Cultural Landscape Recommendations: Park Headquarters at Munson Valley, Crater Lake National Park, Oregon

SUMMER 1991

Date of Inventory: July 1990

Project Team: Cathy Gilbert, historical landscape architect and

Marsha Tolon, landscape architect.

Contents

Introduction

Identification

History

Army Road Crew Occupation, 1913-1918

NPS Government Camp, 1924-1941

Park Headquarters, 1941-Present

Analysis and Evaluation

Response to Natural Features

Spatial Organization

Land Use

Vegetation

Cluster Arrangement and Structures

Circulation

Small-Scale Elements

Statement of Significance

Criterion A:

Criterion B:

Criterion C:

Criterion D:

Recommendations

Maintenance and Management Concepts

Buildings and Structures

Circulation and Access

Vegetation

Site Details and Materials

Special Site Area

Administrative Complex

Administrative Complex Structures

Superintendent’s Residence

Notes

References

Appendix A: Castle Crest Wildflower Garden

Context

Physiographic

Cultural and Political

Historic Significance

Plant List of the Castle Crest Wildflower Garden

Notes

References

Introduction

This Cultural Landscape Catalog provides a preliminary analysis and evaluation of the historic landscape at Munson Valley in Crater Lake National Park. The purpose of the Catalog is to identify and evaluate historic landscape resources, and based on that evaluation, develop preliminary guidelines and recommendations for preservation, rehabilitation, maintenance, and interpretation of those resources. This document is a technical supplement and does not replace a standard cultural landscape report. Additional work will be required prior to implementation of specific recommendations and/or design concepts. Both the Catalog and future projects resulting from the Catalog’s programmatic information will receive review from appropriate local, state and federal entities.

This Cultural Landscape Catalog provides a preliminary analysis and evaluation of the historic landscape at Munson Valley in Crater Lake National Park. The purpose of the Catalog is to identify and evaluate historic landscape resources, and based on that evaluation, develop preliminary guidelines and recommendations for preservation, rehabilitation, maintenance, and interpretation of those resources. This document is a technical supplement and does not replace a standard cultural landscape report. Additional work will be required prior to implementation of specific recommendations and/or design concepts. Both the Catalog and future projects resulting from the Catalog’s programmatic information will receive review from appropriate local, state and federal entities.

Project boundaries are based primarily on the Munson Valley Historic District boundaries, yet are drawn to reflect the physiographic characteristics defining the district. When the field inventory occurred, the employee cabins at Sleepy Hollow had been demolished and new quarters were being constructed at the site. Due to the loss of historic integrity the area was considered non-contributing to the extant historic district and was not included in this project. However, the new development at Sleepy Hollow contains design elements and characteristics based on historic precedent; future preservation work for Munson Valley may include the area as part of the project boundary. The Castle Crest Wildflower Trail, as a designed landscape, is significant for its association with the Park Headquarters area and National Park Service interpretive programs of the mid-1920s to the mid-1930s. Located adjacent to the study area, access to the trail begins at the east boundary of the historic district and project boundary. Preliminary documentation of the trail as a cultural landscape is included in the appendix of this report.

This document was developed in the Pacific Northwest Regional Office by the Cultural Resources Division. Previous documents prepared for the park addressing historic resources at Munson Valley include: Historic Resource Study, Crater Lake National Park, 1984; Munson Valley’s Designed Landscape, 1990; and The Rustic Landscape of Rim Village, 1927-1941. Crater Lake National Park, 1990.

Identification

| NAMES | ACCESS |

| COMMON: Park Headquarters | X YES–Unrestricted |

| HISTORIC: Government Camp | X YES–Restricted: Residential/Maintenance |

| _ NO ACCESS | |

| LANDSCAPE TYPE | OWNERSHIP |

| HISTORIC: Administrative/Residential/Maintenance Area | X Public |

| CURRENT: Administrative/Residential/Maintenance Area | _ Private |

| _ Both | |

| LOCATION | NATIONAL REGISTER STATUS |

| USGS Quadrangle: Crater Lake National Park and Vicinity, Oregon T30S R5E, Klamath County |

