Crater Lake Fishing, 1952

During most seasons many of those who visit Crater Lake National Park go down the trail to the lake. Usually quite a number of these people try their hand at fishing, either from boats or from the shores. Hasler and Farner (1942) report that 1270 anglers who fished from boats on Crater Lake in 1937 took 1302 fish — an average of a little more than one fish per angler for the season, which included the months of July and August. The same authors made similar reports for the seasons of 1938 through 1940. In 1940 their observations show that 837 anglers caught 4188 fish, or an average of about 5 fish per fisherman. In addition to these records, the creel census report for 1950 (Crater Lake National Park files, no author) states that in July and August of that year, 229 anglers averaged 1.12 fish per person. Since it is obviously very difficult to obtain records of shore fishing, none of the above figures include such data.

From the standpoint of the fisherman — to say nothing of those who just wanted to view the lake from the shore, or to ride upon its surface — the 1952 season was a great disappointment. Excessive snows of the previous winter, coupled with a late spring, made it evident very early that the lake trail would not be opened by the beginning of the season. A more thorough investigation indicated August 1 to be the probable earliest date that the 1.6 miles of trail could be made passable. That meant, of course, that July, the best fishing month (Hasler and Farner, 1942) would pass with the lake inaccessible to visitors.

According to plan, therefore, a crew began to clear snow and repair damaged portions of the trail. The work, in spite of great difficulties, progressed about on schedule. Then, with completion anticipated to be only one or two days away, the final blow fell. Several daily rains had loosened the soft material along the face of the wall, and a particularly heavy storm released an avalanche of many tons of rocks, debris, and water which rushed down the slopes and washed out completely the lower part of the trail. This made necessary so much new permanent construction that the lake remained closed to visitors for the entire season.

Although Crater Lake is by no means a fishing resort, it is of scientific interest to make yearly observations of the fish and of conditions which affect their existence there. Along this line there was planned for 1952 an extensive investigation of limnological conditions and of life in the lake in order that more might be known of the fish population. It was hoped, also, to be able to learn something of how large a fish population the lake might support. Difficulty of reaching the lake, however, greatly hampered such operations. Very few data, therefore, have been collected.

The first trip of the year to the lake — and to Wizard Island — was made by the author on July 13 in company with Paul Herron, who was to have operated the launches for the Crater Lake National Park Company, and Wallace Ernst, one of the other ranger naturalists. Since the trail at this time still was almost completely covered with snow, descent was made along one of the ridges where trees were of great assistance in maintaining footholds. Despite this, however, much of the way was over snowbanks with travel on “all- fours.” At the lake shore a row boat had been secured high in a tree the previous fall to protect it from snow damage. This was lowered and placed in the water for the trip to Wizard Island.

Before heading across the lake, we rowed around to a point where Joseph Diller, who made the first extensive geological studies of Crater Lake, was supposed to have placed a bronze tablet on a rock face. The tablet has apparently been gone for some years but the imprint remains clearly marked. If the information is correct that the bottom of the tablet was at water level at that time, 1873, the present water level is an estimated six feet below that point. According to Paul Herron, however, the water appeared to be considerably higher than last season. At Wizard Island, also, evidence of the higher water was observed. One of the government boathouses, constructed in 1942 with its lower sill eighteen inches above water level, is now so nearly submerged that the gunwale of the rowboat would just slip under its eaves. Later in the season — August 19 — the water level was measured by Paul Herron and the author. It was found to be 11 feet 1 inch below the October 1, 1942 level. Also, it was estimated from pollen deposits, that the water was about three inches lower than on July 13 of this year.

In 1952, surface temperature readings, taken with a standard laboratory thermometer, were obtained from shore on August 3, 7, and 17. These were, respectively, 17.3° C. (63.14° F.), 16.8° C. (62.24° F.), and 16.9° C. (62.42° F.). The first and last of these were taken below the Wineglass, and the other near the foot of the government trail. At this writing, only one open-water surface temperature reading had been taken. This was between government trail and Wizard Island on August 7 and was 16.3° C. (61.34° F.). Thus, temperatures this season appear to be nearly the same as maximum for 1937.

