Pine Beetles Infest Crater Lake Rim

Mail Tribune

Medford, Oregon

August 11, 2007

BY PAUL FATTIG

Warming is probably the cause of the insects’ proliferation

Global warming is the prime suspect in a mountain pine beetle infestation that is killing the whitebark pine trees on the rim of Crater Lake.

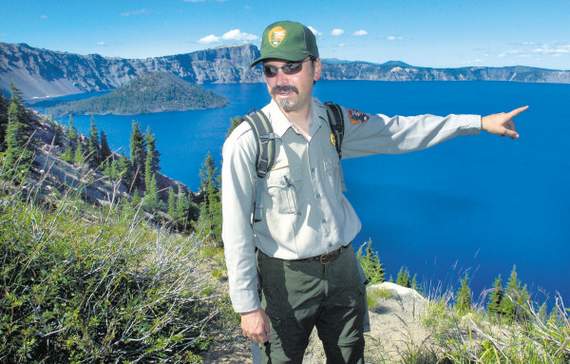

Already ravaged for years by white pine blister rust, the high-elevation trees began succumbing to the ordinarily lower elevation bugs in 2003, said Michael Murray, 41, terrestrial ecologist at Crater Lake National Park.

|

| Michael Murray, a Crater Lake ecologist, says there are no trees to replace the higher elevation pines destroyed by the beetles. Photo by Jim Craven 8/8/2007 |

“Mountain pine beetles don’t like cold winters,” he said of the park, which has averaged 44 feet of snow a year. “But they do like long summers, and we’ve been seeing warmer temperatures here.

“Some researchers have already concluded that global climate warming is responsible for increased activity of mountain pine beetles in high-elevation trees,” he added. “Global warming is the leading culprit.”

But he cautioned that as a scientist he would stop short of convicting it, pending further research.

However, since 1983, summer surface water temperatures at the nation’s deepest lake have risen 1.1 degrees per decade, according to park records. Summer nighttime air temperatures at the park reflect a similar increase.

Other forest ecologists Murray has talked to are witnessing a similar phenomenon.

“They are seeing more beetles in the high elevations than they’ve ever seen before and in places they’ve never been seen before,” said Murray, who has a doctorate in forest ecology. “In British Columbia and Alberta, mountain pine beetles are showing up farther north than they’ve ever been seen before.”

The park’s infestation reflects a scenario being reported at other forests throughout the West, said Dominick DellaSala, a forest ecologist and executive director of the National Center for Conservation Science & Policy in Ashland.

“It’s not unusual that insects kill trees,” he said, adding that trees stressed by dehydration and higher temperatures release chemicals that attract beetles.

“They pick up on the turpines released by stressed trees and gang up on the sick and dying ones,” he said. “They are doing their job of cleansing the sick in the forest.”

Because of the warming climate, beetles are able to multiply faster and invade in greater numbers, making them a greater threat to forests, he said.

Conifer trees in the Sierra Nevada Mountains are dying at nearly double the rate as they were two decades ago, stressed by hotter temperatures and lower precipitation, according to a U.S. Geological Survey study released Friday. The study, the result of a 22-year study on conifer trees in Yosemite and Sequoia national parks, showed that air temperatures in the study area had warmed by 1.8 degrees.

Murray has been monitoring the altitude advance of the pine beetles since he arrived at the park six years ago. Hailing from upstate New York, he previously worked on a spruce bark beetle infestation in Wrangell Saint Elias National Park in Alaska.

One large whitebark pine near the Rim Village that Murray estimated to be about 400 years old was killed by the beetles in the last two years.

“The (mountain pine) beetles started showing up about four years ago at the higher elevations,” he said of the native insect. “By two years ago, they had outpaced the white pine blister rust in infecting and killing whitebark pine in the park.”

Up to 20 percent of the susceptible pines on the west side of the park are infected with the blister rust, an airborne pathogen that arrived in the Pacific Northwest from Eurasia around 1910, he said. However, park employees have located 30 trees that appear to be resistant to the blister rust, he said.

Whitebark pines are found beginning at about 6,800 feet elevation in the southern Cascades, becoming the dominant species from about 8,000 feet and up, he said. The rim is around 7,000 feet with peaks jutting above 8,000 feet.

“The pine is special because it grows in the highest elevations of tree growth in the United States,” he explained. “That means it tends to live in places that are too harsh in terms of weather to any other tree species.

“You wouldn’t have a forest here at all if it weren’t for whitebark pine,” he added, speaking of the lake rim.

In addition to being a picturesque tree that tourists invariably include when they shoot a picture of the famous lake, whitebark pines are also a “keystone” species which other plants and animals depend on for survival, he said.

Clark’s nutcracker, a bird found only in the high elevations, relies on the seeds. Golden-mantled ground squirrels bury the cones, which can hold up to 100 seeds, as a winter food cache.

Last year, Murray discovered black bear scat in the park that appeared to contain remnants of the seeds. A subsequent laboratory analysis confirmed his suspicions, marking the first time it has been conclusively demonstrated that black bear eat whitebark pine seeds in the Cascade Range.

A beetle epidemic invaded the park in the 1920s and ’30s, but it was at a lower elevation, Murray said.

“The interesting dynamic with that is in the past, based on historic records, it would be the lodgepole (pine) stands that would get the heavy mortality, then you would have some mountain pine beetle filtering up into the whitebark pine,” he said. “This epidemic is different because it showed up into the whitebark pines first, and now we’re starting to see it showing up in the lodgepole pine.”

But the park service is employing a new weapon against the invasion. Murray has placed small packets of hormones called verbenone on the 30 trees that appear to be resistant to the blister rust. The synthetic chemical mimics a chemical created by the beetles that signals the other beetles that the tree is already full of beetles, he said.

“It’s a repellent,” he said, noting that results thus far show the packets are about 80 percent effective. “We’re fooling the beetles with this.”

Noting the centuries it takes for a large whitebark pine to grow on the rim, Murray hopes the hormones will ultimately halt the high-altitude beetle infestation.

“Dead trees are part of the natural cycle here but you don’t want them showing up all at the same time,” he said, adding, “These trees are irreplaceable.”

Reach reporter Paul Fattig at 776-4496 or at pfattig@mailtribune.com

Other pages in this section