Lake Level Bottoms Out

The lowering in the surface level of Crater Lake recorded during the last few years could be over. A return to a more average winter pattern where snowfall amounts exceed 500 inches has already been realized in 1992-93. This snowpack, and any additional precipitation, should all but stop the decline in lake level observed since 1986.

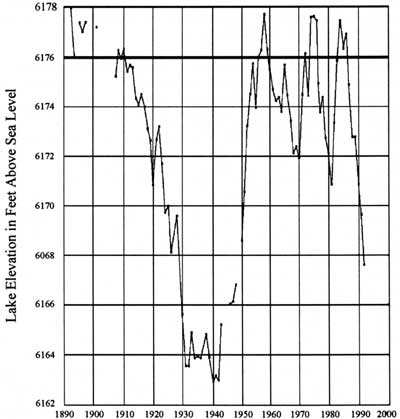

The rise and fall of Crater Lake’s level this century is connected closely to the fluctuations in the region’s weather. Lake levels have been observed and recorded since early this century. Crater Lake was at its deepest in March of 1975 when the lake level measured 6179 feet above mean sea level. This is 16 feet above its lowest point, which was measured in early September of 1942. In 1959, when the U.S. Geological Survey measured the depth of the lake and found it to be 1,932 feet deep, the lake level was 6,176 feet above sea level. This is a good indication that the lake level is always in flux.

Lake level is primarily affected by annual precipitation. For the lake to retain the same level observed the year before, 66 inches of precipitation must be recorded at Park Headquarters. This would come largely as snow and approximates to roughly 530 inches of annual snowfall. If more is received, the lake will be higher during the following summer. If less is recorded, the lake level will fall. A declining lake level has been the case for the last six years. Only 243 inches of snow fell from July 1, 1991 to June 30, 1992. In late September of 1992, at the end of the water year, Crater Lake’s level fell below 6,169 feet. This is close to levels seen in the 1940s and therefore represents a fifty year low. Crater Lake has, however, not been alone among lakes in the region. Upper Klamath Lake and reservoirs throughout southern Oregon also dropped to levels not seen for decades.

If precipitation patterns observed earlier this century are used, Crater Lake will require six years of greater than average snowfall to regain the volume of water lost since 1986. It is likely that the lake will take many more than six years to reach higher levels again. Forecasting future weather patterns and associated lake levels is, at best, risky. Nevertheless, we seem to be at the end of a dry cycle that has been expressed by a drop in Crater Lake’s surface level.

Crater Lake Surface Variation

September 30th

Observed elevation of the lake surface this century. The surface elevation of 6,176 feet is 1,932 feet above the deepest part of the lake. Gaps in the chart are due to periods when measurements were not taken.

Annie Spring Responds to Long-term Drought and Municipal Water Use

Crater Lake National Park has recently experienced one of the most significant droughts in recorded history. The total precipitation of the past three water years is the lowest three-year sum since records began at Park Headquarters in 1931. Surface elevation of the lake itself has cropped from 6,178 feet in 1984 to less than 6,168 feet in 1992.

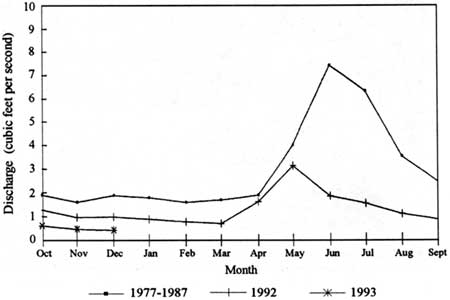

Water for park municipal use is drawn from Annie Spring, the headwaters of Annie Creek. The U.S. Geological Survey has maintained a gauging station on Annie Creek since 1977, shortly after the park moved its water intake facility from Munson Spring to Annie Spring. The gauging station is located directly beneath the road crossing several hundred feet belong Annie Spring. Although the water intake is located at the spring origin, there are no discharge data for this site. The origin is not the creek’s sole source of water, as stream discharge increases several fold between the spring and the road crossing. Nevertheless, discharge data is taken at the gauging station in cfs (cubic feet of water per second) during the water year, which runs from October 1 to September 30.

During the winter of 1993, Annie Creek discharge is expected to drop to its lowest level in the 16 year period for which records have been kept. A typical hydrograph, or flow pattern, for the creek shows flow decreasing through the fall and winter, reaching minimum values in March or April (see chart). Spring flow responds rapidly to snow melt increasing in April or May and peaking in June. Estimated flow values for December 1992 (.43 cfs) are 23% of the 1977-1987 mean for December (1.9 cfs). Discharge values for 1977 through 1991 are adjusted to include water withdrawal from the spring. Values for 1992 and 1993 represent gauge recordings plus estimated water withdrawal rates based on preliminary data analysis.