Although only official personnel were permitted access to the lake, there was some fishing this season by local residents who managed to get down to the lake. Fortunately, a few of these records were obtained. Seasonal Ranger Bob Morris contacted one group of anglers who had taken 31 fish — 30 Rainbow trout (Salmo gairdnerii irideus) and one Sockeye salmon (Oncorhyncus nerka kennerlyi) — on July 27. These were caught with dry flies cast from shore. The trout ranged from ten to sixteen inches in length, and the salmon was ten inches long. No viscera were obtained but the fishermen said that some of the Rainbows were spawning, while others had already completed this function.

The following week, Ranger Morris also contacted a group of three anglers who had caught seven Rainbows with similar tackle. Records of four other Rainbow trout and two salmon were obtained by the author. The trout were from nine to slightly over thirteen inches in length, and the salmon between eight and nine inches. This total of 42 fish undoubtedly does not include all those taken but it is an interesting comparison with the figures cited in the introductory paragraph.

At the date of this writing, three — two Rainbow trout and one Sockeye salmon — of four fish stomachs collected had been examined to study food habits. The trout had been caught from shore, and the salmon was taken on a troll line from Skell Channel. It is of interest to observe that availability of a food item would appear to be the important factor in its selection by the fish. These fish were taken at the time of the California Tortoise Shell butterfly emergence when great numbers of these insects were flying over the lake. Many of them could be seen floating on the water where they had probably fallen exhausted. The stomachs of the salmon and one trout contained, respectively, nine and six of these butterflies.

One further item of some note was the finding of a single specimen of a copepod,Cyclops serrulatus, in the stomach of the salmon. This, in itself, would not seem important since microcrustaceans of the copepod group usually are found in most lakes and ponds. In looking through the available literature on previous studies of Crater Lake, no reference to this particular group of animals could be located, although their near relative, Daphnia (the water flea), was mentioned by several authors. It is not known, therefore, if copepods were not in the lake when the other investigations were made, or if they were overlooked. Microcrustacea are important food items, particularly for small fish, and sometimes compose a portion of the diet of larger fish. Consequently, it is gratifying to note their occurrence here.

The foregoing is a very meager gleaning as compared with many previous seasons. The only indication of fish abundance seen this year was the observance of considerable surfacing by the fish one day in late July. This does, however, give some indication of present conditions in Crater Lake.

References

Hasler, Arthur D. 1938. Fish biology and limnology of Crater Lake, Oregon. Journal of Wildlife Management, 2(3):94-103.

Hasler, Arthur D. and D. S. Farner. 1942. Fisheries investigations in Crater Lake, 1937-1940. Journal of Wildlife Management, 6(4): 319-327.

Kemmerer, George, J. F. Bovard, and W. T. Boorman. 1923-1924. Northwestern lakes of the United States: biological and chemical studies with reference to possibilities in production of fish. Bulletin of the Bureau of Fisheries, 39:51-140.

A New Horned Toad Record for Crater Lake National Park

Although horned-toads are quite common in suitable habitats at lower elevations around Crater Lake National Park and at isolated localities in the Cascade Mountains (Gordon, 1939:68), they are obviously rare within the Park. Prior to this season there have been only two records for the Park (Farner and Kezer, M.S. 1951).

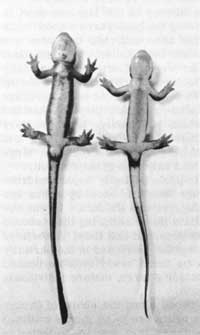

Pigmy Horned Toad. Photograph of a preserved specimen. |

Campbell (1934:2) states that he saw a specimen “which had been caught by the CCC boys of the Wineglass Camp in the woods several miles down the Motorway which leaves Wineglass and goes toward the North boundary.” This locality is in good horned-toad habitat. Unfortunately this specimen was not preserved. Joseph S. Dixon obtained a specimen (MVZ 40761) collected by James Tucker “on August 15, 1944, at 6000 feet on pumice desert 5 miles north of Crater Lake about half way between Grouse Hill and Timber Crater.” We have searched this area for this lizard numerous times without success. One must not exclude the possibility that the specimen obtained by Dixon had escaped or was released by a visitor since the collecting locality is near a highway and since these little reptiles are frequently acquired and kept as pets.

