Former National Park Service director George B. Hartzog Jr. dies

Crater Lake Institute

By ROBERT UTLEY (see below)

January 31, 2009

Former director of the National Park Service George B. Hartzog Jr., 86 [b. March 17, 1920], passed away June 27th, 2008, in McLean, Virginia. He had suffered failing physical health for several years but lost none of the mental powers for which he was noted. He is survived by his wife of sixty years, Helen, and three children: George III, Nancy, and Edward.

Hartzog served as director of the National Park Service from 1964 to 1972–years of national turmoil but years, also, that provided a political environment of extraordinary opportunity. President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall’s aggressive environmentalism, and a Democratic Congress receptive to the cause of the national parks conferred advantages that no director before or since has enjoyed. Hartzog possessed the bureaucratic and political talents to exploit this combination.

His most conspicuous achievement was expansion of the National Park System. During his nine-year directorate, the system grew by seventy-two units–not just national parks, but historical and archeological monuments and sites, recreation areas, seashores, riverways, and memorials–more than at any comparable period in its history.

Hartzog was especially proud of advancing workplace diversity. Under his guidance, the Service gained its first black park superintendent, its first career woman superintendent, its first Indian superintendent, and the first black chief of a major national police force. The Service took on a different public appearance as more women and minorities rose in the ranks to important positions.

He sought to bring park resources and values to urban populations. New York City’s Gateway and San Francisco’s Golden Gate national recreation areas took form during his tenure, and he spawned a host of environmental education programs that touched and inspired urban dwellers, especially inner city youth.

|

George B. Hartzog, Jr., as assistant superintendent of Rocky Mountain National Park, 1956. R. Taylor, photographer. (National Park Service Historic Photograph Collection, Harpers Ferry Center.) |

|

George Hartzog enjoys a fishing expedition, after 1972. (National Park Service Historic Photograph Collection, Harpers Ferry Center. |

Hartzog played a critical role in the passage and implementation of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, whose financial, registration, and protective features have saved structures, sites, and entire districts in every state and Indian tribal lands.

Of enormous consequence, working with Senator Alan Bible, Hartzog played a critical role in laying the legislative groundwork for the selection of “National Interest Lands” in Alaska. Ultimately, when finally enacted by the Congress, the park selections doubled the size of the National Park System.

Hartzog introduced programs and professional attitudes that made national parks more welcoming to people of color and different economic classes. Recognizing the encroachment of urban crime into the parks, he began the training of rangers in law enforcement.

Hartzog’s directorate ended abruptly in December 1972. President Richard Nixon, re-elected a month earlier to a second term, fired Hartzog. His political dexterity and intimate relationship with congressional barons discomfited the White House. Also, unknown to Hartzog, one of his superintendents had offended Nixon pal Bebe Rebozo. The vigorous appeals of Secretary of the Interior Rogers C. B. Morton failed to persuade the president to change his mind.

Hartzog told his story in a 1988 book,Battling for the National Parks.

Reared in poverty in rural South Carolina, George Hartzog absorbed the compassionate values of family, community, and church–he even became a lay preacher–and carried them with him to his death. Forced to support a family impoverished by a disabled father, he could pursue education only sporadically. With a high school diploma and a few months of college, he applied himself to reading law in the office of a local attorney. That enabled him to gain admission to the South Carolina bar in 1942.

After service in World War II as an army military police officer, Hartzog entered the ranks of government as an attorney and soon found a position in the National Park Service. He did both legal and concessions work in the Washington office and gained management experience as assistant superintendent of both Rocky Mountain and Great Smoky Mountains national parks.

|

Left to right: Newton B. Drury, Horace M. Albright, George B. Hartzog, Jr., Conrad L. Wirth. Director Hartzog gathers with three former directors at the dedication of the Stephen T. Mather Home in Connecticut, a Registered National Historic Landmark, July 17, 1964. Jack E. Boucher, photographer. (National Park Service Historic Photograph Collection, Harpers Ferry Center.) |

Beginning in 1959, Hartzog made his name as superintendent of Jefferson National Expansion Memorial on the St. Louis waterfront, a park that commemorates America’s westward expansion. Employing imaginative legal and contract stratagems, he surmounted daunting obstacles to revive the stalled construction of the massive arch, the creation of famed architect Eero Saarinen, that symbolized the gateway to the West.

