Crater Lake Waters

Each year, some three hundred seventy thousand visitors make their way to Crater Lake National Park. While their reasons for coming, and what they see and remember of the park, are doubtless as many and varied as are the visitors themselves, it is safe to say that, with very few exceptions, the center of their interest is Crater Lake itself. These beautiful waters – their color describable only as Crater Lake Blue — rest in the top of an ancient mountain whose summit was destroyed about 6,500 years ago.

An occasional visitor will step up to the rim, take a quick look, and say to his companion, “Well, we’ve seen it. Let’s go.” More often, however, the lake excites curiosity and prompts questions such as, “How did it come to be?,” “How deep is it?,” “How cold is it?,” “Are there fish in the lake?,” “Does it have an outlet?” and, “Does the water level vary?” The one of particular interest here is the last.

Although Crater Lake, deepest in the United States, was first seen by white man in 1853, dissemination of information was then so limited that two later, independent “discoveries” were made — in 1862 and 1865 (Runkel, 1953). Also, no serious scientific investigations within the area eventually to become Crater Lake National Park were made until the visit of the Joseph Diller party in the summer of 1886. At this time, the first Geological Survey map was constructed, soundings and temperatures of the lake waters were taken, and foundations were laid for what is now called the geologic story of Crater Lake. It was then that the deepest sounding of 1,996 feet was made.

Since that time, other soundings — notably those of John E. Doerr in 1939, then Park Naturalist at Crater Lake National Park and currently Chief Naturalist for the National Park Service — and studies of lake levels have been made. The earliest water-level records, aside from Diller’s of 1886, are largely obscure and of somewhat uncertain accuracy. Several are derived from names and dates painted by occasional visitors on rocks at the water’s edge. Some of these, however, are more or less readily relatable to later-established, known elevations and can be accepted with some validity.

The early picture is further confused by differences, unresolved by data presently available, in basic elevations established by the Diller party as compared with those on the current topographic map. For example, the lake-surface elevation, a figure subject to various types of fluctuations, was recorded for 1886 (Diller and Patton, 1902) as being 6,239 feet above sea level. This amounts to a difference of sixty-two feet from the 6,177 feet given on the most recent topographic map. Furthermore, all elevations of known stable points are of a magnitude greater than those on this 1946 edition – as well as on other available maps dating later than 1886. The disparities on specific points vary from as little as twelve feet to well over one hundred feet. It is understood, however, that elevations of many points throughout the western United States have been revised downward since Diller’s work. In order to arrive at a comparable figure, the differences of seven prominent rim points were averaged. This figure, seventy-one feet, was then subtracted from the 6,239 feet given for the lake level. The result is 6,168 feet, a value that falls nearly in the middle of the observed range of lake levels.

The first water gage on the shore of Crater Lake was erected for the Mazamas, a mountaineering club of Portland, Oregon, on August 22, 1896 (Diller and Patton, 1902). Diller states that it “was made of a board 5- 3/4 inches wide and 10 feet long, with scale subdivided to tenths of a foot. It was nailed to a log extending from the shore into the water, and zero of the scale was placed just 4 feet beneath the water surface, . . . Fearing that this fragile gage might not escape accident from rolling stones and sliding snow, W. W. Nickerson, of Klamath Falls, was requested to insert a bolt in a cliff near the gage and carefully determine the height of the bolt above the water and read the gage.”

The Nickerson bolt, a copper pin, was placed in position on September 25, 1896. The precaution was a good one, as the Mazama gage was cast adrift that winter, and the record book, contained in a copper box, was not recovered until five years later, on August 13, 1901. Two of Diller’s associates found it in Danger Bay in five feet of water, three and one half miles from Eagle Cove, the original location (Diller and Patton, 1902) The records were intact.

Diller, by referring to the record book, then painted a scale with the same zero point on a nearby rock face and inserted a pin, now known as the Diller Pin and still in place, at a point eight feet above zero point – four feet above the water level at the time that the original gage was installed. Diller (Diller and Patton, 1902) relates numerous water-level readings, including several incidental ones previously mentioned, to the Mazama gage. The earliest of these was September 10, 1892, when the water stood at 4.142 feet. The lowest such record reported by Diller was for September 26, 1893, when it was 2.52 feet, or 1.48 feet lower than the 1896 figure.

