At Home Along Lost Creek

By Mrs. Marcella Stine

We returned to Lost Creek on the 15th day of June, 1955. Almost immediately we found that a pair of yellow-bellied marmots,Marmota f. flaviventris (Audubon and Bachman), had made their home under the old barn. During the summer we watched their comings and goings with a great deal of interest.

On July 9th, I happened to walk by the barn and, much to my surprise, saw two baby marmots. Upon looking around I found two more babies. I hurried home to tell my family of the discovery, and together we went over to watch them. After a few minutes the babies began to appear first came the four, then another, and finally three more. Eight baby marmots! They were very unsteady on their legs and fell all over each other as they played.

They seemed not to know the meaning of fear and paid no attention to us. Suddenly we heard a loud thumping of feet as one parent came rushing through the grass. The babies scurried into their home — all except one curious little fellow. He apparently decided to have another look. All at once he let out a sharp squeal and backed into his home. I feel reasonably sure that mamma spanked.

After lunch we again went over to watch the babies and to count them once more. 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 – 5 – 6 – 7 – 8 – 9–my daughter Sandy counted 10. Goodness, that just couldn’t be — ten in one family? There were two adults; these must have been the parents. Surely there wouldn’t be two mothers and no father? They were all out now, playing like kittens. We counted again. Sure enough, there were ten. We sat about ten feet away, watching them play until the parents came home and shoved them in.

Much of the next three days was spent in taking pictures. I managed to get one which included all but two of the babies. By the end of the week they were venturing a hundred feet and more away from home.

Eight of the ten young marmots in the colony at Lost Creek; one out of sight at the left of the photo.

The adults were doing a fine job of teaching. The youngsters became more timid and would scurry into their home when we approached. The only way of getting pictures after July 17th was to catch them unaware — which was almost impossible — or with a telephoto lens. And how I wished that I had such a lens!

The barn stands in a direct line of sight from our cabin. With binoculars we continued to watch the marmots from our door. They still played quite a bit, but they scurried home at the slightest sound.

By the 20th of July, the young went with the adults in search of food. Then we would see them only in the early morning and after 5:00 p.m. During the last week in July there was no sign of either young or adults. I feel that they must have moved elsewhere, due to the many attempts made by visitors to capture them.

On August 14, I was surprised to see one of the young sunning itself behind the barn. I haven’t seen him since, although I have gone there frequently. I have seen evidence of many visits in which he returned with grass for his winter bed.

We have received so much pleasure from this marmot family that we hope very much to find another under the old barn next spring.

Editor’s note: According to Victor H. Cahalane (1947. Mammals of North America. New York, The Macmillan Co. x, 682 pp.), a marmot litter usually numbers four or five and has extremes of three to eight. A family of ten for a single mother would be very exceptional, although perhaps possible. However, frequent and intensive observation convinced Mrs. Stine that one of the two adults was a male. Furthermore, the presence of two females in an area with no evidence of any male would be rather unexpected, especially in view of the fact that yellow-bellied marmots are quite sociable animals. If one assumes that the two adults observed here were not both females and each mothers of a litter, it is also possible that one was a mother caring for, in addition to her own, the offspring of a family whose mother was killed, while the other was the father. In any event, this observation is an unusual and intriguing one. — R. M. B.

The Giant Meadow Mouse

By Orville Page, Ranger Naturalist

The meadow mouse is rarely seen in our park, especially in the daytime. On the morning of July 17, 1955, it was my privilege to observe for a few moments two mice which I am reasonably certain were giant meadow mice, Microtus richardsoni arvicoloides(Rhoads).

My destination was Godfrey Glen and Duwee Falls, in the steep-sided Annie Creek Canyon. A short distance above Godfrey Glen, I crossed a very lush meadow area. On the upper slopes of the meadow were some small springs which formed little streams of water about six inches wide and three inches deep. As I approached one of these streams, a splashing commotion was heard. This turned out to be caused by the two giant meadow mice. They seemed frightened by my intrusion and began to swim up the little stream. The mouse in the lead swam along for about eight feet and disappeared into the grass. The second mouse swam a little way and then hid under some grass that drooped over into the stream. Only his head was visible. He apparently felt insecure, and before my camera could be focused, he followed the other mouse on up the stream and disappeared.