Hartzog’s work in St. Louis and on the proposed Ozark National Scenic Riverways caught the attention of Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall. The Kennedy-Johnson administrations signaled major changes in the federal government, none more so than the National Park Service. The two presidents sought bold changes. Udall thought Hartzog would bring to the job a “new dynamism.” He became director early in 1964.

Parts of the entrenched bureaucracy disliked and feared the new director and his style. He prevailed with strong, decisive leadership–and a vision to take the national parks to places they had never gone. He was a workaholic and demanded the same from all who answered to him. He could be an abusive tyrant one moment, and a compassionate, caring friend the next. Whatever his mood of the moment, he cared deeply and personally about everyone in the National Park Service, and he let them know it.

Hartzog remained controversial throughout his directorate, both in and out of the National Park Service. But as his achievements multiplied and he emerged as incontestably brilliant, quick-minded, and impressively articulate, he amassed a loyal following that labored tirelessly to further his objectives.

|

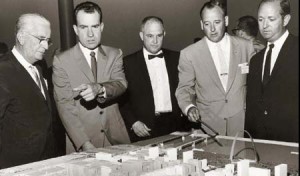

Left to right: St. Louis Mayor Ray Tucker, Vice President Richard M. Nixon, Congressman Tom Curtis, George B. Hartzog, Jr., Morton D. “Buster” May, Chair of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Association. Superintendent Hartzog points out proposed features of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, c. 1960. Harold Ferman, photographer. (National Park Service Historic Photograph Collection, Harpers Ferry Center.) |

For those who worked for Hartzog, even those discomfited by his frenetic pace of change, he is remembered as a great director. In fact, Robert Utley, who served as chief historian of the Service during the Hartzog era, speaks as a historian when he judges Hartzog the greatest director since the founding duo of Stephen Mather and Horace Albright in the years after passage of the National Park Service organic act of 1916.

Reflecting the apprehension with which field employees greeted the “new dynamism,” longtime Park Service deputy director Denis Galvin looked back on his early years: “I was a new park employee when George Hartzog became director. When the peripatetic director visited the park where I worked I found some vegetation to hide behind. I still wound up in New York City as part of his urban parks program. As usual, he was right.”

Famed writer Wallace Stegner captured the essence of the man he came to know so well: Hartzog was the “toughest, savviest, and most effective bureau chief who ever operated in that political alligator hole. . . . Among distinguished public administrators he was one of he most distinguished, one of the friendliest, and one of the most honest.”

And as retired historian William E. Brown lamented: “How far we have fallen and how we will miss his voice. We’ll just have to soldier on and carry his inspiration with us.”

|

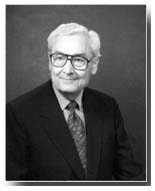

George B. Hartzog, Jr., at the National Park Foundation Board meeting, Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia, 1972. Cecil W. Stoughton, photographer. (National Park Service Historic Photograph Collection, Harpers Ferry Center.) |

Webmaster’s Note: A special thanks to Bob Utley for allowing the Crater Lake Institute to post this write-up. Thanks Bob!

Robert Utley is an author and historian who has written sixteen books on the history of the American West, including The Lance and the Shield: The Life of Sitting Bull. He was a former chief historian of the National Park Service. Fellow historians commend Utley as the finest historian of the American frontier in the 19th century.The Western History Association annually gives out the Robert M. Utley Book Award for the best book published on the military history of the frontier and western North America (including Mexico and Canada) from prehistory through the twentieth century.Utley lives in Georgetown, Texas, with his wife Melody Webb, also a historian. |

Other pages in this section