Volume 15, September 1949

All material courtesy of the National Park Service. These publications can also be found at http://npshistory.com/

Nature Notes is produced by the National Park Service. © 1949

When Succession Skips a Beat

By Bruce R. Brandell, Ranger-Naturalist

Plant succession and life-zoning are two striking phenomena at Crater Lake. The former is the transition of plant life in a given location from the simplest forms that appear first to the final, complex flora, or climax vegetation. Theoretically, the process of succession follows a definite pattern, with a sequence from lower to higher types of life as the area changes. It is noteworthy that nature often skips some steps as she clothes a mountain.

The park is an excellent place to observe succession of plant types because of the variation of soil conditions from bare rock to relatively great fertility. The process of replacement from the predominance of simple to higher plants is essentially one of breaking the rock down into ever finer particles and enriching it with organic matter so that the latter can exist. This process usually begins with lichens, which come in various colors, ranging from black thru green, yellow, orange, to red. The green, stringy staghorn lichen and the woolly squaw-hair, frequently miscalled mosses, are common varieties of tree lichens. The unusual feature of lichens is that they are actually two plants, an alga and a fungus, growing together. The fungus forms the main body of the lichen, providing it with protection and anchoring it to the rock or tree. Scattered through it the green algal cells contain chlorophyll and manufacture food for the lichen. Such co-operation between organisms is called symbiosis.

Rock lichens are able to decompose enough rock material by their secretions to gain a foothold. Each of thousands of generations of lichens grow, do their bit to disintegrate the rock, then die and contribute a minute amount of organic material. Finally a sufficient amount of soil collects to support mosses. Patches of moss may be found wedged in a protected rocky niche on top of a layer of soil three or four inches thick.

Rock garden plants then take their turn. One of the pioneers is Jacob’s ladder, which has small blue flowers with rows of opposite leaves that suggest the rungs of a ladder. These usually occur in the same sites as the patches of moss, as if they had merely exchanged places. Another plant that loves rocky chinks is the western windflower, conspicuous for its white, petal-like sepals and cluster of many stamens and pistils. This blooms in the park in early July. Indian paintbrush, familiar to many, takes its place on the rocky cliffs with its pale orange to reddish bracts that look like a brush dipped into red paint. Also appear the rock loving penstemons, which have red or purplish funnel-shaped flowers.

Normally these wild flowers are followed by woody herbs, the more common and conspicuous of which are the serviceberry, red elderberry, and mountain ash. The flowers of all three are white, but are arranged quite differently. The serviceberry has solitary flowers, subtended by a leaf, and the plant has simple leaves. Both the ash and elderberry flowers are in heads which can easily be distinguished from each other. The flower clusters of the mountain ash are divided into sub-clusters in which the outer have the longer stalks and are attached farther down the stem. This arrangement is technically known as a panicle. Both shrubs have pinnately compound leaves. The climax plants in most areas of the park are evergreens, the type differing with life zones.

The actual process of succession may have omissions and substitutions. On the pumice flats, for example, apparently the lichen and moss stages are omitted; organic material and soil may be brought in by wind and water. As the pumice itself is reduced by weathering certain plants appear without the orderly succession as related above. Soil building is sometimes followed directly by whitebark pines. In another situation, such as a damp area near a stream, ferns, sedges, and grasses may be inserted between the moss and wildflower stages.

Plant succession can also be observed in forest areas that have been burned. On such areas hardy shrubs must enrich the soil before it can again support the plant life that was destroyed. Thus, in the plant successions at Crater Lake, we may see how soil is formed, the evolution of plant cover, and the ways of primitive vegetation on this once rocky earth of ours.

Identification of Lake Fish

By P. H. Shepard, Ranger-Naturalist

Confusion as to the identify of Crater Lake fish is apparently a result of the colloquial terminology, poor stocking records, and changes in the fish when land-locked. The name “silversides” is usually applied to the sockeye salmon Oncorhynchus merka, but is often confused with silver salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch. If silver salmon are reproducing in Crater Lake, in which there has been no stocking since 1940, it would apparently be the first case on record of land-locked kisutch reproducing; otherwise the silver may be gone from the lake.

