Wandering Through Wildflowers

The hiking trails at Crater Lake National Park will take you to elegant floral displays as the snows recede and spring seeps up the caldera walls. Botanists have found roughly 700 species of flowers, ferns, and conifers in the park. You can sample a rich diversity of plants by simply stretching your legs and setting out from the macadam.

Drawing by Amelia Bruno. Drawing by Amelia Bruno. |

While snow drifts still surround Park Headquarters, western flowering dogwood, Cornus nuttallii, Shelton’s violet, Viola sheltonii, and pink fairy slippers, Calypso bulbosa, are luring bees in the warmer depths of Red Blanket Canyon, on the lower trail to Stuart Falls. Legions of lupines, Lupinus latifolius, and scarlet paintbrushes,Castilleja miniata, greet you when summer’s heat has opened the footpaths along Annie Creek and into the Castle Crest Wildflower Garden.

Drawing by Amelia Bruno. Drawing by Amelia Bruno. |

You might be pleased by a walk on the south-facing Garfield Peak Trail, located east of Crater Lake Lodge. Melting snowfields water a delightful mix of plants through the summer. As you pause for yet another splendid view of the lake, you can admire the blue blossoms of squaw carpet, Ceanothus prostratus, or later in the season see shocking purple and pink beardtongues, Penstamon davidsonii and rupicola.

Midsummer brings monkeyflowers into bloom on wet ledges and streamsides. Pink and yellow monkeyflowers,Mimulus lewisii and M. guttatus, form festive natural bouquets on the shores of Crater Lake and even in roadside ditches. The relentless sunshine sears the well-drained treeless expanses at high elevations. Graded paths up Mount Scott and Crater Peak take you to pumice fields tinted red with the fading and drying leaves of fleeceflower, Polygonum newberryi. When fleeceflower is conspicuous on the caldera and in Pumice Desert, brilliant yellow-flowering shrubs beckon butterflies along the eastern side of Rim Drive. This is rabbitbrush, Chrysothamnus nauseosus, a cousin to the locally rare sagebrush, Artemisia tridentata. Rabbitbrush draws on reserves in its deep root system to flower so late in the year. In doing so, it seems to defy drought conditions common to the upper slopes of Mount Mazama during summer and early autumn.

Drawing by Amelia Bruno. Drawing by Amelia Bruno. |

Frost and early snow withers vegetation on the rim in September, but pearly everlasting, Anaphalis margaritacea, holds persistent white flowers at lower elevations until later in the year. Cold nights finally leach the pink from loose mist- like masses of ticklegrass, Agrostis hyemalis, at Spruce Lake which is located due west of Llao Rock near the park boundary. By November, new snow drifts end another season of wandering through the wildflowers.

Peter Zika recently updated checklists of plants at Crater Lake and Oregon Caves. He is a professor of botany at Oregon State University in Corvallis. Oregon.

Even the seemingly barren Pumice Desert has wildflowers in June and July. Photo by Glen Kaye.

Even the seemingly barren Pumice Desert has wildflowers in June and July. Photo by Glen Kaye.

A Pause in the Panhandle

When Congress established Crater Lake National Park in 1902, the enabling legislation called for the reservation to take a rectangular form which encompassed much, but not all, of the mountain that holds the nation’s deepest and clearest body of water.

Highway 62 through Panhandle. Highway 62 through Panhandle. |

Congress excluded most of the lower elevation forests of Mount Mazama which has trees of comparatively greater size than what thrives in the higher elevations. Rising visitation fueled appropriations for improving park’s roads throughout the 1920s, and this led the National Park Service to begin negotiating for a small, but impressive, forest corridor along Annie Creek. This addition to the park eventually took the form of a Congressionally-approved land transfer from the U.S. Forest Service in 1932. It effectively extended the park’s south entrance and consisted of 973 acres. Due to its tongue-like configuration, this area quickly became known as the “panhandle.”

Most visitors who journey between Crater Lake and the Klamath Basin never leave their cars when traveling along the two and a half miles of road that runs through the panhandle. If they did, many of them would have a chance to distinguish among three great coniferous tree species native to several western states: ponderosa pine(Pinus ponderosa), sugar pine (P. lambertiana), and Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). The more adventurous might enjoy a walk along Annie Creek, where the riparian area harbors many of the plant species found in the panhandle. The panhandle area, in fact, has the greatest botanical diversity of anywhere in the park. With more than 230 species known in this locality, it is relatively rich when compared to the total park count of only 700. This is impressive when one considers the panhandle’s size is barely more than half of one percent of Crater Lake National Park’s 183,000 acres.

