Volume 17 Special Number 1, 1951

All material courtesy of the National Park Service. These publications can also be found at http://npshistory.com/

Nature Notes is produced by the National Park Service. © 1951

Preface

The author, Dr. Ralph Ruskin Huestis, during his summer vacations, has served, with several breaks in continuity, as a ranger naturalist in Crater Lake National park since the middle thirties. He was born in Bridgewater, Nova Scotia, on January 14, 1892, and received his BSA degree from McGill University in 1914. From 1914 to 1919 he served with the Canadian Expeditionary Forces. Entering the University of California for graduate work, he received a Master of Science degree in 1920, and completed his work for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in 1924. At the same time, he served as assistant biologist at Scripps Institute in California. Since 1924, he has been a member of the faculty of the University of Oregon, and is now a professor of biology at that Institution. Professor Huestis has been celebrated for his ability to make natural history interesting, for interpreting science and scientific subjects in a language that the layman appreciates. This special bulletin is a reflection of that ability as well as a fine contribution to our knowledge of one of the most fascinating small mammals of the Park fauna.

“Rim wall in front of Information Building” as seen through the view window of the same.

The Golden-Mantled Ground Squirrel in Crater Lake National Park

The golden-mantled ground squirrel, Citellus lateralis chrysodeirus Merriam, is one of the commonest mammals in Crater Lake National Park and probably produces more entertainment for visitors than all other types combined. This is not only because these animals are aggregated along the rim and in the campgrounds, where the greatest concentration of visitors takes place, but also because the squirrels are handsome in appearance, readily conditioned to the presence of human beings, and both appealing and comical in their behavior.

This species is commonly present in forested regions of Oregon from the Cascade mountains eastward and is especially prevalent in the ponderosa pine forests of the Cascade, Blue, and Wallowa Mountains. It is found, in these regions, from the edge of the sagebrush up into the white-bark pines at 8000 feet altitude. At Crater Lake these squirrels are present in all regions of the park including both Wizard Island and, on one occasion, on the Phantom Ship. The race occupying the Siskiyou mountains and therefore present in the Oregon Caves National Monument is described as subspecifically distinct and called the tawney-mantled ground squirrel, Citellus lateralis trinitatus Merriam.

DESCRIPTION

The golden-mantled ground squirrel is a chunky little animal with a body about seven inches long and a well furred tail somewhat more than one-half the body length. Its legs are rather short and its ears relatively small but held tautly erect. The eyes are quite large for a burrowing animal and their size, combined with the erect carriage of the ears, give these squirrels an air of alertness and intelligence.

The flanks, the underside of the tail, and the head and shoulders are colored a rich, reddish brown. This is the coloring that accounts for the name golden-mantled. The back carries a broad median gray stripe, on each side of which are narrower contrasted stripes of black and white; two black ones with a white stripe between them. These contrasted stripes following the curve of the back while the squirrel sits up add greatly to its appearance.

“. . . contrasted stripes following the curve of the back . . .” |

Ground squirrels are not very fast animals and this squirrel compares unfavorably in speed with the chipmunks that occupy the same territory and with small enemy carnivores like the Cascade weasel, the Pacific marten, and the Cascade red fox. There is, however, an alertness in its postures and a briskness and energy in its movements that visitors find attractive. It seems probable that the hurried gallop from point to point which the squirrels alternate with a frozen pose or a brief nosing of the ground is highly adaptive. An animal in motion is likely to be seen and had better hurry if it moves at all. In addition, the time spent on exposed territory and between feeding periods is reduced to a minimum. These points may not be obvious to visitors, but they do see a hard-working little animal and admire the display of energy.

Comedy is supplied by the fact that the air of brisk alertness is not accompanied by any real evidence of great intelligence. In fact Citellus not infrequently plays the role of a busy fool; searching industriously for peanuts in empty hands when full ones beckon, and taking the trouble to investigate with a passing sniff any little object which may lie in his pathway on the rim walk pavement. He easily changes, too, from assured approach to precipitous flight with his tail above his back at about the angle a stove lifter projects from the lid, his broad little hams twinkling as his short hind legs spurn the dust.