X Listed: Munson Valley Historic District, 1988 |

CONTEXTUAL BOUNDARIES

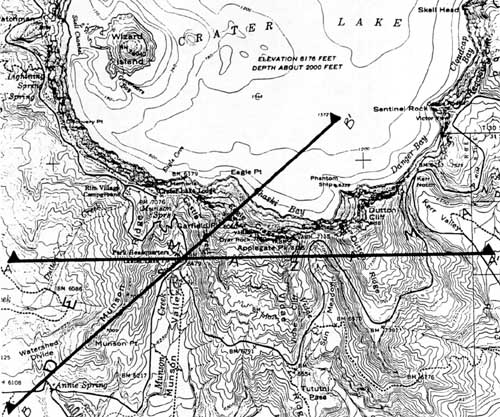

PHYSIOGRAPHIC

CULTURAL

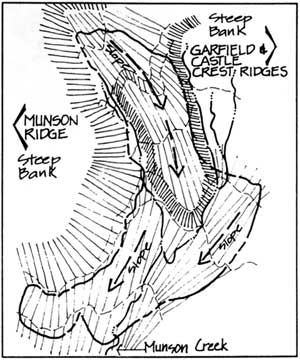

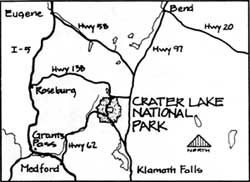

Park headquarters is located in Munson Valley, one of three prominent glacial valleys on Mount Mazama’s south flank. The valley is north-south trending and holds Munson Creek, a spring-fed tributary of Annie Creek that eventually reaches the Klamath Basin, southeast of the park.

Park headquarters is located three miles south of Rim Village. Munson road connecting Highway 62 and Rim Village creates the east boundary of the site.

POLITICAL

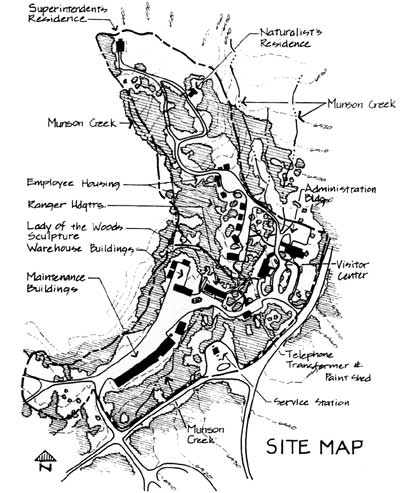

The site contains administrative offices for Crater Lake National Park and Oregon Caves National Monument, utility buildings, and employee housing. The property is owned and managed by the National Park Service and is registered as the Munson Valley Historic District.

SITE BOUNDARIES

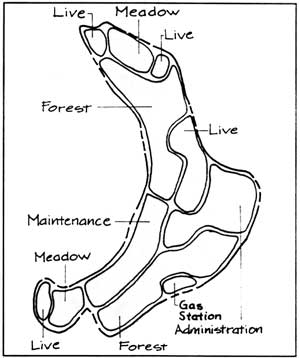

A mature forest creates an edge along Rim Drive to the southeast and west sides of the maintenance area. Clearings in the canopy cover mark the Administration Building and Visitor Center entrance on the east edge of the site, and the Superintendent’s and Naturalist’s residences in the northern portion of the site.

A mature forest creates an edge along Rim Drive to the southeast and west sides of the maintenance area. Clearings in the canopy cover mark the Administration Building and Visitor Center entrance on the east edge of the site, and the Superintendent’s and Naturalist’s residences in the northern portion of the site.

VEGETATION

TOPOGRAPHIC

The valley walls are distinct features to the west and east of the site, creating an enclosed crescent shaped space. Munson Creek creates an edge on the northwest and northeast.

CIRCULATION

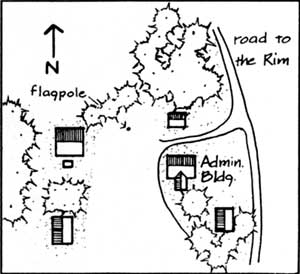

Munson road connecting Highway 62 and Rim Village creates a strong site boundary on the east. Within the site, more discrete areas are created by an intersection of roads leading south to the maintenance area, and to the Steel Circle housing area.