Cearl evidence of beavers gnawing a cottonwood along lower Annie Creek, photo by O.L. Wallis, 1947.. Cearl evidence of beavers gnawing a cottonwood along lower Annie Creek, photo by O.L. Wallis, 1947.. |

For those interested in stretching their legs and seeing the panhandle on foot, there is a highly recommended place along Highway 62 for motorists to pause and perhaps saunter into the forest. This is a picnic area located near the south entrance, where the prospective hiker can find all of those conifer species previously mentioned in close proximity to the pavement, but even more sylvan variety if they descend to the stream. Down logs provide an opportunity to cross Annie Creek and explore the pine-dominated woodland on the other side, or perhaps discover the work of beavers (Castor canadensis) on deciduous trees such as aspen (Populus tremuloides) and alder (Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia)within the drainage.

The only other place to stop is a small paved pull out located about two miles further north. It served as the park’s south entrance prior to 1932 and still has a boundary marker from early this century. After a peek into Annie Creek Canyon, carefully cross the highway and go south a few yards to the small wetland formerly called Wildcat Camp. This area has standing water in spring through early summer and contains black cottonwood (Populus balsamifera ssp. trichocarpa) whose broad leaves contrast markedly with the surrounding coniferous forest. From here it is only one tenth of a mile before the intrepid cross-country walker reaches the park boundary by going due west. It is, of course, clearly signed and also very evident due to extensive clearcutting on adjacent land.

Human-induced change in the forest profile is, however, not confined to places outside the park. An astute visitor can see stumps resulting from attempts to control insects ponderosa pine, as well as numerous fire scars that bear witness to prescribed burning within the panhandle. From the 1930s to the 1960s, insect control work in this locality focused on the western pine beetle (Dendroctonus brevicomis) which preyed on older or drought-weakened ponderosa pine. The fear that this insect could spread into apparently healthy stands led to periodic cutting or removal of trees throughout the forest corridor. Prescribed burning is a more recent management program in the panhandle, having begun in 1976. It centered on evidence that regeneration of ponderosa pine was being stymied in areas where fire had been suppressed historically. Management-ignited burning in the panhandle consequently aimed at promoting the pine at the expense of its associate, white fir (Abies concolor), which tends to shade out the sun-loving ponderosa.

National Park Service employees fall a Ponderosa Pine as part of beetle control. Photo by Vicki Boucher.

National Park Service employees fall a Ponderosa Pine as part of beetle control. Photo by Vicki Boucher.

With an elevation range of 4300 to 4800 feet above sea level, this area is easily accessible from May to November. There are no formal trails in this part of the park, but remnants of the old Crater Lake Highway and an earlier wagon road make fine footpaths for visitors who want to identify plants or have a relaxing jaunt among the trees. A number of shrubs can be seen in open and dry areas, with snowbrush(Ceanothus velutinus) and greenleaf manzanita (Arctostaphylos patula) being very common. More shaded places often feature sticky currant (Ribes viscosissimum) and two types of huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum and V. scoparium). Wildflowers generally bloom in June and July, but a bigger splash of color comes in October when the leaves of deciduous trees turn yellow and orange. There are few places in the park that rival the panhandle, especially that portion of Annie Creek which runs through it, for walking on clear and crisp autumn days. At such a time, only an occasional sound associated with vehicle traffic on the highway could disturb the sense of solitude that a visitor gains by pausing to explore this magnificent portal to the park.

Steve Mark is the park historian at Crater Lake. He has been the editor of Nature Notes since its revival in 1992.

Ron Mastrogiuseppe is a forest ecologist who has worked as a seasonal naturalist at Crater Lake.

Drawing by L. Howard Crawford, 1936.

Drawing by L. Howard Crawford, 1936.

Fossil Finds and the Age of Oregon Caves

How old is a hole in the ground? How do you pin a date on what has dissolved away? Geologists have a hard time figuring out when Oregon Caves formed. To dissolve marble made of calcite, all you need is a weak acid, such as carbon dioxide dissolved in water which is the fizz in soft drinks. Yet understanding how something works does not always help in knowing how fast it works.

For example, the yearly amount of dissolved calcite exiting by way of Cave Creek is known. The entire cave could have been dissolved out in ten thousand years if the same concentration of dissolved calcite left the cavern every year. That is a very big if! Water exiting the cave during its birth probably had less calcium in it. The size of stream gravels and horizontal notches dissolved on cave walls indicate massive flooding at one time and thus resulted in a much faster enlargement of Oregon Caves.

Another way to estimate the age of Oregon Caves is to compare it with similar mountain caves which have been better dated. Most caves on steep slopes form close to the earth’s surface. Since mountains erode relatively fast, geologically speaking, most such caves do not survive long before they are breached by erosion and destroyed. These caves usually are older than ten thousand years but rarely last more than a hundred thousand. Such comparisons, however, are dangerous. There may have been geological or hydrological factors affecting Oregon Caves that differed substantially from those in superficially similar topography which sped up or slowed down cave formation.