Meadow mice are often found around water or damp places (Cahalane, 1947; Wallis, 1947). They are very good swimmers. One meadow mouse in Michigan was observed to swim about eighty feet, part of the way under water, to escape capture.

We have many little animals in the forest that are not seen unless one gets away from the thickly populated places. While out strolling through wooded areas, the lover of nature probably enjoys most those moments when he encounters some forest animal going about his daily living habits. These forest friends will continue to live in their natural surroundings as long as the National Parks maintain natural wilderness areas. The National Parks belong to you, as an American citizen. Only your constant vigilance will keep them in their present primeval setting.

Literature Cited

Cahalane, Victor H. 1947. Mammals of North America. New York, The Macmillan Co. x, 682 pp.

Wallis, Orthello L. 1947. A Study of the Mammals of Crater Lake National Park. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Oregon State College, Corvallis. 91 pp.

Woodpecker Activities

By Donald Van Tassel, Ranger Naturalist

Before the month of June was very old, I realized that this was going to be a good summer to get well acquainted with woodpeckers. Upon moving into the Annie Spring trailer court, the family of Seasonal Ranger J. Francis Stine informed me of recent activity by a male Arctic three-toed woodpecker, Picoides arcticus (Swainson), at his roosting hole in the center of the campground. This hole was located about twelve feet up in a live lodgepole pine. It was easily recognized as belonging to this bird because of the recent stripping of bark, forming a band about eighteen inches wide and nearly encircling the tree, at the same height as the hole. Only the male was seen, and he was usually gone all day.

Late in the morning of June 11, I waited for about an hour to see if there was any daytime activity, as I was hoping that this might be a nesting hole. The male finally came, pecking at the bark for two or three minutes before flying away again. No nesting there. I did hear and, after sneaking up the hill above the nest, see him giving the rapid, loud drumming on a dead branch of a tree which is usually associated with mating interests. This is the only record I have been able to find of a roosting hole in the park, and there is only one definite record of a nesting hole.

Soon after locating this hole, the high chatter of another woodpecker attracted my attention to a nesting hole located about thirty feet up in the dead, bleached-out snag of what seemed to be another lodgepole pine. The tree was standing within ten feet of the South Entrance road just across from the trailer court driveway. The bright red splotch of color on the top of this bird’s head quickly identified him as a hairy woodpecker, presumably Dendrocopus villosus orius (Oberholser). It was apparently a nesting hole, but because of the unstableness of the tree I had to be satisfied with climbing an adjacent tree about eight feet away for observation and pictures.

After a long and uncomfortable wait, the male accommodated me by flying to the nest. On two occasions I saw the male chase away an inquisitive red-breasted nuthatch, Sitta canadensis L., which may also have wanted a nesting hole. Many days later, and after many observations of the hole and the active male, I saw the female for the first time. Her appearance seemed to coincide with the first peeping of the newly-hatched young, about June 20. Although I wasn’t privileged to see all the family out of the nest at once, I took pictures of a nearly-grown male almost out of the hole on July 12, and from the noise within I would guess there were at least two other young. By July 19 there was no sign of the family at or near the hole.

June 17 I will long remember as the day I saw my first western pileated woodpecker, Dryocopus pileatus picinus (Bangs). This crow-sized, black bird with brilliant red crest and black-and-white striped neck swooped across the front of my car about four miles inside the park on the South Entrance road. He displayed his beauty while perched for a minute on a tree and then hurried away, giving his characteristic, loud, laughing cackle.

The very next day, while down in Annie Creek canyon near the South Entrance, I saw my first red-breasted sapsucker, Sphyrapicus varius dagetti Grinnell, very active about the mountain ash, Sorbus sitchensis M. Roem., and the black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpaTorr. and Gray. Upon revisiting this locality a month later, both parents were dividing their attention between feeding two immature birds — quite capable of flying around by themselves — and drinking the sap or eating the insects attracted by the sap oozing from the characteristic rows of square holes which they had pecked in the bark of the mountain ash. The young were also concentrating on pecking the ooze, so much so that I could approach within a few feet.

