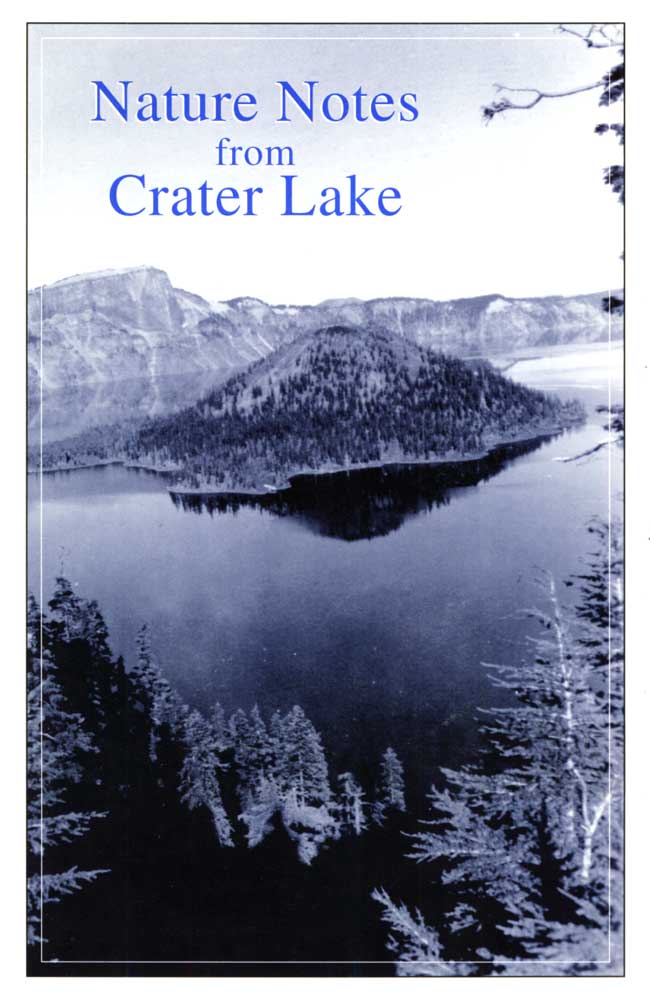

Volume 28, 1997

All material courtesy of the National Park Service. These publications can also be found at http://npshistory.com/

Nature Notes is produced by the National Park Service. © 1997

Introduction

The following articles might first appear to be beyond the scope of a publication calling itself “Nature Notes.” Yet what we choose to emphasize in studies or narratives about nature is conditioned by culture and shaped by our selective interaction with the past. How the past confronts the present at Crater Lake is the general theme of this volume, though the broader aim behind all issues of Nature Notes from Crater Lake is to add to the reader’s understanding and appreciation of the park.

Each of these submissions represents an attempt to clarify the past, so as to give it order and meaning in the present. The lead piece by Robert Winthrop emphasizes continuity in how one culture has seen Crater Lake through time by comparing this view with the European idea of sublime landscape. Loosley’s article is intended to reinforce what Winthrop presents as how the settlers saw the park a century ago. My article on the transportation route used to reach Rim Village at that time follows to demonstrate the roads and trails can have symbolic meaning. The device of repeat photography is described by Mastrogiuseppe and Salinas as an ongoing project under the sponsorship of the Crater Lake Natural History Association. On a somewhat different note, Lund’s overview of the Fort Klamath to Crater Lake ski races sets the stage for Astrom’s narrative about what resulted from one of those competitions. The last two pieces represent my attempt to put two features of the designed landscape at Park Headquarters into larger context.

The Crater Lake Natural History Association once again sponsors this edition of Nature Notes from Crater Lake, as part of its ongoing commitment to aid the education and resource management programs of the National Park Service. CLNHA encourages visitors and park employees to become members of the Association, and to join the Friends of Crater Lake National Park. A list of items available for sale can be obtained by writing to the Business Manager, Crater Lake Natural History Association, P.O. Box 157, Crater Lake OR 97604, or by calling (541)594-2211 ext. 499.