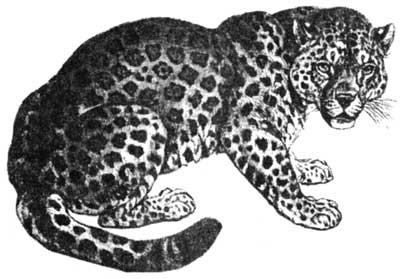

Geologists can fix the minimum age of Oregon Caves because of what it has preserved. While most surface features are eroding or decomposing on the surface, things can be deposited in caves. An example is the jaguar, Panthera onca, found in Oregon Caves during August of 1995. The size of its bones compares with jaguars living in North America between 15,000 to 40,000 years ago. As the last Ice Age ended roughly 10,000 years ago, the size of jaguars decreased. This seems to have happened because being smaller and thinner helped jaguars survive in an increasingly warmer climate.

Sketch of modern jaguar. The Pleistocene relative was substantially larger. Drawing #89 from Jim Harter (comp.) 1419 Copyright Free Illustrations, New York, Dover Publications, 1979.

Sketch of modern jaguar. The Pleistocene relative was substantially larger. Drawing #89 from Jim Harter (comp.) 1419 Copyright Free Illustrations, New York, Dover Publications, 1979.

The jaguar’s bones could have been buried and then later washed into a much younger Oregon Caves. The fact that this may be the most complete jaguar fossil ever found, however, is strong evidence against this possibility. It would thus seem reasonable to assert that the cave must be at least as old as the jaguar.

Comparing evidence of past life (fossils) and erosion rates with similar examples usually give scientists only approximate dates. To be more precise, methods which hinge on changes occurring at a uniform rate are needed. Uranium atoms are consistently unstable and “overweight,” but release particles at constant rates. This changes the uranium into another element called thorium. One of the best materials to use for this dating method is calcite, such as the crystal layer left by water on the jaguar skull in Oregon Caves.

Since uranium is soluble in water, whereas thorium is not, the layer of calcite that formed on the jaguar skull at first contained uranium but no thorium. As time passed, uranium decayed to thorium. The thorium to uranium ratio thus increases over time at a constant rate and can be dated. Unlike most calcite formed on the earth’s surface, calcite in caves tends to be very dense and waterproof. Therefore, compared to surface calcite, cave calcite is much less likely to have uranium leach out and thus give a wrong calculation for age of the calcite.

Other ways exist that can independently confirm the accuracy of dates determined by uranium/thorium ratios. Natural radiation traps free electrons in defects in calcite crystals. The rate of trapping is determined by background radiation. The energy of the trapped electrons can be measured and a date derived from the ratio between this figure and the trapping rate.

Oregon Caves has been explored for more than a century. Not until 1995 did cavers uncover fossils in its passages. U.S. Forest Service photo, 1927.

Oregon Caves has been explored for more than a century. Not until 1995 did cavers uncover fossils in its passages. U.S. Forest Service photo, 1927.

There is yet another way to get a more precise age for the jaguar. Carbon 14, like uranium, is also composed of “fat” atoms that release particles at constant rates. Since carbon 14 only forms in the earth’s atmosphere and becomes part of the protein of live animals, the ratio of it and more stable carbon starts to change when the animal dies. If the age of the skull is 45,000 years old or younger, there is likely to be enough carbon 14 remaining in the skull for a fairly precise age to be calculated. The uranium-thorium date of the calcite will help determine whether it is worthwhile to obtain a carbon 14 date on the skull.

Other fossil bones, most likely from a single grizzly bear, Ursus horribilis, have also been found in Oregon Caves. With only about one percent of the original protein remaining in the bones, investigators could determine that no carbon 14 was left. The age of the bones and the cave, therefore, must be at least 46,400 years old.

Why should we be concerned with how old things are? An important part of the answer has to do with park managers being able to better protect, preserve, and restore ecological processes if they know how fast and how often events occur. We may also find that our understanding of time is highly relative. A person’s emphasis on man-made things might change when they can perceive time as going beyond human experience and forming part of a broader history. Since we have been around for a very short period, relatively speaking, it may be difficult sometimes to accept that there is far more to the past than one life form’s view of itself as the goal of time. All species are kin if you go back far enough in time; all rocks come from the same source.

John Roth is the natural resources management specialist at Oregon Caves National Monument and a geologist by training.

Protection for the Coyotes by Frank Solinsky, 1931 Nature Notes

Protection for the Coyotes by Frank Solinsky, 1931 Nature Notes

Other pages in this section