“Comedy is supplied by the air of brisk alertness . . .” |

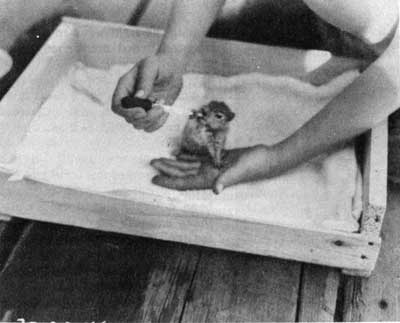

Golden-mantled ground squirrels are said by Vernon Bailey to have but one brood a year of four to six or more young. Grinnell found an average of five young in five females in Yosemite National Park. The number probably increases with the age of the mother and as fully adult females have ten functional mammae they could easily accommodate larger broods. In 1936 a mother squirrel was observed moving nine little ones from a burrow in the rim campground and in 1938 the accidental death of a mother squirrel was followed by the exit of eight hungry little squirrels which were adopted and fed by rim campground visitors. Young are reported by Vernon Bailey to be born late in June or early in July. This checks with observations at Crater Lake National Park where in both 1937 and 1938 young squirrels emerged from burrows along the rim during the first week in August. The adopted brood mentioned in the previous paragraph seemed to be about three weeks old on August the eighth. A small newly-emerged squirrel was seen coming out of a burrow in the rim campground as late as September 3, 1937.

“. . . searching industriously for peanuts . . .” |

The episode mentioned above in which a mother squirrel moved young from a burrow, part of which had been collapsed by a car, shows that these animals share the typical mammalian habit of moving young to less menaced positions. In August 1938 Dr. Fred Miller, park physician, observed the moving of six young from a nest somewhere in the Community House through the door to a refuge somewhere outside the building. The young were carried by the body with ventral surface toward the mother’s mouth and curled around the mother’s head just as young deer mice are under similar circumstances.

BEHAVIOR

The inherent or unconditioned behavior of these squirrels is interesting and can be usefully compared with the learned or conditioned responses that are in time built up by contact of squirrels with the park visitors. Young squirrels are quite timid upon emergence and for a few days depend upon the early morning hours for their initial foraging, a time when few people are around. They stay near a burrow entrance and hole up promptly if disturbed. This timidity is typical of the behavior of all squirrels in regions where contact with man is a rare incident. The air of easy assurance adopted by older park squirrels is evidence of their domesticability.

“. . . tail above his back about the angle a stove lifter projects from the lid . . .” |

These rodents have quite a tendency to dig in the ground and the young ones do a good deal of random digging before they actually tunnel a home site for themselves. In digging, the head is lowered and the fore limbs are moved very rapidly for a brief interval. The limbs are then held still while the head is raised for a look around. Digging and looking alternate at rapid intervals. If partly within a burrow a squirrel will back out to raise his head for observation. When well into a burrow, a squirrel, observed at the rim on July 15 1938, continued digging without kicking out the loose dirt which soon covered him. Hidden by this the squirrel continued on into the ground. About ten minutes later he burst out head first. The maneuver simultaneously cleared the burrow entrance and prepared it for possible retreat and got the squirrel clear of the entrance without embarrassing him with the adherence of loose earth. The interval had presumably been used to dig a length of burrow and a turn around.

Interesting comparisons can be made between the golden-mantled ground squirrel and a rather small brown gopher which occupies the same territory and is therefore a competitor. Both mammals dig a tunnel system, that of the gopher being attended to particularly during the winter so that “he, while his companion sleeps, is toiling upward in the night.” The squirrel feeds for the most part above ground while the gopher feeds for the most part underground on roots, there available, or on greens and grains pulled through the roof of the tunnel or gathered in short surreptitious forays launched from a tunnel entrance. In the latter the gopher emerges headfirst but goes to earth tail first. This reversal of direction without turning the body cannot be profitably employed by the squirrel for he ranges for a distance and maneuvers his body without regard to the position of the tunnel entrance. The squirrel always goes to earth head first. However, if a squirrel partly emerged is alarmed, he backs down gopher-like into the tunnel.