The reticent volcano keeps

His never slumbering plan;

Confided are his projects pink

To no precarious man.Emily Dickinson

Crater Lake in Indian Tradition: Sacred Landscapes and Cultural Survival

Introduction

Crater Lake and its environs served a range of uses for the Klamath, Upper Umpqua, and other Indian peoples of the region. The area of what is now Crater Lake National Park was used for both hunting and gathering. Huckleberry Mountain, an important gathering site for the Klamath, lies about ten miles southwest of the lake. Nonetheless, the primary significance of Crater Lake appears to have been as a place of power and peril, renowned as a spirit quest site, yet also feared for the dangerous beings residing in the lake. In short, Crater Lake constituted a sacred landscape, that is, a region distinguished in the traditions of a people by its special spiritual qualities or powers.1

The aim of this paper is to make such an alien reality somewhat more intelligible, both as a matter of cultural interest, and for its relevance to the sensitive management of this remarkable national park. I argue that there are, in fact, significant parallels as well as dramatic differences in Anglo-American and Indian perceptions of such sacred landscapes. Such a comparison can suggest both the degree of common concern for such geographies of refuge and transcendence, and what we as Anglo-Americans could usefully learn from the far more nuanced and complex appreciation of such landscapes inherent in Indian traditions.

Nature as sublime experience

Given the numerous controversies which have arisen since the 1970s over proposed development of lands viewed by Indian peoples as sacred or culturally sensitive, it is worth emphasizing that Anglo-American culture has also seen in nature an avenue for spiritual experience.2 The romantic movement, in particular, strongly influenced the perception of wilderness in nineteenth century America. Denis Cosgrove, in his interesting study of society and symbolic landscapes, noted that in America,

…by the 1820s and 1830s the idea of romantic landscape had invested scenes of wild grandeur with a special significance. They were held by many to be places which declared the great forces of nature, the hand of the creator…. In the context of a religious tradition which stressed individual salvation, the idea of sublime wilderness offered a powerful opportunity for transcendence, a way of appropriating America as a distinctive experience unavailable in Europe.3

Crater Lake, first encountered by Anglo-American travelers in the 1850s, admirably fulfilled the desire for a sublime and inspiring experience of nature. Captain Franklin Sprague, describing his visit in 1865, spoke of the lake’s “majestic beauties” and “awful grandeur.”4 Clarence Dutton remarked in 1886 on the emotional reaction which the lake aroused in its visitors:

It was touching to see the worthy but untutored people, who had ridden a hundred miles in freight-wagons to behold it, vainly striving to keep back tears as they poured forth their exclamations of wonder and joy akin to pain.5

John Wesley Powell, writing in 1888 in support of a bill to create a national park to protect Crater Lake, argued,

The lake itself is a unique object, as much so as Niagara, and the effect which it produces upon the mind of the beholder is at once powerful and enduring. There are probably not many natural objects in the world which impress the average spectator with so deep a sense of the beauty and majesty of nature.6

Similarly, Mark Daniels, former General Superintendent of the National Parks, said of Crater Lake:

The sight of it fills one with more conflicting emotions than any other scene with which I am familiar. It is at once weird, fascinating, enchanting, repellent, of exquisite beauty and at times terrifying in its austere-dignity [sic] and oppressing stillness.7

Enraptured by the sublime: a 19th century visitor at the rim.

Peter Britt photo, 1874. Southern Oregon Historical Society #704, Medford.

What is particularly intriguing about these expressions of geopiety to borrow a term from the geographer Yi-Fu Tuan — is the way in which they manifest both strong similarities and differences with the Indian experience of the Crater Lake region. The similarities lie in the common recognition of an encounter with the alien, the weird, and the numinous in this ancient caldera. Yet the differences are also telling. For the American explorers and settlers, the encounter with Crater Lake appears to have yielded a deep emotional response, but not a deeper knowledge or transformation of self. Such testimonies as these suggest an awareness of the sacred, but it is a mute awareness, a matter of mood. Unlike the Indian visitors to Crater Lake, the Anglo-American travelers lacked the cultural models — the cognitive templates encompassing mythology, ritual practices, and knowledge of localized spirit beings — which allow such encounters to yield a message, to produce lasting understanding and personal change.

