Originally published by Steve Mark, Crater Lake NP historian

Republished here from the Sierra Club history vault

Seventeen Years to Success:

John Muir, William Gladstone Steel, and the Creation of Yosemite and Crater Lake National Parks

By Stephen R. Mark, Historian, Crater Lake National Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior

Chronology of William Steel’ s life.

Over the past century, activists have done much to stimulate legislative action for national parks and equivalent reserves. Their efforts have been a key factor in the National Park System’s continued expansion, particularly with respect to natural areas located in the western conterminous United States.(1) Great Basin National Park is the most recent example of this, having been established in Nevada during 1987.

In 1988, Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument and City of Rocks National Reserve were established in Idaho. Like the Great Basin proposal, these units were created through the efforts of one activist.(2) This is hardly a new phenomena, because many of the oldest park units were the result of one-man efforts. Examples include Sequoia (1890), Crater Lake (1902) and Rocky Mountain (1915).

Campaigns for Sequoia and Rocky Mountain were comparatively short (seven years each), in contrast to the 17 years it took to obtain effective designation for Yosemite and Crater Lake. In comparing Muir’s campaign to place Yosemite Valley under national park administration with Steel’s effort to establish Crater Lake National Park, there are some broad similarities. Each man won deceptively easy battles soon after becoming an activist but found their larger goals more elusive. Besides framing their proposals similarly, they shared some methods still employed by modern park proponents. And like some of their modern counterparts, Muir and Steel were also able to adapt to changing political circumstances to finally achieve their aims.

John Muir (1838-1914) has become an international figure whose stature is related to the impact of his writings upon the conservation movement. After coming to California in 1868, he worked at various seasonal jobs in the Sierra Nevada before making a name for himself in the early 1870s as a writer. Although Muir mentioned national parks and preservation of forests in his early writings, he did not become an activist until 1889.(3)

The turning point came when Muir and an editor named Robert Underwood Johnson embarked upon a camping trip to Yosemite in 1889. On the second night of the trip, they sat in front of a campfire planning a campaign that would alter Muir’s life and the face of Yosemite. As Johnson later recalled:

It was at our campfire at the Tuolumne fall at the head of the canon that Muir let himself go in whimsical denunciation of the commissioners [appointed by the State of California to manage the state park in Yosemite Valley] who were doing so much to make ducks and drakes of the less rugged beauty of the Yosemite by ill-judged cutting and trimming of trees, arbitrary slashing of vistas, tolerating of pig-sties, and making room for hay-fields by cutting down laurels and under brush–the units by which the eye is enabled, in going from lower to higher and stir, higher trees, ultimately to get adequate grandeur of cliffs nearly three thousand feet high. It is an old scandal, and I only refer to it now because it was at this campfire that a practical beginning was made of a campaign which, after fifteen years, by the recent act of recession of the Valley to the United States, we may confidently hope has ended an era of ignorant mismanagement.(4)

Two superbly-timed magazine articles written by Muir for Johnson’s Century Magazine greatly aided passage of a bill creating a two million acre forest reservation. in the Yosemite region on October 1, 1890.(5) Yosemite Valley, however, remained under state control while the “forest reservation” became known as Yosemite National Park. Not until June 11, 1906, did Muir and Johnson realize the goal of getting the valley and surrounding national park under the unified administration of the federal government.

To frame his proposal, Muir had to summarize how he would address the problem of park management in Yosemite Valley. He did this by centering on three main points, the first being that the valley was explicitly a national, not state, concern. Muir believed the federal government had the ability to provide more permanent improvements and policies than did the state through its appointed commissioners. Federal control would lead to increased appropriations for roads, trails, and utilities which would facilitate greater tourist travel. The federal authorities would also be in an economically disinterested position. This would increase the chances that appropriate development would be coordinated by a landscape architect.(6)

The second part of Muir’s proposal was that resident authorities must have sufficient power to protect the entire park area. Galen Clark had been appointed guardian to the valley, but he had no assistants, little money for administration, and was under the orders of commissioners who were often motivated by political considerations. Muir preferred the use of the U.S. Army to guard Yosemite Valley and the backcountry from trespass by sheep, damage caused by careless campers, and the effects of forest fires. The latter was to prove especially troublesome under two jurisdictions because their representatives could not agree over who should pay for fire protection.

Muir’s third point was that recession of the valley — ceding from state ownership back to the federal government — was tied to protecting surrounding forests whose primary importance was conservation of water supplies. He used the water supply argument to lobby against the Caminetti bill of 1895 which would have reduced Yosemite National Park by half and severely damaged the recession campaign.(7) Muir’s opposition to the bill also stemmed from the belief that the newly created federal forest reserves (which were later to become national forests) should not be compromised by inholdings. During this period thousands of acres of formerly public domain forest land slipped into private hands, often by fraudulent means. Once the timber was cut, there were aesthetic problems and difficulties in maintaining enough water for irrigation and municipal supplies. Without federal control, he saw the infamous “stump forest” in Yosemite Valley being duplicated on a larger scale throughout the Sierra.(8)

The components of Muir’s campaign matched those of Steel’s, though the beginning of the Crater Lake effort predated attempts at Yosemite recession. William Gladstone Steel (1854-1934), like Muir, enjoyed something of an early victory by seeing ten townships around Crater Lake reserved from settlement in 1886. This was done as a necessary first step in the creation of a national park, but soon encountered the reluctance of many congressmen who viewed such reservations as a drain on the Treasury.

