Repeat Photography and Landscape Change

Introduction

The nature of nature is change. The physical and biological worlds in which we exist are constantly becoming different in myriad ways. A useful technique in comparing landscape changes occurring during a human lifetime and in analyzing long-term trends is repeat photography. Repeat photography is the art of locating the actual site of an old photograph, duplicating the position of the original camera and taking a repeat image of the same scene.

Background detail is critical in locating the position of the historic photo point and photographer. When possible, the same or similar film and camera type are used. A continuous record of change will result from frequent repeated photographs, documented with relevant information. This approach is an important part of monitoring protocol for interpreting the story of a landscape. Old photographs create much visitor interest, and with repeat photography, a better understanding of the natural processes operating in the landscape may be more easily communicated. Once resource management activities are implemented, such historical time-lapse photographs of changes are a baseline for future management proposals and actions.

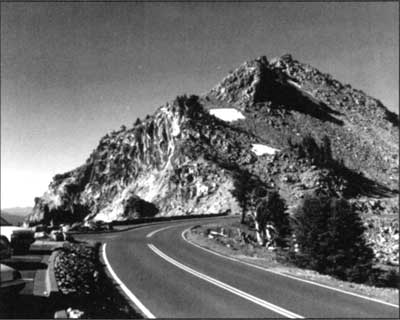

The first known photograph of the Crater Lake caldera was taken by Peter Britt of Jacksonville in August 1874. Since then, Crater Lake has been the focus of many photographs. This allows for the comparison of known time interval photo pairs, which can establish a record of erosion rates and vegetation change in and near the caldera.

Some of the earliest photographic records of the park landscape away from the lake were during a vegetation survey of backcountry areas in 1936. These photographs have been useful in documenting tree encroachment into pumice fields and measuring cause-effect changes resulting from historical forest fires or sheep grazing that took place prior to the park’s establishment. Lodgepole pine encroachment into pumice fields, for example, began shortly before the 1936 photographs were taken. Reduced precipitation during the 1920s and 1930s, as well as minimal snowpacks for most of that period, extended the growing season significantly and allowed for successful conifer seedling establishment. An obvious change in forested landscapes has been the trend toward an increase in conifers, a shift away from herbaceous communities to those dominated by woody shrubs and trees. This is a common trend in western landscapes during the past century. Trends in vegetation change are driven by shifts in climatic factors and by human-induced disturbances such as Indian burning practices and recent fire suppression programs.

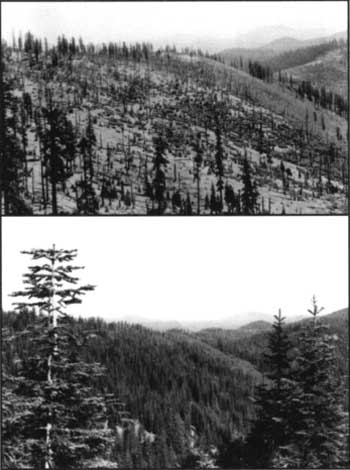

The Watchman in 1901 (top) and in August 1996 (bottom).

Top photo by J.S. Diller, U.S. Geological Survey.

Progress during 1996

Last year the Crater Lake Natural History Association made a grant to John Salinas and Dick Miller to produce a set of paired photographs. One black and white photograph in each set was to be a print of an image taken approximately 100 years earlier. This became possible when a large number of late 19th century photographs were found in the U.S. Geological Survey’s library in Denver. These photos had been snapped by J.S. Diller, a USGS geologist who can be credited with making the first scientific studies of Crater Lake beginning in l 883. Diller’s most important work, a professional paper on the park’s geology, appeared in 1902 — the same year that Crater Lake National Park was established. Many of the photos found in Denver were intended to illustrate his paper, though he used only a small fraction of them in the publication.

The current project began with Salinas and Miller spending hours pouring over copy prints and negatives which the National Park Service had recently acquired, in order to determine which ones might best show change in the landscape. A historic photograph was selected that has Garfield Peak as backdrop, so as to use Crater Lake Lodge as reference in the modern view. Another image showed the Watchman Overlook (on the west Rim Drive) without the fencing or parking lot. Diller’s photographs were also useful for studying change in the caldera. For example, historic views which include the lake are important to detect contrasts in the shoreline or caldera walls that become evident with time. Moreover, some of the photos repeated around Wizard Island illuminated the natural variability in lake levels and thereby demonstrated how that water body can be dynamic through time.