STRUCTURES

Maintenance area, looking north, 1990

Maintenance area, looking north, 1990

History

ARMY ROAD CREW OCCUPATION, 1913-1918

| U.S. Army Corps of Engineers headquarters, looking south, 1910’s

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers headquarters area c. 1917 |

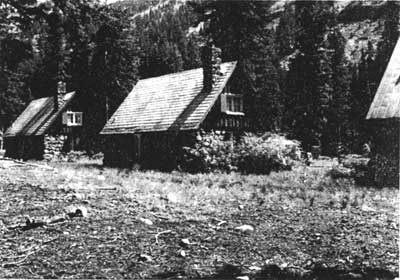

A 1911 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers survey convinced Congress to fund construction of a road around Crater Lake. In 1913, money was appropriated for the project, and road opening scheduled for late 1918. A site central to the park’s proposed road system was selected at the upper end of Munson Valley by the Corps as a seasonal headquarters site. The headquarters site was located three miles from the rim in an area relatively protected by the surrounding valley walls where water and wood for building materials were readily available.

In conjunction with the first work season, the army built six log structures with steeply-pitched roofs including a headquarters building, storage barn, blacksmith shop, aid cabin, and cook shack that housed a kitchen/dining room downstairs and a dormitory upstairs. The structures were clustered on both sides of the main road to the rim, bisecting the site, and creating a general north-south orientation to the complex. There were no other “formal” roads through the site (or defined parking), and other than this main road, circulation was generally random and unstructured. Because of this random pattern of circulation, vegetation around the complex was virtually eliminated. With the exception of a flagpole erected near the headquarters building, and a stone sculpture, the landscape was primarily functional with little ornament. Open areas functioned as service and staging areas for Army crews. Built only for seasonal use during the short construction season, the complex was abandoned by the army when the road was complete in 1918.

Few remnants from the Army road crew occupation in Munson Valley exist today. Aside from several road segments that have been well disguised over the years and a general concentration of administrative uses, the Lady of the Woods sculpture is perhaps the only physical feature remaining from the Army’s presence in the area. The stone sculpture was carved in 1917 by Earl Russell Bush, a medical doctor who was attached to the Munson Valley road project and wanted to express his “deep love for the virgin wilderness.” It is located west of the administrative compound.

A similar intent was to guide systematic efforts of the National Park Service to implement the landscape design at Munson Valley in the 1930’s.

A similar intent was to guide systematic efforts of the National Park Service to implement the landscape design at Munson Valley in the 1930’s.

NPS GOVERNMENT CAMP, 1924-1941

Increased visitation to Crater Lake National Park and the use of the site as seasonal quarters for park staff led park officials to make Munson Valley a summer headquarters for park operations in 1924. Within a year of moving to the site from Annie Springs, an addition was made to the former engineer’s office, and the building was converted to serve as the park administration building. Though the site provided much needed space, it was soon apparent that the complex was inadequate for the park’s needs. In 1925, as part of a park-wide planning program under the direction of Thomas Vint, work was underway on a general master plan for redevelopment of the site. The planned development took “…advantage of topography and forest screening to place out of sight almost every building that is not of direct concern to the visitor.”

