American Pintail on Crater Lake

A flight of Pintails as seen from Sinnott Memorial. Pen and ink sketch by Ranger-Naturalist Charles F. Yocom.

Although many ornithologists have investigated the bird life of Crater Lake National Park over a period of years, only one sight record for the American pintail (Anas acuta tzitzihoa) had been recorded until this season. Farner (1952) states that J. C. Wright, fireguard on Mount Scott, on August 22, 1949, observed a flock of 20 to 30 Pintails flying southward toward Upper Klamath Lake.

From July 28 to August 3, 1952, several hundred waterfowl were seen on Crater Lake or flying out over the rim of this lake by ranger naturalists. Apparently most of these ducks were Pintails, for all flocks seen by the writer at close range were this species. The following records indicate the large number of waterfowl that were seen:

| Date | Number | Location | Observer |

| AM 28 July | 100 | on surface near Phantom Ship | D.S. Farner |

| AM 30 July | 1 flock | on surface out from Sinnott Memorial | Robert Wood |

| AM 31 July | 2 flocks | near Rim Village flying south | Warren Fairbanks |

| AM 1 August* | 150 | near Wizard Island | C.F. Yocom |

| AM 1 August | large flock | east of Wizard Island | C.F. Yocom |

| AM 2 August | 60 | near Wizard Island | C.F. Yocom |

| PM 2 August* | 200-500 | feeding and flying near Garfield Peak | Yocom and Farner |

| PM 2 August | 300+ | feeding west of Phantom Ship | Yocom and Farner |

| AM 3 August* | 200 | flying near Sinnott Memorial | Robert Wood |

| AM 3 August | 200+ | on surface out from Sinnott Memorial | Robert Wood |

| PM 3 August | 3 flocks | far out in lake | C.F. Yocom |

| PM 3 August* | 800+ | beyond Wizard Island | D.S. Farner |

*These flocks were identified as Pintails. The large flock seen by Farner and the writer on August 2 flew very close and were seen under favorable light so that unmistakable markings were seen.

These flocks of Pintails were undoubtedly migrants that are known to pass through Washington and Oregon and arrive in California during the last of July and the first part of August. This early flight of Pintails is not understood by waterfowl biologists in the Pacific flyway, but banding will assist in unraveling this problem. There are many later flights of Pintails as indicated by Yocom (1951). As a matter of fact the writer has seen migrating Pintails 465 nautical miles west of Cape Blanco, Oregon, on August 30, 1945.

It is not unusual that Pintails should pass over Crater Lake National Park in migrating, but it is unusual that large flocks alighted on the lake and remained for some time, as Pintails are pond ducks which normally feed by means of tipping in shallow marshes and lakes. Flocks observed on Crater Lake appeared to be feeding. They remained in close-knit bunches and swam over the surface quite rapidly, often times flying a short distance, then milling about in compact groups. Evidently these birds were securing some desirable food items on the surface of the lake.

No large flocks of ducks were seen after August 3rd except a flock of over 100 individuals noted on the Lake east of Wizard Island on August 17, by D. S. Farner. The birds observed leaving the Lake flew out over the Rim between Sun Notch and The Watchman, going toward Klamath Lake and it is believed that all of the flocks seen between July 28 and August 3 passed on South.

References

Farner, Donald S. 1952. The Birds of Crater Lake National Park. University of Kansas Press. IX + 200 pp.

Yocom, Charles F. 1951. Waterfowl and Their Food Plants in Washington. University of Washington Press, Seattle, Washington. XVI + 272 pp.

Two Interesting Ornithological Observations

During the month of August we recorded two observations which are of considerable interest since they add materially to our knowledge of the avifauna of the Park. On August 23, 1952, a juvenile English Sparrow, Passer domesticus (Linnaeus), was seen near the Information Building at the Rim Village. Since this is considerably out of the altitudinal range and habitat of this species the possibility of this individual having been liberated in the vicinity should not be precluded.

Farner (1952: 167) includes this species in the supplemental list of birds of the Park on the basis of observations by Joseph Dixon in 1945 near the South Boundary.

