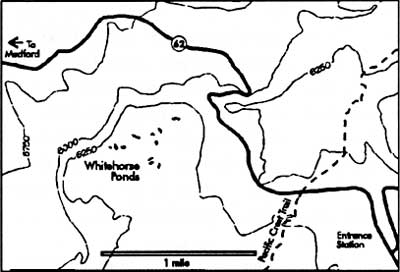

Whitehorse Ponds: A Special Aquatic Study

A short hike from the junction of the Pacific Crest Trail and Highway 62 can take you to the top of Whitehorse Bluff. It can be reached by a relatively easy crosscountry walk and a short climb. The top of the bluff is at 6,200 feet in elevation and a world apart from surrounding areas below it. Hiking across the bluff will also lead you to encounter the setting of forest ponds. Atop Whitehorse Bluff are sixteen ponds, each with its unique inhabitants. During the summer of 1993, I along with David Hartlesveldt and Robert Truitt, received funding from the Crater Lake Natural History Association to survey Whitehorse Ponds. This survey included the biotic, physical, and chemical nature of these ponds.

A reconnaissance of the park’s forest ponds by Roger Brandt in 1992 (see pp. 12-13 of the 1993 Nature Notes from Crater Lake) served as the precursor to this survey. In visiting the Whitehorse Ponds five times in 1993, our investigation gathered data on the phytoplankton, zooplankton, vascular plants, water chemistry, and other pond inhabitants. Samples were collected with zooplankton nets, Van Dorn water samplers, and special nutrient bottles for chemical analyses. Instruments were deployed to measure in situ temperatures, pH, and conductivity. We also analyzed samples for plankton and chemical concentrations.

The authors made their first visit to the ponds on July 14,1993, when they found the area to be teeming with life. The drone of mosquitoes filled the air, while snow melted directly into the ponds. Even with the wet winter season and all the snow, the ponds were about 30 cm below capacity. This may suggest that water levels had not fully recovered from several prior years of dry weather.

Even so, the ponds were found to support healthy populations of dragon flies, water striders and other aquatic insects, frogs, toads, salamanders, moss and other aquatic plants, as well as many types of plankton.

Part of the survey involved comparing the ponds with the waters of Crater Lake, the springs which enter the lake from inside the caldera, and precipitation such as rain and snow. As a result, we found the amount of phosphorus, sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and chloride ion concentrations in these ponds to be similar to precipitation, but very different from the lake and springs.

We also discovered that levels of two nutrients, sulfate and nitrate, in the ponds were far below levels in precipitation and in lake water. This suggests that vascular plants and phytoplankton in the ponds are quickly assimilating these nutrients as they become available from snow melt, rainfall, or through seepage from ground water. Crater Lake has been documented to be nitrate limited, meaning that the lack of nitrate is probably a key factor in limiting plant growth. The relative scarcity of nitrate ions in the ponds may similarly retard plant growth in these habitats.

Other chemical tests conducted include dissolved oxygen, pH, conductivity, and alkalinity. These estimate oxygen concentration, the acid/base level, total salt content, and the ability of water to neutralize acids, respectively. Conductivity data suggest these ponds are mostly rainwater supported with a few added ions from the soil. Alkalinity measurements reinforce the contention that the lake is fed by waters other than just rain or surface snowmelt. Measurements of alkalinity also show that the ponds have little ability to buffer additions of acid. This means that the ponds will most likely be affected if acid rain enters the pond complex.

Since the ponds appear to be fed solely by direct or indirect precipitation, change in the chemistry of the entering precipitation could likely affect their delicate balance. One threat may be from the burning of fossil fuels, which produces carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur oxides. These gases ultimately become carbonic acid, nitric acid, and sulfuric acid, which when combined with precipitation, can lower the pH of surface waters. This anthropogenic input could be a major agent of change for the ponds and lakes throughout the Cascade Range in the coming years.

The ponds were inhabited by several species of phytoplankton and their concentrations varied depending on the time of year. They include three species of Chrysophyta, two species of Chlorophyta, Cryptophyta, Cyanobacteria, and one species of Euglenophyta and Bacilariophyta. During one August visit, one pond sampled for phytoplankton contained mostly cyanobacteria. In another pond on the same day, more than half the phytoplankton sampled were cysts of a Chrysophyta. On a September visit, one phytoplankton sample contained more than 80 percent of one Chlorophyta species.

Identified zooplankton included eight species of Rotifers (a class of microscopic animals found only in fresh water whose anterior cilia give the appearance of rapidly revolving wheels when in motion) and three species of Cladorcerans (water fleas). There were also two species each of calanoid copepodes and cyclopoid copepodes. These orders often occur together, but usually feed on different material. We also found one fairy shrimp species. This virtually defenseless organism is often discovered in temporary ponds and is rarely present in ponds with carnivorous insects or fish. In terms of numbers, the most dominate zooplankton was Diaphanosoma brachyurum (a cladoceran), while the seed shrimp, Hexarthra mira, was the least abundant.