| NPS Government Camp, c.1930

NPS Government Camp, looking north, 1934

Administration building and plaza, looking north, c.1935 |

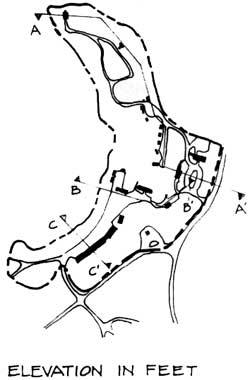

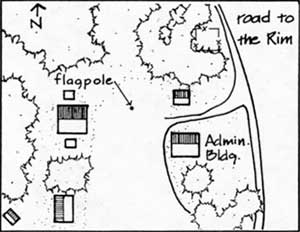

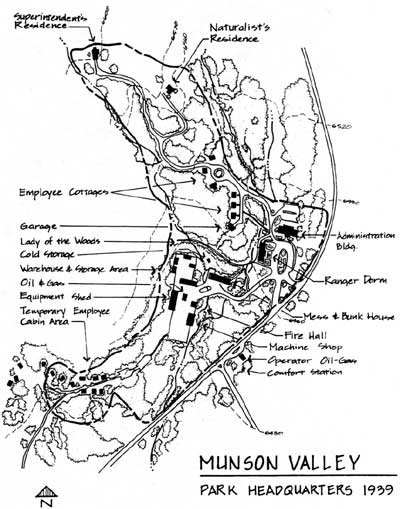

Thus, at Government Camp, the only building that will be in sight when this program is finished will be the Administration Building, the Museum [Ranger Dormitory] and Service Station [removed in favor of the present one]…”(2). Implementation of the master plan for Munson Valley began in 1927. The major components of the plan included the development of a new administrative complex, utility and maintenance area, residential areas for staff and seasonal employees, a formalized circulation system, and a revegetation program for the site as a whole. Initial construction focused on basic services and operations. Between 1927 and 1930, four small cottages, a mess hall, comfort station, meat house, warehouse and two utility buildings were constructed. The road from Munson Valley to the rim was relocated to its present location early in the development of the site (ca 1927), but the majority of other roads, pedestrian walks and trails, and bridle trails remained informal in character. Structures were rustic in character. Over scaled elements such as locally quarried stone and timber were used to blend, in scale and color, with the surrounding trees and rough terrain. The 1931 master plan outlined the need for as many as 21 additional buildings in addition to extensive road improvements, utilities, and plantings, but it wasn’t until the 1932-1933 season that intensive development in the district was undertaken.

With the realignment of the road to the rim, and the new design for the plaza, there was need for general revision of the road system throughout the district. The main entrance road was moved so that entry to the site was from the east. The old road was obliterated and planted. Secondary roads provided access throughout the site, linking residential areas, service areas, and the utility area. These roads were surfaced with gravel and then oiled to reduce dust and provide an improved driving surface. The trail to the Lady of the Woods was also surfaced with gravel.

In the 1932-33 construction season, several major buildings and site structures were built. Two large residences–a superintendent’s house and a naturalist’s house–were completed, along with four utility buildings, a comfort station, additional employee residences and a dormitory for the rangers.

In 1934 the old log administration building was removed and construction of a new rustic stone administrative structure was underway. Stone curbing was set along the roads through the center of the site creating a circular drive and a more defined and structured circulation system. The plaza in front of the new administration building was designed to accommodate 50 cars, and had a large elliptical planting island in the center. This area was planted based on a design by landscape architect Francis Lange, and included 13 varieties of plants. Additional landscape work was done around the cottages on the hill above the plaza. Structural additions to the Mess Hall and Warehouse as well as the construction of a garage/woodshed and three frame storage sheds were all completed in this construction season.

Major landscape work was undertaken over the 1933- 34 construction seasons. Over a thousand trees and several thousand shrubs were transplanted to the area as part of the “naturalization” program for the site begun by landscape architect Merel Sager. Civilian Conservation crews (C.C.C.) planted shrubs at the newly constructed residences that had proven successful at Rim Village, including spirea, mountain ash, willow and twinberry (purple flower honeysuckle). In 1936, landscape work at the new Administration Building went beyond previous efforts using sedges and grasses for the open areas, several shrub species and tree groupings of mountain hemlock, lodgepole pine, and subalpine fir. Large quantities of top soil and peat were brought in from the south end of the valley to supplement, and in some cases, to replace the pumice soil prior to planting. Small-scale features including flagstone walks, rustic signs, stone bridges, planting beds and drinking fountains were incorporated into the landscape for both functional and design objectives. Additional road improvements were made and a parking area was added in back of the Administration Building (1936). A new parking facility was added in front of the Mess Hall and below the Machine Shop in 1938. Numerous “bitumuls” walks were installed around the Rangers’ Dormitory and the Administration Building.

Until 1938 park headquarters was known as “Government Camp.” In order to avoid confusion with Government Camp on Mount Hood, some 180 miles north of the park, the name was changed to Park Headquarters by Superintendent Ernest P. Leavitt. Munson was the name of an early visitor who died on a ridgeline two miles southwest of the headquarters site in 1872.