This bafflement in the face of mute nature is captured well in a passage from the modern nature writer Edward Abbey. Of his travels in the American Southwest, he says,

I consider the tree, the lonely cloud, the sandstone bedrock on this part of the world and pray — in my fashion — for a vision of truth. I listen for signals from the sun, but that distant music is too high and pure for the human ear.8

Nature as sacred landscape

The Indian conception of Crater Lake was a matter of much comment by travelers and settlers of the region. The Portland Oregonian reported in 1886 that,

There is probably no point of interest in America that so completely overcomes the ordinary Indian with fear as Crater lake. From time immemorial no power has been strong enough to induce them to approach within sight of it. For a paltry sum they will engage to guide you thither, but before reaching the mountain top will leave you to proceed alone. To the savage mind it is clothed with a deep veil of mystery and is the abode of all manner of demons and unshapely monsters.9

Similarly, George Kirkman, writing in Harper’s Weekly in 1896, described the small island in the lake known as the Phantom Ship as “a fantastic object of unspeakable dread to the Klamath Indians.”10 These accounts, however exaggerated and in part factually incorrect, do convey a sense of Crater Lake and its environs as an area set apart, in some fashion fundamentally different in quality from the wider region, the southern Oregon Cascades.

For the Klamath, spirit power could be found in many sources.11 The spiritual significance of gi-was, or Crater Lake, reflected a more general Klamath understanding of the natural world, involving not only reverence but the possibility of significant interaction with particular mountains, lakes, and streams, as an individual sought comfort, assistance, or power.12 As one Klamath woman commented in the late 1940s:

…those old Indians had a lot of sense. They kind of felt at home around here and they would get a lift from just talking to the mountains and lakes. It was like praying and it made them feel at peace.13

In a sense features in a sacred landscape are persons: one can enter into relationships with them. A Klamath woman about 80 years old, paralyzed and bedridden, said:

Every day I pray to the mountain. I lie here in my bed and I am sick and old and every morning I say to those mountains, I say, “Bless me, help me.” I pray just like my mother taught me to do…. My mother taught me to pray to rocks and mountains and to give some food to them before we eat. It’s just like in the Bible. I dream of those mountains at night. They kind of help you when you ask it.14

The elements of a sacred landscape derive their power in part from a net of symbolic associations accruing from myth. Crater Lake figures prominently in the myth of Le*w and Sqel. Le*w is “the monster who dwells in Crater Lake …. rather octopoidal and of a dirty white color.”15 The myth relates his battle with Sqel (who also appears as Old Marten or Old Mink), a culture transformer in Klamath tradition, “teaching subsistence techniques, and generally preparing the world for the myth age humans.”16

The myth opens with Sqel/Mink/Old Marten and his friend Weasel. They are tricked by the beautiful but wicked daughter of Le*w, who ingratiates herself with Mink (or in an alternate version, Weasel), and tears out his heart. She then takes the heart to Le*w’s people at Crater Lake, who play ball with it. Weasel runs for help to Gmokamc, the Klamath creator figure, who advises Weasel, and then proceeds with the help of various allies to recover Mink’s heart. Mink revives, but Le*w now carries him off to Crater Lake, and is about to cut him to pieces and feed him to his children, the crawfish. However, Mink outwits Le*w and slays him, cutting up his body and (pretending the pieces belong to Mink’s own corpse) feeding them to the crawfish. Finally Mink throws Le*w’s head into Crater Lake, naming it correctly. In Theodore Stern’s translation of a version narrated by Herbert Nelson:

Then he [Mink] threw into the water all this, heart, windpipe-and-lungs, and liver. “Here’s Mink’s heart, windpipe-and-lungs, and liver!” Now the Crawfish came and ate all that. “Then here’s Lao’s [Le*w’s] head!” Bawak! sound of head splashing into the water. The Crawfish recognizing their father scattered in all directions. Then that head of Lao’s lodged there. This is Wizard Island.17

While Anglo-American travelers’ claims that Indians did not visit Crater Lake are false, the area was certainly regarded as the abode of powerful spirits. Traditionally, gaining a vision of such beings was a major goal of the spirit quest.18 The seeker would often swim at night, underwater, to encounter the spirits lurking in the depths of the lake.19Leslie Spier commented regarding the father of one of his informants, “having lost a child, he went swimming in Crater lake; before evening he had become a shaman.”20The quest for such spirits required courage and resolution:

He must not be frightened even if he sees something moving under the water. He prays before diving, ‘I want to be a shaman. Give me power. Catch me. I need the power.’21

One Klamath woman recounted seeing a spirit being on the lake:

When I was young, I went up to Crater Lake with a woman I knew. She tied my eyes and led my horse…. Then she said, “Untie your eyes,” and I nearly fell off the horse. I saw a man standing on the water far away, just like in the Bible. He scared me so, I don’t know who that was, but I like to think of that man now.22

Individuals undertook strenuous and dangerous climbs along the caldera wall. Some would run, starting at the western rim and running down the wall of the crater to the lake. One who could reach the lake without falling was thought to have superior spirit powers. Sometimes such quests were undertaken by groups. Rocks were often piled as feats of endurance and evidence of spiritual effort. Four of the five prehistoric sites thus far identified at the park are in fact piled rock sites. Here as elsewhere, such sites are usually built on peaks or ridges, with fine views. Leslie Spier reported one such named site built on a point of rock projecting from the western wall of the lake. Today Crater Lake remains important as a site for power quests and other spiritual pursuits, particularly for members of the Klamath Tribe.

Conclusions

To recapitulate: what has been termed here a sacred landscape entails a correlation of physical place and cultural meaning, existing within a larger body of tradition. Its physical elements (a piled rock site, Wizard Island, the lake bottom) have associations with various culturally postulated events, some in a mythic time, others occurring still today. Those who share traditional knowledge of a landscape such as Crater Lake bring to the encounter culturally patterned expectations which shape experience, form symbolic associations, and allow lasting experiential value to be gained.

Under such circumstances the tenacity with which many Indian tribes struggle to preserve their sacred landscapes is understandable, for such areas offer the possibility of sustaining tradition and identity, thus linking the future with the past. The attempt by Karok, Yurok, and other Northwest California peoples to preserve the “High Country” of Del Norte County from logging — the so-called G-O Road case, fought all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court — offers a recent example (see Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association, 485 U.S. 439 [1988]).

Within contemporary Anglo-American culture, there is evidence of a collective effort to discover or create such sacred landscapes. The ethos of sublime nature — which a century ago moved the “worthy but untutored” visitors to Crater Lake to tears — is apparently no longer sufficient. Today Anglo-Americans are rather ingenuously urged to seek out “sacred places” culled from the most diverse traditions.23 The acts of the more radical environmental movements (for example, those defending old growth forest); and the vague nature mysticism, coupled with imitation of things Indian, which suffuses many popular therapies — men’s groups taking to the woods to sharpen spears and chant — likewise seem directed toward fashioning sacred places within an increasingly disenchanted world. Whether it is culturally feasible deliberately to create ritual, myth, and sacred landscapes remains to be seen.

This paper has benefited significantly from the assistance of Gordon Bettles, Director of the Cultural Heritage Program, Klamath Tribe (Chiloquin, Oregon); and from Sue Shaffer, Chair of the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians (Canyonville, Oregon). Part of the material presented here is taken from a cultural resource overview of Crater Lake National Park, prepared for the National Park Service (Contract CX-9000-9-P013). Support by the NPS, and in particular James Thomson and Fred York of the Seattle Office, is gratefully acknowledged.

Notes

1 Regarding sacred space or sacred landscape, see chapter one in Mircea Eliade (Willard R. Trask, trans.), The Sacred and the Profane: the Nature of Religion (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1959); Linda Grabner, Wilderness as Sacred Space(Washington, DC: Association of American Geographers, 1976); Yi-Fu Tuan, Geopiety: A Theme in Man’s Attachment to Nature and to Place, in David Lowenthal and Martyn J. Bowden (eds.), Geographies of the Mind (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976); and Deward E. Walker, Jr., Protecting American Indian Sacred Geography, Northwest Anthropological Research Notes22 (1988), pp. 253-66.

2 Diane Brazen Gould, The First Amendment and the American Indian Religious Freedom Act: An Approach to Protecting Native American Religion, Iowa Law Review 11 (1986), pp. 869-91; Richard W. Stoffle and Michael J. Evans, Holistic Conservation and Cultural Triage: American Indian Perspectives on Cultural Resources, Human Organization 49(1990), pp. 91-99.

