Conclusion

This paper has attempted to show how engineered recreational trails (as opposed to those that can be characterized as blazed paths, beaten tracks, motorways, abandoned roads, or ski trails) struggled to become the dominant means used to convey pedestrians at Crater Lake from a trailhead to a terminal point. Even with new construction or extensive reroutes of recent vintage, they still constitute less than a quarter of all mileage signed as trails in the park. One of the main reasons stemmed from the beginning of NPS administration in 1917, when the line between roads and trails blurred, though the road system in the park eventually fit rather neatly into a classic hierarchy of circuit, approach, secondary, and service routes.220 There is no comparable way to organize trails at Crater Lake, mainly because an ad hoc approach (that is, for a particular purpose) has dominated planning for these facilities instead of one based on park-wide goals for recreational access, interpretive values, or causes such as wilderness preservation. The trails could certainly be classified according to shape (such as a loop, line, or horseshoe), or use (hiking, equestrian, or both), but they made no sense as a system if the motorways or old Rim Road were removed as maintained “trails.” Were that to occur, what might result bears no resemblance to the Sky Lakes Wilderness or Oregon Caves National Monument, where there are obvious trunk, branch, and feeder trails.

|

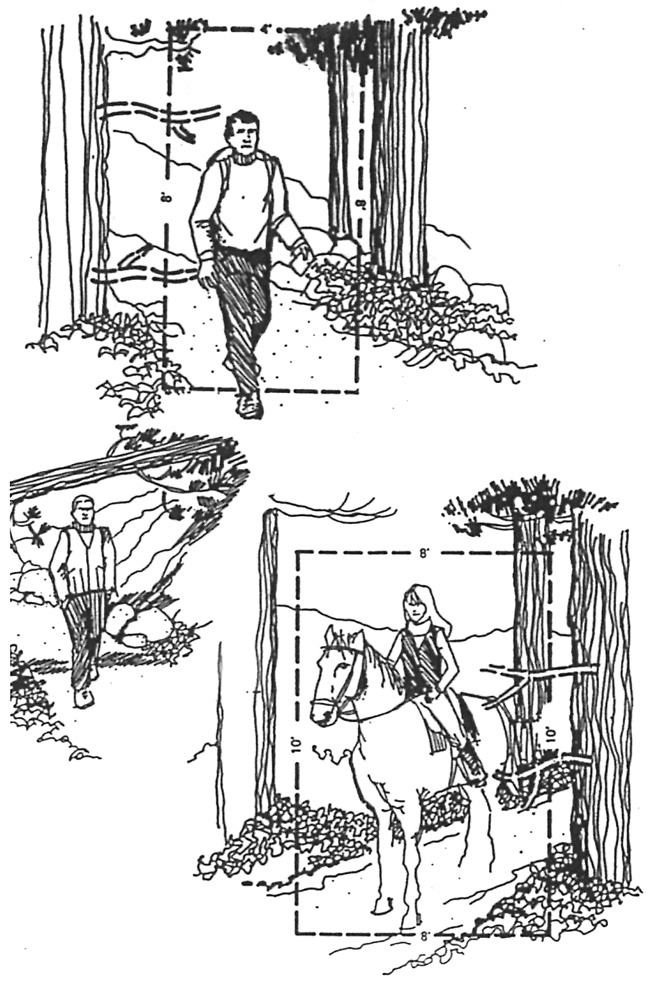

| Illustrations for trail standards adopted at Crater Lake National Park, author’s files. |

The routes labeled as trails (or, more broadly, part of pedestrian circulation) still fit within eight categories: lakeshore access, viewpoints above the lake, walkways adjacent to paved roads, short loops, routes directed to specific backcountry destinations, bridle paths, motorways or fire roads, and abandoned segments of circuit or approach roads. Some components of pedestrian circulation comprising this “envelope” are still missing or hardly evident in a park of more than 180,000 acres and five thousand feet of relief. Perhaps the most obvious is a “low elevation” trail allowing visitors to hike during June and much of July while snow is still melting on higher ground. Another omission is the lack of loops exceeding two miles in length, apart from several fire roads (which, of course, were not built as pedestrian routes). Even with the walkways included, there are very few parts of the park’s pedestrian circulation features that are universally accessible, while many of its most intriguing features can only be reached by hiking cross country in order to reach them.