On August 31, 1952 we saw two Band-tailed Pigeons, Columba fasciata (Say), perched in the dead top of a mountain hemlock at about 7400 feet on Dutton Ridge. This is a particularly significant record since this species was admitted to the Park list (Farner, 1952: 50) solely on the basis of the remains of a single bird found on July 24, 1945 by Joseph Dixon near the head of Castle Creek. This species must still be regarded as a rare straggler in Crater Lake National Park.

References

Dixon, Joseph. 1945. Field notes in the files of the Regional Office of the National Park Service, San Francisco

Farner, Donald S. 1952. The Birds of Crater Lake National Park, University of Kansas Press, Lawrence. ix + 200 pp.

Gray Diggers and Muskrats

An adult male Douglas ground squirrel, Citellus beecheyi douglasii Richardson, was found dead along the west entrance highway about four miles within the park boundary, on July 15, 1952. This animal, also known as the gray digger, was noticed by Art C. Toth, foreman of the fire guards, who brought it to Park Headquarters to be added to our mammal collection (CLNP # 522). Although these ground squirrels have been observed occasionally along the western and southern boundaries of the park, the only other collection was made in 1937 at the south entrance (Walks, 1947:53). Since the previous observations within the park have all been made near the west entrance (4800) feet and the south entrance (4400) feet, the finding of this mature individual, apparently killed by a car, at an elevation of about 5700 feet establishes a new record for Crater Lake National Park.

Gray Digger |

The gray digger lives principally in sagebrush areas of the Upper Sonoran Zone and open forests of the Transition Zone. Somewhat similar to the silver gray squirrel, Sciurus griseus griseus Ord, which is rare within the Park, the gray digger is distinguished by his less bushy tail and the conspicuous black patch which extends from between the shoulders to the middle of his back. In addition, the silver gray squirrel usually stays fairly high in the trees, while the ground squirrels rarely climb more than a few feet off the ground.

On June 12, 1952 a muskrat (CLNP #519) was found by Chief Ranger L. W. Hallock and Assistant Chief Ranger James W. B. Packard, frozen in a snow bank about twenty-five yards east of the intersection of the north road with the rim drive. Later this year, on July 24, a live muskrat was seen by Rangers Edmund J. Bucknall, John C. Wright, and Merrill H. Newman in the headlights of their car at the Annie Spring traffic circle. These are the most recent of several collections and observations which have been made since 1933 (Walks 1947:73).

Many of these records have been in areas in which it seems unlikely that muskrats, which prefer regions having abundant water, would establish permanent homes. However, the known occurrence of three of these animals within the park in the last two years would lead one to suspect that they have become established in one or more restricted localities (Yocom 1951). Since the natural range of the native muskrats does not extend into this region, the most reasonable explanation as to the origin of these individuals is that they are descendants of animals which were introduced several years ago in the Upper Klamath Lake region for purposes of fur farming (Huestis 1938).

References

Canfield, David H. 1933. Gleamings [sic] of the Chief Ranger. Nature Notes from Crater Lake National Park, 6(1):12.

Huestis, Ralph R. 1938. Muskrats in Crater Lake National Park. Nature Notes from Crater Lake National Park, 11(2):22-23.

Wallis, Orthello L. 1947. A Study of the Mammals of Crater Lake National Park. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Oregon State College, Corvallis. 91 pp.

Yocom, Charles F. 1951. Muskrat Record. Crater Lake Nature Notes, 17: 9.

Fairy Shrimp

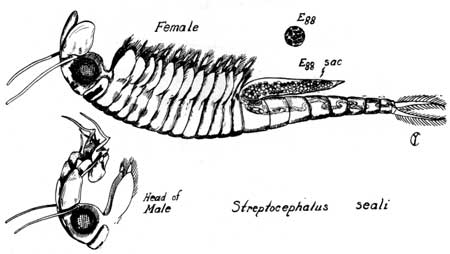

Pen and ink sketch of Fairy Shrimp by Ranger-Naturalist Charles F. Yocum.