Although discharge is currently low, this is not the first time low flows have been recorded. Minimum gauge values of .41 cfs end .39 cfs were recorded on March 18, 1989, and April 29,1991, respectively. No water intake problems were noted during 1989 and 1991. Municipal water withdrawal has increased from approximately nine million gallons in 1990 to over 13 million gallons in 1992, compounding trends in reduced spring discharge. Water use increased in each of the three developed areas that withdraw water from Annie Spring (Munson Valley, Rim Village, and Mazama Village). There were no dramatic increases in water use in Munson Valley, Rim Village and Mazama Village during fall and winter 1990-1992. Mazama Village was open, however, for the first time during the months of November and December in 1992. The most dramatic seasonal increases in water use occurred in Mazama Village and Munson Valley in June, July, and August. Water use increased in Mazama Village from approximately 500,000 gallons in July, 1990, to 1,100,000 gallons in July, 1992. In Munson Valley water use increased from approximately 370,000 gallons in August 1990, to 990,000 gallons in August 1992. There is a trend toward increased water use during the winter months. This trend is expected to continue during the winter of 1993 (without water conservation) as Sleepy Hollow housing area at Park Headquarters is near full occupancy.

Accumulated snow fall as of January 12,1993, was above the long-term average for that date. If snow fall trends continue, Annie Spring will recharge and attain average or higher flow rates corresponding closely in time with snow melt. The timing of snow melt, however, can only be approximated

In summary, during the winter of 1993, Annie Spring will likely reach the lowest recorded discharge values since the gauge was installed in 1977. Compounding this problem is increased municipal water use and water withdrawal from the spring. The creek appears to have adequate flow to meet water demands, though the current catchment and withdrawal system is probably not adequate to capture enough flow if current water use and spring flow trends continue. The design of the water system obviously warrants re-visiting, especially with more park development proposed and increased visitor use projected. In light of this new information, it is advisable to make new projections of future water use to determine if Annie Spring can support water withdrawal projections without violating water right allocations or instream flow requirements for channel processes and stream biota.

Annie Creek

Mean Monthly Discharge (cfs)

By Water Year

Ground Squirrel Activity at Rim Village

Sixty Years of High Density Squirrel Populations

The feeding of ground squirrels by visitors in the Rim Village area probably began before the Crater Lake Lodge was constructed in 1909, at a time when camping was allowed anywhere along the rim. In all probability, this further increased after 1928, when the parking lot and cafeteria at Rim Village were constructed in their present locations and the Crater Wall trail was opened (the latter served as the access to the lake until 1959 and is now closed; its trailhead was along the promenade in front of the cafeteria). By the late 1930s, squirrel populations were high at Rim Village and were mentioned by Kenneth Gordon in his The Natural History and Behavior of the Western Chipmunk and Mantled Ground Squirrel, published in 1943. Obviously impressed with the unusual density of ground squirrels at Rim Village, he wrote “…a peanut concession at one of these points should net a tidy sum…”.

Feeding Ground Squirrels

Visitors and ground squirrels meet at the historic location of the Crater Wall trail.

Dr. Gordon’s impression of the squirrel populations at Rim Village may have been based on research he conducted on golden mantled ground squirrel populations in several campgrounds located in Washington State. He concluded in those studies that a population density of five squirrels per acre was well above the population density found under natural conditions. This can be put into perspective by the figure cited in a 1947 paper by Orthello Wallis titled Mammals of Crater Lake National Park. Wallis wrote “…in 1938, there were 150 squirrels, by actual count of marked specimens, between the lodge and the head of the lake [Crater Wall] trail.” Since most of the squirrels live inside the caldera rim within 200 feet of the promenade, this area of roughly four acres provided habitat for approximately 37 squirrels per acre at that time. This figure is equivalent to a population density over seven times that of what Kenneth Gordon considered as “crowded”.

In 1951, seasonal naturalist Ralph Heustis conducted a ground squirrel study along the promenade between the Crater Wall trail and the lodge. His study area was equivalent to that of 1938. Dr. Huestis captured and marked 79 squirrels, a population density considerably less than that found 13 years earlier. Nevertheless, his count showed a density of almost 20 ground squirrels per acre in the Rim Village area. This is easily four to five times larger then whet Gordon expected under natural conditions. Heustis also stated that the greatest density of ground squirrels in the study area was located at the head of the Crater Wall Trail. He noted that a dozen squirrels could often be found there begging for food.

