A Pause in the Panhandle

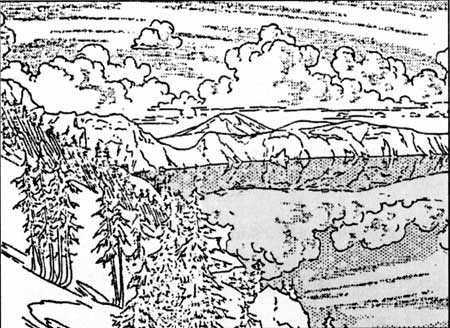

When Congress established Crater Lake National Park in 1902, the enabling legislation called for the reservation to take a rectangular form which encompassed much, but not all, of the mountain that holds the nation’s deepest and clearest body of water.

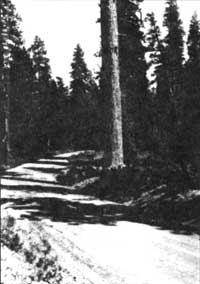

Highway 62 through Panhandle. Highway 62 through Panhandle. |

Congress excluded most of the lower elevation forests of Mount Mazama which has trees of comparatively greater size than what thrives in the higher elevations. Rising visitation fueled appropriations for improving park’s roads throughout the 1920s, and this led the National Park Service to begin negotiating for a small, but impressive, forest corridor along Annie Creek. This addition to the park eventually took the form of a Congressionally-approved land transfer from the U.S. Forest Service in 1932. It effectively extended the park’s south entrance and consisted of 973 acres. Due to its tongue-like configuration, this area quickly became known as the “panhandle.”

Most visitors who journey between Crater Lake and the Klamath Basin never leave their cars when traveling along the two and a half miles of road that runs through the panhandle. If they did, many of them would have a chance to distinguish among three great coniferous tree species native to several western states: ponderosa pine(Pinus ponderosa), sugar pine (P. lambertiana), and Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). The more adventurous might enjoy a walk along Annie Creek, where the riparian area harbors many of the plant species found in the panhandle. The panhandle area, in fact, has the greatest botanical diversity of anywhere in the park. With more than 230 species known in this locality, it is relatively rich when compared to the total park count of only 700. This is impressive when one considers the panhandle’s size is barely more than half of one percent of Crater Lake National Park’s 183,000 acres.

Cearl evidence of beavers gnawing a cottonwood along lower Annie Creek, photo by O.L. Wallis, 1947.. Cearl evidence of beavers gnawing a cottonwood along lower Annie Creek, photo by O.L. Wallis, 1947.. |

For those interested in stretching their legs and seeing the panhandle on foot, there is a highly recommended place along Highway 62 for motorists to pause and perhaps saunter into the forest. This is a picnic area located near the south entrance, where the prospective hiker can find all of those conifer species previously mentioned in close proximity to the pavement, but even more sylvan variety if they descend to the stream. Down logs provide an opportunity to cross Annie Creek and explore the pine-dominated woodland on the other side, or perhaps discover the work of beavers (Castor canadensis) on deciduous trees such as aspen (Populus tremuloides) and alder (Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia)within the drainage.

The only other place to stop is a small paved pull out located about two miles further north. It served as the park’s south entrance prior to 1932 and still has a boundary marker from early this century. After a peek into Annie Creek Canyon, carefully cross the highway and go south a few yards to the small wetland formerly called Wildcat Camp. This area has standing water in spring through early summer and contains black cottonwood (Populus balsamifera ssp. trichocarpa) whose broad leaves contrast markedly with the surrounding coniferous forest. From here it is only one tenth of a mile before the intrepid cross-country walker reaches the park boundary by going due west. It is, of course, clearly signed and also very evident due to extensive clearcutting on adjacent land.

Human-induced change in the forest profile is, however, not confined to places outside the park. An astute visitor can see stumps resulting from attempts to control insects ponderosa pine, as well as numerous fire scars that bear witness to prescribed burning within the panhandle. From the 1930s to the 1960s, insect control work in this locality focused on the western pine beetle (Dendroctonus brevicomis) which preyed on older or drought-weakened ponderosa pine. The fear that this insect could spread into apparently healthy stands led to periodic cutting or removal of trees throughout the forest corridor. Prescribed burning is a more recent management program in the panhandle, having begun in 1976. It centered on evidence that regeneration of ponderosa pine was being stymied in areas where fire had been suppressed historically. Management-ignited burning in the panhandle consequently aimed at promoting the pine at the expense of its associate, white fir (Abies concolor), which tends to shade out the sun-loving ponderosa.

National Park Service employees fall a Ponderosa Pine as part of beetle control. Photo by Vicki Boucher.

National Park Service employees fall a Ponderosa Pine as part of beetle control. Photo by Vicki Boucher.

With an elevation range of 4300 to 4800 feet above sea level, this area is easily accessible from May to November. There are no formal trails in this part of the park, but remnants of the old Crater Lake Highway and an earlier wagon road make fine footpaths for visitors who want to identify plants or have a relaxing jaunt among the trees. A number of shrubs can be seen in open and dry areas, with snowbrush(Ceanothus velutinus) and greenleaf manzanita (Arctostaphylos patula) being very common. More shaded places often feature sticky currant (Ribes viscosissimum) and two types of huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum and V. scoparium). Wildflowers generally bloom in June and July, but a bigger splash of color comes in October when the leaves of deciduous trees turn yellow and orange. There are few places in the park that rival the panhandle, especially that portion of Annie Creek which runs through it, for walking on clear and crisp autumn days. At such a time, only an occasional sound associated with vehicle traffic on the highway could disturb the sense of solitude that a visitor gains by pausing to explore this magnificent portal to the park.

Steve Mark is the park historian at Crater Lake. He has been the editor of Nature Notes since its revival in 1992.

Ron Mastrogiuseppe is a forest ecologist who has worked as a seasonal naturalist at Crater Lake.