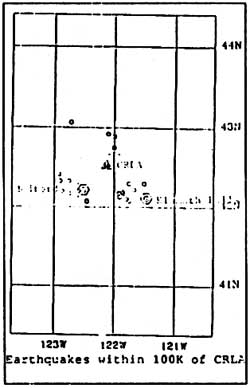

Earthquakes in the Crater Lake Area

Since 1865, there have been 44 earthquakes within a 100 kilometer (62 mile) radius from the center of Crater Lake. The highest magnitude of any quake occurring within the 100 km circle during this period was 4.3 on the Richter Scale. This reading was obtained on three occasions over the past 125 years: period: in 1920 (38km from the lake), in 1931 (77km), and in 1948 (55km). There are no magnitude records for 15 quakes occurring within the circle. They include the closest one, a quake that took place in October 1947, just eleven kilometers from Crater Lake.

Crater Lake does not appear to be the center of any significant seismic activity over the past century. Not only were the magnitude readings of lesser intensity, but there were only three quakes during the period that had their epicenters closer than 20km from the center of the lake. The next five closest quakes ranged from 35 to 39 kilometers; other quakes were 45km or further from Crater Lake. Average distance of the earthquakes from the lake was 55 km.

One chart shows their spatial distribution, with the center of Crater Lake being 42.57 north latitude and 122.07 west longitude. The other charts delineate epicenter distance from the park and quake magnitude.

Biodiversity in Red Blanket Canyon

Virtually all of the canyons in Crater Lake National Park are worth exploring. Many contain pinnacles or other interesting geological formations, but all of them are good hikes. As stream habitats, they harbor a greater diversity of life than the meadows, nonriparian forests, or pumice fields. The term biological diversity has been used to express the variety and variability among living organisms and the ecological complexes in which they occur. Diversity can be defined as the number of different items and their relative frequency. These items are organized at many levels, ranging from complete ecosystems (ecosystem diversity) to the chemical structures that are the molecular basis of heredity (genetic diversity).

Between ecosystem and genetic diversity lies species diversity, which refers to the variety of living organisms on earth. The most commonly accepted definition of a species is a population of organisms that can at least potentially breed with one another but that do not breed with other populations. Species diversity is a function of what the surrounding habitat allows. Wetlands and streams have long been known to harbor the greatest species diversity among the various habitat types. This is particularly evident as one hikes along the streams within Crater Lake National Park. For example, one could contrast the stream that originates at Boundary Springs with the adjacent lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) forest.

Of all the habitats within Crater Lake National Park, species diversity is greatest in Red Blanket Canyon. Only a small fraction of the canyon is within the park’s boundaries, but this is an environment very different from the subalpine, snow-adapted forest of Mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertsensiana) and true firs (Abies concolor, A. Iasiocarpa,and the A. magnifica-procera complex) that dominate so much of the park. The 4200 foot elevation of the park’s southwest corner is suitable for the growth and development of a mixed conifer forest. Its presence in the vicinity of Red Blanket Canyon was largely determined before 1900 through historic fire disturbances and the habitat type common to the Prospect area.

Some of the forest at the lower elevations in the canyon can be labeled old-growth, the kind of forest which once dominated the area between the Pacific Ocean and the crest of Oregon’s Cascade Range. Exact ecological definitions for these forests remain elusive, yet several of their structural components are easily discernable: large live trees, large snags, large logs on the ground, and large logs in streams. Greater structural diversity is evident than in younger stands, as old-growth trees have a much greater range of diameters, tend toward more heterogeneous spacing, and exhibit greater patchiness with respect to their understory vegetation.

The upper three miles of Red Blanket Canyon have a different species composition and function than the heavily logged forests of the lower Red Blanket drainage and the Prospect Flat area. As an old-growth forest, the upper canyon also displays differences in the rate and paths of energy flow. Likewise, it is distinct from stands further downstream in water and nutrient cycling. Maintenance of a large conifer overstory is critical to the survival of species not found in the younger forests, such as the Northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina) and the Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia). These species are fairly easy to discern and relatively large, characteristics which have been used as indicators in gauging the health of an increasingly fragmented life support system.