On 26 June 1952 Park Naturalist Harry C. Parker and Assistant Park Naturalist Donald S. Farner collected a specimen (CLNP 523) along the Rim of Wheeler Creek Canyon at 5550 feet. Although this specimen was taken near the East Entrance Highway it can nevertheless be safely regarded as a legitimate record for the Park since the highway had not yet been opened to public travel for the season.

The horned-toads of Crater Lake National Park and vicinity are referred to Phrynosoma douglassii douglassii (Bell), the Pigmy Horned Toad (Farner and Kezer, M.S. 1951).

References

Campbell, Berry. 1934. Annotated list of the vertebrates of Crater Lake. Mimeographed, 22 pp.

Dixon, Joseph F. 1936-1945. Unpublished field notes recorded in Crater Lake National Park now in the files of the National Park Service, Region Four Office, San Francisco.

Farner, Donald S. and Kezer, James. 1951. Notes on the amphibians and reptiles of Crater Lake National Park. To appear in The American Midland Naturalist in 1953.

Gordon, Kenneth. 1939. The amphibia and reptilia of Oregon. Oregon State Monographs, Studies in Zoology, No. 3. 82 pp.

The 1952 Invasion of California Tortoise Shell Butterflies

At irregular intervals Crater Lake National Park is visited by huge numbers of Tortoise Shell Butterflies, Aglais californica Bdv. Previous invasions have been described by Scullen (1930), Constance (1931), and Lowrie (1951). Doubtless others have occurred without being recorded. The chronology of the 1952 invasion was very similar to that of 1951. The butterflies first began to appear about July 30 and seemed to reach their maximum abundance during the first week in August when prodigious numbers were to be observed in flight and resting on buildings. They were observed in abundance at the summits of Mt. Scott, the Watchman, and Dutton Cliff.

Doubtless these butterflies constitute an abundant source of food for several species of animals. During the last week of July and the first week of August there was a pronounced increase in the numbers of Clark’s Nutcrackers, Nucifraga columbiana(Wilson), along the Rim Highway. On several occasions I have noted them feeding on the California Tortoise Shells which had been killed by automobiles. The same observation has been made by Ranger-Naturalist R. M. Brown. On August 10, Ranger Naturalist C. Warren Fairbanks saw three ravens, Corvus corax Linnaeus, feeding on these butterflies on the highway near Llao Rock. He also found six in the stomach of a Rainbow Trout, Salmo gairdnerii Richardson, caught near Eagle Cove on August 17. Ranger-Naturalist Brown also observed a Golden-Mantled Ground Squirrel, Citteilus lateralis (Say), taking one on August 7 near Hillman Peak. These ground squirrels were frequently observed to take butterflies which dropped from the radiators of automobiles at the checking stations. The use of butterflies as food by the Golden-Mantled Ground Squirrel, however, is apparently not unusual (Gordon 1943:27).

References

Constance, L. 1931. A butterfly pilgrimage. Nature Notes from Crater Lake, 4(2):3-4.

Gordon, Kenneth. 1943. The natural history and behavior of the Western Chipmunk and the Mantled Ground Squirrel. Oregon State Monographs, Studies in Zoology, No. 5. 104 pp.

Lowrie, Donald C. 1951. Butterflies of Crater Lake National Park. Crater Lake Nature Notes, 17:10-11.

Scullen, H. A. 1930. The California Tortoise Shell Butterfly. Nature Notes from Crater Lake, 3(3):2.

