Volume 24, 1993

All material courtesy of the National Park Service. These publications can also be found at http://npshistory.com/

Nature Notes is produced by the National Park Service. © 1993

Introduction

By Kent J. Taylor, Chief of Interpretation

Last year’s volume of Nature Notes from Crater Lake marked the first appearance of this publication in more than 30 years. The Crater Lake Natural History Association decided there was sufficient visitor interest for a 1993 edition because the limited number of copies in 1992 sold quickly. Contributors responded enthusiastically, so this volume is larger than last year’s effort.

Nature Notes share a common characteristic of being original research or observation relevant to the visitor experience at Crater Lake National Park. In most cases these articles have not been published previously. All of the authors are employees of the National Park Service, but their contributions were made primarily on a volunteer basis. Reprinting Nature Notes articles is encouraged, as long as credit is given to the authors and the Crater Lake Natural History Association.

This volume begins with an article on the park’s 1992 northern spotted owl survey. The results changed the way Crater Lake National Park has been viewed relative to the habitat it provides for the bird. Lori Stonum’s piece and the others that follow it serve to underscore the point made in last year’s lead article that Crater Lake National Park continues to be a vibrant field for scientific research.

The Crater Lake Natural History Association was established in 1942. Its purpose is to aid the National Park Service in educational, scientific, cultural, historical, and interpretive programs. Toward this end it sponsors this volume of Nature Notes from Crater Lake. The association operates three publication sales outlets, two at Crater Lake National Park and one at the Illinois Valley Visitor Center in Cave Junction, Oregon. Proceeds from sales items are used entirely to support the association’s goals. A list of items for sale can be obtained by writing to the Business Manager, Crater Lake Natural History Association, P.O. Box 157, Crater Lake OR 97604, or by calling (541)594-2211 ext. 499.

Spotted Owl Survey

By Lori Stonum

The northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina) is one of three subspecies of spotted owls. It is a medium-sized forest owl distinguished by its large brown eyes and mottled brown and white breast. The spotted owl is a monogamous, long-lived species, that is mostly nocturnal. Ranging from southern British Columbia to northern California, it is found on the east and west slopes of the Cascade Range and on the Olympic Peninsula. Spotted owls live mostly in low elevation coniferous old growth forests and have a limited seasonal migration.

The first recorded observation of a spotted owl at Crater Lake National Park was in 1934. Between 1934 and 1978, there were several other sightings reported. The first surveys of the spotted owl at the park were conducted in 1978 in cooperation with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and the U.S. Forest Service. Sporadic studies have been conducted since then, but a complete census was never conducted. Until 1986, studies within the park concentrated on the west side of the Cascade Range. When the surveying resumed in 1990, the southern portion of the park was included. The 1990 and 1991 surveys, however, consisted only of two-day projects with limited coverage of the park’s spotted owl habitat.

A more comprehensive survey of the northern spotted owl at Crater Lake National Park commenced in May 1992. This was the first year that a study of spotted owls in the park was conducted according to standard protocol. Survey sites were determined based on historic spotted owl sites, areas of good habitat, and the location of proposed construction within the park. Since the survey was started late in the season compared to others in the region, we concentrated on historic owl sites and future construction zones, making them our priority. New sites were added as time became available.

Overall, the number of owls found at Crater Lake in 1992 was unexpected. We now know that the park holds greater significance for spotted owls than previously thought. During the 1990 and 1991 surveys, two pairs and one single male spotted owl were found each year. By the end of the 1992 field season, we had located seven pairs of spotted owls. Six of the seven pairs had two juveniles. Three single owls of unknown reproductive status were also found, making a total of 29 owls found in the park. Of these, 12 owls were banded with the help of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife so that the owls can be identified in future studies.

The 1992 spotted owl survey produced two significant findings. One was the large number of owls located on the east side of the Cascade Range. Four pairs of spotted owls found in the park this year were on the east side of the Cascades, which was somewhat unexpected when considering that most spotted owls are found west of the mountains. The second finding was the relatively high elevation at which several owl pairs were living. For two years in a row, Crater Lake National Park has held the state record for the highest elevation at which a spotted owl pair was found. The Annie Creek site was the 1991 state record at 1829 meters (6000 ft.), and in 1992 it was the Crater Peak site at 1996 meters (6550 feet). In future studies we hope to be able to focus on these east side and high elevation sites to determine if there are factors influencing the owl’s range and reproductive status, as compared to west side and lower elevation sites.