Three species were reported stocked in the lake; they are the sockeye, the silver salmon, and the rainbow trout. Dr. John Raynor, ichthyologist of the Oregon State Fish & Game Department, identified the fish being caught now as sockeye and rainbows, and at least two other authorities, including Dr. Carl Hubbs, have independently agreed with Dr. Raynor’s identification of the lake fish.

Nivation

When the amount of snow that falls in a region does not all melt during the year the accumulation may result in a permanent snowfield, a mass of ice, or a glacier. In the case of ice, the term glacier is not applied until the mass has reached the moving stage. The transition from snow to ice is brought about largely by the end of winter the usual snow bank is no longer composed of flakes or pellets of snow; instead it is a mass of granular ice to which the term neve is applied.

Where neve fields increase in thickness from year to year eventually the pressure compacts the lower portion of the mass into more or less solid ice; if the mass begins to move the name glacier is applied. Thus a glacier, at least at its source, has a stratification; snow overlies neve which in turn grades downward into more solid ice.

In Crater Lake National Park so little snow lasts through the summer under the present climate that solid ice usually does not form. However, the small amounts of snow that last through the summer as well as the snow that lingers until last June, July or August has been converted into neve. These patches of neve which last into or through the summer exert a limited though definitely noticeable weathering and erosional action.

On nearly level land the geological evidence of neve action (nivation) is perhaps most noticeable. Where neve lasts well into the summer, year after year, the site of the neve is lowered below its surroundings and a small depression is formed. Early in the summer season the accumulation of melt water at the base of the neve during the day is converted into ice at night only to be remelted the next day as more water trickles downward from the overlying neve. This repeated freezing and thawing acomminutes the rock particles. Some water drains downward through the mantle and out of the depression and carries away the finer rock particles. In this manner the depression is enlarged and deepened by the same process of nivation that inaugurated it.

On a sloping terrain nivation often is more active although its evidence may be difficult to distinguish from that of normal erosion. Its results may resemble those of slides and creep phenomena. As nivation continues on a slope the resulting concavity or niche approximates a cirque in appearance although hardly in size. On bedrock nivation operates more slowly than on mantle although the results are similar.

In the higher portions of Crater Lake National Park, nivation is an important and evident geologic process. In the forests and at the base of the talus slopes within the caldera the evidence is not so apparent, but on the treeless expanses there exist many noticeable areas. Several representative examples border the highway from Park Headquarters in the Rim Village near its upper end. These rather flat, treeless expanses are concave upward as a result of greatest activity near the center of the neve field, which in 1949 lasted well into July.

On the back slope of Llao Rock, numerous areas of nivation are easily identified. Some are occupied by neve so late into the summer that practically no vegetation occupies them although along their margins soil and grass cover the pumice at the edge of active nivation. At several localities small serpentine ridges (of) dust-like material were observed on melting of the neve. These ridges, two to four inches high, were also traceable under the neve and marked the egress of streams or rivulets of melt water. Although it is known that rodents dig trails under the snow and neve these were not burrows near the observed ridges. Instead the tiny ridges were composed of water-carried and water-deposited material. In effect they were eskers on a very minute scale.

Numerous forest-free slopes on the higher elevations in the park are the sites of active nivation. Downwards these sites grade into areas which posses similar appearing characteristics and which are believed to have been subject to nivation during past periods of heavier snowfall. On steeper slopes facing both inward and outward in respect to the caldera, nivation is believed to be an active geological agency whose results are largely obscured or exceeded by creep and slide. The small ridges of water-deposited silt are identified as esker-like features produced by sub-neve runoff.

