a Skyline route in 1920 had more to do with a road connection between Mount Hood and Crater Lake, Forest Service personnel worked steadily throughout the following two decades to build and connect trail segments in the high Cascades. A small band of outside supporters liked the idea and helped the Forest Service publicize the Oregon Skyline Trail with maps and leaflets, but they also began to think in terms of a backcountry route only available to hikers and equestrians that might link the border with Canada to the one shared with Mexico.119