The areas of open soil soon give way to mountain hemlock and more sedge. At this point the PCT bids farewell to the abandoned road bed and we find ourselves losing elevation as we continue our northerly trek. As you descend, the ground becomes more level while the trail begins to skirt around the base of Grouse Hill. This is a favorite nesting area for several different birds of prey, sometimes called raptors. Yellow-bellied marmots, Marmota flaviventris, as well as smaller rodents such as squirrels and chipmunks occupy the boulders at the base of Grouse Hill. They can sometimes be heard barking and chirping insults at each other.

A newly-designated camping area for hikers is located near the trailhead, but no water is available here. It does, however, signify an end to the rerouted PCT whereby hikers can continue north to Diamond Lake or reach their shuttled vehicle if on a day trip. The new trail can be followed once the snow has gone and may have areas where washing and erosion are evident. In spite of these imperfections, however, all slopes are moderate and do not represent unusually rigorous hiking conditions in comparison to the rest of the Pacific Crest Trail.

Brenda Bridges has worked as an archaeologist on the Rogue River National Forest and at Crater Lake National Park.

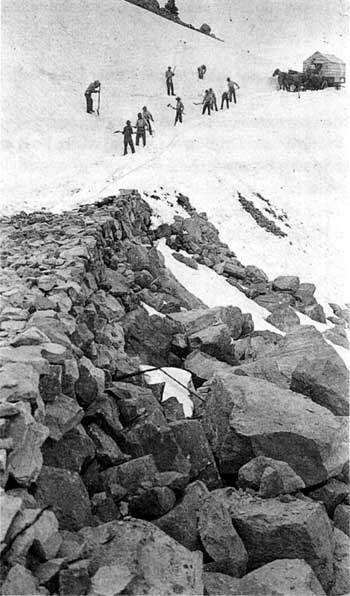

Crew opening the old rim drive near the Watchman in 1917. This is now part of both the Pacific Crest Trail and the bottom of the Watchman trail.

Earl Russell Bush photo, NPS files.

Panorama of Mt. Mazama from the southwest, sketched by Howel Williams.

Howel Williams, The Geology of Crater Lake National Park, Oregon, Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1942, p. 66.

***previous***