Born in Ohio, Steel finished high school in Portland, Oregon. He became a postal carrier after short stints as a newspaperman, railroad promoter, and publisher. His first visit to Crater Lake came on a short vacation from the Portland post office in 1885. Steel and a friend went to southern Oregon to meet up with geologist Joseph LeConte who was studying the volcanic features of the Pacific Coast. After seeing the lake for the first time, Steel wrote:

Not a foot of the land about the lake had been touched or claimed. An overmastering conviction came to me that this wonderful spot must be saved, wild and beautiful, just as it was, for all future generations, and that it was up to me to do something. I then and there had the impression that in some way, I didn’t know how, the lake ought to become a National Park. I was so burdened with the idea that I was distressed. [For] Many hours in Captain Dutton’s tent [Dutton was head of a small military party assigned to accompany LeConte], we talked of plans to save the lake from private exploitation. We discussed its wonders, mystery and inspiring beauty, its forests and strange lava structure. The captain agreed with the idea that something ought to be done–and done at once if the lake was to be saved, and that it should be made a National Park.(9)

Upon returning to Portland, Steel began circulating a petition that eventually found its way to the state legislature. It was favorably received and a resolution recommending a public park around Crater Lake was forwarded to the Secretary of the Interior Lucius Q.C. Lamar. As a result, ten townships were withdrawn from entry by executive order of President Grover Cleveland on February 1, 1886.(10)

Like Muir, Steel contended that his proposal was of national concern. He did not support LeConte’s view that efforts to establish a state park at Crater Lake might be more fruitful.(11)Steel was convinced that Oregon could not afford proper maintenance and protection of Crater Lake, so he opposed the state park bills introduced to Congress in 1889, 1891, and 1893.(12)

Provision was made in Steel’s proposal for enforcement of the regulations by resident authorities. Uppermost in his mind was the damage caused by sheep. Their trampling had so destroyed the area’s vegetation in the years before the park was established that the result could still be seen in the 1930s. Fires, whether started by lightning or sheepmen, were another nemesis which Steel wanted controlled.(13)

The park proposal was also tied to the larger goal of protecting forests in Oregon’s Cascade Range. As with the Sierra, the primary justification for their retention in public ownership was water supply. Steel fought for the establishment of a 300-mile-long forest reserve stretching from the Columbia River to the California border. This was proclaimed by President Cleveland in 1893 and included the Crater Lake reservation. The Cascade Forest Reserve was the largest in the nation and was subsequently attacked by sheepmen and timber speculators.(14) Steel and a state supreme court justice named John Waldo (both of whom envisioned a reserve managed much like a national park) worked to defend it throughout the 1890s.(15)

TACTICS USED BY MUIR AND STEEL

Once the components of the Yosemite and Crater Lake proposals had been formulated, Muir and Steel used some remarkably similar methods to achieve their aims. Although the two men were only acquaintances, they did have common interests and were in intermittent contact from 1888 to 1912.(16) This would explain some of the similarities, particularly with respect to the development and use of constituencies to back their proposals.

Both Muir and Steel obtained early local support, something that sustained them throughout their campaigns. The major cities of their respective states furnished each man’s base of support: Muir in San Francisco and Steel in Portland. Having already emerged as a literary figure, Muir had many powerful friends in California who could provide him with introductions to useful contacts. Likewise, Steel was well-situated within Oregon’s Republican Party and had two brothers who were Portland financiers. Each man received the support of their states’ major newspapers early in their campaigns. This move proved useful when sheep and timber interests tried to dismantle Yosemite National Park and the Cascade Forest Reserve. They also gave public lectures as a way to enhance their proposals’ credibility. The fact that each man was a renowned climber and participant in the scientific study of mountain areas helped attendance.(17)

Both men started their campaigns by writing articles in literary magazines. Muir had a national audience while Steel’s notoriety remained largely regional.(18) Nevertheless, Steel was the first to write a book that he could use to promote his proposal. The Mountains of Oregon was published in 1890 as a loosely-organized anthology of articles on mountaineering and proposed parks. Steel highlighted the longest piece, one about Crater Lake, when he mailed copies of the book to congressmen and other federal officials. The book’s title is interesting in light of an acknowledgment that Muir wrote to Steel after receiving a copy:

I thank you for a copy of your little book The Mountains of Oregon + congratulate you on the success with which you have brought together in handsome shape so much interesting + novel mountain material.

