Volume 14, September 1948

All material courtesy of the National Park Service. These publications can also be found at http://npshistory.com/

Nature Notes is produced by the National Park Service. © 1948

Brief Eruption

It was Sunday afternoon in August, and Sinnott Memorial was full almost to the parapet. The lecturer had finished his discussion of the cycles of eruption and quiet. Trying to stir the interest of his audience, he started speculation on the possibilities of renewed volcanic activity. To ease any fears which they might have about the mountain exploding under their feet, he mentioned that any major eruption would undoubtedly be preceded by loud rumblings and at least some vibration of the earth. At this moment a tremendous roar struck the intent faces of his listeners. It was a full five seconds before the taut, fearful expectancy was broken by a nervous laugh. One by one visitors resumed breathing as they caught sight of the first jet planes to buzz Crater Lake disappearing over Llao Rock.

Unusual Plant Fare

Denis Illige, Ranger-Naturalist

A trip afield on a day off from the normal duties of a ranger-naturalist is often full of surprises. While on a trip to Copeland Creek with Ranger-Naturalist D. S. Farner and Ranger Glenn Brady, “to see what we could see”, a brief stop was made in a wet meadow above the headwaters of Copeland Creek. The purpose of this particular stop being to investigate the frog population, each of us went a different direction, cautiously moving along, carefully investigating the marshy areas for frogs. While so occupied, a small moth was seen entangled in the swamp grass, struggling vigorously. This being an unnatural place for a moth, closer scrutiny disclosed that it was trapped by that plant nemesis of inset life, a carnivorous plant, this one known as Sundew.

Plant life in general is characterized by a relatively mild attitude toward most animal life, particularly in respect to capturing and devouring animals. However, there are a few exceptions, Sundew or Drosera being one found in Oregon. The moth that led to the discovery of Sundew in Crater Lake National Park was entangled by the sticky “fingers” of a Sundew. These “fingers” are small hair-like projections from the leaf-blade of this plant. From the ends of these hairs is exuded a clear, neutral, sticky fluid. When a luckless insect brushes against the sticky hairs, he is indeed fortunate if he is large, or strong, enough not to be caught. Usually in the struggles of a hapless insect, he only succeeds in making matters worse for himself by agitated struggling, more contacts being made at each spasm of movement.

When the insect is solidly within the grasp of the Sundew, the leaf folds in toward its center, the sticky fluid becoming more acid, changing to a proteinaceous ferment capable of digesting the insect tissues. The digested tissues are then absorbed by the Sundew for some of its nutritional needs.

This is the first authentic record of Sundew in Crater Lake National Park. It had been reported by F. Lyle Wynd, but the specimens were note located nor the locality of the collection recorded.

E. I. Applegate, in all of his extensive collecting, did not discover it either. The area from which the present collection was made was from a patch of about 200 square feet in size, on a boggy side hill with a western exposure. The area is exposed to brilliant sunlight for most of the day. The elevation was determined from a map as about 5600 feet above sea level.

The origins of both the common name, Sundew, and the scientific name, Drosera rotundifolia, are of interest because of their aptness. The plant habitually grows in open, well-lighted places, and the clear, sticky fluid exuded at the end of the leaf hairs sparkles in the bright sunlight as do drops of dew on other plants. The scientific nameDrosera is of Greek origin, meaning dewy, while rotundifolia refers to the rounded shape of the leaves.

Ornithological Notes of Interest

By Staff

Farallon Cormorant:

Thus far this summer (August 10, 1948) there has been only a single Cormorant reported from Crater Lake. On August 7, 1948, one was seen in flight near Cloudcap, apparently from the surface of the lake. Mr. Paul Herron, who operates the launch in a daily trip around the lake, had not seen Cormorants previously this year. No Cormorants were seen on Crater Lake in 1946. According to Mr. Herron and Dr. Ruth Hopson, there were none during the summer of 1947. This is in striking contrast to the summers of 1939, 1940, and 1941 when daily a group of ten or more of these fish eaters could be seen on the Phantom Ship. It is of interest to note that in 1939, 1940 and 1941 fish were abundant in Crater Lake, whereas in 1946, 1947 and 1947 fish were relatively scarce and fishing was poor.

Long-legged Birds:

Rare in the park, a white egret was seen stalking a quiet pool in Annie Creek near the South Entrance on August 31, 1947, while a blue heron was observed winging its way down the middle fork of Annie Creek the following day.

