An Historical Passage

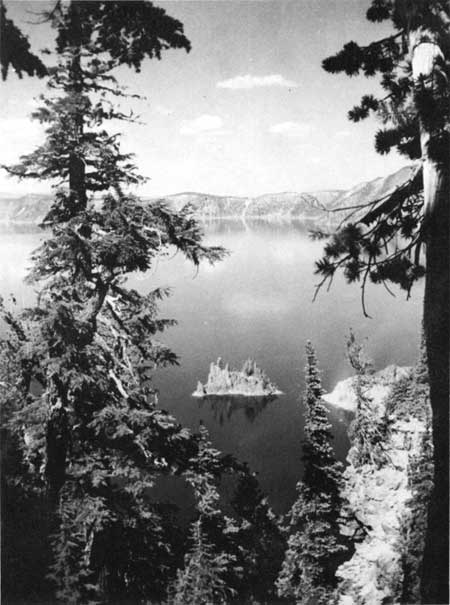

For a long time it had been contended that Crater lake never freezes, that what seemed to be ice was illusory, and that even in summer under certain optical and atmospheric conditions, the surface appears to be covered with skim ice. Nice explanations were given for the improbability of the Lake’s ever freezing. New explanations are in order now, for this year, definitely, the lake not only was completely covered by a sheet of ice, but this ice was strong enough to support a significant blanket of snow. For over two months, from mid-February until May, park visitors beheld a white expanse in place of the sapphire sea so justly famous.

To obtain scientific data, to forestall stunt-loving publicity seekers, and to reconnoiter for information of importance in meeting situations of emergency, Superintendent E. P. Leavitt authorized Acting Chief Ranger Duane S. Fitzgerald and me to descend the caldera wall. Both of us had much experience with snow travel and operations in extreme cold; both had attended special schools of mountain climbing and are qualified as instructors. For two months we had watched the ice gradually sheeting the surface. Already early in the year, Grotto Cove and Skell Channel were completely encased and were receiving a deep blanket of snow. Ice formed elsewhere on the shore and the growing shelves encrusted more and more of the deep blue waters. By February 13th, only three patches of open water remained with a total area of a square mile. Late that week, these too were closed, and more and more snow collected on the surface. While intently watching the freezing, we commented on its significance, and finally determined to investigate the cover at close hand. The date picked for descent was March 14.

Instead of a beautiful clear day, sullen skies disappointed us. We waited through the morning with no bolster to hopes. As the time was passing, it was decided to reconnoiter and prepare fuller plans for a more suspicious day. Our first attempt was to reach Discovery Point in the park snowcat, so that we could take advantage of the sloping caldera walls and the ice pack on Skell Channel. But hazardous snow stopped passage of our specialized vehicle. We returned to the rim-road wye to study critical slopes, slippage, depth, and sustaining loads of snow inside the wall. Equipped with snowshoes and ropes, we gingerly experimented and tried out our aids. I personally investigated the feasibility of descent thru a forested strip, and discovered that while in some places I could sink to my neck if without snowshoes, the method proved perfectly possible. Attempts to climb back up were very arduous, being made possibly only by use of brute strength. I tried my wings a little more thoroughly and the thought flashed thru my mind, “Do it now,” and I was off with snowshoes strapped on my back. Ranger Fitzgerald above, seeing me make good headway down the strip followed in my trail but left his snowshoes near the rim. While twice the route had to zig-zag cautiously across an open col, no great avalanches of snow were precipitated. At the foot of the slopes, a twenty-foot andesite cliff had to be traversed by rappelling on an anchored rope. We reached the lakeshore at the boat landing. It was found that snow on the ice was eight to twelve inches deep, and that the ice readily supported our weight. I set out on snowshoes in a direct line for Wizard Island but Fitz discovered the snow too deep for good progress without his aid. Several hundred feet from shore the ice began to crack and rumble ominously and numerous tests were made of its strength. Finally, about one thousand yards out, under a cover of only four inches of snow, I succeeded in chopping thru the ice, and with my thumb and index finger, estimated it to be two inches thick. The hole was enlarged to admit a snowshoe, which could be shoved three to four feet into the water beneath. This confirmed that the ice cover was on the lake water itself, and not over a pocket of surface ice. The lake is over 1000 feet deep at this place. With the disturbing information, I started a diagonal retreat westward and shoreward, only to assay again and then again on a due course to the island. This maneuvering brought me several hundred yards west of the tip of the lava flow by the island boathouse, and a hurried finish was made to the trip.

I climbed ashore, visited the boathouses, and snowshoed to the base of the main cinder cone. Little of note was observed. There were no birds and no tracks nor sounds of wild folk. Utilizing knowledge gained, the return trip was considerably shortened.

Meanwhile Fitz had plodded a half mile or more thru sodden snow from the landing. Upon reaching him, I gave him my snowshoes so that he could continue on to the island. Traveling nearer the shore, at one place he discovered ice pushed shoreward that was a foot in thickness. Estimates of snow depth near the shore were of the nature of several feet. In my continuing on to the landing it was noteworthy that I found each of Fitzgerald’s footprints to be completely filled with watery slush.

The real struggle lay ahead – the struggle up the rim. It took two hours of obstinate persistency and both of us were completely exhausted by it. A few hundred feet from the rim, the sun suddenly broke thru the clouds, and permitted taking a few photographs. Probably because of the limited number of years past that the road has been plowed, during which the lake never has frozen solid, and because of the handful of winter visitors before that arduously struggled to reach the lake in winter on snowshoes or skis, this is the first known crossing of Crater Lake on ice. Its justification as summarized for the press by Superintendent Leavitt, was in the interest of science, and as a result the park has gained valuable data.

The Crater Lake Natural History Association

This organization was founded in 1942 to promote and assist the ranger-naturalist program, to further the investigation of subjects of popular interest and importance and to aid in the distribution of information on all subjects pertaining to the park. Toward this end it sponsors NATURE NOTES and makes the following publications available for purchase:

| A Field Guide to Western Birds, Roger Tory Peterson | $2.75 |

| A Manual of the Higher Plants of Oregon, Morton E. Peck | 5.00 |

| Birds of Oregon, Ira N. Gabrielson and Stanley G. Jewett | 5.00 |

| Meeting the Mammals, Victor H. Cahalane | 1.75 |

| Forest Trees of the Pacific Slope, Sudworth | 1.25 |

| Wildlife Portfolio of the Western National Parks, Dixon | 1.25 |

| Your Western National Parks, Dorr Yeager | 3.50 |

| Oh Ranger!, Albright and Taylor | 3.00 |

| Topographic Map of Crater Lake National Park, (U.S.G.P.I.) with geological sketch by Francis T. Marthes |

.40 |

Your membership in the association would greatly aid the furtherance of these worthwhile purposes as well as bring you NATURE NOTES without charge. A liberal discount is given to members on all except government publications. The annual membership fee is $2.00.

***previous*** — ***next***