With pleasant memories of my meeting with you the year I was on Mt. Rainier.(19)

Muir’s The Mountains of California was published in 1894. Far more cohesive than Steel’s book (which was a hasty arrangement of material originally intended to be published in separate pamphlets), it enhanced Muir’s reputation among scientists and brought him critical acclaim from the public. With the Caminetti bill looming over Yosemite in 1895 and the forest reserves threatened by hostile interests, Muir began to intensify his literary efforts. Ten of his essays were published in the Atlantic Monthly starting in 1897 and later appeared as a book entitled Our National Parks in 1901.(20) Six of the ten pieces were devoted to Yosemite, while three others focused upon the fate of the forest reserves.

Both men found that groups organized to enjoy the outdoors could form a useful constituency. Steel predated Muir in this regard by organizing the Oregon Alpine Club on September 14, 1887. It was largely a social fraternity whose purpose was “to attract attention to the scenery of our [Pacific Northwest] mountain ranges.. By late 1892, the expense of a mountaineering museum had bankrupted the club and personally cost Steel $1,000. Membership had dwindled to less than a hundred and most observers thought the club was dead.(21)

Steel eventually realized that an active mountaineering club might have a longer life. On July 19, 1894, amid great local publicity, 193 climbers ascended Mount Hood and became the first Mazamas. According to Steel, one of the group’s aims was to make the Oregon Cascades famous and to sponsor regular outings.(22) After being elected its first president, Steel organized an outing to Crater Lake in August 1896. The group gave it wide publicity and supplied the event with an interesting touch by christening the mountain that contains the lake “Mazama.”(23)

The Sierra Club was organized May 25, 1892, and evolved from a proposal that R. U. Johnson made to Muir in 1889 regarding an “association for preserving California’s monuments and natural wonders.”(24) The public meetings in San Francisco were heavily attended at first and the club began publishing a regular bulletin. As president, Muir’s attendance at meetings was erratic so the organizing fell to other board members. Almost nonexistent by 1898, the club was revived when its new secretary William Colby sold the idea of sponsoring regular outings. The first was held from a base camp in Tuolumne Meadows in 1901 and was an immediate success. Aimed at attracting new members, the outings included organized hikes as well as natural history lectures by Muir and other club leaders.(25)

The differences between the Yosemite and Crater Lake proposals also shaped the way each group responded as a constituency. Muir aimed to provide better management for an area where there was substantial human impact, so the Sierra Club aimed at becoming a Yosemite Valley resident. As early as 1894, the Sierra Club’s board of directors wanted to establish a patrol system in the valley to help enforce state park regulations. This would be “the first step in the direction of preserving the Valley from the wanton destruction of visitors.”(26)

What evolved was an information bureau housed in a refurbished wood frame cottage in Yosemite Valley from 1898 to 1902. In 1903, the bureau was moved to the newly completed LeConte Memorial at the base of Glacier Point. The structure’s completion coincided with the chaos arising from a disastrous fire which burned from the Wawona Road to Glacier Point. This happened largely because the state commissioners and U.S. Army authorities could not agree who should fight the fire. The case for recession was further strengthened that summer when the state commissioners notified the transport companies not to allow more visitors to enter the valley until overcrowded conditions were relieved.(27)

The Mazamas’ response to its founder’s proposal was different because Steel wanted national park status for a feature little known to science. As a result, the group fostered scientific investigation at Crater Lake on one occasion and used the findings to promote the proposal. Although their involvement was largely peripheral, the Mazamas’ facilitation was important in allowing scientists to build upon what an earlier expedition had done at Crater Lake.

During the summer of 1886, the U.S. Geological Survey sounded the lake and mapped the area’s topography.(28) Much of its success was due to Steel, who, in his role as special assistant to the expedition, was responsible for transporting the boats and equipment. His role in the undertaking gave him credibility and allowed the Oregon Alpine Club to cosponsor the O’Neal Expedition of the Olympic Mountains in 1890. Another success followed so Steel felt confident in organizing an even larger undertaking, the Mazamas outing of 1896. By arranging the trip so that the Mazamas were climbing nearby Mount McLoughlin while scientists from various government bureaus made their investigations, he hoped to give the proposal both scientific merit and wide publicity. After their climb and an excursion to Wizard Island, the Mazamas assembled on a site overlooking Crater Lake so the findings could be presented.(29)The outing also allowed the scientists to meet with members of the National Forestry Commission, a body whose purpose was to make recommendations about the disposition of the forest reserves. For this to happen, Steel cut his participation in the Mazamas trip short so he could bring the commission to the lake less-than a week later.(30)

Neither Muir nor Steel were strangers to state and national politics by the time they finished their park campaigns. Both found ways to secure influence with businessmen, legislators, and government officials through various lobbying techniques. In addition, each man chose an unexpected intermediary when his proposal reached a crucial stage.