Western Crow:

Although the Western Crow quite likely appears from time to time within the limits of the park, there seems to be no actual record of such up to this time. On June 24, 1948, one was seen in flight over Munson meadows, and on July 2, 1948 two more were seen, one along Annie Creek Canyon about two miles below Annie Spring and another along the highway between Annie Spring and Park Headquarters. In view of the fact that crows and ravens rarely occur commonly together in an area, and that ravens are relatively common, the sparsity of crows in the park is understandable.

Sierra Creeper:

On November 30, 1947, four feet of snow covered the ground at Park Headquarters. It was cupped to the ground around the bases of trees near the Administration Building. From the depths of one of these issued a familiar, though unexpected, note of high pitch. And then, seemingly quite at home in a red fir in spite of the cold, appeared a little Sierra creeper. These birds reside in fir forests in the park in summer and are known to winter around Fort Klamath but this appears to be the only winter record inside the park.

Rock Wren:

Usually a common denizen of the talus slopes, disintegrating outcrops, and other similar areas where its energetic, distinctive trills blend into a unique pattern of sound with the acute whistle of the marmot and plaintive cry of the coney, the Rock Wren has been conspicuously absent during the summer of 1948. Not a single record has been reported from the entire park. In no previous year in which records have been kept has there been this complete absence of the species.

Townsend’s Solitaire:

Although this inauspicious songster has little in its doleful, ashy plumage to suggest its true familial affiliation, an instant of its heterogeneously rich song immediately identifies it with the other thrushes. The sight of this inconspicuous thrush with its white outer tail feathers and buffy wing spots, as it flutters gracefully to the ground to obtain an insect and returns to perch is not frequent in Crater Lake National Park. More frequently the male is to be seen, and heard, from the apex of a bare stub, often a hundred feet from the ground. It is almost paradoxical that the occupant of so lofty a song perch should nest on the ground; but such is almost invariably the case. On July 1, 1948, a nest with four downy young was found in an unprotected place on the ground on the west bank of Sand Creek. Only a single parent was observed to be caring for the young. This appears to be the first recorded observation of the nesting of this species in the park.

Short-tailed Chickadee:

Chickadees are the abundant acrobatic light percussioneers of the evergreen symphony. In autumn particularly, their unmusical vocalizations are warmly welcome to the ears of the ornithologists for they frequently constitute the nucleus of conglomerate flocks of Juncos, Chickadees, Chipping Sparrows, Warblers, and other species which wander through the coniferous forests during this season. Despite the ubiquity and abundance of these clamorous tits, our knowledge of the nesting habits of this species in Crater Lake National Park is amazingly sparse. During the course of the summer of 1948 three nests have been observed. On July 7 a pair was noted to be attending a nest in the utility building in the lower residential area at Park Headquarters. By July 12 food was being carried to the nest by both parents, indicating that young were being fed rather than food being carried to an incubating adult. On July 26 a nest was discovered in a dead Mountain Hemlock near the stone quarry; both parents were carrying food. On July 22 a nest was found in a dead Lodgepole Pine at the Junction of the Red Cone Motorway with the North Entrance Highway. These observations, and those of previous years, would indicate that nesting by this species in Crater Lake National Park must being in mid-June.

Slender-billed Nuthatch:

The insect and larva eating habits of this species and its more abundant and boisterous smaller relative, the Red-breasted Nuthatch, are of profound significance in the ecology of our coniferous forests. Together with certain of the Woodpeckers, the Chickadees, and the Creepers, the Nuthatches persistently depredate the populations of insects which frequent the barks of trees. Together with certain parasitic wasps and fungi these birds constitute the only natural control of many species of destructive insects. Prior to 1948 the Slender-billed Nuthatch had been regarded as a rare species of the higher altitudes whose breeding status was unknown. On July 12, 1948 a pair was found carrying food to a nest near the junction of the Crater Peak Motorway and the Rim Drive. Unlike the smaller Red-breasted Nuthatch which is sometimes noisy in the vicinity of the nest, these birds were completely silent.

Washington Lilies

By Dr. G. C. Ruhle, Ranger-Naturalist

Queen of American lilies is the real Washington Lily (Lilium washingtonianum), which grows in comparatively dry stands of brush in the arid Transition Zone from the Columbia River southward through the Sierras. Growing three to six feet tall, it bears clusters of a half-dozen or dozen very fragrant flowers that are white upon opening but turn first to pink, then to rose with age.

