“Comedy is supplied by the air of brisk alertness . . .” |

Golden-mantled ground squirrels are said by Vernon Bailey to have but one brood a year of four to six or more young. Grinnell found an average of five young in five females in Yosemite National Park. The number probably increases with the age of the mother and as fully adult females have ten functional mammae they could easily accommodate larger broods. In 1936 a mother squirrel was observed moving nine little ones from a burrow in the rim campground and in 1938 the accidental death of a mother squirrel was followed by the exit of eight hungry little squirrels which were adopted and fed by rim campground visitors. Young are reported by Vernon Bailey to be born late in June or early in July. This checks with observations at Crater Lake National Park where in both 1937 and 1938 young squirrels emerged from burrows along the rim during the first week in August. The adopted brood mentioned in the previous paragraph seemed to be about three weeks old on August the eighth. A small newly-emerged squirrel was seen coming out of a burrow in the rim campground as late as September 3, 1937.

“. . . searching industriously for peanuts . . .” |

The episode mentioned above in which a mother squirrel moved young from a burrow, part of which had been collapsed by a car, shows that these animals share the typical mammalian habit of moving young to less menaced positions. In August 1938 Dr. Fred Miller, park physician, observed the moving of six young from a nest somewhere in the Community House through the door to a refuge somewhere outside the building. The young were carried by the body with ventral surface toward the mother’s mouth and curled around the mother’s head just as young deer mice are under similar circumstances.

BEHAVIOR

The inherent or unconditioned behavior of these squirrels is interesting and can be usefully compared with the learned or conditioned responses that are in time built up by contact of squirrels with the park visitors. Young squirrels are quite timid upon emergence and for a few days depend upon the early morning hours for their initial foraging, a time when few people are around. They stay near a burrow entrance and hole up promptly if disturbed. This timidity is typical of the behavior of all squirrels in regions where contact with man is a rare incident. The air of easy assurance adopted by older park squirrels is evidence of their domesticability.

“. . . tail above his back about the angle a stove lifter projects from the lid . . .” |

These rodents have quite a tendency to dig in the ground and the young ones do a good deal of random digging before they actually tunnel a home site for themselves. In digging, the head is lowered and the fore limbs are moved very rapidly for a brief interval. The limbs are then held still while the head is raised for a look around. Digging and looking alternate at rapid intervals. If partly within a burrow a squirrel will back out to raise his head for observation. When well into a burrow, a squirrel, observed at the rim on July 15 1938, continued digging without kicking out the loose dirt which soon covered him. Hidden by this the squirrel continued on into the ground. About ten minutes later he burst out head first. The maneuver simultaneously cleared the burrow entrance and prepared it for possible retreat and got the squirrel clear of the entrance without embarrassing him with the adherence of loose earth. The interval had presumably been used to dig a length of burrow and a turn around.

Interesting comparisons can be made between the golden-mantled ground squirrel and a rather small brown gopher which occupies the same territory and is therefore a competitor. Both mammals dig a tunnel system, that of the gopher being attended to particularly during the winter so that “he, while his companion sleeps, is toiling upward in the night.” The squirrel feeds for the most part above ground while the gopher feeds for the most part underground on roots, there available, or on greens and grains pulled through the roof of the tunnel or gathered in short surreptitious forays launched from a tunnel entrance. In the latter the gopher emerges headfirst but goes to earth tail first. This reversal of direction without turning the body cannot be profitably employed by the squirrel for he ranges for a distance and maneuvers his body without regard to the position of the tunnel entrance. The squirrel always goes to earth head first. However, if a squirrel partly emerged is alarmed, he backs down gopher-like into the tunnel.

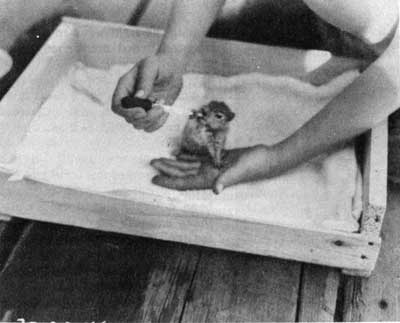

“. . . hungry little squirrels were adopted and fed by rim campground visitors.”

for awhile, may even register their annoyance by scolding the intruder as they hole up. But less blase, young squirrels, if not too greatly alarmed, immediately “pop up” after backing down, to see what is going on. This interesting example of youthful curiosity may be employed to demonstrate another pattern of the remarkable specificity of squirrel behavior. If in the game of pop up, back down, the young squirrel emerges enough to get one hind foot on the ground at the edge of the tunnel entrance he continues out, turns rapidly and goes to earth head first. This experiment, performed with a number of young squirrels, always produced the same result. The balance of advantages and disadvantages of the alternative methods reaches a critical point when one hind foot is in the air preparatory to complete emergence. Past this point, when the hind foot is on the surface of the earth, the advantage is presumably in favor of rapid emergence and immediate holing up.

“The air of easy assurance.” |

Squirrels can occasionally be seen carrying dry material which they presumably use for bedding. Grass from the previous fall which has been pressed down by the snow, dries rapidly when the snow has melted and so provides an acceptable bedding material. An individual squirrel, when not interfered with during the process, may make trip after trip to the same site of supply and carry a load of dry grass back to a tunnel each time. The route taken for the journey out may be repeated each time but a different route is usually chosen for the return journey and this is repeated on each return. An exception to this was provided by a squirrel in the utilities area which made twelve trips in carrying old bedding from one tunnel which it deposited in another. In this moving process the squirrel took the shortest route between the two tunnel entrances, which were only about thirty feet apart, and the routes going and coming were therefore coincident.