After years of petitions, testimonials, and localized legislative support, the proposals began to move toward realization when Theodore Roosevelt assumed the Presidency in 1901. It was Roosevelt’s influence that allowed the Crater Lake bill to come up for debate in the House of Representatives in April of 1902.(31) Muir’s most publicized lobbying for recession came when he and Roosevelt camped alone in Yosemite for three days in May 1903.(32) This led to the president’s intervention when Senate cooperation was needed to add the valley to Yosemite National Park in 1906.

Although Roosevelt was a key figure in the adoption of both proposals, Muir and Steel had to use unusual intermediaries before the President could sign either bill. In Muir’s case this proved to be E.H. Harriman, president of the Southern Pacific Railroad. Harriman made use of the railroad’s influence on the California state legislature after Muir and William Colby did some hard lobbying for recession. When the measure came up for a vote in February of 1905, nine crucial votes turned the tide and it passed. About a year later Harriman came to the rescue again when a joint resolution accepting the valley stalled in the House.(33)

Although Harriman’s actions can be explained largely by his friendship with Muir, the Southern Pacific also wanted control of transportation to Yosemite.(34) In spite of the railroad’s ulterior motive, Muir accepted Harriman’s assistance. He reasoned that federal control of the entire park area would lessen the destruction caused by the numerous concessioners (27 at the time of recession) and other entrenched interests. Furthermore, the Sierra Club’s board declared that Yosemite’s poorly-maintained toll roads and the valley’s substandard accommodations were hurting California’s economy.(35)

Steel’s intermediary was Gifford Pinchot. At first this seems strange, especially given the view that Pinchot’s name never appeared in connection with the promotion of national parks.(36) But he did seem to have been more enthusiastic about Crater Lake than Muir, whose writing about his visit in 1896 indicated that the most impressive feature of southern Oregon was its variety of tree species.(37) Pinchot camped with Muir at the lake and later wrote:

. . .we drove to Crater Lake, through the wonderful forests of the Cascade Range, while John Muir and Professor [William H.] Brewer made the journey short with talk worth crossing the continent to hear. Crater Lake seemed to me like a wonder of the world.(38)

A somewhat similar situation developed in February 1902 when Steel was eliciting testimonials for the bill which would establish Crater Lake National Park. Muir begged off in his response:

I don’t know the Crater Lake region well enough to answer the question “Why should a national park be established to include Crater Lake.”You know this region much better than I do. I should try to show forth its beauty + usefulness explaining its features in detail + pointing out those which are novel + which require Government care in their preservation etc. . .(39)

By contrast, Pinchot’s reply was ecstatic:

. . . You ask me why a national park should be established around Crater Lake. There are many reasons. In the first place, Crater Lake is one of the great natural wonders of this continent. Secondly, it is a famous resort for the people of Oregon and of other States, which can best be protected and managed in the form of a national park. Thirdly, since its chief value is for recreation and scenery and not for the production of timber, its use is distinctly that of a national park and not a forest reserve. Finally, in the present situation of affairs it could be more carefully guarded and protected as a park than as a reserve.(40)

The bill was passed unanimously by the committee but was opposed by the Speaker of the House who refused to let it be debated. He relented only after Pinchot had spoken to Roosevelt about the bill.(41) After it passed the Senate, Pinchot wrote Steel again:

. . You give me more thanks than my small share in getting the Crater Lake bill passed deserves, but I am sincerely glad it has got along so far. There is no doubt, in my judgment, that the President will sign it. . .(42)

Steel’s triumph came a week later on May 22, 1902 when Crater Lake became a national park. His ability to get along with Pinchot allowed the proposal to get over the final hurdle. This is in contrast to Muir who had severed all ties with the forester in 1897 over the issue of sheep in the forest reserves.

The best explanation for why Pinchot was willing to do Steel’s bidding might be common interest. Passage of the Crater Lake bill occurred three years before Pinchot created the U.S. Forest Service and stimulated transfer of the reserves from control by the Interior Department’s General Land Office to the Department of Agriculture. Steel started the first forestry organization in Oregon and had surveyed the Stehekin section of the Washington Reserve when Pinchot was “special forest agent” for Interior in 1897.(43) They shared a vehement dislike for the GLO’s administration of the reserves, and Steel had at one point begun to waver from his previous position on sheep.(44) It was only when Pinchot attempted to bring the national parks under Forest Service administration in 1904 that this coalition began to wither.