On the sunny manzanita-covered slopes of Copeland Ridge west of the lake at an elevation of 5500 feet, these lilies presented a superb display this year. Though frequently peering high above the red-boughed manzanita, some lower plants could be discovered by their sweet scent before they were detected by the eye.

The Retreat of Mount Mazama Glaciers

By William Kinsley

Glaciers once covered most of Mount Mazama and the country around its base. Howel Williams points out that during the stage of maximum glaciation, ice covered all but the highest pinnacles of the cascade divide.

The tremendous glaciers on the slopes of Mount Mazama have left scars in the form of U-shaped valleys. On the southern side of Crater Lake one can see Kerr, Sun, and Munson Valleys; all have the characteristic U-shape caused by moving rivers of ice. Here is mute testimony that large glaciers moved down the slopes of Mount Mazama, carving and gouging material from the sides of the valley. That material was ground into rounded boulders and fine sand; when the glaciers melted, the ground-up material was dropped in place forming glacial till.

Today the climate has changed to a point where only in the higher altitudes do the mountain peaks produce their rivers of moving ice. The geographers tell us that the average temperature of the world has been increasing is not known. Exactly what brings about this increase is not known. A decrease in temperature did occur over one million years ago that gave much of the land surface of our earth a coating of ice in the form of glaciers. This is called the Pleistocene Epoch or “Ice Age”. In many recently glaciated areas of the world geologists have found evidence that there were four periods during the Ice Age when the glaciers dominated these areas, and three periods between when the glaciers were all but extinct. The cause of these cycles of fluctuation must have been caused by widespread temperature variations on the earth. They may have been due to a variation in the heat intensity from the sun, or perhaps a change of the axis inclination of our earth. Either of these changes could have been enough to produce far reaching temperature effects on the surface of the earth.

Wallace Atwood Jr. studied the layers of glacial till that are interbedded with Mount Mazama lavas. He found many more deposits of glacial till than could be accounted for by these climatic cycles. Some other major cause must be sought for the retreats which dropped these additional layers.

Throughout much of the Ice Age, Mount Mazama was building itself. Tremendous eruptions of molten material were ejected from the top or sides of Mount Mazama and flowed down the slopes, cooling in the sharp, cool air. Other times great cinder showers with pumice or volcanic ash fell back on the slopes, adding their material in the building process. There must have been times when great ice flows rested on the slopes when these molten lavas or cinder showers came forth, and the picture of explosive steam clouds and rushing waters issuing from the glaciers is one of appalling clearness. The melted waters rushed down the canyons below the glaciers, carrying with them large trees and boulders, dropping their load only when the momentum of the flood died away. Quite often the glaciers were completely melted away when volcanic activity persisted long enough. Surely then, there were times when the glaciers disappeared due to volcanic activity of Mount Mazama and not due to any climatic change in the region.

Thus the retreat of Mount Mazama glaciers was governed by both climatic and volcanic conditions. Material dropped from retreating glaciers gives, as yet, no hint as to which influence caused the retreat. If the geologist can ascertain the rate at which these glaciers melted, he may have the fundamental answer to this problem. Volcanic action upon the glaciers will produce fast retreats, while climatic temperature increase will give rise to slow retreats. Somewhere the answers lie in the rocks around Crater Lake.

Ways of Mazama Wildflowers

By Edwin Braun, Ranger-Naturalist

During the long winter, the slopes of old Mount Mazama are covered by a white blanket of snow. Except for the trees, evidence of life is absent; yet beneath the snow lie dormant the seeds, the roots and the runners of a host of plants, quietly resting.

Gradually the days lengthen, the snows cease and summer comes. The woods and meadows stir and begin to rouse from their dormancy. By June melting snow fills the creeks and gullies to the brim. At lower elevations the bare, brown ground begins to appear, at first only as small spots, but rapidly enlarging and merging one with another. Hardly has the snow left the ground, when small shoots, some red, some brown, some green, push their way through the soil. A few are impatient and grown through the thinning snow, spreading, their pale green leaves about it. Rapidly, leaves are produced, carpeting the bare ground in brilliant greens. Shrubs, whose bare but living branches have been buried under the snow, are set free and they, too, burst into green. These stages can be readily seen on any meadow during early summer. The white patches of snow are bordered by bare, brown, sterile-appearing soil, which in turn blends into brilliant green. Suddenly, in a matter of days, the green of woodland and meadow is flecked with colors, purples, pure white, bright yellow, blues, brilliant reds.