3 Cosgrove, Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape (Totowa, NJ: Barnes & Noble, 1984), p. 185.

4 Linda W. Greene, Historic Resource Study: Crater Lake National Park, Oregon(Denver: USDI-NPS, 1984), p. 271.

5 Harlan D. Unrau, Administrative History, Crater Lake National Park, Oregon (Denver: USDI-NPS, 1988), p. 32.

6 Ibid., p. 33.

7 Ibid., p. 233

8 Grabner, p. 44.

9 Green, p. 28.

10 Ibid., p. 29

11 Robert F. Spencer, Native Myth and Modern Religion among the Klamath Indians,Journal of American Folklore 65 (1952), pp. 217-26.

12 M.A.R. Barker, Klamath Directory, University of California Publications in Linguistics 31 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963), p. 145.

13 Spencer, p. 223.

14 Ibid., p. 222.

15 Barker, p. 215.

16 Ibid., p. 389.

17 Theodore Stem, trans., [Myth of] Crater Lake (Lao’s Daughter), narrated in Klamath by Herbert Nelson, 1951. MS on file at Crater Lake National Park.

18 Spencer, p. 222.

19 Leslie Spier, Klamath Ethnography, University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 30 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1930), p. 98.

20 Ibid., p. 96.

21 Ibid.

22 Spencer, p. 222.

Visited in Midwinter: A Trip to Crater Lake in 1897

Editor’s note: The following article represents the first recorded account of a winter visit to Crater Lake. It appeared in a Klamath Falls newspaper 100 years ago.

We left Fort Klamath on Tuesday, February 23, at 2:30 p.m. mounted on showshoes and drawing a hand-sled on which we packed our provisions and blankets and went that afternoon as far as Chas. Martin’s place at the upper end of the valley.2 That night the mercury went down to four above zero which made snowshoeing fine the next day, until we got within four miles of Bridge Creek, where the thermometer stood 45 degrees in the shade and 83 degrees in the sun, which temperature softened the snow to such an extent that it made shoeing impossible.3 We then ate our noonday lunch, put our shoes on the sled and footed it through the soft snow above our knees to Bridge Creek, where we arrived at 6 o’clock that evening, all tired out, having made only four miles that afternoon. After eating supper we made our bed down, or rather up, on fourteen feet of snow. Of course this was only a drift, as we did not have time that evening to look around for a shallower snow-bank upon which to make our bed.

Next morning we arose at daybreak, made breakfast and took the depth of the snow on the ledge across the creek, which we found to be only 8 and one-half feet deep. The thermometer registered that morning 28 above.4

Skiers going to Crater Lake from Fort Klamath in 1918. Photo by Alex Sparrow. |

Again we mounted our shoes and shoved our way slowly up Annie Creek Canyon, arriving at Cold Camp at 11:30 a.m., where we lunched and rested.5 We found the snow to be only 8 feet deep there. We had to abandon our shoes going up the summit and “take it afoot,” as the mountain was so steep that our shoes would slip back. However, we arrived on top at 1:20 p.m., and found the snow there to be 10 feet deep.6

When we got on the summit, instead of keeping [to] the road leading down on the other (north) side, we turned to the right and went along the backbone of the mountain which we thought would be a gradual slope all the way up to the lake and would avoid footing it down the mountain and crossing the swale and up the steep mountain again on the other side to the lake.7 But two miles of extremely difficult traveling along the steep backbone, through snow up to our waists, brought us to the conclusion that we had better abandon our roundabout trip and make our way down the mountain side to the camping place at the foot of Crater Lake Mountain, which we did, arriving in camp at 5:25 p.m. It would be useless to say that we were wet through to the waist and all tired out. However, we lost no time in getting a few slabs of thick fir bark upon which to build our fire by which we dried our clothing and cooked our supper.

Next morning, being the 26th, we left camp at 6 o’clock without breakfast, for the lake. Two miles up the steep mountain brought us to the brink of the most picturesque view which we were privileged to behold. There was the lake away down in the almost bottomless pit wrapped in the snowy gause of silence, while the gentle rays of the rising sun kissed the snowcapped peaks of the surrounding mountains as the gentle breeze rippled the inky water far below. There was a soft breeze blowing from the south, while the mercury stood at 38 in the shade and 76 in the sun.

There was a thick skim of ice on the west end of the lake extending eastward from the bank some two hundred yards and probably half a mile long north and south.