A momentary distraction from woodpeckers was occasioned by the loud peeping of an immature water ouzel or American dipper, Cinclus mexicanus unicolor Bonaparte, who was also being fed, on a log in midstream. He could hardly constrain himself when one of the parents would fly up bringing some insect tidbit.

In this same locality I noticed a pair of red-shafted flickers, Colaptes cafer (Gmelin), another member of the woodpecker family. Since they were on the other side of the stream I couldn’t check into their reason for favoring that particular area. They are the most conspicuous, if not the most abundant, woodpecker in the park, especially in the lower regions. On July 28, while escorting a field trip near the top of Garfield Peak Trail, I spotted one showing a brighter red than I had noticed before. On July 21 I saw a young flicker taking food from a parent about six miles inside the south boundary. While exploring Wizard Island for a few hours on August 6, I noticed what appeared to be a family group flying among the trees.

In order to round out my woodpecker experiences, I was eager to observe the fairly common Williamson sapsucker, Sphyrapicus thyroideus (Cassin), which is rather unusual in having a conspicuous contrast in color markings between the male and female. It was especially gratifying, then, to discover on July 12 a nesting hole containing young about forty feet up in a dead mountain hemlock near the Wineglass on the northeastern side of the lake. Both parents were in the feeding business and were quite disturbed when I scrambled up to look in the hole, even though I couldn’t see the young.

The Lewis woodpecker, Asyndesmus lewis (Gray), is also fairly abundant in the park, especially late in the summer. Last year I noticed them first on August 31, traveling in small flocks near Garfield Peak. They were evidently attracted to the area by flying insects or ripening berries. Such post-breeding movements to higher areas are common here.

Other woodpeckers uncommonly observed in the park are the alpine three-toed woodpecker, Picoides tridactylus (L.), the white-headed woodpecker, Dendrocopos albolarvatus (Cassin), and the red-naped sapsucker, Sphyrapicus varius nuchalis Baird.

Learning to recognize the members of a specific bird family and getting acquainted with their habits make a commonplace walk through the woods an adventure. Concentrating on the woodpeckers has guided my observations, and wherever I go I find a “family friend.” Now, even old snags, instead of seeming dubiously attractive, are noticed and suggest a potential home or a source of food for an unusual bird.

Perhaps you would like to choose a particular group of birds to concentrate your attention upon for a while. Here in Crater Lake National Park, Dr. Donald S. Farner’s The Birds of Crater Lakeshould prove an interesting and useful companion for your bird explorations.

References

Farner, Donald S. 1952. The Birds of Crater Lake National Park.Lawrence, University of Kansas Press. xi, 187 pp.

Gabrielson, Ira N., and Stanley G. Jewett. 1940. Birds of Oregon.Corvallis, Oregon State College Press. xxx, 650 pp.

Crater Lake Pines

Photos by C. Warren Fairbanks

Ponderosa pines near the South Entrance From Kodachrome by C. Warren Fairbanks |

There are many beautiful trees in Crater Lake National Park, many virgin areas untouched by the woodsman’s axe or the camper’s fire. Stately trees that have lived for centuries are here for the enjoyment of the park visitor, trees that will remain here for generations to come if the scourge of fire is kept out.

The pine tree has rather long, cylindrical needle-leaves that are clustered together in little bundles and are held together by a sheath at the base. The number of needles in the cluster is one of the characteristics used for identification of the different types of pines. The foliage is rather open, allowing the sun’s rays to make irregular splotches of light on the forest floor. The cones are more rough and coarse than those of the firs and hemlocks.

Crater Lake National Park boasts five beautiful species of pines. These trees grow throughout the area in belts, according to elevation, which may be referred to as Life Zones. The ponderosa pine, Pinus ponderosa Dougl., and the sugar pine, Pinus lambertiana Dougl., are found at the lowest elevations of the park. They grow in the Transition Zone, which runs up to about 5,500 feet elevation above sea level at this latitude. The Canadian Zone, which here ranges between about 5,500 and 6,200 feet, includes the lodgepole pine,Pinus contorta Dougl. var. latifolia Engelm., and the western white pine, Pinus monticola Dougl. The white-bark pine, Pinus albicaulisEngelm., is found in the highest elevations of the park, comprising the area referred to as the Hudsonian Zone. One should realize that there is considerable overlapping of these growing areas and that the above figures are quite general. They will vary considerably according to local conditions of exposure, sun and weather.