The Mazama Newt: A Unique Salamander of Crater Lake

Under-surfaces of two closely related newts. A Mazama newt from Crater Lake at the left and a common Oregon newt on the right. |

During the past two seasons many of the visitors to Crater Lake National Park have been able to get some first hand contact with one of the most distinctive and interesting animals of the Lake. This is a salamander or water-dog, oftentimes called the Mazama newt or Crater Lake newt; it is found no place in the world outside of the waters of Crater Lake. Believing that many of the visitors to the Park would be interested in this unusual animal, we have frequently exhibited living specimens during lectures in the lodge and the community building and the excitement that is invariably caused by the circulation of the jars of newts has indicated to us that these salamanders are indeed a real source of interest to our visitors. If one compares the Mazama newt (Triturus granulosus mazamae) with the common Oregon newt (Triturus granulosus granulosus) it is clearly evident that the two are very closely related. Indeed, the difference between the two is simply a matter of the pigmentation of the lower surface; the immaculate orange-yellow of the Oregon newt is replaced in the Mazama newt with varying amounts of dark pigment that appears to invade the under surface of the animal from the sides. This difference in pigmentation is illustrated in the photograph in which the under surfaces of the two kinds of newts are shown. It should be pointed out that the amount of black pigment on the lower surface of a Mazama newt is highly variable; some individuals have lots of it and others approach closely the pigmentation of the common Oregon newt.

Our best interpretation of the Crater Lake newt population assumes that hundreds of years ago some common Oregon newts were able to get into the Lake through an unknown route, probably during a period when the climate was much wetter. The steep, dry walls of the Lake Rim have apparently served as an isolating mechanism, allowing the Crater Lake newts to develop a different genetic composition and resulting in the pigmentation differences that now separate this group of water-dogs from the common Oregon newt. It is a very interesting fact that a specimen of the common Oregon newt collected within the Park boundaries as close as two and one-half miles from the Lake showed none of the under-surface black of a Mazama newt. This is surely a tribute to the isolating function of the caldera walls.

Our present knowledge of the life history of the Mazama newt is fragmentary, despite the fact that during the past years a good many members of the ranger-naturalist staff have searched the water and the shoreline of Crater Lake for such information. The smallest larvae that we have found in the Lake were collected in a partially cut-off pool behind the Government Boathouse on Wizard Island during the first week of September, 1951. Ten of these larvae had an average length of about 3/4 inch which indicated to us that they had hatched from the egg mass at least three weeks previously. It seems very probable that the eggs from which these larvae came had been laid during the summer, perhaps back in the spaces between the large blocks of lava where they would be found only with great difficulty.

In the water along the shore and in pools partially separated from the Lake, large larvae with an average length of about 3-1/4 inches are commonly found. Our limited data suggest that the small larvae observed in the pool on Wizard Island attain this size during their second season of growth, undergoing metamorphosis at that time. Associated with the large larvae in the water along the shore and in the partially cut-off pools on Wizard Island, may be found newly metamorphosed newts and adults of various sizes, including large, mature individuals averaging about 6-3/4 inches in total length.

If one lifts up the rocks and driftwood along the shore of Crater Lake he soon learns that the Mazama newts are by no means confined to the actual water of the Lake. Oftentimes they may be collected in large numbers under the debris along the shore, frequently in association with the long-toed salamander, Ambystoma macrodactylum. In this non-aquatic environment they appear desiccated and sluggish with extremely granular skins. We have considered the possibility that these semi-terrestrial individuals represent a definite stage in the life history of this newt; however, since no single age group is involved, it seems more probable that a transitory semi-terrestrial existence represents an aspect of the behavior of the Mazama newt at various times during its life.

On several different occasions we have observed large aggregations of the Mazama newt along the shore of the Lake. Usually these aggregations consist of semi-terrestrial individuals in groups of about twelve to fifteen out of the water and under rocks or pieces of driftwood. A somewhat different kind of aggregation was observed September 6, 1951, on the east side of Eagle Point where the shore of the Lake consists of a rocky beach covered with willows. Two hundred and fifty-nine newts were massed together in an area of water not more than thirty feet square, the vast majority of these being under a single flat rock about nine feet square, resting on other rocks in approximately one foot of water. Making up the aggregation were adults of varying sizes, large larvae and newly metamorphosed individuals.

On August 7, 1952, an enormous aggregation of Mazama newts was observed under rocks in the shallow water of about 15-20 feet of shoreline in Eagle Cove. We estimated that at least three hundred newts were involved in this aggregation and, as previously noted, all sizes from large larvae to the largest adults were present. At this time the significance of these aggregations is not understood.