The ponds had a greater zooplankton diversity in early summer, but a greater number of individuals represented fewer species by fall. This suggests that autumn’s stressful conditions helped select species which take advantage of greater light intensity and higher water temperatures.

In small and remote places are found pockets of life’s communities. The sun, water, and nutrients of the Whitehorse Pond complex create one such niche. Simply walking to one of these ponds to experience helps one to appreciate life on earth because biotic tenacity is so well demonstrated here. By looking under the surface of a pond one finds a web of conditions which allow its inhabitants to survive. Dissolved nutrients support the ponds’ green plants, while algae support the ponds’ small animals.

Whitehorse Bluff presents scientists and visitors alike with a unique opportunity to study and appreciate a little known, but important, resource in Crater Lake National Park. The data collected in 1993 will provide background or baseline information, thereby securing a chemical and biological setting for the ponds in time. Future surveys will be able to compare data, thus allowing for trend analysis. These trends will help provide managers with better information on how to manage the pond, stream, and lake environments in and around Crater Lake National Park.

John Salinas is a former seasonal employee at Crater Lake. He teaches chemistry and physics at Rogue Community College in Grants Pass, Oregon.

A New Pacific Crest Trail at Crater Lake

The Pacific Crest Trail is a 2,400 mile long trail system that traverses some of the most scenic and remote backcountry wilderness in California, Oregon, and Washington. This very popular trail has an interesting saga and includes Crater Lake National Park as one of its prime destinations.

In 1920, the U.S. Forest Service flagged a trail that extended from Mt. Hood to Crater Lake and dubbed it the Oregon Skyline Trail. By 1928 public interest in a high mountain trail modeled after the “Long Trail of the Appalachians” gave rise to a federally supported endeavor. As a result, the Cascade Crest Trail in Washington became linked with the Oregon Skyline Trail in the 1930s. By 1937 the characteristic Pacific Crest Trail diamond-shaped trail markers extended from the Canadian line to the border with Mexico. In parts of California, however, trail construction was sporadic-sometimes forcing hikers to become masters of improvisation as they forded streams without bridges and followed maps that showed footpaths where none existed. Despite these obstacles, the Pacific Crest Trail is now complete and enjoys continuing public support.

An Alternate Route

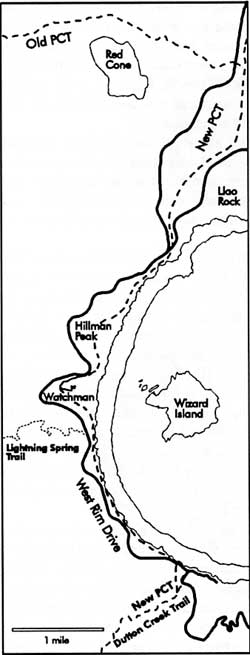

Trail users have found that the PCT affords some of the most ecologically diverse and beautiful vistas in the western United States. Even so, the most ardent supporters have long complained that the trail through Crater Lake National Park is one of the weakest links on this nationally important scenic route. It cuts through miles of lodgepole forests and stays several miles away from the rim of Crater Lake. Consequently, many hikers have by-passed this stretch of the PCT and lost hope of an alternate route being provided. After many years of disappointment, however, those hikers are in for an exciting and pleasant surprise. During the summer of 1994 work parties representing the National Park Service and the Friends of Crater Lake completed an eleven mile alternate route that traverses several ecological zones and affords numerous views of Crater Lake from the caldera rim.

The alternate route utilizes existing trails and an abandoned road bed as well as entirely new stretches of trail. Access to the new route from the existing Pacific Crest Trail is gained in two ways. South of the lake, the PCT reaches a junction point with the Dutton Creek Trail. The latter path is part of the new alternate route and by following it on its northerly and direct path to the rim, immediate access to the caldera and adjoining facilities at Rim Village is possible. If you are traveling the PCT from north of Crater Lake, access to the alternate route can be gained from the trailhead junction just south of the Pumice Desert. The new route travels to the east of the trailhead and skirts along the base of Grouse Hill before climbing to the caldera rim just beyond Llao Rock.

Highlights of the New Route

Map by Susan Marvin. |

One of the most pleasant places to relax and get off your feet is at the Dutton Creek junction. This is where Dutton Creek joins other tributaries of Castle Creek, so the area is rich with meadows and streams. As you follow the Dutton Creek Trail north, it winds through grassy areas interspersed with giant conifers. This is a favorite grazing and bedding area for elk and deer. A quiet hiker can usually view these animals in this area, especially at early morning and late afternoon.