There is still a lot of work to be done in the park on spotted owls. Less than 30 percent of the 50,000 acres of spotted owl habitat existing within Crater Lake National Park was surveyed. Considering the exciting results of the 1992 survey, the potential for even greater numbers of owls existing within the park is very high. If the spotted owl program at Crater Lake can continue to expand and survey more of the suitable habitat, perhaps the complete status of the spotted owls at Crater Lake could be better known.

Native Species Protection and Exotic Species Control: A Bull Trout Restoration Project in Sun Creek

By Mark Buktenica

Bull trout (Salvinus confluentus), and dolly varden (Salvelinus malma), were once considered to be the same species. They are now considered to be distinct species based on genetic, morphological and behavioral differences. In general, bull trout are an inland, freshwater form, whereas dolly varden spend much of their adult life history in the ocean before returning to freshwater to reproduce.

Although bull trout were once found in most major river systems in the Pacific Northwest and Canada, their distribution has been significantly reduced over the past 30 years, and many populations have become extinct. Habitat degradation and introduction of non-native and exotic fish species are believed to be the primary causes for the recent decline. The Klamath River Basin in Oregon is the southern limit of bull trout populations today. These populations are genetically distinct from other Pacific Northwest bull trout populations and qualify as a separate species for consideration under the Endangered Species Act. Bull trout are currently listed as a category 2 species (candidate species under the Endangered Species Act) by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The American Fisheries Society has petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list the Klamath River Basin bull trout as an endangered species.

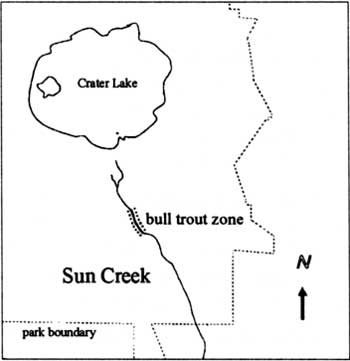

A 1947 stream survey in the park’s Sun Creek drainage indicated that bull trout were well distributed in the headwater stream along with brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis)that were stocked into the stream in the early pert of this century. A survey of the fish populations and instream habitat in Sun Creek in the summer of 1989 revealed that the bull trout population was reduced to 130 adult fish and restricted to a 1.9 km (1.2 mi) section of the stream (see map). Brook trout were distributed throughout the stream. Hybridization and competition with the introduced brook trout appeared to threaten the bull trout population with a high risk of extinction.

This alarming information led the park to draft a bull trout restoration plan in 1990. The objectives of the plan were to restore the remnant population of bull trout to historic numbers and distribution in Sun Creek, remove the introduced brook trout, and prevent the re-invasion of non-native species from waters outside of the park in the future. The plan called for additional research in 1990 and 1991 to verify the distribution and abundance of the bull trout, evaluate stream chemistry, temperature, flow, retention and travel time, and conduct surveys of amphibians and aquatic insects, with an emphasis on looking for rare, threatened and endangered taxa. Laboratory tests were conducted to determine the specific toxicity of the fish toxin Antimycin on trout in Sun Creek water. Alternative locations for a “back-up” population of bull trout were evaluated, including hatcheries and isolated creeks within Crater Lake National Park. Also evaluated were alternative methods for fish removal.

In October 1991, a peer panel and recovery team was assembled to evaluate the research to date and the recovery plan, as well as to offer recommendations on implementation of the plan. The peer panel included personnel from the National Park Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Service, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Oregon State University, and the Desert Fishes Council. Panel members had expertise in fish population restoration, fish toxins, electrofishing, fish barriers, genetics and fish and macroinvertebrate ecology.

The long-term goal of the plan was to eradicate brook bout from Sun Creek within the boundary of Crater Lake National Park. An immediate objective was to remove as many brook trout as possible from the portion of Sun Creek within the park. This would allow bull trout to increase in number and disperse downstream. The loss of any bull trout during the removal process was not an acceptable risk, as the viability of such a small population was already in question.

During the summer of 1992, a restoration program was initiated. Two log and rock fish migration barriers were constructed in Sun Creek near the park boundary to prevent the re-invasion of non-native fishes. The structures created an elevated stream channel and an artificial waterfall in a naturally constricted section of the stream. If the downstream barrier were to fail, the upstream barrier would prevent brook trout from immigrating further upstream into the park before the lower barrier could be repaired.

