|

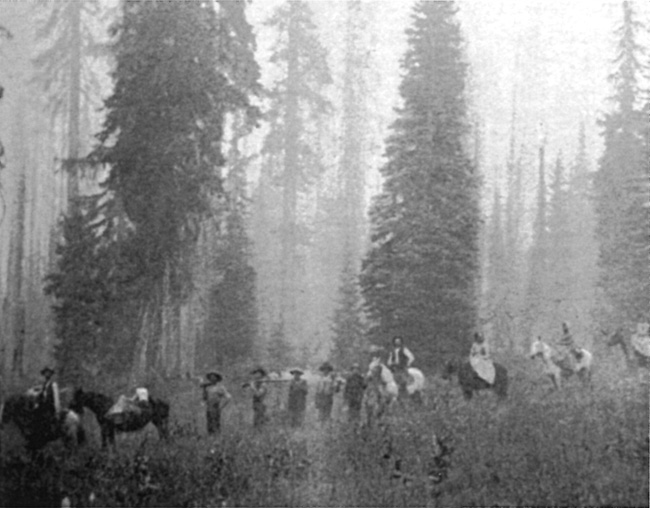

| Nineteenth century travelers making their way to Huckleberry Mountain. Photo credited to Ramona Hanks in Klamath Echoes (Klamath Falls: Klamath County Historical Society, 1968), 93. |

Opening of the wagon road in 1865 eventually induced a party of visitors from Jacksonville to mark a route by blazing trees from a point on the road near Dutton Creek about two miles to the rim of Crater Lake. The blazed track discouraged travel by wagon at first due to the steep and rough terrain, but had been improved enough to be called a “road” in visitor accounts from the 1890s.5Nevertheless, many camping parties chose to remain along Dutton Creek due to the availability of water, something largely absent at the rim, and then walked to see Crater Lake. Visitors used a path to the lakeshore from the rim by 1890, though more than one account described the precipitous descent from the future site of Crater Lake Lodge as hazardous, not least due to the high likelihood of rockfall.6

Having a safe trail to the lakeshore became a management concern upon the appointment of William F. Arant as the park’s first superintendent in the summer of 1902. The path necessitated a dangerous descent of 900 feet to Eagle Cove, so Arant requested $500 for improvements beginning in 1903.7 He reiterated the request, which included a cable for visitors to use in the most ominous section, in subsequent annual reports. No substantial improvements to its condition came until 1910, when a survey party from the Army Corps of Engineers made some changes in its location. As a small construction crew began work that autumn, they added switchbacks to lessen the grade and widen the route where possible. It still required what Arant described as “considerable repair work” each year due to annual washouts and other damage caused by rain and melting snow.8

|

| Visitors in the “Lower Campground” near Dutton Creek about 1900. Photo by Peter Britt, courtesy of the Southern Oregon Historical Society. |

As part of conducting the earliest scientific work at Crater Lake, J.S. Diller of the U.S. Geological Survey also compiled the first topographic map (in 1896) of what Congress would later designate as the national park. This fixed the park’s boundaries in 1902, but as an aid to visitors who wanted to see important geological features, he promoted a pack trip around the rim. Depicted and described as a circuit as early as 1897, Diller noted five years later there was no trail yet in existence for those who wished to follow the route.9 Instead, the closest approximation to any piece of the route started where the “road” blazed in 1869 terminated at the rim. The boundary survey of 1903 described the path as leading west from there to the “foot” of the Watchman, past Glacier (Hillman) Peak and then north/northeast to Diamond Lake.10 Located some 400 feet in elevation above Diller’s suggested pack route, Arant described the path as “not so much used.” He called for its improvement as early as 1906, recommending that a “good trail” could lead from the informal campground (at what later became Rim Village) to the summit of Hillman Peak, estimating that an appropriation of $200 would be needed for the work.11