The snow under the trees on Mrs. Victor’s rock was five feet deep, while back farther in the open it was 10 feet, and seemed to be of an even depth all around the south side.8It was impossible to go down to the water as the snow which had blown from the south, broke off abruptly from the top for probably one hundred feet below when it would take its regular slant until within about the same distance from the water where it would again form another perpendicular bank. The water seemed to be as black as ink. We had a very strong glass with us, but we could not see any beach at the water’s edge.

Photo by Rudy Lueck, 1935. |

The snow was all off the trees on Wizard Island and surrounding bank, while the strip of land running out northwest from the island seemed to be a floating snowdrift.

We spent about an hour and a half at the lake when we turned our shoes homeward, where we arrived on the evening of the 27th.

No pen can describe the picturesque views we beheld on our trip. No orator could do justice to the mountain breeze, the crisp mild air and delightfully cool water bursting gleefully from the sides of the mountains. Now we are passing along one of nature’s wonderful creations — a canyon — where massive perpendicular rocks rise hundreds of feet on either hand. Again in open space, with massive peaks all about us, do we find ourselves. These nearest spurs are snow-capped and uninviting; those at a distance jagged and rugged.

The scenery at times partakes of weird and grotesque appearance, and is then grand and awful. Odd forms of snow, sometimes resembling mammoth animals, overhang our path or project from the mountain beyond and appear ready to leap upon us. Over all this magnificence, enhancing the picture to a marvelous degree, shone the azure vault above.

It is true we found places that were extremely difficult of traveling over, and yet how foolish we would have been to remain at home because of them. Deep gulches must be crossed, narrow and sliding ones were not infrequent. More than once did we hold our breath as we passed over some of these places, but a steady nerve and lots of energy were all that was necessary to carry us through.

Notes

1 Originally titled Visited in Midwinter: A Trip to Crater Lake Through Unfrozen Snow — A Difficult But Interesting Adventure. It was originally written as a letter to Captain O.C. Applegate and subsequently published as a newspaper article in March 1897.

2 The author was in the company of his brother, P. S. Loosley. Martin’s homestead was about 1.5 miles north of the town of Fort Klamath near what is presently Highway 62. The brothers would have gone approximately five miles that afternoon since the Loosley Ranch is located south of town.

3 This area is where the ponderosa pine and white fir forest gives way to lodgepole pine, a transition readily seen along the south entrance road. Bridge Creek is now called Pole Bridge Creek.

4 Much of the temperature difference between the two days was due to the downslope movement of air. This often makes the area around Fort Klamath (at 4200 feet in elevation) much colder than a site on Mount Mazama such as Pole Bridge Creek, some 1600 feet higher.

5 The vicinity of Annie Spring.

6 Their route corresponds to the trail which connects Annie Spring with the Pacific Crest Trail.

7 They tried traversing Munson Ridge instead of using the wagon route which roughly corresponds to what is now the Dutton Creek Trail.

8 Victor Rock is where the Sinnott Memorial is presently situated. The south side described by Loosley was named Rim Village in 1924.

Winter Illustration by L. Howard Crawford, Nature Notes from Crater Lake, 8:1, July 1935.

On an Old Road to Crater Lake

Oregon is a state where historic trails are of more than passing interest. Since one or more of them were crossed by the forebears of many current residents, these trails are more than a conceptual link with the past. Reenactments and other commemorative activities along the Oregon and Applegate trails, for example, have given associated wagon ruts, blazes, inscriptions, and campsites special status as symbols of hardy immigrants struggling to reach a promised land.

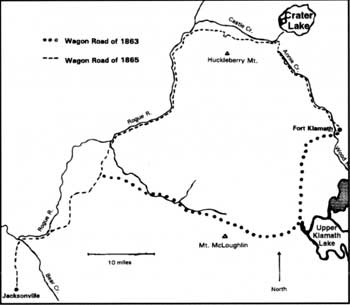

There are, of course, other types of 19th century trails in Oregon, ones that have little to do with a long treks toward a future home. Many of these carried stock or supplies, but were also used on outings by people seeking recreation and inspiration. One of them crossed Oregon’s only national park and has largely escaped widespread notice. It was constructed in 1865, after the U.S. Army recognized a need for better access between its post at Fort Klamath and supply points such as Jacksonville in the Rogue River Valley.

