The greatest accumulation of squirrels in Crater Lake National Park is at the head of the Crater Wall Trail, immediately north of the Rim Parking Area. A dozen squirrels may often be seen here, begging, feeding, bickering with one another, or running home with the take. On August 8, 1938, a squirrel with full pouches was followed to its burrow which proved to be 220 yards west of the Crater Wall Trail on the edge of the fill for the shoulder of the Rim Road. The squirrel, which had been observed taking this route before, crossed the road twice to get to its burrow; once to the island at the Y just at the top of the hill and then across the south fork of the highway that leads to the Rim Road.

After considerable observation of known individual squirrels, the writer came to the conclusion that the squirrels with home sites a considerable distance from the head of the Crater Wall Trail filled their cheeks with more peanuts, before starting on the home trip, than did the squirrels with a shorter distance to go. The assumption that rodents acted as though they were conversant with the axiom, that you must have a paying load for a long haul, greatly interested park visitors although some said they would like to believe it but just couldn’t. Dr. Kenneth Gordan of Oregon State College, basing his observation on marked squirrels seen daily, came independently to this same conclusion: the squirrel with the longer route home takes the bigger load.

“. . . filled their cheeks with more peanuts . . .” |

Young of the year or yearling squirrels early in the season, not infrequently dig a small hole, after they have gone a short distance from a feeding area, and put their peanuts into it. The hole is then carefully covered with earth pushed into it and the site may be camouflaged by loose dirt dusted over it with brushing motions of the forepaws. Older squirrels dig these caches much more infrequently presumably because they have well established the routine of taking their food home. Late in the season of 1938 a squirrel was observed digging such a hole in the level ground just east of the Community House. This individual deposited some peanuts and had almost completed the earth cover when it was interrupted by the advent of another squirrel which started a territorial squabble. The two animals engaged in a running fight which took them as far as the west end of the Community House and must have occupied fifteen or twenty seconds. To the astonishment of the writer, one of the two, and presumably the one which had been engaged in covering its little hoard, returned to the site and completed the covering process including the refinement of brushing loose dirt over the site.

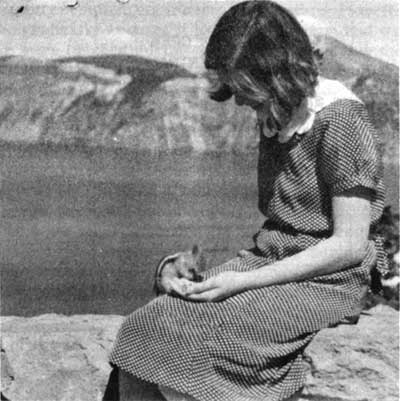

Not the least educative of these rodents’ reactions is the series of maneuvers gone through by a timid squirrel upon being offered food in hand, since this traces, in physical outline, the mental shuttling which is so often a prelude to making up one’s mind. Happy approach may take place until proximity to the large food- bearing animal lays on the paralysing hand of fear. Approach is checked and turned into precipitous flight. At a safer distance the possibility of food-getting again becomes the commanding stimulus and the squirrel will return and this time accept the proffered material. As soon as food is being taken into the mouth a squirrel is much “tamer” and may often be lifted by the fore paws as soon as it has placed these on the donor’s hand to obtain support while reaching for the food with its mouth. Squirrels will frequently sit contentedly on an outstretched hand or even climb about on visitors who remain still but are not patient with attempts at petting and they will struggle and bite vigorously if they are seized by the body or tail.

“Squirrels will frequently sit contentedly on an outstretched hand . . .”

DOMESTICATION

A certain number are captured and kept successfully as pets, often living for several years according to the testimony of Park visitors who have kept them. This is presumably due to their being able to thrive on the diet usual for the commoner domestic pets and to stand overfeeding. They hibernate in captivity even in the relatively warm Willamette Valley. During the winter of 1937-38 Professor Milne, of Oregon State College, kept two female squirrels in a nest box in his yard at Corvallis. Both squirrels hibernated, “rolled in a ball” with their heads between their fore limbs. They were cold to the touch and promptly resumed the hibernating posture if forcibly unrolled. They could be gradually aroused if put out in the sun and would attempt to bite if they were touched during this interval. During the warmth of the day they would remain active but would resume hibernation again that night and remain asleep unless again disturbed. Quite contrary to what is usually assumed, the smaller, thinner squirrel remained in hibernation two or three weeks after her bigger sister had emerged. Neither squirrel appeared to have lost weight during the hibernating period. Squirrels emerging from winter quarters at Crater Lake in 1937 and 1938 were all in good condition also.

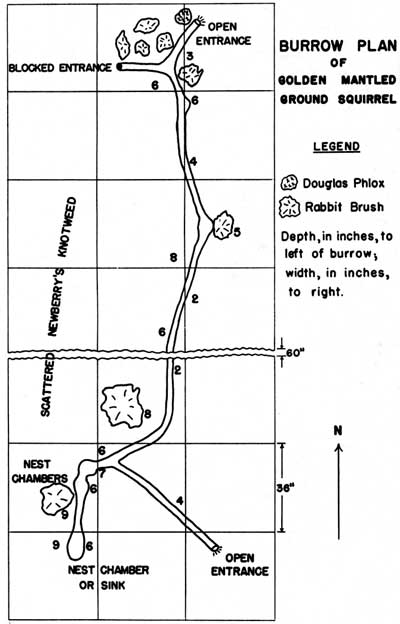

Three burrows were dug out in August 1937 to study the plan of construction. Two were empty (abandoned?) and one, herewith reproduced, contained a squirrel. He hung around awhile during the excavating process and regarded the operation with some concern.

The burrow which has been reproduced was the shortest and simplest of the three, being rather less than thirty feet in length. The longest tunnel was more than a hundred feet in total length, tortuous and containing cross connections. The third burrow was forty feet in length. Tunnels were usually about six inches below the surface, the greatest depth being reached in a cul-de-sac ten inches deep, either a nest chamber or sink. No tunnel contained nesting material. Diameters varied from two to four inches. Turn-arounds and nesting sites or sinks were from five to seven inches in diameter. All tunnels contained more than one open entrance, with one or more blocked with earth.

Tunnels went under rocks and the roots of bushes when these were encountered but entrances were not necessarily hidden. In general one might say that the tunnels were like the squirrel, rather simple and direct.

LITERATURE

Bailey, Vernon. 1936. Mammals and Life Zones of Oregon. North American Fauna No. 55. U.S.D.A. Bureau of Biological Survey.

Gordon, K. 1943. The Natural History and Behavior of the Western Chipmunk and Mantled Ground Squirrel, Oregon State Monograph Studies in Zoology No. 5.

Grinnell, J. and T. I. Storer. 1924. Animal Life in the Yosemite, California University Museum Vertebrate Zoology Contribution, California University Publications of Zoology.

***previous*** — ***next***