“. . . hungry little squirrels were adopted and fed by rim campground visitors.”

for awhile, may even register their annoyance by scolding the intruder as they hole up. But less blase, young squirrels, if not too greatly alarmed, immediately “pop up” after backing down, to see what is going on. This interesting example of youthful curiosity may be employed to demonstrate another pattern of the remarkable specificity of squirrel behavior. If in the game of pop up, back down, the young squirrel emerges enough to get one hind foot on the ground at the edge of the tunnel entrance he continues out, turns rapidly and goes to earth head first. This experiment, performed with a number of young squirrels, always produced the same result. The balance of advantages and disadvantages of the alternative methods reaches a critical point when one hind foot is in the air preparatory to complete emergence. Past this point, when the hind foot is on the surface of the earth, the advantage is presumably in favor of rapid emergence and immediate holing up.

“The air of easy assurance.” |

Squirrels can occasionally be seen carrying dry material which they presumably use for bedding. Grass from the previous fall which has been pressed down by the snow, dries rapidly when the snow has melted and so provides an acceptable bedding material. An individual squirrel, when not interfered with during the process, may make trip after trip to the same site of supply and carry a load of dry grass back to a tunnel each time. The route taken for the journey out may be repeated each time but a different route is usually chosen for the return journey and this is repeated on each return. An exception to this was provided by a squirrel in the utilities area which made twelve trips in carrying old bedding from one tunnel which it deposited in another. In this moving process the squirrel took the shortest route between the two tunnel entrances, which were only about thirty feet apart, and the routes going and coming were therefore coincident.

A squirrel gathering bedding works vigorously with forepaws and teeth to loosen grass which is taken between the jaws. The squirrel then stands up and trims this load into a neat bundle. More grass may be added and the trimming process repeated. Thus to arrange the load between the jaws a squirrel makes rapid and complicated movements with the forepaws. As a result he can run with his grass sheaf without stepping on loose ends and as the bundle does not project laterally much further than the ears the squirrel can enter a tunnel entrance on the run without embarrassment. A squirrel running with bedding has been seen to stop, stand up and retrim his load when a loose end of dried grass became detached and started to drag. On one occasion a squirrel running down the inner wall of the Sinnott Memorial ramp, stopped at the lower turn where two visitors offered him peanuts. To accept these the squirrel was obliged to put down his sheaf of grass and by running down the ramp the writer was able to prevent the squirrel from retrieving the grass before he ran away. This grass sheaf was in the form of an 8 which the squirrel had been holding in the center so a loop projected on each side. The grass in this bundle held together and could be lifted by the center or either loop without becoming disentangled.

Like most rodents the golden-mantled ground squirrel grooms himself around the head, neck, and belly with his fore paws. Hinder parts except the tail, are worked over with the teeth. The tail is combed by a sort of shucking motion with the fore paws and combed with the teeth as well. Grooming is particularly important in small mammals since a smooth coat conserves heat which radiates rapidly from the relatively large surface of a small creature. Squirrels dust themselves by a moderate rolling in dust piles often raised by a few rapid paw strokes for the purpose. They frequently save time by diving into dust like a base-runner making a head-first second. Frequently after the dive they lie spread-eagled in the dust for a brief period and this same position, with all limbs extended, may be used in resting. A well nourished little squirrel thus stretched out, after an interval of peanut gathering, has all the air of smugness carried by a lucky investor after a hard hour of coupon clipping.

“. . . edible objects are always lifted first by the jaws and then transferred to the forepaws . . .” |

Squirrels forage busily and nose over the ground for food. They frequently forage by standing on the hind limbs while they reach out and pull vegetation to the mouth with the fore paws. In this manner they nibble young leaves and flower buds of Newberry’s knotweed and bleeding-heart and the seeds of wild grasses, the heads of which they obtain by arm over arm reeling in of the stem. It is interesting that in spite of this use of the fore limbs in a special circumstance, that edible objects like peanuts are always lifted first by the jaws and then transferred to the fore paws for manipulation during husking or fragmentation prior to storage in the cheek pouches. Occasionally a squirrel with its mouth full of food will clutch an object on the ground and pull it toward the body but will then merely hold it with its paw until the mouth can be used as the grasping organ.