This is the life of the wild flowers in the park. The summer season is short, and except along streams, the porous pumice soil is dry and dusty well before the first snows fall in the middle of September. Therefore, in order to survive and to propagate their kind, everything must be secondary, to the business of producing flowers, of having them pollinated, and of forming seed in the shortest possible time. There is no time to dally in the sun growing many leaves and tall stems. The typical plant grows close to the ground, and even before the first leaves are mature flower buds appear. In years of short growing season this early production of flowers may mean the difference between survival and extinction. Many plants continue to bloom so long as there is enough moisture to support them, the flower stalk continuing to grow, producing new blossoms at the tip and maturing the seeds of the older ones below. This device enables them to take advantage of an especially long growing season and thus produce a maximum number of seeds.As the season advances, the retreating snows are followed up the slopes of the mountains by wide expanses of flowering plants. This riot of color lasts but a short while, then is gone. The porous soil dries, the green turns red and brown, seeds are shed. The year’s growing season is over; soon the snows will come and again all will be white and silent.

This is the life of the wild flowers in the park. The summer season is short, and except along streams, the porous pumice soil is dry and dusty well before the first snows fall in the middle of September. Therefore, in order to survive and to propagate their kind, everything must be secondary, to the business of producing flowers, of having them pollinated, and of forming seed in the shortest possible time. There is no time to dally in the sun growing many leaves and tall stems. The typical plant grows close to the ground, and even before the first leaves are mature flower buds appear. In years of short growing season this early production of flowers may mean the difference between survival and extinction. Many plants continue to bloom so long as there is enough moisture to support them, the flower stalk continuing to grow, producing new blossoms at the tip and maturing the seeds of the older ones below. This device enables them to take advantage of an especially long growing season and thus produce a maximum number of seeds.As the season advances, the retreating snows are followed up the slopes of the mountains by wide expanses of flowering plants. This riot of color lasts but a short while, then is gone. The porous soil dries, the green turns red and brown, seeds are shed. The year’s growing season is over; soon the snows will come and again all will be white and silent.

Some of these small plants prefer the higher and drier meadows and they rock ridges. The commonest plants of these dry places are the Scarlet Gilia, Western Wind Flower, Jacob’s Ladder, Newberry’s Knotweed, Douglas Phlox, Sulfur Flower and Rock Penstemon. They are adapted to rocky soils poor in organic matter. Others are at home only within the moist and shaded confines of the forest. Typically, Crater Lake Currant, Wood Rush, Coralroot Orchid, Pyrola, and Pipsissewa grow from the forest humus. Still others grow only in bogs and moist meadows where they root in the waterlogged soil. Every boggy habitat supports the Bog Orchids, the Shooting Stars, and the Elephant Heads. But whether its habitat be boggy or dry, sunlit or shaded, each plant in the park must successfully meet the problem of a short growing season to survive.

Why, it may be asked at this point, has so much time and study been spent upon these small and often inconspicuous organisms? There are several answers to this question. They have been studied to satisfy a curiosity of botanists; scientists often investigate nature just for the thrill of discovering something new. These plants furnish food and protection for many birds and animals. Their root grow into the soil and prevent it from being washed away by the water. When they die their bodies add humus to the soil, enriching it and forming a small part of the huge sponge of plant material which overlays the mineral soil. The importance of this sponge cannot be overestimated. It soaks up the melting snows and so prevents excessive runoff and flood during the spring. During the dry season it releases a steady supply of pure water to men living in the lowland. Further, the steady accumulation of this same layer of plant material prepares the way for the trees and shrubs which will eventually take over the areas now supporting only the smaller forms of plant life. The extent of valuable forest land is in this way increased. Study enables us to appreciate and understand these vital functions. Seek out the services of a competent nature guide and with his aid open your eyes to the ways of the wild flowers.