From the zoological standpoint, the newts of Crater Lake are particularly interesting because they provide material for the determination of the time required for the genetical change that is necessary for the development of a subspecies. The collapse of Mt. Mazama has been accurately established by modern techniques as occurring between six and seven thousand years ago. This information clearly indicates that newts could not have entered the water of Crater Lake more than about six thousand years ago; moreover, considering the subsequent eruptions that brought about the formation of Wizard Island, it is highly probable that the Lake newt population was established much more recently. Indeed, the Mazama newts are doubtless one of the most clearly dated cases of subspeciation available any place in the world.

Snow Crater – Nature’s Calendar

Snow Crater is a unique and interesting feature of Crater Lake National Park. It is located in the summit of Scoria Cone in a remote section of the Park near the South Boundary. It may be reached by traveling about one and a half miles on the Red Blanket Motorway, and then about one and a half miles in a southeasterly direction. Regardless of the heat of the summer season, the snow that has fallen in this crater from the previous winter never entirely melts; thus over a period of years a sizable mass of snow has accumulated in the depression at the top of the cone. It is particularly interesting to note that a season’s accumulation of snow in the crater constitutes a distinct layer, clearly demarked from the younger layers above and the older layers below.

The layers or “varves” of snow remind one of the varves that are often deposited by lake waters and from which it is possible to learn much regarding the time and conditions during which the lake existed. Varves deposited by a lake consist of alternating layers of dark and light sediments. During the summer, the life in a pond or lake is on the increase because of good growing conditions, and likewise, is on the decline in late fall and winter. As winter approaches and organic matter dies, it settles and turns dark, thus creating a dark layer of sediment. During the colder months, the sediments laid down are of an inorganic nature and much lighter than the previous ones. Thus one layer of both dark and light constitutes the sediments laid down during a one- year period and gives rise to a single verve from which a geologist may read certain facts regarding the conditions prevailing in the lake during the deposition.

The accumulation of snow and debris in Snow Crater here in the Park is in many respects analogous to the formation of the varves of a lake. Each winter brings about an accumulation of snow. and then during the summer, a layer of rocks, dirt, and debris from the trees forms on top of the snow. In this manner there is developed a “snow verve,” representing one year of deposition.

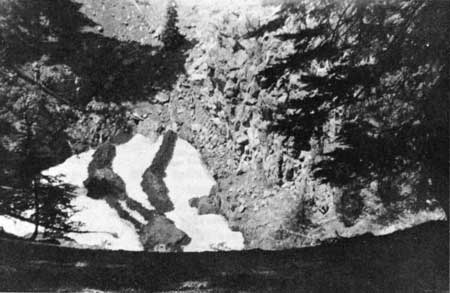

Looking into Snow Crater from the summit of Scoria Cone about fifty feet above the surface of the snow. The streaks are mud that has washed over the snow from heavy rains.

As far as I have been able to determine, Snow Crater has been visited only about four times since 1948. During 1948, Rangers William Kinsley, Richard Marquis, and a third person visited the Crater at least twice. On the second trip, an exploration was made in a crevice between the snow and the rock wall and, according to the report of Ranger Marquis, about 75 snow varves were counted, representing as many years of snow accumulation. In 1949 Ranger Kinsley and I visited Snow Crater but we were unable to make any further studies because of the unusually heavy snowfall of the preceding winter. During the summer of 1952 I was able to make a second trip to this remarkable crater. The accompanying photograph was taken at that time. The near record snowfall of the 1951-52 winter had hidden all of the possible exposures at which the snow varves might have been counted. It seems very possible that further exploration will be fruitless until perhaps mid-September, barring an early winter.

Snow Crater is one of the many out-of-the-way features of Crater Lake National Park rarely visited by any of the thousands of individuals who come to the Park each summer. I hope that this Nature Notes article will serve to call this interesting accumulation of snow to the attention of hikers and those who are interested in geology. I am sure that there are many Park visitors who will find a trip to Snow Crater a fascinating experience.

Other pages in this section