The golden-mantled ground squirrel has a vocabulary of at least four different sounds. There is a high- pitched “peesk” which is quite bird-like in tone, sometimes followed by a trill which is rather more musical than the similar trill of the western chipping sparrow. Both single and multiple noses seem prompted by excitement or alarm. These sounds are made while sitting, sometimes with one foot raised. The mouth is widely opened for the first sound and the body vibrates obviously with the trill. On August 6, 1938, the writer stopped to investigate a singing squirrel which had gathered an audience of a number of campers. One of them estimated that the squirrel, presumably a female since it was occasionally followed by young, had already sung for an hour and “sang almost every day!” There is a throaty little growl which is uttered as a warning to interlopers and during pursuit of them or while in the throes of combat. This sound is commonly employed when squirrels are competing for peanuts. Rather rarely a squirrel running from a pursuer, utters a series of high squealing notes when pursuit is close. In general these animals are rather silent and are usually credited with the single note first mentioned (Bailey, 193, p. 140).

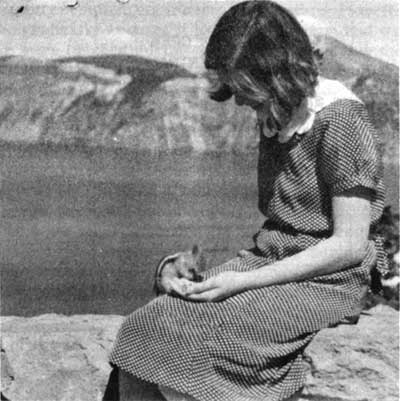

“It takes young squirrels a little while to accustom themselves to eating from visitors’ hands.” |

It takes young squirrels a little while to accustom themselves to eating from visitor’s hands. No critical test of this has been made, but by using experience at Government Headquarters as a criterion, it can be said that some young squirrels accept food the second or third day it is offered. Conditioning appears to be continuous over a long period for the biggest end presumably oldest individuals usually show the least hesitation. Even when young squirrels are taking food readily from the hand the bristling of the hairs on the tail show that the situation is producing considerable emotional disturbance. Emotionality in animals is difficult to estimate and this pilomotor response might be used in behavior experiments.

The greatest accumulation of squirrels in Crater Lake National Park is at the head of the Crater Wall Trail, immediately north of the Rim Parking Area. A dozen squirrels may often be seen here, begging, feeding, bickering with one another, or running home with the take. On August 8, 1938, a squirrel with full pouches was followed to its burrow which proved to be 220 yards west of the Crater Wall Trail on the edge of the fill for the shoulder of the Rim Road. The squirrel, which had been observed taking this route before, crossed the road twice to get to its burrow; once to the island at the Y just at the top of the hill and then across the south fork of the highway that leads to the Rim Road.

After considerable observation of known individual squirrels, the writer came to the conclusion that the squirrels with home sites a considerable distance from the head of the Crater Wall Trail filled their cheeks with more peanuts, before starting on the home trip, than did the squirrels with a shorter distance to go. The assumption that rodents acted as though they were conversant with the axiom, that you must have a paying load for a long haul, greatly interested park visitors although some said they would like to believe it but just couldn’t. Dr. Kenneth Gordan of Oregon State College, basing his observation on marked squirrels seen daily, came independently to this same conclusion: the squirrel with the longer route home takes the bigger load.

“. . . filled their cheeks with more peanuts . . .” |

Young of the year or yearling squirrels early in the season, not infrequently dig a small hole, after they have gone a short distance from a feeding area, and put their peanuts into it. The hole is then carefully covered with earth pushed into it and the site may be camouflaged by loose dirt dusted over it with brushing motions of the forepaws. Older squirrels dig these caches much more infrequently presumably because they have well established the routine of taking their food home. Late in the season of 1938 a squirrel was observed digging such a hole in the level ground just east of the Community House. This individual deposited some peanuts and had almost completed the earth cover when it was interrupted by the advent of another squirrel which started a territorial squabble. The two animals engaged in a running fight which took them as far as the west end of the Community House and must have occupied fifteen or twenty seconds. To the astonishment of the writer, one of the two, and presumably the one which had been engaged in covering its little hoard, returned to the site and completed the covering process including the refinement of brushing loose dirt over the site.