Brook trout were removed from Sun Creek with non-lethal electroshockers upstream of the bull trout population. Starting at the headwaters of Sun Creek, fifty meter sections of stream were blocked off with nets. Each section was electrofished until no fish were captured two out of three passes up the stream. This process was repeated two more times during the summer. Data were collected on fish weight, length, sex, abundance, biomass, and distribution.

Recent literature suggested that electroshocking may have higher injury and mortality rates on fish than previously believed. Therefore, electroshocking for brook trout in the bull trout section of the stream was tried with caution in 1992 and abandoned when the bull trout showed signs of stress. Alternative methods for removal of the brook trout in the bull trout section are now being evaluated. A special study was conducted in the fall of 1992 to evaluate rates of injury to brook trout from three different types of electroshockers. The data have not been evaluated at this time.

Non-lethal samples of fin tissue were removed from brook trout, bull trout, and brook trout-bull trout hybrids in 1992. These samples will be used for genetic analyses to evaluate hybridization and to compare the genetic make-up of Sun Creek bull trout with other populations located in the Klamath and Columbia basins. Results of the study are not yet available.

The recovery team agreed that electroshocking techniques would not be effective in fish removal downstream of the bull trout owing to increased stream flow and structural complexity of the stream channel. Therefore, brook trout were removed with Antimycin. This is an antibiotic that is extremely toxic to fish at dosages as low as 4 parts per billion. Antimycin is not toxic to mammals and birds, but is toxic to amphibians and to many species of aquatic insects. The Antimycin was successfully neutralized below the lower barrier and upstream of the boundary with potassium permanginate. Brook trout were collected at block net stations and by “dip-netters” along the stream. No amphibians were collected and preliminary observations suggested that insect mortality was low.

A sampling program will be initiated in 1993, supported by funding made available through the National Park Service. The objectives of the program are to monitor the recovery of insect and bull trout populations and to continue the removal of non-native brook trout.

Bull trout distribution in Sun Creek, Crater Lake National Park, Oregon

Peregrine Falcons Soar Over Crater Lake

Falco peregrinus

Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) are crow-sized falcons that are distributed throughout the world. Their diet consists of other birds. Chemicals such as Dichloro Diphenyl Trichloroethane (DDT) tend to accumulate in their system because the peregrine is at the top of the food chain.

DDT, which was banned in the United States in 1972, has caused thinning of egg shells and dehydration. The chemical continues to be a problem because the pesticide is still being used in Mexico and South America, where many peregrines or their food sources migrate.

DDT, which was banned in the United States in 1972, has caused thinning of egg shells and dehydration. The chemical continues to be a problem because the pesticide is still being used in Mexico and South America, where many peregrines or their food sources migrate.

The only known active peregrine eyrie in Oregon in recent years was at Crater Lake National Park. It was discovered in 1979, and remained active until 1983, when both adult birds disappeared. Although the birds in the eyrie successfully fledged young in 1979, they were unsuccessful in 1980. Each of the three eggs laid the second year showed high levels of a derivative of DDT. As a result, young peregrines were fostered into the nest in 1981 and 1982.

When both adult peregrines disappeared in 1983, a method of releasing birds into the wild known as hacking was initiated. Twelve young were hacked over the next four years. Roaming peregrines were seen at the hack site in all four years, and non-breeding peregrines were seen in other areas around Crater Lake. An active pair was present at the historic eyrie in 1986, but successful breeding did not take place.

Nesting again took place at Crater Lake in 1987. The nest was manipulated to ensure that the pair would successfully fledge young. Four eggs were removed from the nest, three of which hatched and were fledged in California. Two captive-bred young were fostered into the Crater Lake eyrie. Unfortunately, one of the young was killed by a great horned owl (Bubo virginianus Gmelin). The other bird successfully fledged.

The peregrines again used the historic eyrie in 1988. They laid four eggs, of which three hatched. Approximately twelve days later all of the young and the adult female were killed by a great horned owl. In order to ensure fledging of peregrines in the Crater Lake area it was decided to cross-foster young peregrines into a nearby prairie falcon nest. This effort was successful in fledging two peregrines that year.

It is believed that the male returned with an immature female in 1989 and 1990, but monitoring during those years was limited. In 1991 the historic eyrie was again active. An adult peregrine pair was successful in fledging three young without any manipulation. Of interest was the male of the pair being identified as a released bird due to the band on its leg. The spring and summer of 1992 was also a successful breeding season for the falcons. Two eggs were produced in the eyrie with both young subsequently being fledged.