Red Blanket Canyon is accessible from Prospect or by using the trail system in Crater Lake National Park south of Highway 62. Most visitors go east of Prospect on Red Blanket Road to Forest Service Road 6205. The head of the canyon is roughly four miles up the gravel road, past a gate which is closed during the winter months. As one proceeds toward the Red Blanket trailhead located at road’s end, several regenerating clearcuts are periodically apparent near the stream. Roughly two miles short of the Red Blanket trailhead is a sign marking one end of the Varmint trail, which climbs through an old-growth forest and up the canyon’s north wall. Lightly used, the Varmint trail allows hikers to see the last roadless area adjacent to Crater Lake National Park not having legal wilderness designation.

The southwest corner of the park is encountered within a half mile of the Red Blanket trailhead. At just over 4,000 feet in elevation, the corner marker is located in a lush old-growth forest. The trail straddles the park boundary for its first mile and a quarter, generally staying above Red Blanket Creek but occasionally beckoning the walker to explore small tributary drainages on the canyon’s north side. The most prominent stream drains the southwest slope of Union Peak, which is an unseen promontory from the canyon floor.

Karl J. Belser in Blue Interval, Ernest G. Moll, Metropolitan Press, Portland, 1935.

In its second mile, the Red Blanket trail veers away from the park and hugs a side of the creek as the canyon narrows. Red Blanket Falls is one of the most spectacular places in the Sky Lakes Wilderness, an area adjacent to the park and is under national forest administration. At an elevation of about 5,000 feet, the falls are the head of Red Blanket Canyon. The transition to a subalpine forest where prolonged snow conditions are the rule is apparent once out of the canyon. As hikers continue along the trail toward Stuart Falls and the park boundary, trees are more often twisted into the pronounced L-shape so common along the Cascade Divide.

There are fewer resident plant and animal species at the higher elevations, largely because of the approximately one degree celsius decrease in average annual temperature for every thousand feet gained in elevation. Yet a hiker will more often obtain sweeping views of the surrounding area. Bald Top is one of the points in the park from where the entirety of Red Blanket Canyon can be seen. Little known even among park rangers, Bald Top is a product of the once active Union Peak volcano. That volcano preceded Mazama and its glaciers carved Red Blanket Canyon, as evidenced by the distinctive U-shape. The other canyons in the park are more recent and bear the mark of Mount Mazama’s climactic eruption to a far more obvious degree. Nevertheless, they also play a important role in perpetuating the biodiversity of the greater Mount Mazama ecosystem.

Saving Bull Trout in Sun Creek

Bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus) and dolly varden (Salvelinus malma) were once considered to be the same species. They have been separated because of genetic, morphological, and behavioral differences. In general, bull trout are the “inland” form, while dolly varden migrate to the ocean (where they spend much of their adult life) and return to reproduce in freshwater. This makes the dolly varden an anadromous fish, similar in behavior to salmon.

Once found in most major river systems in the Pacific Northwest, bull trout distribution has been significantly reduced over the past 30 years and many local extinctions have occurred. Oregon’s Klamath River Basin represents the southern Limit of present day bull trout distribution. The Klamath populations are genetically distinct from other populations in the region and are now restricted to cold headwater streams. Habitat degradation and introduction of non-native fish species are believed to be the primary causes for the decline. Bull trout have been Listed as a Category 2 Species (candidate species under the Endangered Species Act of 1973) by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and is listed as a sensitive species by the State of Oregon.

Bull trout were probably the only fish species present in Sun Creek, a high elevation, second order stream, prior to early introductions of non-native salmonids. National Park Service (NPS) and Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) records indicate repeated stocking of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) in Sun Creek between 1928 and 1971. The only park-wide stream survey conducted during this period took place in 1947. A seasonal naturalist named Orthello Wallis (who later became the first aquatic biologist ever employed by the NPS) found bull trout, rainbow trout, and brook trout in Sun Creek.

A resurvey of Sun Creek was made in the summer of 1989 to investigate the distribution and abundance of fish relative to habitat characteristics. The survey was funded as part of Klamath River Basin water rights adjudication. Sun Creek was surveyed from its headwaters to the park boundary. Bull trout, brook trout, and hybrids from the two species were collected. No rainbow trout were collected in the portion of Sun Creek within the park and may no longer exist in the stream.