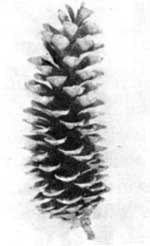

Ponderosa pine cone, x1/7 |

The beautiful ponderosa pine is the most outstanding pine of the park. As one enters from the south, these towering trees with their golden-brown bark, frame the roadway so magnificently that they are sometimes mistaken for giant redwoods. If one examines the large bark plates closely, he can readily see scales having shapes that might well remind him of a piece of an old jigsaw puzzle. These majestic trees are well named, these ponderous ponderosa pines.

Sugar pine cone, x1/7 |

The largest and most stately of all our pines is the sugar pine. It is both larger and taller than its close neighbor, the ponderosa. It received its name from the fact that, in scarred or burnt areas of its bark, it sometimes exudes a sugary resin. This the Indians particularly esteemed. The sugar pine is becoming quite scarce in logging regions. It is a favorite of the lumbermen because of its enormous size and its soft white wood. Fortunately, the trees in the park are protected from this fate.

Lodgepole pine cone, x1/7 |

The lodgepole is probably the most abundant pine in this area. In the southwestern part of the park it grows in dense groves. It is often referred to as “doghair pine,” because of its thick growth, and as “jack pine.” Lodgepole pine received this name because of its particular usefulness. The Rocky Mountain Indians used these slender trees for making their teepee poles and drag-sleds. The Plains Indians traveled hundreds of miles to secure these poles. More recently, the pioneers adapted this practice to the building of their cabins and lodges.

Western whie pine cone, x1/7 |

The cones are often sealed by a sticky resin which prevents release of the seeds. They may remain dormant within the cone for decades. Since growth is so thick, lodgepole pine forest has a high fire incidence. When fire sweeps through such a forest, the resin of the cone is melted and the seeds are freed to start a new grove. If fire is kept out long enough, gradually some of the larger, more shade-loving trees will work their way in and crowd out the slender lodgepole.

A very attractive but not so abundant tree is the western white pine. Often one will notice a dozen or more rather long, tapering cones near the top of this tree. If one examines the needles of the tree and finds them in bundles of five, he is readily assured of its identity as a white pine.

Whitebark pine cone, x1/7 |

The most beautiful, in a grotesque sort of way, is the white bark pine. The odd shapes of these trees are the result of exposure to the icy winds and winter snows at high elevations. Because of the severe weather it endures, this pine may be rather bushy and only three or four feet high, even though it is many decades old. It is often found growing in a crevice on some rocky ledge where it would appear that no tree would be able to survive. The seeds of its small purple cone are especially favored by nutcrackers and chipmunks.

These trees provide homes and food for many of the forest animals. These beautiful homes, centuries old, can be destroyed in a matter of minutes by someone’s carelessness. Let’s protect our trees and keep our parks and forests green.

Comparative Table of the Pines of Crater Lake National Park

| Name | Mature Size Height; diameter |

Mature Bark | Cone Length; width |

Needles Length; number |

| Ponderosa pine Pinus ponderosa |

60-125 ft. 2-2.5 ft. |

Large golden-brown plates | 3-6 in. 2-4 in. |

5-11 in. 3/bundle |

|

|

||||

| Sugar pine Pinus lambertania |

70-150 ft. 3-6 ft. |

Long plates; reddish brown to grayish brown | 10-20 in. 2.5-3.5 in. |

2.5-4 in. 5/bundle |

|

|

||||

| Lodgepole pine Pinus contortavar. latifolia |

30-50 ft. 2-6 in. |

Thin; silver-gray to black | 1-2 in. .75-1.5 in. |

2 in. 2/bundle |

|

|

||||

| Western white pine Pinus monticola |

50-100 ft. 1-3 ft. |

Small plates; silver-gray | 6-10 in. 2-3 in. |

2-4 in. 5/bundle |

|

|

||||

| White-bark pine Pinus albicaulis |

6-60 ft. 1-5 ft. |

Thin; silver-gray to white | 1-3 in. .75-2 in. purplish |

1-2.5 in. 5/bundle |

|

|

||||

References

Farner, Donald S. 1952. The Birds of Crater Lake National Park.Lawrence, University of Kansas Press. xi, 187 pp.