The successful fledging of young peregrines during the past two years is very promising and is the result of much effort and patience. The site will again be monitored during 1993. Should the falcons continue to nest at the same eyrie, steps may need to be taken to monitor great horned owls in the area and to evaluate the effects of predation on the peregrines. Although the hatching success in recent years has been good, analysis of the eggs shows significant thinning and that the female was subjected to pesticide contamination.

Air Quality at Crater Lake

Most people visiting Crater Lake find themselves in awe of the beautiful blue water. When they gasp at the beauty, they should also realize that they are breathing some of the cleanest air in the world.

The air is so pure at Crater Lake that on the clearest day you can see at least 190 miles, and occasionally to the 240 mile limit. Actual day to day visibility at Crater Lake averages about 105 miles.

There are some threats, however, to Crater Lake’s air quality. Klamath Falls and Medford, each about 55 air miles from Crater Lake, are non-attainment areas in the state; this means that these cities do not comply with Oregon’s goals for air quality in populated areas. Nevertheless, the small amount of pollution we do have is not directly associated with an urban or industrial corridor. Weather patterns in those areas usually trap the pollutants to the ground. At Crater Lake, air movement is generally characterized by westerly winds associated with the presence of weather systems formed over the Pacific Ocean. Air pollution over the park is usually particulate from slash burning, wildfires, and agricultural burning.

One big reason efforts are being made to protect our air is that preserving scenic vistas is a boon to tourism. Although fire danger is a compelling reason to prohibit slash burning during the summer months, land managers want to keep visibility at its best during the tourist season. Oregon hosts 11.8 million visitors every year who spend over $1.4 billion in the state. Roughly $17.4 million of that total is spent to visit the state’s wilderness areas, including Crater Lake National Park.

The National Park Service and the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality monitor the air at Crater Lake in four different ways:

Standard Visual Range (SVR) data is collected by a 35mm camera which photographs a vista of known distance three times a day. Calculations are made of how far past, or in front of a known target the horizon can be seen in the photograph. Estimates of how many particles are in the air are made by calculating how well the target contrasts with the area in front of it and behind it. There are three SVR cameras in the park. One is located on Dutton Cliff and another is on Watchman; both are aimed at Yamsay Mountain to the east of the park. A third camera is at Rim Village, where it can view Mount Theilson to the north of Crater Lake.

The Transmissometer has a transmitting station at Rim Village that sends a light beam across the lake to a receiving station at Wineglass on the northeast side of the lake. By calculating how much light is sent and how much is received, the amount lost traveling from one site to another can be determined. The light is scattered by particles in the air, so the more light received, the cleaner the air.

The Nephelometer is an instrument that takes air into a vacuum tube and sends light through the sample. It then measures the intensity of light that is scattered by particles contained within the instrument’s optical path. The less the light is scattered the cleaner the air. The park’s Nephelometer is located at Rim Village.

Finally, the Improve pulls air through many different filters. Each filter is a different degree or size, meaning each filter will catch a different sized particle. To see what particles are in the air, each filter is chemically analyzed. This device is located at Park Headquarters.

Through use of this technology and other indicators, we know that the air quality over Crater Lake has been impacted by human activities. Presently, naked eye visibility at Crater Lake National Park is substantially impaired for 4.6 percent of all daylight hours. Nevertheless, this figure is impressive when compared with stations further north in Oregon. Crater Lake is, in fact, often the standard used when judging air quality in other areas. By contrast, Mount Hood’s visibility is impaired 21 percent of the time, while Mount Washington’s figure is 42 percent and Portland’s is 85 percent.

Although a 4.6 percent impairment index may seem satisfactory when compared to other areas, this may rise to five, ten, or even 20 percent without the cooperation of people. We all have a responsibility to ensure clean air–our next breath depends on it.

Where Have the Whitebark Pines Gone?

Even a cursory glance at the landscape reveals that vegetation is not distributed at random, but occurs in mosaics as an expression of several interacting variables. The whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis, meaning white-stemmed pine) is a tree found at Crater Lake National Park generally above 6500 feet on exposed slopes in dry, rocky soils. This tree is easily identified by its whitish-gray bark and often twisted branches. Although Crater Lake National Park has no true timberline, whitebark pine forms the elfinwood or krummholz of timberline in many western mountain ranges.