RAMIFICATIONS OF THE PARK CAMPAIGNS

Although Muir and Steel at last saw their proposals favorably received by Congress, neither park retained all of what Steel obtained in 1886 and Muir won in 1890. Crater Lake National Park was established without the adjoining Diamond Lake area which had been in the original reservation. The opposition generated by Pinchot’s Forest Service has been successful in stopping Diamond Lake’s incorporation into the park and all but two minor extensions.(45) Yosemite National Park was reduced by boundary changes in 1905, which allowed some notable giant sugar pines to pass into private ownership. The trees were restored to the park in 1939 over the objection of the Forest Service, but they seemed small compensation for the part Pinchot played in damming Hetch Hetchy.(46)

Perhaps the long campaigns waged by Muir and Steel also have a lesson. Park management continues to deal with problems that both men thought were going to be solved by enactment of their proposals. It may have saddened Muir to find the National Park Service having difficulty implementing its plan to reduce congestion in Yosemite Valley. A similar irony exists at Crater Lake where extensive research is being conducted to determine if a geothermal energy company’s drilling outside the park could affect the lake.

We owe an enormous debt to these two men and other activists who have seen their proposals added to the National Park System. They were willing, as few people have been, to carry a considerable burden for little material gain. In most cases (Muir is a notable exception) the reward of activists has been obscurity. Nonetheless, as Steel expressed it in 1930, there is an intangible satisfaction:

Plundering through this wilderness of sin and corruption, tasting of its wickedness, forgetting my duty to God and man, striving to catch bubbles of pleasure and the praise of men, guilty of many transgressions, I now look back on this my 76th birthday, and my heart bounds with joy and gladness, for I realize that I have been the cause of opening up this wonderful lake for the pleasure of mankind, millions of whom will come and enjoy a and unborn generations will profit by its glories. Money knows no charm like this and I am the favored one. Why should I not be happy?(47)

Acknowledgments: The author wishes to thank Mark Wagner, Maureen Briggs, Melanie Smith, and Kent Taylor for their assistance in the preparation of this paper. It was originally presented to the 43rd annual meeting of the California History Institute in Stockton, California.

NOTES

1. This growth has occurred in spite of some government officials expressing the view that this category was “rounded out” in 1940 by the establishment of Kings Canyon National Park in California. Over 40 sites are currently targeted by the National Parks and Conservation Association (a group that has lobbied Congress since 1919 to defend, promote, and improve the National Park System) as potential additions to the natural area branch of the System. Over half are in the western United States.

2. It took Ralph Starr Waite 25 years to see the Great Basin proposal accepted. In Idaho, Paul Fritz took considerably less time because there was less perceived conflict among other groups.

3. Edith J. Hadley in her PhD. dissertation, “John Muir’s Views of Nature and their Consequences” (Univ. of Wisconsin, 1956), states that Muir toyed with the idea of a national park at Yosemite as early as 1872. There is some indication that Muir was willing to take steps publicly to further the cause of forest conservation before he met with Johnson; J.D. Hooker to Muir, March 19, 1886, microfilm reel 19, Microfilm edition of the John Muir Papers, R.H. Limbaugh and K.E. Lewis eds. (Stockton, CA; University of Pacific, 1986).

4. R.U. Johnson, “Personal Impressions of John Muir,” Outlook 80 (June 3, 1905), 303-304.

5. Ibid., p. 304. The articles were: “The Treasures of Yosemite”, Century 40 (August 1890), 483-500; “Features of the Proposed Yosemite National Park,” Century 40 (September 1890), 656-667. Several open letters that Muir sent to Johnson may have also been a factor in the passage of legislation creating a Yosemite National Park; see the Sierra Club Bulletin 29 (October 1944), 45-49.

6. Muir quoted in “Proceedings of the Meeting of the Sierra Club,” November 23, 1895, in Sierra Club Bulletin 1:6 (May 1896), 271-284.

7. San Francisco Examiner, January 15, 1895, p. 9; also cited in William F. and Mamie B. Kimes’ John Muir: A Reading Bibliography, (Fresno, CA: Panorama West Books, 1986), 150.

8. The “stump forest” is referred to in “The Treasures of the Yosemite”, but the water supply argument is more fully developed in Muir’s “Hunting Big Redwoods”, Atlantic Monthly 88 (September 1901), 304-320. This is a point upon which Muir agreed with the utilitarians in the forestry movement; see Gifford Pinchot, A Primer of Forestry, Part II-Practical Forestry, USDA-Bureau of Forestry Bulletin No. 24, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1900), 87. The degree to which forests affect water supply was an important part of subsequent U.S. Forest Service research; see Raphael Zon, Forests and Water in the Light of Scientific Investigation(Washington: GPO, 1927).

9. Quoted in Harlan D. Unrau, Administrative History Crater Lake National Park, Oregon, USDI-National Park Service, (Denver: NPS, 1988), 27-28. Steel has a different account in “Crater Lake and How to See It”, The West Shore 12:3 (March 1886), 104-106; also “Crater Lake Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow,” Steel Points Junior 1:2 (August 1925), n.p.

10. Special Session, Oregon Legislature, “S.J.M. No. 5”, adopted November 18, 1885, Steel Letters, Box 1, Item 211, Museum Collection, Crater Lake National Park. Executive Order, February 1, 1886, Record Group 49 [General Land Office], Division R, Box 125, Rogue River file, National Archives, and “The President’s Order”, Steel Points, 1:2 (January 1907), 73.