Two incidents in particular may help convey what it is like to set your boots in the precise footprint of an early photographer. In the first instance, it was mid afternoon on the crater rim of Wizard Island. The print held in the hands of repeat photographers clearly showed Llao Rock behind a bit of the rim with a whitebark pine growing out of a small mound of cinder covered by pinemat manzanita. There was only one place on the island where the crater and Llao Rock would match as in the photograph. But the whitebark pine was not to be seen. Like lightning, the realization that the pine was now a sun-bleached skeleton on the same small mound of cinder still covered with manzanita filled the repeat photographers with an almost surreal awe.

The site of the second incident was very easy to find since summer visitors take photographs from that spot every day. Something was not right, however, as Salinas viewed Victor Rock (where the Sinnott Memorial was built in 1930) from a point on the promenade where the Mather plaque is affixed. Somehow he needed to angle his camera a bit higher to take in more of the sky and less of the lake. Suddenly he realized that this point on the promenade was not the exact spot from where Diller had taken his photograph. The only way to replicate the historic image was to descend about 50 feet into the caldera. As one looks into the caldera from this point, it would be easy to imagine a photographer on that spot — but not Salinas. One slip on the loose pumice and that would be the end of this and several other projects. Consequently, the repeat photograph will have a slightly different angle.

Summit of cinder cone on Wizard Island, Crater Lake in 1901 (top) and today (bottom).

Top photo by J.S. Diller, U.S. Geological Survey; bottom photo by John Salinas.

Future work

Each person and every piece of equipment can be severely tested in this harsh environment. As the fallen mast of the Phantom Ship was being photographed from a tour boat making its rounds last summer, Salinas noticed an odd sound to the shutter on his large format (4 by 5 inch) camera. The shutter seemed to be hanging up after a cold night in the park. As it turned out, the same shutter failed to capture a dozen photographs around the lake and some from the top of Mount Scott. These photographs will have to be retaken during the summer of 1997 since the 1996 season ended without obtaining a complete set of repeat images. The project’s goal is to display copies of the original and repeat photographs in park exhibits and throughout a number of buildings. We hope this first attempt at repeat photography will lead to another project which will produce a book of large black and white paired photographs in time for the centennial of Crater Lake National Park in 2002.

The authors would like to acknowledge the Crater Lake Natural History Association’s sponsorship of this and other endeavors. The repeat photography project would not have been possible without discovery of the Diller photos by former seasonal interpreter Mike Smith and the assistance provided by USGS librarians in Denver.

History of the Crater Lake Wilderness Ski Race

The Crater Lake Wilderness Race between Fort Klamath and Crater Lake Lodge was held annually from 1927 to 1938. The grueling race, originally 42 miles long, gained over 2,800 feet in elevation and challenged skiers with varying snow conditions. The race was shortened to 32 miles in 1932, five miles in 1936, and by about 1938 both the race and the accompanying winter carnival were discontinued. In 1978, the race was revived by the Alla Mage Skiers and Crater Lake National Park and now attracts about 100 skiers annually.

The “Carnival” included snow balling, toboganning, sleighing, short races for high school students and adults, as well as ski jumping (the record jump was 151 feet), sled dog races, barefoot races and a homing pigeon race. There was usually an all-day dance in the community hall.1 The Carnival and the historic race attracted as many as 4,000 spectators.

In the early years, a 16-mile race from the Rim to Fort Klamath was the “down mountain” or “trail breaker” race for the longer race; but later, the “down mountain” race was the more popular.