Although some planting and landscape work took place at the residential complex in 1940, by 1939 the designed landscape at Munson Valley was largely in place. In terms of a construction sequence the architectural structures generally preceded the installation of plant materials and other landscape features at the site. In terms of stylistic objectives, landscape treatments were a critical component of the site, and were designed to integrate man-made structures and circulation systems into the natural surroundings using weathered boulders, masonry, and rustic wood signs to accentuate design elements and evoke a rustic appearance.

PARK HEADQUARTERS 1941-PRESENT

Vint, Sager, Lange and others were against using Munson Valley as a year-round headquarters area, recommending instead that a suitable site at lower elevation be developed. However, after WW II, year- round operations at Munson Valley began, although winter occupancy was not officially approval until 1982. This was a major shift in the function of the area and had tremendous impact on the designed historic landscape. Landscape features including curbing, planting beds, porches, and narrow roads with curves were all seen as obstacles to the snow plow. Structures with steeply pitched roofs tended to dump snow close to the building preventing access and requiring the addition of tunnels on a seasonal basis.

|

Lower group of employee residences on the spur road, rear view, 1990 |

In 1954 all of the planters, lawns, and walks around the employee cottages were removed to accommodate the snow plow. The traffic island near the upper group of cottages was also removed to allow turning radius for the snow plow. Roads throughout the district were widened. The utility building, which had enclosed the maintenance area was removed in order to allow snow plow access through the entire area. This building was later replaced by a machine shop in 1966.

|

View south along spur road showing typical post WW II snow tunnel addition and widened road bed, 1990 |

Additional changes included the obliteration of the old access road to the site, construction of a new gas station across the road from the existing one, which was later removed, and realignment of the intersection with Munson Road. The now abandoned second gas station will be removed in 1992. The Firehall was removed in 1969 and the Oil House was removed in 1990. In 1986, the Ranger Dorm and the Administration Building were rehabilitated. A permanent snow tunnel was added to the west side of the Administration Building replacing the south entrance tunnel built in 1958. A snow tunnel was also added to the east side of the Ranger Dorm. Despite the loss of plant materials and landscape detail in the administrative complex due to the adaptation of Munson Valley for winter use, the infrastructure of the original designed landscape is still evident. The site as a whole remains a good example of the Rustic style.

ANALYSIS AND EVALUATION

RESPONSE TO NATURAL FEATURES

View of Munson Valley from Garfield Peak looking southwest. Munson Point is located in the background right center.

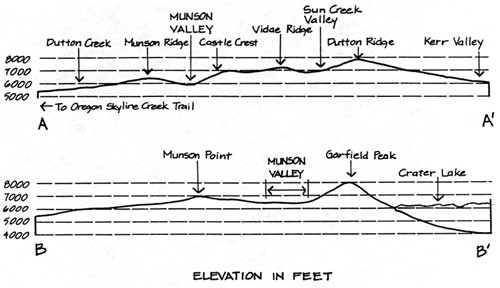

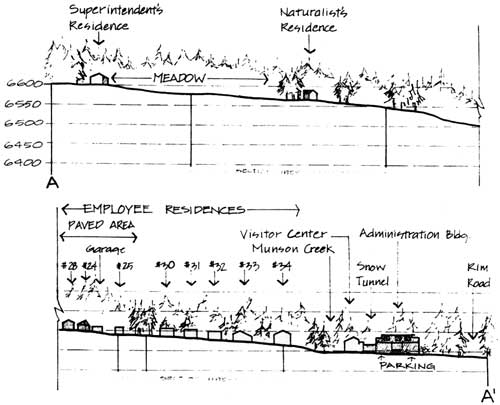

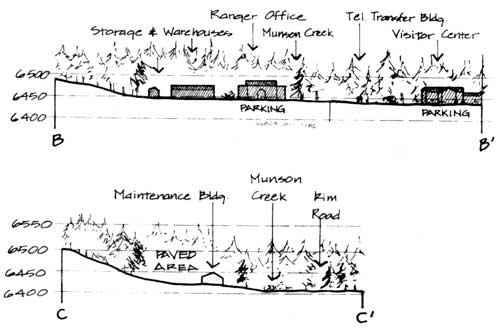

The natural landform and physiographic features of Munson Valley had a strong influence on the spatial organization and development of the Park Headquarters site. Most of the glaciated valley displays hummocky moraines intermixed with pumice, with the proportion of pumice gradually diminishing in the upper part of the valley. Linear sloped terraces of the valley provided natural siting opportunities for structures and roads and required only minimal grading. A steep north-south valley wall creates a west boundary for the site. Munson Creek, a spring-fed tributary of Annie Creek traverses and dissects the valley site into three distinct areas or subdistricts, physically stepping down in elevation from north to south. The Munson drainage is part of the Klamath Basin, an area south of the caldera and east of the Cascade Divide (Munson Ridge).