11. LeConte to Steel, January 5, 1886, Steel Letters, Box 1, Item 210, Museum Collection, Crater Lake National Park. Dutton expressed similar thoughts upon going back to Washington, D.C.; Dutton to Steel, February 27, 1886, SL, Box 1, Item 195.

13. LeConte noted the effects of large fires on his 1885 trip to Crater Lake; Sierra Club Bulletin1:6 (May 1895), 269-270. Muir mentioned fire’s effect on the Crater Lake area in his journal entry of August 31, 1896; Linnie Marsh Wolfe, John and the Mountains: the Unpublished Journals of John Muir (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1938), 357.

14. The Cascade Forest Reserve consisted of 4,883,588 acres when it was proclaimed on September 28, 1893. Next in size was the Sierra FR which was established on February 14, 1893, and had 4,096,000 acres.

15. An 18 page letter that Waldo wrote to the President on April 28, 1896, was probably the most eloquent defense of the reserve; a typescript copy of it is in the Oregon Historical Society Library, Portland. Steel also saw the Cascade Reserve as giving Crater Lake another layer of protection. Without its creation, he feared the possibility of the Crater Lake townships reserved in 1886 being restored to entry. An order by the Secretary of Interior was revoked for a brief time in 1890 at Sequoia before park proponents succeeded in getting national park designation for the Giant Forest and other groves; George W. Stewart to Col. John R. White, June 8, 1929, in Fry and White’s Big Trees (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1930), 26-27.

16. Their first meeting was in 1888 when Muir climbed Mount Rainier. Both of them attended the National Park Conference of 1912, held at Yosemite; see Proceedings (Washington: GPO, 1913).

17. Muir began giving public lectures in 1876 and throughout the next decade went to west coast cities to speak about glaciers, botany, and his travels. By the time he became an activist, he was a popular speaker whose income from other sources allowed him to be very selective. Steel’s career as a speaker began when he returned from Crater Lake in 1885 and broadened over time to include several lecturing trips across the country.

18. Although Muir began his literary career by mostly writing for newspapers, he found the national literary magazines not only paid better but were a more effective way of promoting his proposals; see Stephen Fox, John Muir and his Legacy: the American Conservation Movement(Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1981). Steel’s writings, by contrast, were generally newspaper articles whose distribution was limited to the Pacific Northwest.

19. Muir to Steel, October 2, 1892, SL, Box 1, Item 164.v

20. Originally published in Boston by Houghton-Mifflin; a reprint by the University of Wisconsin Press appeared in 1981.

21. Portland Oregonian, December 28, 1892 in Steel Scrapbook 9:1, Mazamas Library, Portland.

22. Medford (Oregon) Mail, September 27, 1895, in Steel Scrapbook 2:2, Museum Collection, Crater Lake National Park. Article II of the Mazamas’ constitution is precise: “The objects of this organization shall be the exploration of snow-peaks and other mountains, especially those of the Pacific Northwest; the collection of scientific knowledge and other data concerning the same; the encouragement of annual expeditions with the above objects in view; the preservation of the forests and other features of mountain scenery as far as possible in their natural beauty and the dissemination of knowledge concerning the beauty and grandeur of the mountain scenery of the Pacific Northwest.”

23. John D. Scott, We Climb High, A Chronology of the Mazamas 1894-1964 (Portland: Mazamas, 1969), 3. In 1895, Muir and LeConte were among the first three honorary members to be elected by the Mazamas.

24. Johnson to Muir, November 21, 1889, microfilm reel 6, Muir Papers, also cited in Fox, p. 106. The second issue of the Sierra Club Bulletin (June 1893, 31-39) showed that the club was interested in more than just California from the beginning. Club member Mark Kerr wrote an article about Crater Lake based on his experiences as topographer on the USGS expedition of 1886.

25. Linda Greene, Historic Resource Study, Yosemite National Park, (Denver: NPS, 1987), 355-356.

26. Elliott McAllister, “Report of the Board of Directors”, Sierra Club Bulletin 1:4 (May 1894).

27. Muir, et. al., “Statement Concerning the Proposed Recession of Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Big Tree Grove by the State of California to the United States,” Sierra Club Bulletin 5:3 (January 1905), 242-250.

28. “Report of Capt. C.E. Dutton,” Part 1, USGS Eighth Annual Report, 1886-1887, (Washington: GPO, 1887), 156-159; more detail is in his letters and scrapbooks held by Crater Lake National Park.

29. The scientists were J.S. Diller (USGS), Frederick Coville (Bureau of Plant Industry), C. Hart Merriam (Biological Survey), and Barton Evermann (U.S. Fish Commission); their papers were later published in Mazama 1:2 (October 1897), 161-238.