The Frozen Lake

By Franklin C. Potter, Ranger-Naturalist

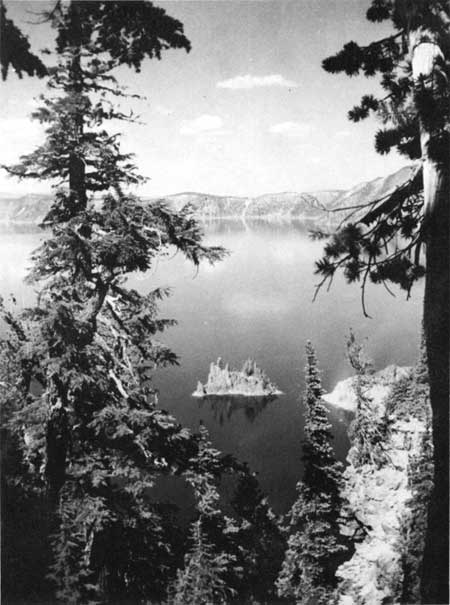

The biggest news of the year from Crater lake is that its surface froze solid in the winter of 1949. The lake that pamphlets said would never freeze because it was too deep has frozen; and, moreover, stayed frozen for almost three months.

An examination of the winter weather reports since 1926 reveals that the lake had never frozen during that time. However, in The Providence Manual of Information, compiled by the ranger-naturalist staff of 1934, H. H. Waesche reported that the lake was frozen over for two days in 1924. He adds that E. I. Applegate “suspects” that it was frozen at times during the winter of 1897-98 when the temperature at Fort Klamath reached -42° F. Although the lake often has skim ice sometimes over its whole surface, its resistance to freezing is due to the heat reservoir in the immense volume of water.

During the past winter the mean temperatures were lower than ever recorded. December had a mean temperature of 19, January 18, and February 22. The extremes were -9 December, -14 in January, and -8 in February. Considering that only eight out of 17 past winters had weather below zero, it was a cold winter on Mount Mazama.

A limnological survey of Crater Lake revealed that temperature stratification of the lake occurs at about 200 feet. Below that depth the water remains perpetually at 38 degrees. In the upper 100 feet the water temperature varies from 32 to 67, depending upon external factors; the highest temperature is near shallow shores. One reason that the lake fails to warm under the summer sun is a lack of suspended material which would absorb heat and warm the surface water. Because water becomes denser as it cools to 38 in colder weather there is some turnover in the upper layer, the warmer water rising from below. As the surface is cooled below 38 it becomes less dense and the water below imparts heat toward the surface, retarding ice formation. Crater Lake, with its great depth, stores a large amount of heat, even in water of 38 degrees.

This past winter a long period of abnormally low temperatures forced the upper water strata down to 32 degrees and the surface even lower. Heat absorption from the lake by the air was faster than convection of heat from the depths. Ice first appeared around the shoreline and gradually grew towards the center of the lake. After the surface was solid heavy snowfalls deposited four feet of snow on the two inches to one foot of ice. Now that it is known that the lake can freeze under certain conditions, another delicate environmental balance is added to those which determine the character of the mountain and the lake.

The Little Beggars are Scarce

Young of the year came out of maternal burrows in the rim area during the first week of August, 1949, in numbers much under modal, and gave no support to the theory that a rather sparse population of adults is necessarily favorable to population replenishment. In 1947 squirrels were so plentiful on highway 230 that they constituted a driving hazard. This year the area is so largely deserted that it must be concluded that squirrel scarcity is a more than local phenomenon. Be that as it may, the individuals that are with us are acting as though they are convinced that lean squirrel years need not necessarily produce lean squirrels. The golden-mantled ground squirrel, which certainly affords park guests as great an amount of entertainment and opportunity for behavior study as any member of our wildlife group, was only moderately common during the 1949 season. Good indicators of the size of the squirrel population are the maximum number of squirrels that can be seen at one time at the head of the Lake Trail and the number of squirrels resident in the upper part of the Rim Camp area. To see twelve squirrels at a time at the head of the Lake Trail, and all of them big ones, means a big park population. Sample observations made during 1949 gave the writer an eight squirrel maximum and a mode of four. Some of the squirrels were yearlings and one was even a young of the year. No such callow operative could have maintained a pitch there during the roaring 30’s. He wouldn’t have lasted an hour. One squirrel only has been around the upper Rim Camp area.

