I got one shot of him with the 500 mm, and with the click of the shutter he vanished back of the ridge. We saw no more of him that day, but during the following two weeks my wife and I had the opportunity of observing the entire fox family and photographing them around their various dens as they moved farther and farther away from human interference. The three young ones became for a time almost indifferent to our presence, because, as is well known, the parent foxes have a great deal of difficulty in teaching their young to be afraid. We eventually were able to photograph all three of the young almost at will, but were able to get only distant shots of the wary adults. In this connection it is of interest to note that whereas most male carnivores will eat their young if given the opportunity, the male red fox helps take care of the young until they are able to take care of themselves.

The last time we visited their den, on July the 23rd, we saw no sign of the young foxes, nor did we hear the peculiarly eerie wild barking of the parents in the deep hemlock forest below the ridge.

In the meantime, on July 18th, former Superintendent E. P. Leavitt told us about a bald eagle’s nest at Diamond Lake, and we went with him immediately to locate it. He had only visited the locality once and then by boat from Diamond Lake Lodge, and as the lake was too rough to take a boat out that day, we drove around to the near vicinity, but could not identify the nest.

Returning two days later, we inquired at the fish hatchery whether anyone knew where the eagle’s nest was, and were promptly offered a boat ride across the lake by Jay Hoover of the Fish and Game, who knew where it was, and who landed us on the marshy shore about a hundred yards from the one hundred fifty foot fir in the top of which could be plainly seen the clutter of sticks we were looking for. For a half an hour or so there was no sign of life in the dense forest in which we found ourselves except for the clouds of mosquitoes which seemed to be impervious to the insect repellent we had with us.

Looking almost directly up at the nest we could see no young in it and the adults were apparently out over the lake at the time, so we occupied ourselves with a close-up telephoto shot of the nest to show its construction, and also general habitat shots.

While so doing we suddenly heard at some distance through the trees the weird, loud cacaphony of the adult eagle’s cry of alarm. Moving in that direction we almost immediately came upon an extremely exciting spectacle. Close together in the high top of a dead Douglas fir, with white heads and tails gleaming in the sun were two great bald eagles. We were able to get two good shots of them before either their excitement or ours caused them suddenly to soar away out of sight.

Two-year old bald eagle. From a kodachrome by Ranger-Naturalist Ralph Welles and Florence Welles.

Later that afternoon we made two discoveries that facilitated observation and picture-taking of our quarry. There was a narrow opening in the forest through which the nest could be seen from the road, and secondly, by climbing the mountain on the other side of the road about fifty yards we found that we could observe not only the nest but that there were two very young but not small nor “baldheaded” eagles in it. Although it was to be several weeks before “the babies” could fly, they were already nearly as large as their parents and their heads were still as dark as the rest of them as they would continue to be for three or four years.

From our view-point on the mountain we set up our 500 mm and 640 mm cameras and waited. It was two hours before we had the gratification of seeing and photographing a parent eagle swoop down with breath- taking swiftness and alight on the edge of the six-foot nest and proceed to tear up what appeared to be a large white bird and feed it to the young.

We saw them at weekly intervals up until the time of this writing. When last we observed them one of the adults was no longer putting in an appearance, the young were learning to fly, stretching and flapping their great wings (they already had a wing-spread of approximately six feet), sometimes rising two or three feet, then settling back down.

A more complete record of our experience with the great gray owl is contained elsewhere in this issue of Nature Notes.

It would be easy, not to say delightful, to spend an entire summer photographing the golden mantled ground squirrel, the Olympic black bear or the Clark nutcracker. A book could be written about how we came into possession of a great horned owl which we eventually banded (with the help of Ranger-Naturalist Wally Ernst, who was of invaluable aid to us on that and many other occasions) and turned loose on Dutton Ridge. I could write about the courage and tenacity for life of the badger that we found stunned and bleeding on the road where he had been struck by a passing vehicle.

You can see pictures of these and many others and hear their story when you attend the Naturalist talks at Crater Lake National Park.

Indian Relics on Mt. Mazama

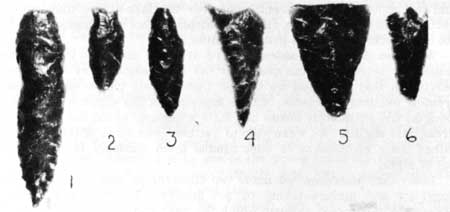

Fig. 2 |

On August 11, 1952 an arrowhead (Fig. 2) was brought to the Information Building by a visitor who had found it that morning at the viewpoint near Discovery Point, not far from the plaque which calls attention to glacial scratches on rock at the Rim. It is quite possible that this arrowhead was exposed by the heavy thundershowers which occurred during a four-day period shortly before the day on which it was found. This becomes the seventh Indian point in the park collection, earlier finds having been made in Godfrey Glen (Fig. 1, Nos. 1,2,3) along the first turn in the highway leaving the Rim Village (Fig. 1, No. 4) and on the upper part of the Garfield Peak Trail (Fig. 1, Nos. 5,6). The unique feature of this arrowhead is that it has been made from opaque whitish-colored rock, whereas all of the others are of are of translucent obsidian.

The Indians which once lived in this region are known to have been superstitious of Crater Lake and Mt. Mazama, considering the area to be the home and battleground of the gods. For this reason they established their camps a considerable distance away from the mountain and seldom ventured near this sacred abode. One of their legends, however, provides some clear evidence they occasionally hunted in the forests on the slopes of Mt. Mazama itself (Homuth, 1929). Our growing collection of Indian points contributes significantly to the belief that this and other Indian legends concerning Mt. Mazama may contain considerable basis in fact.

Reference

Homuth, Earl U. 1929. An Indian Legend. Nature Notes from Crater Lake, 2(3):2-3.