Since that time, four other gages — including the most recent, placed October 3, 1952 – have been installed and numerous readings taken, although not with complete regularity. It is evident that the earliest records were not related to elevations as were those of later years. Young (1952) indicates that in 1908 a U. S. G. S. benchmark, giving an elevation of 6,179 feet, was set near the water’s edge. It was from this benchmark that the levels of August 19, 1916, taken by F. F. Henshaw, District U. S. G. S. Engineer, were established. On the basis of his findings, the zero (datum) for the Mazama gage is placed at 6,173.64 feet above sea level. This places the oldest known related level (September 10, 1892) at 6,177.78 feet, and the 1896 level, when the Mazama gage was installed, at 6,177.64 feet. It is interesting to note here (Young, 1952) that the lake level reported by Diller — 6,178.545 feet, July 1, 1901 – records the lake at its maximum observed stage.

Records of lake level compiled by Ranger W. T. Frost (1937a, 1937b) indicate the level as remaining fairly constant. The greatest annual variation during the period of years from 1908 to 1913 was only 1.55 feet. No records were shown for the war years, 1914-1917. In 1918 there appears the beginning of a prolonged decline, which may actually have begun in the four previous years.

Frost’s notations carry through the year 1936 and show a general decrease in precipitation, correlated with the drop in lake level. He stated that the “Lake level is falling at an average rate of .51 foot per year. (Estimated from figures over a 26 year period).” He also stated that the average seasonal variation was 1.55 feet. In this connection, Diller (Diller and Patton, 1902) states that the annual “oscillation is limited to about 4 feet.” He says further that “the rising and sinking balance each other so that the lake maintains in general the same level.” This appears to be essentially true.

It seems possible that the annual fluctuation quoted from Frost may be somewhat less than total, since the lake is at its highest — usually in May or June — when it is least accessible for obtaining data. This appears to be the reason for Diller’s estimate of a maximum of four feet. Paul Herron, boat operator and engineer for the Crater Lake National Park Company, reported that the lake level for the 1954 season remained fairly constant at 6,176.9 feet during the first twenty days of June, after which it began to recede gradually. The last reading taken prior to the time of this writing was made on August 18; this report was 6,176.26 feet, representing a drop of 0.64 foot in approximately two months. The lowest level, however, should be expected at sometime in October, after the beginning of fall rains and snows.

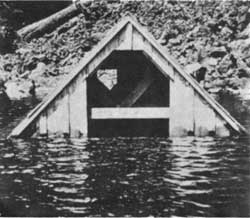

In the fall of 1942, the sills of this 10-foot high boathouse stood 18 inches above the lake water level. From a Kodachrome, taken in August, 1954, by C. Warren Fairbanks |

Recession of the lake level during these years, 1918-1936, continued until 1940, when the all-time low of 6,162.3 feet was recorded (Young, 1952). From that date until the present, Crater Lake has risen steadily, for an observed total of 14.6 feet in fourteen years — an average of 1.043 feet per year. The level this year falls within the range of high levels which extended from the 1890’s through 1913.

As has been mentioned previously, the highest observed level was recorded by Diller in 1901. This figure of 6,178.545 feet, when considered together with the 1940 low, indicates an all-time observed fluctuation of 16.245 feet.

There is, however, some evidence of a higher level at some time in past. Gordon Hegeness (Williams, 1942), formerly a Ranger Naturalist at Crater Lake National Park, found a deposit of diatoms — microscopic water plants which have siliceous walls — on Wizard Island, approximately fifty feet above the water level. Williams uses this evidence to assume a former high level of that approximate magnitude. The location of this find apparently was not recorded, and analysis of that material to determine its significance has not been possible. Investigations carried out this summer, however, have contributed significantly to our knowledge on this point; the results are reported upon elsewhere in this issue (Rowley and Showalter, 1954).

There is some evidence from another source which indicates a slightly higher level in the past. A definite line formed by the drowning-out of lichens — primitive plants which can gain a foothold on bare rock faces – is observable a few feet above the present water surface.