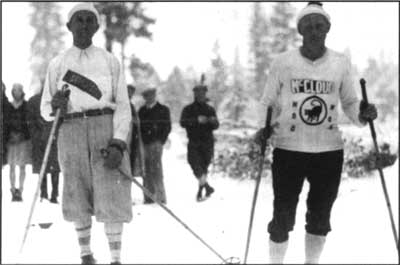

In 1927, a total of 24 skiers entered the race. The course followed the Crater Lake Highway to the Lodge and back, with contestants required to keep within one half mile of this course. Any style, make, pattern or length of ski and harness could be used; however, metal skies were barred. Manfred Jacobson, “a sandy haired logger” from McCloud, California, and Waldemar Nordquist, “a powerful lumber piler” from Klamath Falls, fought for first place. Jacobson had a peculiar “slide-slide and then skip technique like a skating stroke – his entire body swinging to the rhythm of the forward lunge.” Nordquist, a former Swedish Army Captain, used arms and ski sticks more. The Klamath Falls Evening Herald reported that the two Swedes were “…engaged in one of the greatest battles of endurance, of wits and of the elements in the history of the Pacific Coast.” New snow made the going “tough and hard,” but the two men arrived at the lodge together. Jacobson had let Nordquist pass him on the way to the rim, requiring him to break trail and use precious energy. Returning downhill, Jacobson lost a ski and Nordquist a ski stick. The lead changed when they stopped to retrieve the equipment. Jacobson crossed the finish after 7 hours and 34 minutes, to win the first prize of $250. Nordquist, 21 minutes behind, won the $100 second prize. Nels Skjersaa of Bend and Everett Puckett of Klamath Falls battled for third place. Skjersaa claimed the $50 prize, and Puckett won a radio set. Harry C. Francis of Klamath Falls was fifth, winning a rifle, and Otto Hagen of Brightwood and Andy Versto of Fort Klamath tied for sixth place.

The 1927 race brought huge crowds to Fort Klamath.

Photo courtesy Klamath County Museum.

The second race had 16 entrants: “…stalwart athletes, most of whom bear names reminiscent of the snow-clad mountains of northern Europe.” Twelve of the racers dropped out, “…unable to keep pace with the quartet of northlanders: Manfred Jacobson, Nels Skjersaa, Waldemar Nordquist and Emil Nordeen of Bend.” Jacobson won the race for a second time, in 6 hours and 13 minutes. Emil Nordeen was eight minutes behind.

In 1929, Emil Nordeen, “the crafty ‘Old War Horse’ of Bend,” won the race in a record time of 5 hours 57 minutes. At 43 years, he was the oldest as well as the fastest skier. Skjersaa was second and 28 minutes behind Nordeen. Emil was awarded the solid silver “Klamath Cup” which stood 38 inches high and was trimmed with gold. The winner kept the cup only one year, but Nordeen could keep a smaller 6-inch high cup called the “Shadow of Klamath.”

Manfred Jacobson won in 1930, with a time of 7 hours, 40 minutes and 30 seconds. Nordeen was 34 seconds behind Jacobson and Skjersaa placed third. The other two entrants, Nordquist and Oliver Puckett of Keno, dropped out. The racers had to battle two feet of new snow in the park but were forced to make a five-mile loop at the finish because there was virtually no snow at Fort Klamath.

In 1931, there were four entrants, but only two finished. Nordeen, who came close to not entering the race because of an injury, broke the record at 5 hours and 35 minutes. Jacobson placed second. Ivar Amoth of Bend broke a ski and Oliver Puckett dropped out after 34 miles. Nordeen had now won the Klamath Cup for the second time, and thus gained permanent possession of it (see the article by Kenneth Åström). The Skyliner Skiing Club members of Bend carried Nordeen on their shoulders to the community hall. The newspaper reported 848 cars parked on the grounds.

In 1932 the race was shortened to 32 miles, but a new ski jump was inaugurated and buses brought spectators to the events.2 A record 4,000 people attended the Snow Show. This was the sixth year that Oliver Puckett had entered the long race, and with his lucky rabbit’s foot, he finally won in 4 hours and 26 minutes. He was the first native born American to win the race. Pete O. Hedberg of Modoc Point was 30 minutes behind, while Rudy Lueck, a park ranger at Crater Lake, was third.

Hedberg was the other two-time winner of the races. Another Swede by lineage, he won the race held in 1933. After poor snowfall canceled the race in 1934, Hedberg retired the second Klamath Cup with a win in 1935. During that race he was operating under a slight handicap; he had broken his leg several months earlier and the cast was removed only three weeks before the competition.

Oliver Puckett almost won in 1933, but Pete Hedberg passed him in the last mile. Puckett won the second place trophy, called “the Watchman.” Rudy Lueck was once again third. Hedberg’s winning time was 4 hours and 30 minutes, four minutes ahead of Puckett. Rudy Lueck was only a few yards behind Hedberg in the 1935 race, with Harold Paulson of Bend third to complete a “horse race finish.” Puckett led the racers to the rim, but then dropped behind on the return.