Young of the year came out of maternal burrows in the rim area during the first week of August, 1949, in numbers much under modal, and gave no support to the theory that a rather sparse population of adults is necessarily favorable to population replenishment. In 1947 squirrels were so plentiful on highway 230 that they constituted a driving hazard. This year the area is so largely deserted that it must be concluded that squirrel scarcity is a more than local phenomenon. Be that as it may, the individuals that are with us are acting as though they are convinced that lean squirrel years need not necessarily produce lean squirrels. The golden-mantled ground squirrel, which certainly affords park guests as great an amount of entertainment and opportunity for behavior study as any member of our wildlife group, was only moderately common during the 1949 season. Good indicators of the size of the squirrel population are the maximum number of squirrels that can be seen at one time at the head of the Lake Trail and the number of squirrels resident in the upper part of the Rim Camp area. To see twelve squirrels at a time at the head of the Lake Trail, and all of them big ones, means a big park population. Sample observations made during 1949 gave the writer an eight squirrel maximum and a mode of four. Some of the squirrels were yearlings and one was even a young of the year. No such callow operative could have maintained a pitch there during the roaring 30’s. He wouldn’t have lasted an hour. One squirrel only has been around the upper Rim Camp area.

Ornithological Notes of Interest

Passing observation was made of a number of bird species during the 1949 season. Rosy finches were seen near the top of Garfield Peak Trail and on Cloudcap on several occasions and during the last week of July a parent was seen feeding two birds of the year. The hunger cry of these proved to be quite musical and a pleasant change from the bleats of young robins and squawks of petitioning nutcrackers so commonly heard in the Rim Camp.

On August 5th a flock of about 20 large finches was feeding along the edge of the crater of Wizard Island. They moved rapidly but ultimately one bird perched within about forty feet and in full view of the binoculars. It appeared to be a female pine grosbeak, and the undulating flight of the flock as it crossed Skell Channel presented additional evidence in favor of the identification.On August 4th two golden eagles were soaring over Garfield Peak and the next day an immature bird was seen over the rim drive behind Llao Rock. Golden eagles were seen over Garfield again on August 13 by the morning field trip party. When seen in the park, they are more often observed in the area along the rim between Garfield and Applegate Peaks than elsewhere. Consequently, this area is called Eagle Crags. Although both bald and golden eagles have been seen along the rim, recent nesting records here are of bald eagles which bred seven years ago on Wizard Island. No bald eagles were reported this year.

Rock wrens, unreported during the 1948 season, were present on the large talus slope underneath the Garfield Peak trail. Singing birds were heard there during the second week in July. In past seasons these handsome little rock dippers have been common inside the rim, their pleasant song rising to greet the Sinnott Memorial attendant on his arrival.

During our stay in the utility area at headquarters we heard more than the usual number of olive-sided flycatchers. In the same locality during the first week of July, Audubon Warblers were present in considerable numbers but no other warbler species were heard or seen.

From the rim viewpoint just west of Hillman Peak, ravens have been observed a number of times during the summer. Past observations strengthen an assumption that these large corvids nest within the rim. During June and July a company of four, probably a family group, have been seen casually along the rim from the lodge to the Devil’s Backbone, sometimes flying over the Rim Village or wandering down Munson Valley. The hoarse croak and the long pointed wings distinguish the ravens from their close relatives, the crows, and the ranges of the two birds seldom overlap.