Investigators observed that habitat utilization by bull trout and brook trout was very similar. Competition and hybridization with brook trout have probably reduced the distribution of bull trout in Sun Creek. Bull trout were restricted to a 1.9 km reach of the stream and the total number of adult bull trout was estimated at 130 fish. Such a low population density is alarming, since it suggests that local extinction could occur within the next few years.

The NPS is developing a bull trout management program whose goals are to remove brook trout from Sun Creek, build a barrier to prevent re-invasion, and to re-establish a self-sustaining population of bull trout in Sun Creek within Crater Lake National Park. During 1991, park staff convened a “Bull Trout Recovery Team” to develop recommendations on how to best achieve these goals. It consisted of representatives from the NPS, USFWS, ODFW, U.S. Forest Service, California Department of Fish and Game, and Oregon State University. A final report from the group is expected in early 1992 and will form the basis for the first active fish management project ever undertaken in the park. An environmental assessment will be available for public comment before any management action is taken.

Visitors should note that fishing for bull trout in Crater Lake National Park and throughout south central Oregon is prohibited by state law. Bull trout within the park are also protected by federal regulations. Fishing for other species in most park streams is permitted. Copies of fishing regulations are available at the park’s visitor centers. Fishing in Crater Lake for kokanee salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) is allowed. No state license is required and fishing on the lake has been good in recent years.

Mammals of the Pumice Desert

By Ruth Monical and Stephen P. Cross

Much of the Crater Lake National Park is covered in forest. One visible exception is the Pumice Desert on the road to the park’s north entrance. At first glance this 5 1/2 mile square, nearly flat opening appears to be quite barren except for a few scattered lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta). A closer look reveals that many forms of life, including several mammals, use this landscape as a habitat.

At a mean elevation of 5,960 feet, the Pumice Desert is in the Klamath River drainage basin. Yet it is but two miles from the Umpqua River and Rogue River tributaries. Elizabeth Mueller Horn studied the ecology of the Pumice Desert and described the vegetation, which largely consists of herbaceous plants with very sparsely scattered lodgepole pine. She found only 14 plant species with total cover of 4.6 percent. All plants except the lodgepole pine are small herbaceous or woody stemmed forms with various adaptations for surviving in the absence of summer surface moisture and relatively high temperature. The poorly developed soil is relatively porous and deficient in several minerals, a further cause of the depauperate flora. The resulting lack of cover increases daytime summer temperatures, creating a relatively unique park habitat resembling parts of the Great Basin Desert to the east.

Interestingly enough, several animals are adapted for living in the Pumice Desert’s rather harsh micro-habitat. Mammals are an excellent example of the way in which some animals cope with the conditions of extreme temperatures and seasonally restricted food and water. The mammals that occupy the Pumice Desert are either well adapted for living in these restrictive conditions, or are highly mobile, and use the area on a temporary basis, or are simply passing through during movement to more preferred habitat. Field studies by one of us (Monical) indicate that only three mammal species appear to be permanent residents, far fewer than in other park habitats. The Great Basin pocket mouse (Perognathus parvus) and the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) occur in significant numbers. One summer’s live trapping (168 traps set for ten nights) resulted in the capture of 54 individual pocket mice and 46 deer mice.

The Great Basin pocket mouse, a seed-eating specialist, is common in the high desert habitat of western North America. It carries food in its fur lined cheek pouches for storage in a burrow. The ability to metabolize moisture from its food allows the pocket mouse to survive with no free water This nocturnal species also closes its burrow during the day to help maintain a moist environment. When conditions become too severe, it will estivate in the summer or become inactive during the winter.

The deer mouse is the park’s most ubiquitous species, utilizing many different habitats. A highly omnivorous animal, it is able to survive on a variety of vegetative parts, insects, and has even been known to eat other small mammals. Though mostly nocturnal, the deer mouse at times can be seen just before dark when it begins its search for food. An additional adaptation leading to its continuing survival in harsh conditions is its high reproductive rate.