30. Steel later recalled that he had to walk from Crater Lake to Medford (some 85 miles in two days) so he could escort the commission back to the lake. Although the group recommended Mount Rainier and Grand Canyon for national park status, they failed to reach a consensus about whether to include Crater Lake. Its members were: Charles S. Sargent (Harvard University), William H. Brewer (Yale University), Arnold Hague (USGS), Henry S. Abbott (U.S. Engineer Corps), Alexander Agassiz (Coast and Geodetic Survey), Gifford Pinchot, and Muir.

31. Unrau, p. 100; Steel to Roosevelt, May 10, 1902, SL, Box 2, Item 11.

32. Muir, et. al., “Statement Concerning the Proposed Recession”, 245.

33. Harriman’s role in the recession is discussed in Fox, pp. 127-128. See also Richard J. Orsi, “Wilderness Saint and ‘Robber Baron’: The Anomalous Partnership of John Muir and the Southern Pacific Company for Preservation of Yosemite National Park”, Pacific Historian, 29:2/3 (Summer/Fall 1985), 136-156.

34. John Ise, Our National Park Policy, (Washington DC: Resources for the Future, 1961), 74.

35. Muir, et. al., “Statement Concerning the Proposed Recession”, 247.

37. Muir, “The National Parks and Forest Reservations,” Harpers Weekly 16:2111, (June 5, 1897), 566; “Forest Field Studies”, microfilm reel 28, Muir Papers; Wolfe, John of the Mountains, 356-357.

38. Breaking New Ground (New York: Harcourt Brace and Co., 1947), 101.

39. Muir to Steel, February 19, 1902, Steel Scrapbook 22:2, p. 46, Museum Collection, Crater Lake National Park. Another request for a short piece on the lake met with a similar response; Muir to Steel, December 15, 1906, SL, Box 2, Item 22.

40. Pinchot to Steel, February 18, 1902, SL, Box 2, Item 20A.

41. Thomas H. Tongue [Oregon Congressman] to Steel, April 18, 1902, Box 2 Item 21F.

42. Pinchot to Steel, May 15, 1902, SL, Box 2, Item 20D.

43. The Oregon Forestry Association was founded in 1896 as another way to defend the Cascade Reserve. Pinchot made it a point to visit Stehekin that summer after Steel failed to receive a patronage appointment as forest superintendent in Oregon. Steel, however, was more inclined toward forest recreation than was Pinchot; see Steel, “The Valley of the Stehekin”, The State2:1 (July 20, 1898) in Steel Scrapbook 10:2, Mazamas Library, Portland.

44. Wolfe in John of the Mountains, 379-380, gives Muir’s journal entry for May 29, 1899: “Met Judge George. Had a long talk on forest protection, found him lukewarm. Mr. Steel uncertain on the same subject. Told him forest protection was the right side and he had better get on record on that side as soon as possible. He promised to do what he could against sheep pasture in the Rainier Park and also in the Cascade Reservation”

45. No national parks have been established in Oregon since the Forest Service was created. The Forest Service administered Oregon Caves National Monument from its proclamation in 1909 until 1993, when it was transferred to the National Park Service by executive order. John Day Fossil Beds National Monument is a former state park.

46. The sugar pines discussed in Ise, pp. 406-407, as is the Hetch Hetchy controversy on pp. 85-96.

47. Quoted September 7, 1930, History Files, Crater Lake National Park.

William Gladstone Steel – Mazamas Founder:

A Chronology compiled by Stephen R. Mark, Historian, Crater Lake National Park

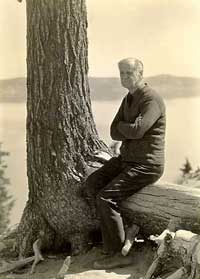

Portrait of Mr. Steel seated on base of only surviving tree around which ropes were snagged to launch first boats. (National Park Service Historic Photograph Collection.)

1854 Born on September 7 in Stafford, Ohio. His father William was a Scottish immigrant who came to Virginia in 1817 at age 8. His mother was a Virginia native, the former Elizabeth Lowry.

1868 Steel family left Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, for southeastern Kansas on March 25. They settled on a farm near Oswego in Labette County.

1870 Read about Crater Lake for the first time, supposedly in a newspaper containing his lunch.

1872 Family left Kansas for Portland, Oregon, where they joined two of Will’s brothers who had become successful financiers.

1873 Will completed high school in Portland and began a three-year apprenticeship as a pattern maker for Smith Brothers Iron Works. Started collecting newspaper clippings to place in scrapbooks.

1875 Is said to have acquired an interest in mountaineering.

1879 Father William Steel died January 5. Later that year Will became president of Portland’s Philomathean League, a society for oratory and debate. In October he established the Albany (Ore.) Herald in an attempt to carry Linn County for the Republican Party. The paper was sold the following summer.

1881 With his brother David, Will initiated publication of a promotional journal called The Resources of Oregon and Washington in November. Their main business associate was Chandler B. Watson, who had visited Crater Lake in 1873.