On July 27, while making some investigations of a group of small, shallow ponds on top of Whitehorse Bluff, the author, with Assistant Park Naturalist Donald S. Farner and Ranger-Naturalist James Kezer, found all five of the ponds visited thickly populated with fairy shrimp. Fairy shrimps belong to the animal group known as phyllopod crustaceans — small relatives of the crayfish, crab, and lobster. Many species of them are found only during the spring season, frequently in temporary ponds which may be in existence for only a few weeks. They emerge rapidly from eggs which were laid the previous season, soon grow to maturity, mate, lay their eggs, and thus complete their cycle.

Ranger-Naturalist Fairbanks collecting in a temporary pond on Whitehorse Bluff. Photograph by Art C. Toth. |

The Whitehorse ponds, four of which were sampled, lie at an approximate elevation 6250 feet above sea level. They are mostly temporary, and some of the basins were completely dry before mid-August. At the time of the first visit to them, they were being fed by water from melting snowbanks along their shores. None was over thirty inches deep, and they were nestled in a forest of lodgepole pine and mountain hemlock.

The first pond, so-called North Whitehorse Pond, did not at first appear to have any of the fairy shrimp, and none were noticed until we had moved on to the second. Closer examination of the first sample, however, revealed a large number of very small, immature specimens. It may possibly be that this pond was formed later than those in which older individuals were found, although there was no further evidence to indicate that this was the case.

All specimens mature enough to be identified proved to be Streptocephalus seali (See Figure). Thanks are due Dr. Ralph W. Dexter, Professor of Biology at Kent State University, Kent, Ohio for the identification. Thanks are due also to Ranger-Naturalist Charles Yocom for the illustration which accompanies this note.

This same species was found by Ranger-Naturalist Kezer in Lake West, a small, permanent body of water about a mile beyond the park boundary, just outside the northwest part of Crater Lake National Park. He first observed them there during the last week in September, 1951, when they occupied the entire lake. On July 24, 1952 he again found them. This time, however, they were confined to the northwest section of the lake.

“The Marble Halls of Oregon”

Oregon Caves, long known as the “Marble Halls of Oregon,” and 480 acres surrounding them were set aside as the Oregon Caves National Monument in 1909. Since 1934, the Monument has been administered by the National Park Service as an adjunct to Crater Lake National Park. Rooms, meals, and cave guide service are provided by a concessioner, the Oregon Caves Resort Company, operating under contract with the National Park Service.

The first record discovery of the caves was made by Elijah Davidson, while out hunting in the fall of 1874. Davidson wounded a bear with one of his shots and tracked the bear to an opening in the side of a mountain. With a few splinters of pitch for a torch, and with an old muzzle-loading rifle, Davidson followed the bear into the opening, thus making his remarkable discovery. It was not until the next spring that Davidson and a party of associates returned to explore the caverns further. Four different levels or floors were found by Frank M. Nickerson of nearby Kerby. A number of galleries were opened which had been blocked by stalactites and stalagmites, forming columns. It was not until 1884 that title to the caves was sought, when two brothers “squatted” near the entrance. Their attempt to exploit this natural wonder failed, due to the remoteness of the area, the nearest railroad being over 200 miles distant. A short time later, a group of California promoters became interested in developing the caves, but abandoned their plan when they discovered that they were located in Oregon instead of California.

The area was visited by Joaquin Miller, “Poet of the Sierras,” in 1907. Miller did much to attract public attention to the caves by his frequent reference to them as “The Marble Halls of Oregon.”

According to “Old Dick” Rowley, who inaugurated guide service at the caves in 1910, it was the particularly energetic efforts of a group of promoters, interested in exploiting the caves, which stimulated the Forest Service in Grant’s Pass and Portland early in 1909 to press the Federal Government to set the area aside as a National Monument. This was done by President Taft on July 12,1909, and the caves, along with 480 acres of beautifully wooded land comprised the Monument, which was administered by the Forest Service under the Department of Agriculture. It was not until 1934, that the Oregon Caves National Monument was transferred to the National Park Service, to be administered by the Superintendent of Crater Lake National Park.