Besides those of golden eagles there have been some other interesting notes on birds of prey this summer. The red-tailed hawk has previously been reported nesting in upper Munson Valley, and evidently did so again this year. At least one immature red-tail wandered about the valley near park headquarters. It was seen several times during July and August, giving the hunger cry almost constantly and being besieged by robins, tanagers, and jays. The falcons reported annually to nest in Llao Rock are prairie falcons. A family group of two immature birds and an adult were observed near the base of the Rock on July 27, the young giving the hunger call. During the afternoon of Saturday, August 13th, one of the juvenile birds perched on a hemlock by the Sinnott Memorial for about 15 minutes. A crowd of park visitors collected on the walk in front of the Information Building, and there was ample opportunity to identify with field glasses this strikingly light-colored, dark-eyed falcon, whose plumage contrasts to the dark color of the duck hawk. Although the latter nests typically near a body or stream of water, the paucity of waterfowl and shorebirds on the lake would suggest that these falcons depend largely on small mammals for food, as would be expected of prairie falcons. One member of this family group was observed soaring on the outside of the rim on August 4th.

During the latter part of August and early September a rather extensive migration of hawks passed through the park. When northwest winds prevailed, creating thermals on the west slopes, the fire lookout on Scott Peak reported scores of hawks of several species passing all day long. Notable among them were goshawks, marsh hawks, and a number of eagles.

The handsome state bird of Oregon, the western meadowlark has been seen again in the meadow east of the lodge, this year on July 8th. Post nesting dispersal probably accounts for the singular appearance of the only member of the blackbird family that has been reported from the rim area during the summer. As winter approaches the meadowlark gathers in small flocks and move down into sheltered valleys. like the eastern meadowlark, it’s mellow, fluted notes may be heard in fields any month of the year. It is not to be confused with the true larks, of which the western representatives are the horned larks. Another family, the pipits, have a member known commonly as the “American skylark.”

Adventures with Park Amphibians

The average visitor to Crater Lake National Park is oblivious of the amphibian population in the vicinity of the lake; and the statement that frogs are numerous behind park headquarters or that salamanders abound at the lake edge seldom fails to bring an expression of surprise. “I’d have thought it was too cold up here for frogs and salamanders.” Amazing as it may seem, Crater Lake has a large representation of these lowly creatures that seem to thrive in the cold, for several of our species are found only at high altitudes.

Soon after my arrival in the park I was surprised to hear croakings coming from the marsh behind park headquarters. The marsh was still largely covered by snow and it was difficult to believe that frogs were active so early in the season. I fitted myself with a light and investigated. Following up the course of one of the streams, I discovered a female frog squatting in a hole under the opposite bank. Later I located two males by their croaking. In spite of the cold that numbed my hands these amphibians were quite agile. I collected them, and then, to my utmost surprise, I found several egg masses. These frogs were not only out and active, they were breeding! Identification showed my specimens to be Cascade frogs, Rana cascadae, an inhabitant of high altitudes in the Cascades.

I revisited the egg masses the following day. Each egg was about one-third inch in diameter, with transparent coats and a dark embryo in the center. A single mass consisted of several hundred eggs, all encased in jelly. I watched their development during the next few days as the embryos increased in size and became motile within their coats. On the 9th day the tadpoles freed themselves of the encumbering egg coat to take up a free life in the stream.

The same night I found the Cascade frogs, I flashed my light into a small burrow in the marsh and saw a white throat swelled out to the size of a marble. I recognized a Pacific tree frog, Hyla regilla. It was truly a shock to find this pretty little fellow out so early in the season, for I was accustomed to collect them in the San Francisco region in temperatures far higher than those associated with freezing nights and melting snows. This Hyla is a jewel among frogs with his vivid green back, white throat and belly, and black eye patch. On the end of each toe is an adhesive disk to serve in climbing, enabling him to walk up a pane of glass. In spite of his small size, only an inch from snout to vent, Hyla has a mighty voice. He puffs out his throat and emits a bleat that may be heard a half mile away. Later I saw several of these frogs among the boulders in Wizard Island, but they were so adept at diving into crevices that I was unable to capture a specimen.