Whitebark pine is a pioneer species colonizing subalpine habitats as the first tree. An amazing example of its pioneering ability can be seen at the Newberry caldera where whitebark pine is the only tree established upon the relatively recent obsidian surface; even the nearby lodgepole pines (P. contorta, subsp. murrayana) abruptly end near the toe of the flow. At the Crater Lake caldera, whitebark pine may have been the first tree to colonize the pumice slopes of old Mount Mazama within the first century following the climactic eruption. Whitebark pine is generally encountered as a pioneer tree, as there are several places around the caldera rim where old mother trees provided a favorable microclimate for the establishment beneath their canopy of subalpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa) or mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana). Whitebark pine is arranged in ribbons or bands along the contours of Cloudcap and other habitats along the caldera’s edge. These sites represent slightly higher, rocky substrate for the survival of whitebark seedlings since exposed areas devoid of snow earlier in the year have a significantly longer growing season.

Most pine seeds have wings for wind dispersal, but whitebark seeds have retained only a rudimentary wing. The dispersal agent has become the Clark’s Nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana). These birds have learned to retrieve whitebark seeds with their specialized beaks, storinga number in their sublingual pouch, and methodically storing seeds in soil caches. Only a fraction of the seed caches are retrieved, however, so some caches sprout seedlings in clumps which may grow into larger whitebark pine colonies.

Whitebark pine appears to be sensitive to a certain set of environmental conditions. Although it is often viewed only as an indicator of a short “rowing season and cold temperatures, this species occupies a niche in the subalpine forest that is far from simple. The tree can be found in relatively pure stands or in association with lodgepole pine and western white pine (P. monticola). The distribution of related species like limber pine (P.flexilis), bristlecone pine (P. longaeva), and foxtail pine (P. balfouriana)somewhat overlap that of the whitebark and can occupy what would often seem to be the latter’s place forming the edge of timberline. Whitebark pine’s distribution poses some nagging questions to dendrologists. For example, it provides the name for Nevada’s Pine Forest Range but mysteriously remains absent in similar subalpine habitats on Steens Mountain in southeastern Oregon, only several air miles to the north. In southern Oregon, the whitebark pine may have disappeared on Mount Ashland in recent times and is presently almost gone from the top of Crater Lake’s Wizard Island.

One of the reasons that whitebark and other pines are often so puzzling is that species of Pinus display much variation as well as many similarities. For example, whitebark pine and limber pine (the rarest native coniferous species in Oregon, but more common in the Great Basin and northern Rockies) mimic each other in many characters. Similarly, the ponderosa pine (P.) found along Annie and Sun creeks, for instance, display a strong Washoe pine (P. washoensis) element. This is thought to be a high elevation variant of the ponderosa’s northwestern distribution and may account for its presence at higher elevations inside the caldera. Genetic variability in the park’s whitebark pine may not be as great as in the ponderosa forests, but the loss of a population as small as the one on Wizard Island may imperil a distinct local seed source.

What is disturbing about the whitebark pine of Wizard Island is their seemingly rapid decline. Photographs taken at various times through the 1960s show living trees on top of the island. By July 1991, however, the authors could find only one living specimen. This small population’s relatively sudden nosedive may be due to one or several causes. Might it be human activity, air pollution, drought, mountain pine beetle, or blister rust infection? The whitebark’s decline is more likely tied to a combination of these factors, which makes the testing of single hypotheses (a key to the application of scientific method to the problem) very difficult or, at best, inconclusive.

Efforts aimed at monitoring environmental change in national parks like Crater Lake are generally handicapped by the lack of critical baseline information. Material available to the historian may help to reconstruct past conditions, but investigators should be aware of their possible shortcomings. The documentary record is limited to the historic period, whether it is in the form of photographs or writings.

Repeat photography is constrained by the scale and resolution of the original photo, as well as by the identifiable background features that allow a view to be replicated. Observations about the condition of flora throughout the park are usually fragmentary. Some describe what would seem to be unlikely events, even though the journalist may otherwise be credible. One example is a newspaper article of 1903 where Klamath Falls hotelier and photographer Maud Baldwin noted that Wizard Island was ‘”alive with grasshoppers. ” Sufficient detail or locality data to verify an observation can be a problem, too. Much effort was expended by Crater Lake’s chief park naturalist in the 1960s trying to track clown a colleague’s discovery of the prostrate juniper (Juniperus communis) specimen probably living near the Watchman in 1929.