Young (1952) uses field notes of F. F. Henshaw and of J. S. Brode, another former member of the naturalist staff at Crater Lake National Park, to arrive at the figure of 6,180.9 feet as the probable highest level of the lake, at least in recent decades.

Thus it may be seen that the surface level of Crater Lake fluctuates in response to both seasonal and climatic variations. The former, resulting primarily from differences in the amounts of precipitation and run-off at various times of the year, occur relatively rapidly but are moderate in range. The latter operates over longer periods of time but are ultimately responsible for greater extremes.

References

Diller, Joseph S., and Horace B. Patton. 1902. The Geology and Petrography of Crater Lake National Park. Washington, Government Printing Office. 167, iii pp.

Frost, W. T. 1937a. Snowfall — precipitation and lake levels. Crater Lake National Park Nature Notes 10(1):3-7.

—–. 1937b. Errata. Crater Lake National Park Nature Notes 10(3):43.

Rowley, John R., and Wendell V. Showalter. 1954. Wizard Island, an index to the past?Nature Notes from Crater Lake 20:26-31.

Runkel, H. John. 1953. Crater Lake discovery centennial. Nature Notes from Crater Lake19:4-9.

Williams, Howell. 1942. The Geology of Crater Lake National Park, Oregon. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication 540. Washington, D. C., Carnegie Institution of Washington. vi, 162 pp.

Young, Charles A. 1952. Report on Crater Lake gages and elevations from 1892-1951. (MS. in Naturalist Files, Crater Lake National Park Naturalist Office).

Tribute to the Clarity of Crater Lake

The depth below the surface to which green plants are able to penetrate depends primarily on the availability of light, which is essential for photosynthesis. Turbidity, color, and amount of surface disturbance are the prime factors in determining the depth to which sufficient light for photosynthesis will penetrate. Based in large part upon these conditions, green plants occupy what is termed the photosynthetic zone, the upper six to seventeen feet (two to five meters) of water in most lakes. The growth of mosses at a depth greater than 400 feet (122 meters) in Crater Lake is therefore a tribute to the clarity of its water.

Peters grapple used by the authors |

Hasler (1938), a member of the naturalist staff at Crater Lake National Park during the summers of 1937 and 1938, states that, “The most startling biological finding at Crater Lake was the collection, by dredge, of green mosses…at the astonishing depth of 394 feet (120 meters). This is the greatest depth that growing green plants have been known to live in any fresh water body.” (Hasler, 1937).

Collections made this past summer, using the grapple pictured, confirm and extend Hasler’s findings, which indicated that green plants cover a large part of the bottom of Crater Lake down to a remarkable depth. Mosses were collected by the authors from maximum depths of 384 feet (117 meters) in Cleetwood Cove, 410 feet (125 meters) at a point south of Wizard Island, and 425 feet (129 meters) at a place south of the Wineglass. In fact, very few attempts below 110 feet failed to be rewarding in this respect. Material from this 425 foot collection has been identified asDrepanocladus fluitans (Hedw.) Warnst. by Dr. Francis Drouet, Curator of Cryptogamic Botany, Chicago Natural History Museum, to whom appreciation is expressed for making this determination.

These figures do not necessarily represent maximum depths at which mosses occur in Crater Lake. They represent, rather, near-maximum working depths attainable with the 450 feet of cable available for the operations. Two other factors need to be considered in interpreting these figures: (1) the difficulty in locating a portion of the generally steep-sloping lake bottom that allows full use of the equipment, and (2) the difficulty in then maneuvering a small boat so as to remain over such a spot.

The minimum depth at which mosses occur in Crater Lake appears to be more definable. Hasler (1938) found no moss above a depth of sixty feet, and the least depth at which we recovered mosses was eighty-five feet. In some areas, such as at Cleetwood Cove and Eagle Cove, no mosses were obtained at depths less than 110 feet.

It is difficult to suggest valid reasons for such findings. Wave action could be a factor, although the situation at Fumarole Bay, which is quite protected and in which mosses are not found at lesser depths than elsewhere in the lake, would seem to preclude this explanation. Another possibility is that the species may be light intolerant. Collections of mosses made from a log (Brode, 1938; Fairbanks, 1953), called the “Old Man of the Lake,” that has been floating about the lake for many years in a vertical, “dead-head” position, would seem to lend doubt to such a conclusion. It appears that this problem will not yield to simple explanation and will have to await further investigation.