The common northwestern toad, Bufo boreas boreas, is abundant in the Rim Area, but this member of the clan is so familiar to most everyone that it is unnecessary to discuss him here.

The salamanders of Crater lake are probably the most interesting of the Amphibian inhabitants. Although salamanders show a superficial resemblance to lizards it has been said that they are no more closely related to them than we are. The more apparent differences between the two is that a lizard has scales and lives in dry places, whereas a salamander dies if subjected to drying. Salamanders are more sluggish than most lizards and must deposit their eggs in water and pass the first stage of life as gilled larvae. The anatomical differences between them are most striking of all, but are principally significant to specialists.

The two species of salamanders found at Crater Lake are taken under stones at the water’s edge where they live, apparently harmoniously, together. The more numerous type is the Crater Lake newt, Triturus granulosus mazamae, which has been taken only at Crater Lake. He is black, about eight inches long, with granular skin and a brilliant orange underside. His less-common companion is the long-toed salamander,Ambystoma macrodactylum, named for his unduly long digits. He also is black except for a line of yellow down the back; his skin is smooth and glistening.

In the middle of July an overturned rock revealed these animals in knots of five or six individuals all clinging together. The ratio was about ten Triturus to one Ambystoma.Considering the greater agility of the latter, I had far more Triturus to show for my efforts than Ambystoma. It is of interest to note that a search under the rocks on the first of July had failed to reveal any specimens. Thus, they must have congregated there sometime between the first and the middle of the month. It is my presumption that they winter under logs, rocks, and other objects away from the lake shore, and gather nearer the water for breeding.

An Historical Passage

For a long time it had been contended that Crater lake never freezes, that what seemed to be ice was illusory, and that even in summer under certain optical and atmospheric conditions, the surface appears to be covered with skim ice. Nice explanations were given for the improbability of the Lake’s ever freezing. New explanations are in order now, for this year, definitely, the lake not only was completely covered by a sheet of ice, but this ice was strong enough to support a significant blanket of snow. For over two months, from mid-February until May, park visitors beheld a white expanse in place of the sapphire sea so justly famous.

To obtain scientific data, to forestall stunt-loving publicity seekers, and to reconnoiter for information of importance in meeting situations of emergency, Superintendent E. P. Leavitt authorized Acting Chief Ranger Duane S. Fitzgerald and me to descend the caldera wall. Both of us had much experience with snow travel and operations in extreme cold; both had attended special schools of mountain climbing and are qualified as instructors. For two months we had watched the ice gradually sheeting the surface. Already early in the year, Grotto Cove and Skell Channel were completely encased and were receiving a deep blanket of snow. Ice formed elsewhere on the shore and the growing shelves encrusted more and more of the deep blue waters. By February 13th, only three patches of open water remained with a total area of a square mile. Late that week, these too were closed, and more and more snow collected on the surface. While intently watching the freezing, we commented on its significance, and finally determined to investigate the cover at close hand. The date picked for descent was March 14.

