Crater Lake National Park News

Crater Lake Institute – www.craterlakeinstitute.com

Beetle Outbreak Threatens Park Trees: Researchers Say Global Warming May be to Blame

Crater Lake Reflections

Crater Lake National Park

Summer/Fall 2008

National Park Service

Take a walk through Rim Village this summer and you will notice several things: fantastic views, smiling park visitors, and-from one end of the village to the other–dead pine trees. The dead trees are obvious, but the cause of the death may not be. A tiny beetle, rarely seen, is responsible for most of the damage. Scientists indicate, however, that the real culprit may be our warming climate.

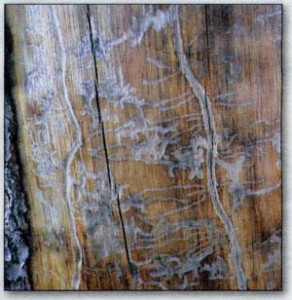

Beetles are attacking the park’s whitebark pine trees in increasing numbers. Larvae tunnel through the inner bark, killing the trees. Photo by Dion Manastyrski Beetles are attacking the park’s whitebark pine trees in increasing numbers. Larvae tunnel through the inner bark, killing the trees. Photo by Dion Manastyrski |

The mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae) is a native insect that goes unnoticed by even the most observant of us. It spends almost its entire life hidden beneath the bark of pine trees. Beetle larvae feed in the phloem tissue, or inner bark, of their hosts. This activity damages the phloem layer, cutting off the flow of nutrients and water. The trees literally starve to death. As the trees dies, their needles discolor, turning red.

According to park ecologist Dr. Michael Murray, mountain pine beetles have thrived in the forests of western North America for millennia. Usually, they occur in low numbers, but when environmental conditions are favorable, their populations explode. The last outbreak at Crater Lake was in 1923. By the time it ended around 1930, thousands of acres of lodgepole pines had been killed. The current outbreak began in 2003. “Right now,” reports Murray, “we’re in the midst of a moderate epidemic.”

Unfortunately, the current epidemic has a new-and disturbing-twist. “The beetles have found a new favorite target,” explains Murray. “They have turned their attention away from lodgepole pines and toward our majestic whitebark pines.”

Whitebark pines are a “keystone” species at Crater Lake National Park, critical to the survival of many other species of plants and animals. They are the only trees that grow at the park’s highest elevations, thereby anchoring the high-elevation forest community. The trees provide large, nutritious seeds for bears, squirrels, and birds.

So why have the beetles changed their diet? Murray explains: “Whitebark pines are well adapted to cold weather, whereas mountain pine beetles are not.” In the past, the insect’s intolerance of cold weather has generally safeguarded high-elevation forests. In 2003, however, when beetles began infesting whitebark pines in parks across the west, from Crater Lake to Yellowstone, scientists realized that what these diverse locations all shared was a warming climate. Because of global warming, it seems, beetles are now able to survive winter at higher elevations.

Early spring thaws also help beetles. In 2007, spurred by unusually warm temperatures, adult beetles were observed attacking trees in Rim Village during the third week of May-earlier in the season than ever before.

Mountain pine beetles spell double trouble for the whitebark pine, a species already under attack from a non-native fungus. The fungus, introduced from Eurasia, causes a fatal disease called “white pine blister rust.” Michael Murray’s research indicates that Crater Lake’s beetles are now outpacing white pine blister rust in a race to destroy these valuable trees.

While the park tries to combat the non-native fungus-a process that involves identifying disease-resistant trees and harvesting their seeds for eventual re-planting-a decision has been made to protect the whitebark pines at Rim Village from further beetle attack. In 2004, Michael Murray began stapling small packets to the trunks of the trees. The packets contain a non-toxic gel that mimics a hormone that mountain pine beetles emit to repel other beetles.

The future of whitebark pine communities at Crater Lake is uncertain. For now, park staff continue to seek an understanding of the complex interrelationships between beetles, high-elevation forests, and our warming climate.

Other pages in this section