After the 1935 race, the Evening Herald reported that “Skiers and officials of the Crater Lake Ski Club and Klamath Winter Sports Association are inclined strongly to the opinion that the long race is too tough, and now that Hedberg, by virtue of his two victories, has won the cup, the event might as well be dropped from the Klamath winter sports program.” The race was thereby shortened to five miles in 1936 and 1937. Frank Drew of Klamath Falls and Delbert Denton of Fort Klamath were the winners these two years. A race of only one mile in length was held at the rim of Crater Lake in 1938.

Other than the sometimes dramatic finish of the men’s race, this event had many highlights. Myrtle Copeland of Fort Klamath entered the 1927 race with an unusual handicap; she forgot her boots and had to ski in house slippers. Needless to say she did not win, but nine years later she won the five-mile race. The Briscoe sisters of Fort Klamath often entered and won the shorter women’s race. Ida, Vinnie and Peggie Briscoe also won the relay race in 1933. The Drew family of Klamath Falls also had winners in many of the shorter races. Frank and Greer often competed for first and second place in the high school and college student races. Lester Hellens of Seattle and Millard Briscoe of Wood River won the first two “down mountain” races.

The ski jump event in 1932.

Photo by Guy Hartell.

Emil Nordeen rekindled memories of the long race in 1960, when he donated his Klamath Cup to the Swedish Ski Association during the Olympic Games held at Squaw Valley. The cup was subsequently used in team races in Sweden and finally retired. In 1980, with the aid of Jay Bowerman (two-time U.S. Olympic Biathlon Team Member) and the Bend Bulletin newspaper, the Swedes agreed to award the cup in the 37-mile Kalvtraskloppet race in northern Sweden. The race, which annually draws about 1000 skiers, starts 30 miles from Nordeen’s birthplace of Norsjo. The trophy will remain in a museum in Umeå near the race site, and the winner receives either a small replica or a photograph-diploma symbolic of victory.

Unpredictable snow conditions have forced the sponsoring groups to keep the modern races totally within Crater Lake National Park. Four races are usually planned for around the second weekend in February, and cover distances of 10, 15, 24 and 39 kilometers (6, 9, 15 and 24 miles). Due to the terrain and wilderness conditions in the park, the courses are not machine-groomed but are set by skiers. They begin and end near Park Headquarters. Emil Nordeen, then 81, started the 1978 race, as did Pete Hedberg at age 73. Gary Dalesky of Bend, my former OIT ski student, won the long race that year and many of the later races.

References: Klamath Falls Herald and News articles by Bruce Meadows (1/26/75), Lee Juillerat (2/9/78, 2/10/78, 2/22/78, and 3/23/78); and Catherine Harris (2/6/87).

Notes

1 This building no longer stands. It was located on a lot between what is now the Cattle Crossing Cafe and the Fort Klamath Lodge.

2 The ski jump was located adjacent to the present day Annie Creek Snopark, just south of the park boundary.

The Long Forgotten Klamath Camp

By Kenneth Astrom

A remarkable silver trophy was displayed in the window of Monark’s Sporting Goods store on Kungsgatan Street at Umeå (Sweden), in 1961. It had been sent to Umeå by the Swedish Ski Association to be used as a challenge trophy in one of the Swedish Masters competitions. It was never awarded to anyone, as there was confusion as to the interpretation of the conditions set by the donor. As a result, the trophy lay forgotten until April 1964, when it was found in a display closet in Monark’s attic. The find started a debate when the news was published in the local press, and the question arose regarding how much control the association had on the trophy.

The trophy was returned to the association and put up as a prize for the Swedish skiing competition. It was decided that the trophy should go to the district which had garnered the highest point total in all the competition runs over the past five years. Lia Jonsson, at that time head administrator of the association, suggested that the trophy be donated to the Swedish Ski Museum as a challenge cup for the 30 km Umespelen competition, which was intended to be a future international fixture. This suggestion, however, was ignored.

Nordeen (left) and Jakobsson (right) before the 1931 race.

Photo courtesy Hartell family.