Instead of a beautiful clear day, sullen skies disappointed us. We waited through the morning with no bolster to hopes. As the time was passing, it was decided to reconnoiter and prepare fuller plans for a more suspicious day. Our first attempt was to reach Discovery Point in the park snowcat, so that we could take advantage of the sloping caldera walls and the ice pack on Skell Channel. But hazardous snow stopped passage of our specialized vehicle. We returned to the rim-road wye to study critical slopes, slippage, depth, and sustaining loads of snow inside the wall. Equipped with snowshoes and ropes, we gingerly experimented and tried out our aids. I personally investigated the feasibility of descent thru a forested strip, and discovered that while in some places I could sink to my neck if without snowshoes, the method proved perfectly possible. Attempts to climb back up were very arduous, being made possibly only by use of brute strength. I tried my wings a little more thoroughly and the thought flashed thru my mind, “Do it now,” and I was off with snowshoes strapped on my back. Ranger Fitzgerald above, seeing me make good headway down the strip followed in my trail but left his snowshoes near the rim. While twice the route had to zig-zag cautiously across an open col, no great avalanches of snow were precipitated. At the foot of the slopes, a twenty-foot andesite cliff had to be traversed by rappelling on an anchored rope. We reached the lakeshore at the boat landing. It was found that snow on the ice was eight to twelve inches deep, and that the ice readily supported our weight. I set out on snowshoes in a direct line for Wizard Island but Fitz discovered the snow too deep for good progress without his aid. Several hundred feet from shore the ice began to crack and rumble ominously and numerous tests were made of its strength. Finally, about one thousand yards out, under a cover of only four inches of snow, I succeeded in chopping thru the ice, and with my thumb and index finger, estimated it to be two inches thick. The hole was enlarged to admit a snowshoe, which could be shoved three to four feet into the water beneath. This confirmed that the ice cover was on the lake water itself, and not over a pocket of surface ice. The lake is over 1000 feet deep at this place. With the disturbing information, I started a diagonal retreat westward and shoreward, only to assay again and then again on a due course to the island. This maneuvering brought me several hundred yards west of the tip of the lava flow by the island boathouse, and a hurried finish was made to the trip.

I climbed ashore, visited the boathouses, and snowshoed to the base of the main cinder cone. Little of note was observed. There were no birds and no tracks nor sounds of wild folk. Utilizing knowledge gained, the return trip was considerably shortened.

Meanwhile Fitz had plodded a half mile or more thru sodden snow from the landing. Upon reaching him, I gave him my snowshoes so that he could continue on to the island. Traveling nearer the shore, at one place he discovered ice pushed shoreward that was a foot in thickness. Estimates of snow depth near the shore were of the nature of several feet. In my continuing on to the landing it was noteworthy that I found each of Fitzgerald’s footprints to be completely filled with watery slush.

The real struggle lay ahead – the struggle up the rim. It took two hours of obstinate persistency and both of us were completely exhausted by it. A few hundred feet from the rim, the sun suddenly broke thru the clouds, and permitted taking a few photographs. Probably because of the limited number of years past that the road has been plowed, during which the lake never has frozen solid, and because of the handful of winter visitors before that arduously struggled to reach the lake in winter on snowshoes or skis, this is the first known crossing of Crater Lake on ice. Its justification as summarized for the press by Superintendent Leavitt, was in the interest of science, and as a result the park has gained valuable data.

The Crater Lake Natural History Association

This organization was founded in 1942 to promote and assist the ranger-naturalist program, to further the investigation of subjects of popular interest and importance and to aid in the distribution of information on all subjects pertaining to the park. Toward this end it sponsors NATURE NOTES and makes the following publications available for purchase:

| A Field Guide to Western Birds, Roger Tory Peterson | $2.75 |

| A Manual of the Higher Plants of Oregon, Morton E. Peck | 5.00 |

| Birds of Oregon, Ira N. Gabrielson and Stanley G. Jewett | 5.00 |

| Meeting the Mammals, Victor H. Cahalane | 1.75 |

| Forest Trees of the Pacific Slope, Sudworth | 1.25 |

| Wildlife Portfolio of the Western National Parks, Dixon | 1.25 |

| Your Western National Parks, Dorr Yeager | 3.50 |

| Oh Ranger!, Albright and Taylor | 3.00 |

| Topographic Map of Crater Lake National Park, (U.S.G.P.I.) with geological sketch by Francis T. Marthes |

.40 |

Your membership in the association would greatly aid the furtherance of these worthwhile purposes as well as bring you NATURE NOTES without charge. A liberal discount is given to members on all except government publications. The annual membership fee is $2.00.

Other pages in this section