McMinn, Howard E., and Evelyn Maino. 1946. An Illustrated Manual of Pacific Coast Trees. Berkeley, University of California Press. xii, 409 pp.

Peattie, Donald C. 1953. A Natural History of Western Trees. Boston, Houghton Mifflin Company. xiv, 751 pp.

Sudworth, George B. 1908. Forest Trees of the Pacific Slope.Washington, D. C., Government Printing Office. 441 pp.

Charcoal Log Reidentified

By Richard M. Brown, Assistant Park Naturalist

The large section of a charcoal log which is now exhibited in the Information Building is apparently (Libbey, 1956) the same one as that which has previously (Anonymous, 1931:1) been referred to sugar pine (Pinus lambertiana Dougl.). Recent examination of material from this log has led Prof. D. W. Bensend (1956), Department of Forestry, Iowa State College, Ames, Iowa, to state that “one can say with a fair degree of certainty that it was ponderosa pine.”

This identification, as well as the earlier one, is in line with the summary which Williams (1942:113) has provided of the species represented by various pieces of charred wood collected in the immediate vicinity of Mt. Mazama. Appreciation is expressed to Dr. Bensend for this contribution to our information concerning the natural history of the Crater Lake area.

Literature Cited

Anonymous. 1931. Another page from the past discovered. Nature Notes from Crater Lake 4(2): 1- 2.

Bensend, D. W. 1956 (February 10). Letter in files of Park Naturalist, Crater Lake National Park, Oregon.

Libbey, D. S. 1956 (May 1). Personal communication.

Williams, Howell 1942. The Geology of Crater Lake National Park, Oregon. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication 540. Washington, D. C., Carnegie Institution of Washington. vi, 162 pp.

The Day Of The Great Gray Owl

By Florence Welles

On Tuesday, the 15th of July, 1952, we were not looking for the great gray owl. In fact, if we had been told that we might find and photograph a specimen of the large bird with a wing-spread of four and a half feet or more, we would have been most hesitant about believing it.

What took us from Crater Lake to an area of lodgepole pines a few miles west of Fort Klamath that day was the information that on a deserted farm known as “the old Turner place” we might find a coyote family. Our informant did not know the exact location of this family, but his idea seemed to be that it was living among the roots of a fallen tree. The prospect of seeing and, with luck, photographing coyote pups was an exciting one.

About the middle of the afternoon we arrived. Our first impression was that the woods were full of fallen trees. Which direction to take?

Would we have to wait for dusk when the mother coyote would be venturing forth in search of food for herself and her family, at which time we might be lucky enough to see her? We stopped the jeep near a group of forlorn and empty buildings in a clearing a half-mile in from the road The place seemed to sag all over, and the setting looked ideal for a Hallowe’en party.

At first, the only wildlife in evidence was a welcoming committee of mosquitoes, which no doubt changed shifts but which stayed with us throughout the hours we were there. Carrying the camera equipment that we do doesn’t leave a hand free for swatting! My husband was carrying the 500 mm. lens on a Leica which was mounted on a tripod, and I was carrying the 300 mm. lens, also on a tripod-mounted Leica. The forest floor was a criss-crossed tangle of fallen trees, and the going was rather rough. My husband struck off in one direction and I in another.

After intense looking for some time, I was suddenly aware of a slight movement and all at once found myself eye to eye with a porcupine only a few inches from me. He looked away quickly but continued to sit there, hunched over and perfectly quiet except for the gentle motion of his quills produced by his breathing. I spoke to him. No response. He just continued to ignore me and to stare off and away in what seemed to be a very rude and sullen manner. We already had pictures of both adult and young porcupines. So, as this fellow seemed not in the least interested in my company, I decided to move along. I looked back occasionally until he was out of sight. He still hadn’t moved.