1885 Steel arrived at Crater Lake for the first time on August 15. Two days later he christened Wizard Island. On his return to Portland, Steel consulted with Judge John B. Waldo in Salem about a proposal to establish Crater Lake as a national park. Will’s professional status at this time was as superintendent of postal carriers in Portland, owing to his brother George being postmaster.

1886 At Steel’s urging, two national park bills were introduced in Congress during January. On February 1 President Cleveland reserved ten townships around the lake from settlement. Will directed the transport of equipment for a U.S. Geological Survey expedition to Crater Lake in July.

1887 On July 4 was the first person to successfully illuminate Mount Hood at night. Organized the Oregon Alpine Club in September.

1888 Met John Muir for the first time in August. During that month Steel planted the first fish in Crater Lake and made his only known journey to the Oregon Caves.

1889 Attempted to find investors for a railroad to run from Drain to the mouth of the Umpqua River. Assisted in the reorganization of the Oregon Alpine Club.

1890 Published his only book, The Mountains of Oregon, through his brother David. That summer Steel had the OAC co-sponsor the O’Neil expedition of the Olympic Mountains. At its conclusion, members express their gratitude to him at a dinner in Hoquiam, Washington.

1891 Formed a real estate partnership called Wilbur & Steel in Portland. For the next two decades Steel assisted with the development of North Portland, especially the area near what is presently University Park and Portsmouth.

1892 OAC declared bankruptcy after Steel had used $1000 of his own money for its operations.

1893 A four million acre Cascade Forest Reserve was established by executive order. The predecessor to several national forests and Crater Lake National Park, Steel and Waldo played the largest role in lobbying for its creation.

1894 Organized the Mazamas on the summit of Mount Hood on July 19. Some 193 people made the ascent, many from Steel’s cabin near Government Camp.

1895 Traveled to Washington DC to foil the first Congressional attempt at rescinding the Cascade Forest Reserve.

1896 Led a Mazama trip to Crater Lake in August. Steel also facilitated the investigations of several government scientists in conjunction with the gathering. Later in the month he brought the National Forestry Commission to the lake. Founded the Oregon Forestry Association as a result of his interest in Pacific Northwest forests.

1897 Failed to secure a patronage appointment as superintendent of the Cascade Forest Reserve. During the summer and fall worked as a forest reserve surveyor for the U.S. Geological Survey in the vicinity of Stehekin, Washington.

1900 Married Lydia Hatch in Portland on February 16.

1901 Steel’s fish planting of 13 years before was declared a success when trout were discovered in Crater Lake.

1902 After 17 years of painstaking effort, Steel was triumphant when Crater Lake National Park was established on May 22.

1903 Brought 27 people to Crater Lake from Medford on August 5. This was his first attempt to provide visitor services at the lake.

1906 Initiated publication of a pamphlet series called Steel Points. Resigned from Mazamas on August 30.

1907 Established the Crater Lake Company with E.D. Whitney in Portland on June 6. As the park’s first concessioner, he provided transportation for tourists, a tent camp at Annie Springs and boat tours on the lake.

1909 Opened Camp Crater at the rim on July 20. After choosing the site where the Mazamas gathered in 1896, Steel supplied the funds to begin construction of the Crater Lake Lodge.

1912 Secured federal funds for the construction of a road around Crater Lake. Sold his financial interest in the Crater Lake concession to his Portland real estate partner, A L. Parkhurst.

1913 Appointed as Crater Lake National Park’s second superintendent on June 7.

1914 Endorsed government ownership of the park’s concessions as a way of helping the faltering Parkhurst complete his development at the rim.

1915 Was on hand when the partly-completed Crater Lake Lodge opened on July 3. After a visit by William Jennings Bryan, Steel recommended that an elevator be constructed from near the lodge to the lakeshore.

1916 Resigned as superintendent on November 20 in order to accept the position of park magistrate. The job as magistrate was created after the State of Oregon ceded jurisdiction over Crater Lake to the Federal Government a year earlier.

1920 Took up residence in Eugene.

1921 Rejoined the Mazamas.

1924 Published a pamphlet titled “The Crater Lake Scandal” on January 1. It was written to protest the treatment of Parkhurst, who had been forced to give up the Crater Lake concession in 1920.

1925 His speech before a Eugene service club on Lincoln’s birthday was self-published, as was a volume of Steel Points Junior called “Crater Lake Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow”.

1927 Published his last pamphlet, a volume of Steel Points Junior.

1929 Relocated to Medford. Its newspaper reported Steel’s intent to assist with the growth of Oregon’s state park system once the parks had been incorporated into the State Highway Division.

1932 Initiated a campaign to build a road inside the caldera from Rim Village on May 22. Made his last visit to Crater Lake that summer, after which he suffered a long illness. Lydia Steel died in Medford on November 9.

1934 Died November 21. Buried in Medford’s Siskiyou Memorial Park wearing his NPS uniform.

Other pages in this section