Other changes that might have occurred during the historic period lack any form of documentation. Just one of many examples in the park is the poor condition of Sun Meadow’s vegetation when compared to the floral mosaic of Sun Notch. Simplistic explanations, such as sheep grazing prior to the park’s establishment or a poor soil nutrient budget, are often offered by park staff when the limitations of available evidence or funding seem to frustrate efforts to study the situation further.

What the whitebark’s disappearance on Wizard Island may illustrate, as have the attempts to understand fluctuations in Crater Lake’s clarity, is that we really under stand very little about the park’s ecosystems. Certainly more research is essential, but the limitations of available data have to be accepted since causation may be due to a number of factors not easily separable into testable hypotheses. Instead of certainty, all history and science can yield is a prediction of possibilities if the limitations affecting available evidence can be overcome through sound methodology.

Explanations based on models of complexity rather than simplicity will have to be complemented, however, by a willingness to admit that sometimes we do not have all the answers. Since whitebark pine ring the summit crater which provides the lake’s name, what better symbol of uncertainty could there be for a phenomenon as complex as Crater Lake?

Drought and the 1992 Pond Survey

Introduction

The summer of 1992 arrived with a combination of circumstances that may earmark this season as having the most extreme drought conditions ever recorded in the history of Crater Lake National Park. Two factors were instrumental in making this happen. First, Crater Lake National Park experienced a very dry winter and spring from December 1991 to May 1992, with snowfall for that period being 45 percent of the average amount. This has a historic significance because it marks the lowest accumulations of snowfall in the 60 year weather record of Crater Lake National Park. Second, the summer of 1992 marks the sixth consecutive year of drought in this region, though below average precipitation has been the rule for all but three years in the past fifteen. Inasmuch as the park’s surface water resources were already under stress, the record low snowfall of this winter and spring intensified the scenario.

Six Ponds That Survived the Drought

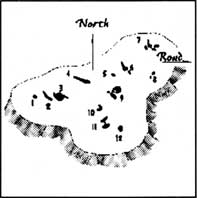

Twenty eight ponds are located inside the boundaries of Crater Lake National Park, with most situated in the western half of the park. The majority of these ponds have depths of two to four feet when filled with water and have maximum diameters ranging from 30 to 200 feet. Spruce Lake is the largest of the ponds, with a maximum depth of about 12 feet end a length of over 300 feet. Several ponds in the Sphagnum Bog area and on Whitehorse Bluff have maximum depths of six to eight inches and diameters of 20 to 50 feet. All of the ponds appear to be filled only by direct rain or snowfall rather than by surface water. Some subsurface inflow is a possibility in a couple of ponds. The ability of these ponds to sustain appreciable water levels through the dry summer seems to be governed by the substrate that forms the basins where these ponds are located. Ponds which are poised in depressions on the surface of lava flows, like Quillwort Pond and Whitehorse Pond #3, for example, are the most persistent, whereas ponds poised in pumice fields from Mount Mazama’s climactic eruption, like Spruce Lake and Lake West, are the least persistent.

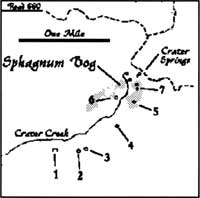

During the summer of 1992, it is likely that only six of the twenty eight ponds in Crater Lake National Park did not dry up before the first substantial storms came in mid October. These ponds are listed in the table and can be found on the I :62,500 topographic map of the park published by the U. S. Geological Survey. The figures delineate the locations of ponds in the Sphagnum Bog and Whitehorse Bluff areas.

| NAME/LOCATION OF POND |

DATE OF SURVEY |

WATER DEPTH |

NOTES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sphagnum Bog #2 | 9 Aug 1992 | 1 ft. | May have received subsurface water from Sphagnum Bog Pond #3 |

| South of Castle Point | 25 Aug 1992 | 8-10 in. | Large salamander population |

| Whitehorse #2 | 2 Sept 1992 | 1 ft. | May be receiving subsurface water from Whitehorse Pond #3 |

| Whitehorse #3 | 2 Sept 1992 | 2+ ft. | Possibly the most robust pond in the park |

| Quillwort Pond | 24 Aug 1992 | 2 ft. | Water level was about the same when observed by others in mid-October |

| North of Pumice Flat | 10 Aug 1992 | 2+ ft. | Heavily used by elk |

Most persistent ponds of Crater Lake National Park. (see maps for the numbering system used with ponds in the Sphagnum Bog area and on the Whitehorse Bluff.)

Sphagnum Bog ponds |

Whitehorse Bluff ponds |

Other pages in this section