Postcards from the camps

Herald and News

Klamath Falls, Oregon

April 25, 2005

Lumberjacks eat in a mess tent at the McCloud River Lumber Company around 1905. Lumberjacks eat in a mess tent at the McCloud River Lumber Company around 1905. |

Excellent photographers are a Klamath Basin tradition.

It’s a heritage that goes back to Peter Britt, who lived in Jacksonville but made the first images of Crater Lake that helped stir interest in making it a national park.

That photographic tradition continued with Fred Kiser, whose reputation as a

photographer was largely due to his own images of Crater Lake, often from viewpoints that made good use of his mountaineering skills. The current Rim Village Visitor Center is Kiser’s former photo studio.

And then there’s Charles R. Miller.

Five locomotives push a wedge plow to clear the tracks in January 1914. Five locomotives push a wedge plow to clear the tracks in January 1914. |

Miller, a contemporary of Kiser, was 27 when he moved from Portland to the Mt. Shasta City area. In the years that followed, Miller became one of the region’s best known photographers, especially at logging camps. He later moved to Klamath Falls, formed the Miller Post Card Company and had exclusive rights for scenic photographs at Crater Lake.

More than 160 black and white images taken between 1900 and 1915 are featured in “Mt. Shasta Camera: The Photographs of Charles R. Miller,” by Wayne Bonnett, $45, a beautiful coffee table book from Windgate Press.

Most of Miller’s artfully composed, richly textured images were taken in far Northern California lumber camps and mill towns. Included are photos of logging railroads and steam locomotives, log trains on precarious bridges, and engines pushing snow and steaming through primitive logging camps.

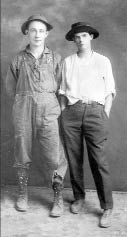

Charlie Linton and Frank Gibson have their portrait taken by Miller around 1906. Charlie Linton and Frank Gibson have their portrait taken by Miller around 1906. |

Other images feature sturdy, proud men, and sometimes young boys, at work. They’re sometimes lost in seas of mammoth logs, dwarfed by ancient machinery, or seated on benches at a logging camp mess tent.

Miller moved to Klamath Falls in 1909 and opened a Main Street studio. His postcards featured hunting, fishing and rodeo cowboys. Miller was granted Crater Lake photo privileges in 1913 and had exclusive rights in 1915.

Changing times forced him to find new sources of income. As Bonnett writes, “Simple, affordable Kodak cameras plus the automobile meant ordinary people, his customers, could travel and take pictures of their own.”

Miller ran the Orpheus Theater in Klamath Falls for two years, then apparently disappeared. Bonnett speculates the death of Miller’s 15-year-old son, Arthur, was a factor. Miller resurfaced in 1925 as manager of White Pine Molding Company, where he worked until his death in 1934. He is buried in the Linkville Cemetery.

“Miller’s photo postcards circulated for decades and today are sought after by collectors,” Bonnett writes. “His original photographs and albums found their way over time into private collections, museums and libraries. These surviving photographs, though relatively few, are Charles Miller’s legacy.”

Other pages in this section