References

Brode, J. Stanley. 1938. The denizens of Crater Lake. Northwest Sci. 12(3):50-57.

Fairbanks, C. Warren. 1953. The Crater Lake community. Nature Notes from Crater Lake 19:21-25.

Hasler, Arthur D. 1937. Preliminary report on bottom flora and fauna of Crater Lake. (MS. in Crater Lake National Park Library).

—–. 1938. Fish biology and limnology of Crater Lake, Oregon. Journ. Wildlife Management 2(3):94-103.

Aquatic Flowering Plants of Crater Lake

Frederick V. Coville (1897) reported that in 1896, “The Lake itself is wholly devoid of aquatic vegetation. No algae, no mosses, and no aquatic flowering plants were found in its water.” Crater Lake is now known to support a large number of small (microscopic) animals and plants, and the lake bottom, at depths of 60 to 425 feet, appears almost everywhere to have a thick covering of mosses. The types of aquatic flowering plants thus far discovered in Crater Lake, however, are limited to a very small number.

During the summer of 1954, six different species of flowering plants were observed in the lake. Water buttercup, Ranunculus aquatilis L. var. capillaceus (Thuill.) DC., occurred in several large beds eight to ten feet below the lake surface in the northeastern corner of Fumarole Bay, on the western side of Wizard Island. One solitary emergent plant was found close to the shore of the island. This individual bloomed on August 17.

Water buttercup was collected by Brode (1938) near this same location in 1935. Until this summer, it was regarded as the only aquatic flowering plant in Crater Lake.

Two other plants were growing, both submersed and emergent, in the same part of the lake. A member of the mustard family, tentatively identified as Pennsylvania bitter-cress, Cardamine pennsylvanica Muhl., was rooted as much as a foot below the surface. When first observed, early in August, none of the fifteen to twenty individuals found had emergent leaves or stems. Later that month, the leaves of several plants had extended above the water. High winds in early September severely damaged these plants, and when last observed, on September 10, none had flowered. Two plants, however, which had been transplanted to an aquarium at Park Headquarters produced flowers and fruits.

Baltic Rush near Wizard Island. Photo by C. Warren Fairbanks.

This little mustard had an enormous amount of root development for its size. This feature is undoubtedly important in its moderate success, thus far, on the rocky and inhospitable bottom of Crater Lake. The tuber- like root and its many smaller rootlets were, in fact, not rooted in the usual sense at all but were merely entwined about these rocks.

Rather extensive groups of a rush, Juncus balticus Willd., were rooted below the water in at least four different spots in or adjacent to Fumarole Bay. In each of these areas, part of the rush growth is above water. This Baltic rush, in common with most other rushes, multiplies both by seeds and by runners (rhizomes) under soil or water. Hence, its spread from the damp, semi-aquatic shore into the water – or vice versa – could be expected. It is likely that the roots of the highest plants were submersed during the spring high-water level (cf. Fairbanks, 1954). Both the Baltic rush and the Pennsylvania bitter-cress are found in several other locations in the park outside the caldera and are common in wet places along the Pacific Coast.

At least one species of willow, Salix coulteri And., and the red elderberry, Sambucus racemosa L. var. callicarpa Greene, were occasionally found near and in the water. Both of these are sometimes considered to be aquatic plants since they are water tolerant; one Coulter willow is rooted in eight feet of water. There is evidence, however, that they are being drowned by the increase in water level since 1940. At that time, the lake was slightly more than fourteen feet below its present average elevation of 6,176 feet above sea level (Fairbanks, 1954). There were no young plants noted in the water.

Fennel-leaved pondweed, Potamogeton pectinatus L., was found growing in abundance on the bottom at depths of ten to fifteen feet in a channel near the westernmost extension of the Wizard Island block lava flow into Skell Channel. The portion of this channel supporting this pondweed would undoubtedly have been a pool in 1940 when the lake was fourteen feet below its present level. Since the bottom is now twenty feet below the surface and has a layer of diatomaceous ooze as much as three inches in thickness on top, a long period of submersion is suggested.