In 1984, S. Kent Schwarzkopf conducted a study on The Feeding of Golden Mantled Ground Squirrels at Crater Lake National Park. The study site was located at the head to the Crater Wall Trail, probably because this was still the location of the highest squirrel activity in the area. I personally spent time counting squirrels at this same location, a place that present park staff call ” Squirrel Row” due to the obviously pronounced activity of squirrels in this area. Periods of observation varied, but at all times of the day I could easily count eight to twelve squirrels and once counted fifteen. In light of past studies and the observations I made, it is fair conclude that large numbers of squirrels have been present at this site for 60 years at a minimum.

Nocturnal Activity Along the Promenade

Gordon observed that “…Ground Squirrels typically accept as much food as possible from visitors, run a short distance to a location where they dig a hole and bury the contents of their pouches before quickly returning for more handouts”. During my surveys, I have noticed that squirrels at the rim in 1992 were no different than those observed in the late 1930s. Most of the food that is accepted from visitors is taken into the caldera, usually about 50 to 60 feet from the promenade, and buried. These squirrels quickly return for more handouts. Their instinct to gather and store food makes golden mantled ground squirrels surprisingly efficient in cleaning up the handouts given to them along the promenade. On several occasions I looked for food scraps in the vicinity of ” Squirrel Row” at the end of a busy day and found that even the crumbs were absent.

Considering the generous handouts that are provided to these rodents by visitors to the park, it would be interesting to determine how many pounds of food is cached each day by these squirrels. Whatever the amount may be, there is no doubt that a substantial quantity of food is moved from the promenade to shallow storage sites inside the caldera. Although these caches may seem secure to the squirrels, shallow hiding places are hardly safe from the prying noses of nocturnal residents like mice and woodrats. As a result, ground squirrels are unintentional conduits of food for a host of other animals in the Rim Village area. It would not be surprising/hat ground squirrel activity during the day is matched by an equal amount of activity at night by nocturnal animals.

The feeding of ground squirrels probably impacts nocturnal rodents who feed on their food caches. In an attempt to estimate the population density of nocturnal rodents, the soil along the prominade wall was swept (right side of picture) at about 9:00 pm. At 6:00 am the next day, the swept area was heavily trampled by nocturnal rodents (left side of picture). (Note: broom marks in the picture were made at 6:00 am for contrast needed in the photo.)

In an attempt to assess the level of nocturnal activity and the associated population densities of animals in the Rim Village area, I went there one evening around nine and used a broom to gently smooth down the dirt at “Squirrel Row”. At roughly six o’clock the next morning, I returned to see what had happened. The area I swept was heavily trampled by small rodents like mice and wood rats. Deer tracks were also noted as were some tracks of ravens that I scared away when I arrived. The total number of individual rodents that had been active here during the night was not something that I could determine but I could easily say that activity was intense. The level of activity along the promenade was surprising, especially in light of the efficiency with which ground squirrels gather every scrap that they can find and transport it to cache sites inside the caldera. If the nocturnal activity along the promenade was as pronounced as it was with only a few morsels of food available and a poor selection of shelter, I could only imagine what activity must be like 50 to 60 feet below the rim where squirrel caches abounded and shelter is abundant! It seems reasonable to speculate that nocturnal rodent activity must easily match, if not exceed, the activity of the ground squirrels that people feed on days during the summer.

Accumulations of Animal Feces

The high density of rodents in the Rim Village area means that there is also an appreciable amount of rodent excrement being deposited there, too. I trapped several squirrels and collected the feces that was excreted during the active period of their day. All these samples were dried and weighed on a triple beam balance that was accurate to a hundredth of a gram. I found that the average weight of a squirrels daily excrement (excluding urine) was about 1.5 grams (dry weight). Assuming that golden mantled ground squirrels are active for five months out of the year (May to September) and estimating that there are about 20 squirrels per acre in the Rim Village area, then the calculation of 4. 5 kilograms ( 10 pounds) per acre is a reasonable approximation for the accumulation of their body waste over one summer season. This means that over the past 60 years or more of historically high ground squirrel population densities in Rim Village, at least 270 kilograms (600 pounds) of feces per acre has been produced there by ground squirrels alone. Much of this 600 pounds was probably deposited inside the caldera wall. If one adds in the waste products deposited by enhanced populations of birds, mice, rats and deer that feed on squirrel caches and if this includes the waste deposits contributed by an assortment of predators that feed on the dense populations of rodents, the total fecal deposit in the Rim Village area over the past 60 years is probably close to or more than 900 kilograms (one ton) per acre.

Other pages in this section