A third, less abundant, resident is the western pocket gopher (Thomomys mazama). Its mounds are seen on the periphery of the desert near the forest edge, where the texture of the pumice soil is more conducive to its underground habits. Gophers are active in the winter and sometimes fill their above-ground burrows under the snow with soil. After melt, these serpent-shaped ridges are evidence of the previous winter’s activity.

Other captured or observed rodents, considered transients, are the yellowpine chipmunk(Tamias amoenus), golden mantled ground squirrel (Spermophilus lateralis), bushy tailed woodrat (Neotoma cinerea), and porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum). It is also likely that snowshoe hares (Lepus americanus), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), and perhaps elk (Cervus elaphus), occasionally venture into this area of marginal habitat. Some species of bats that roost in the nearby forest use the open areas for foraging. Predators are rare but could include the red fox (Vulpes vulpes), coyote (Cants latrans),ermine (Mustela erminea), and long- tailed weasel (Mustela frenata). The pronghorn antelope (Antilocapra americana), sometimes sighted in the park, is known to use open areas such as the Pumice Desert. This location represents one of the westernmost extremes of the current range for this species, usually a Great Basin inhabitant.

Mammals utilize the Pumice Desert for a variety of reasons, even though the harsh environmental conditions preclude most as residents. The presence of the Great Basin pocket mouse as a permanent inhabitant there creates a unique combination of species for Crater Lake National Park.

L. Howard Crawford, Nature Notes, Vol. VIII, No. 3, September 1935.

Heresies of an Interpreter

The presumed purpose of interpretation in the national parks is to add depth to the scenery. Not visual depth, but the depth of understanding. Interpretation is meant to give visitors a new, more informed context to accompany the scenery; a context which transcends the veil of beauty to expose the interaction of natural and human history within the scenery. Good interpretation leaves the visitor with a better base of knowledge, an enticed sense of curiosity, and an interest in the continuing preservation of the place that has inspired them.

Any discussion about interpretation in the national parks is destined to come across the name of Freeman Tilden. As the “father” of modern interpretation, one of Tilden’s most important points was that interpreters should not make things up to fill gaps in their knowledge. Falsifying information reduces interpretation to mere theatrics, perhaps giving the interpreter an ego boost, but certainly not giving visitors an honest impression of the park.

The difference between factual and fictional interpretation gets muddled with the inclusion of what I call non-facts. These are more misinformation than they are lies. When important information is allowed to go unexamined over a long period of time, it can easily become misinformation in light of subsequent research or other changes in the understanding about park resources.

A prime example of how information has to be reexamined is provided in the article by Ron Mastrogiuseppe and Steve Mark. They point out the difference between radio-carbon dates and calendar years. This is significant because the date of the climactic eruption serves as the watermark for the recent geological past in Oregon and elsewhere. It has been used in the reconstruction of prehistoric environments and to place other geological events within a chronological sequence. Differences between radiocarbon dates and calendar years are important to the interpretation of Mazama’s climactic eruption because the roughly 800 year “correction” puts this event at 7,700 calendar years ago. Previously we had been using the radiocarbon date of 6,845 years and assuming that estimate was equivalent to calendar years.

Correcting misinformation is one aspect of strong communication. It is also evident to me that interpreters need to be strong communicators and involved researchers. The emphasis in the National Park Service over the past three decades, however, has been on the communication side of interpretation. Facts are now merely what the interpreter communicates, not something in which they arc directly involved. This is particularly true for interpreters hired for the summer season because their job is so heavily structured toward communicating information in a variety of settings, leaving little time for research or participation in resource management.

Another reason for the weakened relationship between communication and research is the formal bureaucratic separation of interpretation from resource management within the National Park Service. At Crater Lake, interpretation is its own division while resource management is part of a division that houses law enforcement functions. Most of the scientific research in the park takes place through the auspices of resource management staff who are given little incentive within the structure of their job to frequently update interpreters about what they are doing.

In the interest of updating our knowledge about the park and its resources and keeping it current, I think it is time for a closer relationship between resource management and interpretation. This would allow interpreters to give equal attention to the facts, as well as being better able to effectively communicate them without misinformation. If this strong link is not provided, interpretation will fail to add much depth to the scenery.

L. Howard Crawford, Nature Notes, Vol. IX, No. 1, July 1936.

Other pages in this section