Sago, or fennel-leaved, pondweed is cosmopolitan in its distribution, being found in fresh or saline waters from sea level to 7,000 feet in elevation. Although this plant has not been observed previously in Crater Lake National Park, its presence now is not particularly surprising.

This pondweed is considered to be an important food for waterfowl. There is a small, pea-sized tuber at the base of its stem. It is abundant in many ponds and lakes, such as Upper Klamath Lake only a relatively few miles to the southeast. It may, therefore, be fairly safely assumed that ducks and other water birds occasionally carry around such plants on their feet. Eventually a hitch-hiking pondweed could be expected to drop off into Crater Lake in a location which would provide protection from wind and wave action and which would supply a sufficiently favorable bottom for its establishment and reproduction. Of course, it may have arrived in some entirely different manner.

In this connection, it might be mentioned that Crater Lake at present has very few areas where the bottom is both sufficiently shallow and adequately protected to offer a favorable environment for colonization by aquatic flowering plants. It is true that a shelf has developed under much of the lake edge at the base of the rim wall. However, the major factors responsible for the formation of the shelf — falling debris from the steep wall above, and wave action — tend to deter the successful establishment of plants. These are undoubtedly among the more important reasons why the waters adjacent to Wizard Island support most of the aquatic flowering plants found in Crater Lake. The greater stability of the debris near the shore of Wizard Island greatly reduces the amount of disturbance caused by this factor in the underwater shelf around the island. The greater irregularity of the shore line around Wizard Island – with its small but numerous inlets, bays, promontories and off-shore islets, especially in the Fumarole Bay area — undoubtedly contributes toward a considerable reduction in the intensity of wave action. These two factors would therefore tend to produce around the island areas much more favorable to the establishment of aquatic flowering plants than any area along the shore of the rim wall.

The concentration of these plants in the Fumarole Bay area of Wizard Island is no doubt also a result of the greater accessibility of this western side of the island to plants. Wizard Island here approaches most closely the wall of the caldera itself, the distance across Skell Channel at its narrowest being approximately three hundred feet. The water between the island and the caldera shore is also at its shallowest in this channel. Changes in lake level would therefore operate most effectively here in exposing additional land surface which could act as a passageway for migrating plants.

It has been suggested many times (Shelford, 1918) that the quantity of plant and animal life increases with the age of water bodies, especially where the outlet is small. If this is true, the number of aquatic flowering plants in Crater Lake could be expected to increase steadily and perhaps quite rapidly. This would be due not only to the fact that it is a relatively young lake, but also to the fact that the lake level may remain fairly constant, with the exception of seasonal variations, for several successive years. This latter factor would perhaps tend to operate in the same manner as a small outlet and, in any case, would contribute favorably to the establishment of new species.

Thus it is possible that Coville’s reference to a complete lack of plants in Crater Lake, although undoubtedly not strictly true, may have been very nearly so in 1896. There is ample evidence, from other regions that have been formed by volcanic eruptions, for radical changes of this sort within a period of fifty years.

Except for the trees that come down to the shore line on parts of the caldera wall and on Wizard Island, the lake appears — even after some exploration — to be quite barren. Who would suspect that from less than one hundred feet to more than four hundred feet below the surface there grows a lush mat of mosses in every place in which we have grappled so far? Furthermore, how many would realize that these mosses harbor an even greater number of smaller plants — algae — and animals?

Specimens of these aquatic plants are deposited in the herbarium at Park Headquarters, Crater Lake National Park. Perhaps you would like to know some of them better but will not be able to meet them first-hand in the lake. You will be welcomed at the park herbarium if you are particularly interested in these plants.

References

Brode. J. Stanley. 1938. The denizens of Crater Lake. Northwest Sci. 12(3):50-57.

Coville, F. V. 1897. The August vegetation of Mount Mazama, Oregon. Mazama1(2):170-203.

Fairbanks,. C. Warren. Crater Lake waters. Nature Notes from Crater Lake 20:31-35.

Shelford, V. E. 1918. Conditions of existence. In: Ward, H. B., and G. C. Whipple. Fresh-water Biology. New York, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ix, 1111 pp.

Other pages in this section