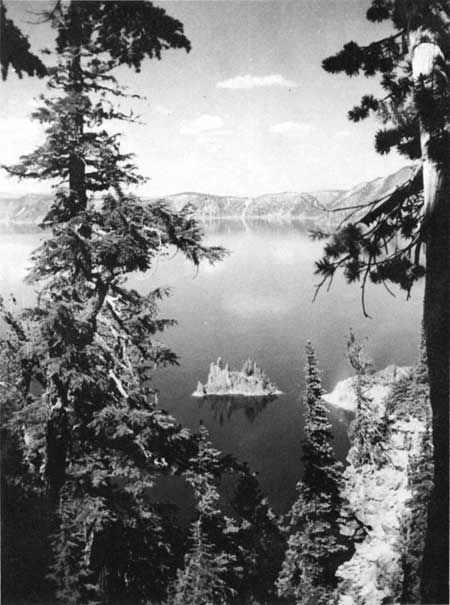

The Rim in Miniature

By Gordon Walker, Ranger-Naturalist

The idea of the Wizard Island crater being a crater within a crater has been a point of great interest to many visitors. The cartographer of the U. S. Geographical Survey maps of the region seems to have been so intrigued with the idea that he filled it with water on his map. This, of course, could not happen in view of the extremely porous sides of the cone. It is interesting to note, however, how closely the small crater does resemble the wall of the caldera in other respects.

The complete absence of snow on the northern and eastern face of the rim, while quite large quantities remain on the south and west, has often been noted. The same condition was found in mid-July in the small crater. A deep snow bank lay in a perfect crescent around the south and west bank while none remained in the bottom or on the north and east banks. The snow remained in identical pattern because the same forces were operative as those acting within the rim. Prevailing winds from the southwest blow large quantities of snow into the caldera piling up huge drifts on that side. On the opposite side the tendency is to blow the snow out of the rim wall.

The rate of melting is another factor which determines the position of the remaining snow. This in turn is dependent on the duration and intensity of the sunshine which strikes any area. Since it faces north, the south wall receives no direct sunlight for long portions of the year, and during the longer days when the sun is highest it receives only a few thinly-spread rays. The west wall receives the direct morning sun but is in the shadow during the hot afternoon sun. The east wall, which receives this hot afternoon sun, and the north wall, which is sunny almost all day all year round, have higher temperatures and lose their thinner cover of snow quickly.

On the northeast portion of the wall this quick removal of winter snow, coupled with higher temperature, enables certain plants such as yellow pine and western white pine to grow at elevations far above their normal upper limits. A circle of white barked pines, a high elevation plant which favors exposed positions, crowns the Wizard Island crater. Not too surprisingly, the only break in this circle is on the northeast side. There a single lodge-pole pine has successfully established itself slightly within the crater where it is warmed by the long hours of direct sun.

Towering Majesty

By Edwin Braun, Ranger-Naturalist

Second in grandeur only to the lake itself are Mazama’s deep forests of giant mountain hemlock. This tree is common along the rim, where it descends the basin walls to the water’s edge, and climbs the flanks of the surrounding ridges almost to timberline. It forms the main body of cover of the higher elevations of the park, extending downward into the lodgepole pine belt. It is a common and conspicuous tree, and yet because its finest stands are slightly removed from the main paths of travel, it is seldom seen in its full magnificence.

Over the greater part of its range, the mountain hemlock is a moderate-sized tree, growing to a maximum of 2-1/2 feet in diameter and 90 feet in height. Here, however, it grows to 6 feet and more in diameter and 120 to 130 feet in height in the most favored spots. These giants grown in moist, nearly level areas surrounded by dryer ridges and slopes clothed by smaller hemlock. Here the forest floor is clear of brush and clean of tangles of fallen limbs and trunks. The ground is carpeted by small green herbs and shrubs whose thin leaves glow with life in the shafts of golden sun. Beneath these small plants the deeper layer of duff is soft to walk upon, and silhouetted against them, the massive blue-gray trunks rise straight and tall in great colonnades, holding aloft a canopy of green. Butterflies and other insects flit and buzz among the slanting rays of sunshine. Here the air is still and sounds are faint and muffled. Here there is rest and peace.

Go and see these most graceful of trees at their finest. Seek them where they hide deep in the trackless forest among their lesser fellows, and feel the thrill of discovering for yourself these cathedrals of the forest.

The Extraneous and the Parks

By Dr. G. C. Ruhle, Ranger-Naturalist

Originally our national parks were set aside with an expressed purpose of protecting the outstanding and peculiar values found within them. They were essentially in primitive state and the primitive was to be cherished and preserved. At the same time limited development was to be undertaken, so that visitors might come in reasonable ease to see, learn and enjoy. But always the scientific significance, the primitive character, the ideal of sanctuary for native life, both plant and animal, and the aesthetic appeal were to fashion park policy and operation. Any departure from these standards was to be regarded as unhealthful intrusion in the parks. Cultivation of crowds for the sake of records or profit was considered as unworthy violation of principle.