Not the least educative of these rodents’ reactions is the series of maneuvers gone through by a timid squirrel upon being offered food in hand, since this traces, in physical outline, the mental shuttling which is so often a prelude to making up one’s mind. Happy approach may take place until proximity to the large food- bearing animal lays on the paralysing hand of fear. Approach is checked and turned into precipitous flight. At a safer distance the possibility of food-getting again becomes the commanding stimulus and the squirrel will return and this time accept the proffered material. As soon as food is being taken into the mouth a squirrel is much “tamer” and may often be lifted by the fore paws as soon as it has placed these on the donor’s hand to obtain support while reaching for the food with its mouth. Squirrels will frequently sit contentedly on an outstretched hand or even climb about on visitors who remain still but are not patient with attempts at petting and they will struggle and bite vigorously if they are seized by the body or tail.

“Squirrels will frequently sit contentedly on an outstretched hand . . .”

DOMESTICATION

A certain number are captured and kept successfully as pets, often living for several years according to the testimony of Park visitors who have kept them. This is presumably due to their being able to thrive on the diet usual for the commoner domestic pets and to stand overfeeding. They hibernate in captivity even in the relatively warm Willamette Valley. During the winter of 1937-38 Professor Milne, of Oregon State College, kept two female squirrels in a nest box in his yard at Corvallis. Both squirrels hibernated, “rolled in a ball” with their heads between their fore limbs. They were cold to the touch and promptly resumed the hibernating posture if forcibly unrolled. They could be gradually aroused if put out in the sun and would attempt to bite if they were touched during this interval. During the warmth of the day they would remain active but would resume hibernation again that night and remain asleep unless again disturbed. Quite contrary to what is usually assumed, the smaller, thinner squirrel remained in hibernation two or three weeks after her bigger sister had emerged. Neither squirrel appeared to have lost weight during the hibernating period. Squirrels emerging from winter quarters at Crater Lake in 1937 and 1938 were all in good condition also.

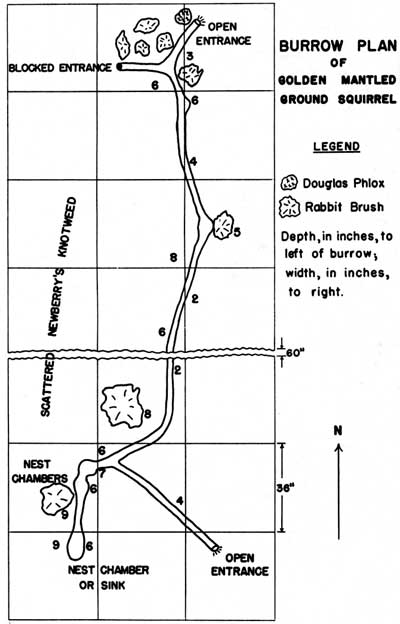

Three burrows were dug out in August 1937 to study the plan of construction. Two were empty (abandoned?) and one, herewith reproduced, contained a squirrel. He hung around awhile during the excavating process and regarded the operation with some concern.

The burrow which has been reproduced was the shortest and simplest of the three, being rather less than thirty feet in length. The longest tunnel was more than a hundred feet in total length, tortuous and containing cross connections. The third burrow was forty feet in length. Tunnels were usually about six inches below the surface, the greatest depth being reached in a cul-de-sac ten inches deep, either a nest chamber or sink. No tunnel contained nesting material. Diameters varied from two to four inches. Turn-arounds and nesting sites or sinks were from five to seven inches in diameter. All tunnels contained more than one open entrance, with one or more blocked with earth.

Tunnels went under rocks and the roots of bushes when these were encountered but entrances were not necessarily hidden. In general one might say that the tunnels were like the squirrel, rather simple and direct.

LITERATURE

Bailey, Vernon. 1936. Mammals and Life Zones of Oregon. North American Fauna No. 55. U.S.D.A. Bureau of Biological Survey.

Gordon, K. 1943. The Natural History and Behavior of the Western Chipmunk and Mantled Ground Squirrel, Oregon State Monograph Studies in Zoology No. 5.

Grinnell, J. and T. I. Storer. 1924. Animal Life in the Yosemite, California University Museum Vertebrate Zoology Contribution, California University Publications of Zoology.

Other pages in this section