Your climb is eased further up the trail by the shade of mountain hemlock, Tsuga mertsensiana,and Shasta red fir, Abies magnifica-procera. This area has been cut by the seasonal streams which run along the length of Dutton Creek, so it is interesting to note how they contribute to this sometimes dry upper portion of the Rogue River Basin. The entire length of Dutton Creek represents a moister, more temperate environment (therefore possessing greater plant and animal diversity) than the demanding conditions evident on the rim.

As the Dutton Creek Trail reaches the Rim Village area, hikers can make use of facilities such as restrooms, a visitor center operated during the summer months, the Sinnott Memorial Overlook, as well as the cafeteria, gift shop, and hotel. The trail route continues along the west side of the caldera and leads to Discovery Point. Interpretive signs point out the discovery of the lake by white miners in 1853 and some of the early history.

Further west, this route encounters the Lightning Spring Trail. At one time a fire control road, the Lightning Spring Trail now serves as an access for stock users who are still confined to the old PCT as they traverse through the park. There is a hitching post for horses, mules, and llamas a quarter mile below this junction so that their users can walk a short distance to see Crater Lake. Beyond the Lightning Spring picnic area, the new PCT follows an old road for five miles to the North Junction. This required no new construction, thereby lessening the impact on fragile soils and vegetation.

As you climb toward 7,500 feet in elevation the Watchman Lookout becomes more apparent. Completed in 1933, this structure is an active fire lookout that is staffed during the summer months. It is open to visitors and provides a great view not only of the lake, but also the surrounding forests and lakes. Look closely and see how many of the major mountains and peaks you can identify.

Once you descend to the Watchman Overlook (sometimes called “the corrals” because of a fence used to protect the remaining vegetation), the new PCT stays above Rim Drive in rounding Hillman Peak. This affords a relatively easy climb of Hillman, which has the distinction of being the rim’s highest point. From here it is a fairly easy descent to the North Junction, so named because this is where the road to Diamond Lake separates from the Rim Drive which continues east and then back to Park Headquarters in Munson Valley.

Near North Junction the trail takes us away from the caldera rim. At this point you will find a desert- like locality with only a sedges and succulents anchoring the soil. This is similar to the Pumice Desert, an area of the park which the PCT skirts on its way north to Mount Thielson. The soils here are deep enough so that you will sink a little with every step. This effect is magnified by the digging and burrowing of rodents, which is experienced if you drop into holes and tunnels made by these creatures.

The areas of open soil soon give way to mountain hemlock and more sedge. At this point the PCT bids farewell to the abandoned road bed and we find ourselves losing elevation as we continue our northerly trek. As you descend, the ground becomes more level while the trail begins to skirt around the base of Grouse Hill. This is a favorite nesting area for several different birds of prey, sometimes called raptors. Yellow-bellied marmots, Marmota flaviventris, as well as smaller rodents such as squirrels and chipmunks occupy the boulders at the base of Grouse Hill. They can sometimes be heard barking and chirping insults at each other.

A newly-designated camping area for hikers is located near the trailhead, but no water is available here. It does, however, signify an end to the rerouted PCT whereby hikers can continue north to Diamond Lake or reach their shuttled vehicle if on a day trip. The new trail can be followed once the snow has gone and may have areas where washing and erosion are evident. In spite of these imperfections, however, all slopes are moderate and do not represent unusually rigorous hiking conditions in comparison to the rest of the Pacific Crest Trail.

Brenda Bridges has worked as an archaeologist on the Rogue River National Forest and at Crater Lake National Park.

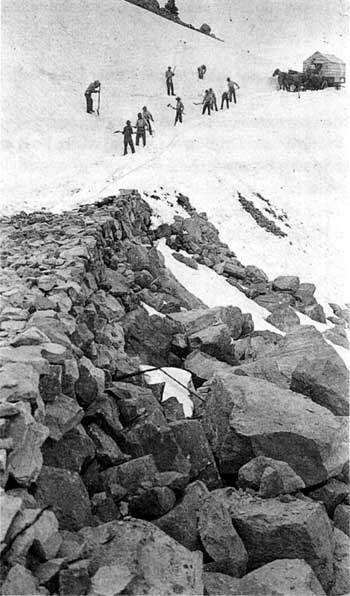

Crew opening the old rim drive near the Watchman in 1917. This is now part of both the Pacific Crest Trail and the bottom of the Watchman trail.

Earl Russell Bush photo, NPS files.

Panorama of Mt. Mazama from the southwest, sketched by Howel Williams.

Howel Williams, The Geology of Crater Lake National Park, Oregon, Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1942, p. 66.

Other pages in this section