Within the past few years, numbers of visitors to national park areas have mounted to staggering figures, far surpassing a score of millions annually, and with these crowds come the many who understand not, neither do they love. Theirs is not a visit for inspiration, study, and appreciation of the natural phenomena. Theirs is not respect for cleanliness and order, for propriety and fitness and decorum, for consideration of the fellow who follows, let alone for generations unborn. Their wake is marked by roadsides strewn with bottles, cartons, and refuse, by vandalism to structures and natural features, by wildfolk with lives disrupted by unnatural feeding and fraternization, by waste meadows stripped of flowers and herbage, by charred masts in lifeless forests swept by fire. With decreasing revenues and man-power, park efforts have been futile to check and to minimize the devastation. They cry of alarm is rising from those who look beyond the use of national parks for picnicking, motoring, and conventional activities.

Drastic possible measures have been proposed to curb impairment of the parks from overuse and inflated development. One hears of limitation of numbers admitted, of control of numbers of campers in campgrounds, of removal of overnight facilities to sites remote from principal features, of day-use of parks only. Some advocate a screening of admittees; it were interesting to discover what screening process and what criteria would be advocated.

It seems that greatest consideration should be given to that which is charged by law as proper use of the parks. My contention is that if we restrict attractions to the enjoyment and interpretation of the features for which the park has been set aside, the overwhelming tide of visitors will be stemmed and controlled, and the destruction of the primitive will be checkmated. This, too, is drastic, for by it such crowd impellents as ski carnivals, conventions, mass picnics, are out, as are golf links, pinball machines, and dress dinners. This means that such lures as skiing, fishing, and dancing, all laudable in their proper sphere, be reduced to an incident in, and not the purpose of a visit to a park. All “sports” inducements, such as ski lifts and competitive meets, are incompatible with proper use, as predicated by those who seek refuge in them for silence, relaxation, aesthetic inspiration and to marvel over God’s handiwork. It means further that artificialities, such as our Lady-of-the-Woods, yes, even the popular firefall in Yosemite, deserve the ban which has been put on the Rock-of-Ages ceremony in Carlsbad Cavern and on the various “bear shows” in other parks.

Crater Lake National Park has been exceptional in its resistance to the demands of a public seeking ordinary resort entertainment. Adequate, suitable divertissement of this type is and should be provided elsewhere than in a national park. We offer skiing, fishing, and similar diversions, but only as they may be the means by which one enjoys in fuller measure the natural wonders of the park. The Park Service welcomes the man who revels in wetting a fly in the singing streams of our parks while noting the exuberance of the companion ouzel, the sparkle of dancing waters, the caress of mountain breezes, the flowers nodding and dipping in the ripples, the diamond dew-drops on web and branchlet. Such a fisherman can have successful day fishing and still not catch a single fish. The Park Service beckons to the skier who delights in the wintery grandeur while gliding on langlauf through the somber forests on the mountains.

In the face of all of the serious impairment of the primitive in every national park, how can there be any question about the inadvisability of a “Come one, come all” program? Wilderness character is fragile and easily dissipated, and once lost, seems irrevocable despite our best efforts. The need for correction is urgent and delay is costly. Control what is offered to the visitor in a national park, and there will quickly be natural control of the visitor and visitor use of the park.

The Crater Lake Natural History Association

This organization was founded in 1942 to promote and assist the ranger-naturalist program, to further the investigation of subjects of popular interest and importance and to aid in the distribution of information on all subjects pertaining to the park. Toward this end it sponsors NATURE NOTES and makes the following publications available for purchase:

| A Field Guide to Western Birds, Roger Tory Peterson | $2.75 |

| A Manual of the Higher Plants of Oregon, Morton E. Peck | 5.00 |

| Birds of Oregon, Ira N. Gabrielson and Stanley G. Jewett | 5.00 |

| Meeting the Mammals, Victor H. Cahalane | 1.75 |

| Forest Trees of the Pacific Slope, Sudworth | 1.25 |

| Wildlife Portfolio of the Western National Parks, Dixon | 1.25 |

| Your Western National Parks, Dorr Yeager | 3.50 |

| Oh Ranger!, Albright and Taylor | 3.00 |

| Topographic Map of Crater Lake National Park, (U.S.G.P.I.) with geological sketch by Francis T. Marthes |

.40 |

Your membership in the association would greatly aid the furtherance of these worthwhile purposes as well as bring you NATURE NOTES without charge. A liberal discount is given to members on all except government publications. The annual membership fee is $2.00.

Other pages in this section