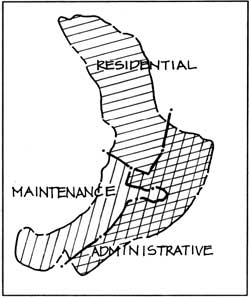

SPATIAL ORGANIZATION

Munson Creek divides this glaciated valley into three spatial areas which reflect a specific hierarchy of land use: residential, administrative and maintenance. Thomas Vint’s 1925 master plan sited three contiguous complexes within these areas with the administrative complex as the structural and symbolic center. Forest canopies and meadows separate and distinguish activity areas creating visual buffers between the residential areas at the highest elevations on the north end of the site, and the maintenance area on the south end. As stated in the 1928 plan, the administrative complex had potential for visitor contact and remains the most prominent and commanding area of the park headquarters complex.

Munson Creek divides this glaciated valley into three spatial areas which reflect a specific hierarchy of land use: residential, administrative and maintenance. Thomas Vint’s 1925 master plan sited three contiguous complexes within these areas with the administrative complex as the structural and symbolic center. Forest canopies and meadows separate and distinguish activity areas creating visual buffers between the residential areas at the highest elevations on the north end of the site, and the maintenance area on the south end. As stated in the 1928 plan, the administrative complex had potential for visitor contact and remains the most prominent and commanding area of the park headquarters complex.

|

Munson Creek in the residential area. |

|

LAND USE

|

NPS Government Camp, 1939 |

Historically, the headquarters complex at Munson Valley was organized as a hierarchy of spaces according to land use function and activity. With the exception of seasonal employee housing at Sleepy Hollow to the southwest, residences were grouped in the north end of the site. The Superintendent’s residence and the Naturalist residence, both display site design principles common to the period used in “estate planning” (residential planning). Sited at slope apex the aim was to “suggest openness and freedom, a naturalistic treatment, at least an informal treatment…[where] the lawn is treated as an extension towards the observer of a distant outside view,…making the estate seem larger than it is by merging its boundaries in those of the surrounding country and repeating within the estate planning found in the adjoining scenery.” South of these structures and separated from them by open areas of meadow and pumice fields, the administrative buildings were located in the center of the site.

|

NPS Government Camp, 1939 |

This broad level area functioned as the heart of the site, a focal point of activity. Located southwest of the administrative area in the lowest portion of the site are the maintenance and utility areas. During the historic period the maintenance area was closed on three sides, efficient for use during the summer season. In contrast the present layout is two sided, designed to accommodate vehicle parking and winter snow plows. The service oriented function of these structures is reflected by their site location in an outer area of the development away from visitor contact.

This original land use pattern generally continues in the same configuration today. Housing for permanent employees is located at Steel Circle south of the maintenance area, while seasonal employee housing remains at Munson Valley. Although there have been several physical changes to the site over the years (roads widened and visitor and administration services expanded), the primary historic land use patterns have remained intact.

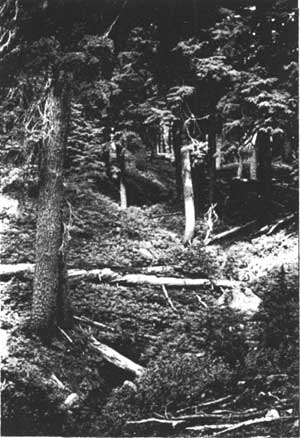

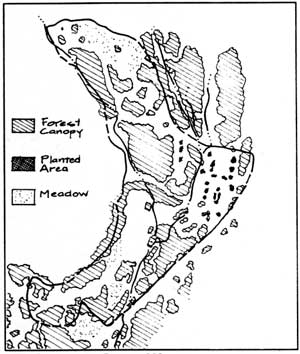

VEGETATION

|

NPS Government Camp, 1939 |

Mountain hemlock forest with open park-like meadows and sparse underbrush characterizes the vegetation cover of Munson Valley. These plants along with the presence of white bark pine, Shasta red fir, and noble fir are typical of the Hudsonian Life zone. Wood rush is the dominant understory; Scouler’s willow and subalpine fir are found along the creek and in low wet areas where montane meadow conditions exist.