In January 1961, Emil Nordeen wrote to Lia Jonsson to make some things clear regarding the donation. “I could not see myself as sole owner of the trophy. For that reason I could not see anyone else as having sole possession.” When the Ski Association’s decision became known to Nordeen, he wrote to his sister Emmy:

“What happened at Umeå in 1961 has remained a mystery to me until I received your letter. When I came home from Squaw Valley I wrote an additional provision [in the donor agreement] that if there were terms at odds with the Swedish Ski Association’s rules, then it was the responsibility of the Association to work it out. It was my wish that the Americans would have a chance to win the trophy back, but this was not binding. When I read between the lines, I wonder if it is not the rules, but something else that is in the way, and which I, nor you, have any knowledge of. In any event, I now have nothing to say regarding the trophy since it is not my personal property…If they do not wish to enter it as a challenge prize, then I think they should give it to Vasterbotten where it should be housed. I wish the Swedish Ski Association could have followed my directions, but it is also a possibility that my Swedish is so poor that they didn’t understand what I wrote…”

Nordeen and the association eventually reached an agreement, which allowed for the trophy to be the prize for a long ski race in Vasterbotten. The choice was Kalvtrasket’s run, one of Sweden’s oldest cross country races, near the area where Nordeen was born. It was agreed that the trophy should be lodged at the Swedish Ski Museum at Umeå between contests.

Trophy from a ski race in Oregon

The background to events at Umeå in 1961 began with the Winter Olympics in Squaw Valley in 1960. During the Olympics Swedish-American Emil Nordeen from Kvavistrask, Norsjo, contacted the Swedish Ski Association and donated a majestic trophy to be used as a prize for an annual international men’s competition. One of the conditions stipulated by Nordeen was that the race must be international so that American skiers could participate.

Nordeen near the finish. Photo courtesy Hartell family. |

Nordeen donated the Klamath Cup, which had been offered as a prize by the Crater Lake Ski Club beginning in 1929.1 It was the trophy recognizing the winner of a 70 km ski race between Fort Klamath and Crater Lake. The entire course was at high altitude, the first half of the race climbing close to 900 meters. In the event that anyone won the trophy twice, he would be allowed to keep it forever. The battle to be the first to win permanent possession of the trophy came down to two immigrants from Vasterbotten, Emil Nordeen and Manfred Jakobsson.2

Jakobsson was born at Högland, Nordmaling, in 1898. When he was seven years old, the family moved to Långed. Manfred worked in the timber industry at Norrbyskår until the winter of 1923, when he immigrated to southern California, where his sister already lived. After some time had passed, he went to McCloud in northern California, where he got a job in a lumber yard. His first experience with skiing competitions was in the early 1920s, when he won a ski race in Nordmaling.

Nordeen was born at Kvavistråsk in 1890. He had immigrated to America at age 18. For the next 20 years, his Swedish relatives received no word from him. When they finally made contact with him, Nordeen had spent much of his time in the Rocky Mountains. There he had hunted, fished, looked for gold, worked, and skied. In 1920 Nordeen settled in Bend, Oregon, where he found a job in a lumber mill.

The battle between Nordeen and Jakobsson

After four years in California without skiing, Jakobsson noticed a newspaper advertisement about a competition in Fort Klamath. With borrowed boots and nine foot skis that had poor bindings he traveled to Oregon, arriving about a week before the race. That year (1927) there was no trophy, but instead a prize of $250.00 to the winner, which at that time was worth about 1,200 Sw. kronor. The newspaper account of the race tells of the competition’s popularity, counting some 2,000 cars in Fort Klamath.3 Bets on the race were in the same style as in boxing, and included thousands of dollars. These were quite unthinkable circumstances in Swedish skiing at the time.

The first competition took place on President Washington’s birthday, February 22, 1927. Several thousand spectators came to watch Captain [O.C.] Applegate send off the poorly-equipped skiers. The first race took place under very difficult conditions. In Fort Klamath the grass protruded through the snow cover, and in some places there was water in the ski tracks. When the competitors got higher into the national park, there was heavy snow cover and a storm. In spite of this, Jakobsson won the race. Nordeen was among the other participants (who included a number of Swedes, Norwegians, and Finlanders) and had to make his own skis from ponderosa pine because none were for sale.

Jakobsson won again in 1928, but Nordeen was ahead for the first 55 km when ice built up under his new skis which he had ordered from Sweden. Nordeen won the Klamath Cup in 1929, the first year that the trophy was offered as a prize. Jakobsson, meanwhile, went home to buy a farm in Långed, where he eventually relocated when he returned to Sweden in 1932. During his visit in 1929, Jakobsson applied to race in the Vasa ski competition. His winning of the Fort Klamath competition and the $250.00 in prize money had been noticed in the Swedish press. Consequently, the Swedish Ski Association refused to let him compete at Vasa.

A weakened Jakobsson chasing Nordeen near the park’s south entrance.

Photo courtesy Hartell family.