I soon forgot him because it now seemed that a certain lodgepole pine just ahead of me was filled with a flock of small birds. Their chirping grew louder, and then softer, as I passed the tree. But where were the birds? Not a single bird could I see, although I searched each branch. I walked around the tree, and the noise grew louder again. Now I could see the spot from which it was coming. The little birds were not on the tree but in it. On tip-toe, I looked into a hole on the trunk. There was an immediate crescendo of chirping followed by complete silence. I could just make out three small heads. I thought longingly of our “strobe-light” outfit, which was miles away. I caught sight of my husband at some distance and signaled him to come and look. I watched with interest as he moved quickly and quietly over and around fallen trees with his unwieldy load of camera equipment. He looked in at the little birds. What kind of birds were they? If we waited, the mother would return and we would probably recognize her. The mosquitoes settled down on us– to wait, too.

The sun was getting so low that little light came through the forest now. We decided not to wait longer to identify our little birds but to resume our hunt for the coyotes. Our rising to leave was the cue for the tiny chorus to start up again inside the tree, and with some regret we went away.

A creaking among the high branches of the lodgepole pines told us that a wind was rising. Aside from that, there was hardly a sound as we moved along, still alert for any hint of the coyotes we were hunting.

Suddenly, in the branches above us and quite near, an excited chattering and commotion arose from a group of fluttering birds. What was it all about? We both moved cautiously and, peering up, almost immediately saw a giant owl which appeared to “fall off a limb,” as my husband later put it, not far above us. With seemingly noiseless and deliberate, slow strokes of his wings he alighted in another tree a short distance away. My first thought was, “There simply can’t be an owl that big!” — but there he was, still the center of attraction for the animated group of small birds which had followed him to his new perch.

After our initial amazement, the photographer came out in both of us. We realized that the light was poor and that what remained of it was fading rapidly. Much of the tree on which the owl was sitting was moving in the wind. We focused on him and hoped that a beam of sunlight would hit him. As we held our breaths and waited for this miracle, he decided to “fall off” again and float away to another tree. This happened four times, I believe, with the Welleses in perspiring pursuit.

At one point my husband ran back to the jeep for the longest and most powerful — and most cumbersome – lens, the 640 mm. He was back in record time, but of course by then our owl was off again, to a higher part of another tree, and the light was dimmer yet. We tried using a reflector, but the light under the trees wasn’t strong enough to be sent back up effectively. He moved again, and again we picked up all our equipment and followed him. This continued, with now and then a chance shot, until there was no further opportunity for getting an identifiable picture. At one point a sparrow hawk dived past the owl and provided a means of judging the latter’s size. The hawk appeared to be about the size of a swallow.

Dr. Donald S. Farner, Assistant Park Naturalist, sent kodachrome slides of our owl to Alden and Loye Miller for positive identification, and a letter received August 9th, 1952, indicated that there was no doubt that this was indeed the great gray owl, Scotiaptex nebulosa nebulosa (Forster).

Our last experience of the day was so improbable that I wonder if I should mention it at all. However, although it really happened, I think I would doubt it if I hadn’t actually been there. We loaded everything into the jeep and started away. It was almost dark. Suddenly my husband said, “Look over there!” Loping along like a moving shadow, was the unmistakable slinking form of the animal we had originally set out to find — a coyote!

What a day!

Postscript, 1954

We couldn’t have forgotten the events of the day just described even if we had tried. We knew that we had to go back, and it wasn’t just to see if we could find the great gray owl again. We had to admit that, in spite of large outlays of film and energy, fading light and rising wind had defeated us in getting a picture of the great gray owl that would serve for more than identification purposes.

Finally, on July 26, 1954, we spent another day in the same wildlife area, still deserted by human beings except for an occasional visit by the owner. He had told us that another family of coyotes had been born. We waited and we watched. If they were there, they remained well hidden under a tangled maze of fallen trees.

Birds were everywhere. We took many pictures, but the high point of the day was finding a great gray owl again. This time we think we have a picture that is really worthy of him.

Other pages in this section