The native plant community provided a palette for the landscape “naturalization” program of park headquarters. “Native materials were used because they were most suited to survive, not because they necessarily imitated the surrounding forest.” In terms of design and composition, the planting concepts and treatments used at Rim Village were also employed at Munson Valley. Plantings were used to establish vegetation where none existed, or in disturbed areas, to fill-out planting beds for design or functional purposes.

|

Subalpine fir |

The placement of trees and shrubs into groups was considered naturalistic not random. Plants such as Mountain hemlock and Subalpine fir were used to provide variation of texture and form, and because they did well at high elevations. Other shrubs such as honeysuckle, spirea, Scouler’s willow, and mountain ash were used to cast a sweeping appearance of boughs forming an unbroken reach of green. Near the Ranger Dormitory these materials were combined to create irregular plantings within a lawn of native grasses and sedges. Guided by landscape design principles of the period the planting design at Munson Valley included an emphasis on the placement of trees to promote their use as framing devices and as features which augment shade and shadow.

|

Sticky Currant |

With the exception of minor changes, naturalistic planting design principles have provided the foundation for the relatively unchanged appearance of park headquarters. To accommodate efficient snow removal some plantings (among other landscape features) were removed in 1944. In 1954, planted islands in front of the middle row of employee cottages, and between the warehouse and messhall were removed. In 1958, the south entrance to the administrative complex was obliterated and planted. Landscape architects wanted to blur the distinction between “formal design” and the natural vegetation of the site. The survival of many remnant plant materials such as alpine perennials in the ellipse at the administrative complex, hint at the original planting scheme.

Plant Materials Transplanted 1933-37

| Trees | |

| Abies lasiocarpa | subalpine fir |

| Pinus contorta | lodgepole pine |

| Tsuga mertensiana | mountain hemlock |

| Shrubs | |

| Acer glabrum | Rocky Mountain maple |

| Anaphalis margaritacea | pearly everlasting |

| Aquilegia spp. | columbine |

| Castilleja spp. | Indian paintbrush |

| Dicentra spp. | bleeding heart |

| Erigeron spp. | fleabane |

| Gilia spp. | gilia |

| Helleborus spp. | hellebore |

| Holodiscus discolor | oceanspray |

| Juncus | rushes |

| Kalmia microphylla | western laurel |

| Lonicera conjugialis | purple-flower honeysuckle (twinberry) |

| Phlox spp. | phlox |

| Polemonium caeruleum | Jacobs ladder |

| Ribes erythrocarpum | Crater Lake current |

| Salix scouleriana | Scouler’s willow |

| Sambucus racemosa | red elderberry |

| Sedge | Sedge spp. |

| Sorbus sitchensis | Sitka mountain ash |

| Spiraea densiflora | subalpine spirea |

| Vaccinum spp. | huckleberry |

| Arctostaphylos nevadensis | pine-mat manzanita |

Existing Vegetation

| Trees | |

| Abies magnifica shastensis | Shasta red fir |

| Abies lasiocarpa | subalpine fir |

| Pinus albicaulis | whitebark pine |

| Pinus contorta douglasi | lodgepole pine |

| Sorbus sitchensis | Sitka mountain ash |

| Tsuga mertensiana | mountain hemlock |

| Shrubs | |

| Acer glabrum torr. | Torrey maple (Rocky Mountain maple) |

| Lonicera conjugialis | purple flowered honeysuckle (twinberry) |

| Luzula glabrata | smooth woodrush |

| Ribes viscosissimum | sticky currant |

| Salix scouleriana | Scouler’s willow |

| Salix sitchensis | Sitka willow |

| Spiraea densiflora | subalpine spirea |