Dick Rowley, long a resident of southwestern Oregon, who had engaged in mining, hunting, and forest- patrol in the vicinity, was selected by the Forest Service to serve as guide to the Caves. To Rowley goes the credit for the major development of the Caves. Until two years ago, “Old Dick,” as he is affectionately known to young and old, headed the guide service. During the past thirty years, Dick has trained over 300 seasonal guides. In spite of his 82 years, “Old Dick” still spends the early part of each season at the Monument, breaking in a new crop of guides. During his more than 40 years at the Caves, he has become exceedingly familiar with the topography, flora, and fauna of the Monument. He assisted Dr. Elmer Applegate, the well-known botanist, in making a botanical survey of the Monument and the surrounding region. This survey, revealing rare species of trees outside the Monument, has served as a major basis for the current consideration being given to expanding the area.

The geological story of Oregon Caves goes back over a vast period of time to an age when an ancient ocean covered the southwestern part of Oregon. Over the floor of this ocean, thick deposits of lime were laid down and eventually pressed into limestone. This limestone, during a period of mountain building, was transformed, under terrific pressure and heat generated within the earth, into marble and was raised above the sea as a part of a mountain range.

During the mountain uplift, the marble was broken and fractured in many places. Although they may have been small, these openings were sufficient to allow water to seep into them. Rain water and water from melting ice and snow leached carbonic and other acids from decaying vegetation. Such acid-charged water found its way along the small fracture planes, and with the patience of the ages, dissolved out the softer portions of the marble in the interior of the mountains, thus creating giant chambers and extensive passage ways. The present visited section, Oregon Caves, makes up the most spectacular known part. Within these caverns are to be found the usual features of marble caves, such as stalactites, stalagmites, frescoed ceilings, and smoothly-paved marble floors. Some of the formations resemble flowers, vegetables, frozen waterfalls, and even animals, all of which have been given fanciful names.

Photograph Courtesy Laurie Ann Creations, Edmonds, Wash.

In addition to this exhibit of marble sculpturing, Oregon Caves National Monument boasts of one of the most beautiful and interesting wooded areas in this part of North America. It is rich in the variety of plant and animal life. Many species of plants find the caves area the southern limit of their range, while species otherwise limited to California, find here the northern limit of their range. The area includes transition, Canadian, and Lower Hudsonian zones. Because of the extremely broken topography, species are often found here outside of their normal habitat. Thus the drought-loving incense cedar occurs on high dry ridges along with mountain hemlock and noble fir. Among the more noteworthy species of trees within the Monument are the Port Orford Cedar, Tanbark Oak, Chinquapin, Knobcone Pine, and green- leaved Manzanita. On the north slopes occur pure strands of Douglas fir with sparse undercover. In addition, there are to be found sugar pine, grand fir, Oregon Maple, Nuttall’s dogwood, California hazel, and Sadler’s oak. The weeping spruce, (Picea breweriana), a tree of exceptional beauty, does not occur in the Monument, but is to be found in the area just outside to the South. It is to include such species of beauty and rarity, that the current plans for expanding the Monument are being pressed.

Among the fauna of the area, are to be found blacktailed deer, black bear, cougar, coyote, beaver, fisher, marten, Pacific mink, Pacific raccoon, gray fox, Douglas pine squirrel, silver-gray squirrel, Siskiyou chipmunk, and the golden-mantled ground squirrel. There is also an abundance of birds in numbers and species due to the diversity of cover types, making this an attractive spot for the bird lover.

Oregon Caves National Monument is located in the heart of the Siskiyous, 50 miles from Grants Pass. From Cave Junction, on the famous Redwood Highway, No. 199, it is only 20 miles to the Monument over scenic State Highway No. 46. The National Park Service maintains a parking area and picnic grounds nearby. No camping is permitted in the Monument, but adequate campground facilities are located at Greyback campground along the approach highway, 8 miles from the Monument. During the summer season, the concessioner operates a modern Chateau and cabins near the entrance of the Caves.

Other pages in this section