Map by Steve Mark. |

Although a track around Mount McLoughlin had been built at the time of the fort’s establishment in 1863, that road proved to be steep and difficult.1 Consequently, a company of soldiers commanded by Captain F.B. Sprague found a route in the summer of 1865 which made crossing the mountains considerably easier. Much as Highway 62 presently does, the route stayed above and west of Annie Creek Canyon and found a relatively easy crossing of the Cascade Divide at an elevation of 6,300 feet. From there they began a descent, avoiding Castle Creek Canyon by staying south of it, and in 20 miles or so reached the Rogue River near what is now the settlement of Union Creek.

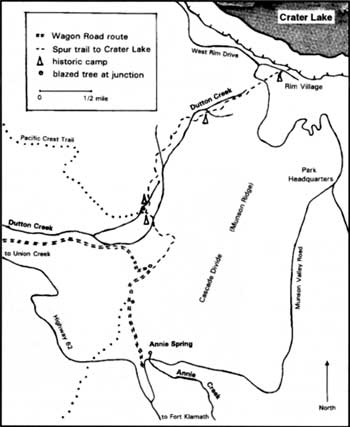

The soldiers saw Crater Lake and several of them wrote about its wonders in newspaper accounts, but the new road came no closer than two miles from the rim. It was left to a tourist party formed in Jacksonville during the summer of 1869 to blaze a track from the Army’s wagon road to the area now known as Rim Village.2 They went up Dutton Creek rather than Munson Valley (where the road connecting Rim Village with Highway 62 currently runs) until 1905 because the upper end of the latter was difficult to traverse without improvement by heavy equipment.

19th century visitors sometimes left carvings on trees near their camp. Photo by Steve Mark. |

Establishment of Crater Lake National Park in 1902 eventually paved the way for a series of road improvements. Part of the wagon road was overlaid with asphalt or chopped into segments by realignments and eventual widening of Highway 62. Despite the changes, portions of it remain. The wagon road can be seen in places as a narrow depression, while in others naturally seeded trees have filled the compacted bed. Blazes are still apparent on living trees or snags and are sometimes used to find the old alignment where ruts or depressions are absent.

Approximately four miles of the first road to lead visitors to Crater Lake are fairly evident on a hike which begins at Annie Spring. A tell-tale depression quickly becomes evident on the downhill side of a more recently constructed hiking trail which climbs toward the divide. Some ruts can be seen from the hiking trail just above the water tank. Close inspection of the adjacent trees reveals that blazes have healed after more than a century, but so- called “cat faces” can be seen at eye level. Hatchets long ago left hack marks on several trees at the divide, where the hiking trail followed from Annie Spring merges with the Pacific Crest Trail. From this point it is another mile or so to the next trail junction where the Dutton Creek Trail begins.

The intervening distance will reward a sharp-eyed hiker looking for evidence of the wagon road. Upon descending roughly one half mile from the divide, a large snag to the left can be seen. A triangular cat face on it indicates where the wagon road diverges from the trail to Crater Lake that was first blazed in 1869.3 A few hundred yards further on, the hiking trail crosses several streams which feed upper Castle Creek. This area once served as an informal camp, and there are at least two places where blazes are accompanied by tree carvings with names of early visitors. More important for botanists and others interested in saving rare plants, this is where a member of the phlox family with small purple flowers was discovered in 1896. The camp area has thus become the type locality for Collomia mazama, and populations there continue to be an important reference point for scientists studying the plant’s life history and reproductive biology.

Map by Steve Mark. |

Much of the modern Dutton Creek Trail closely corresponds with the track first blazed in 1869. Blazes on Mountain hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana) and Shasta red fir(Abies magnifica-procera) indicate where several subsequent realignments of the trail occasionally diverge from the original route.4 Roughly three-quarters of the way (1.5 miles) up this trail is another camp. It is located behind a “Closed for Restoration” sign and contains several tree carvings. This site was described in an 1885 account because it represented the closest that campers could get to the rim and still have water readily at hand. From there visitors to Crater Lake would climb another 400 feet over the next mile to reach the high but dry camp sites at what is now a picnic area in Rim Village. The original trail can still be followed between these two points, but careful observation is needed to find the route once it diverges from the upper portion of the modern Dutton Creek Trail. Blazes are still evident at the northwest corner of the picnic area and tree carvings can be seen within a few paces of the Rim Visitor Center. Both furnish silent testimony that the rim attracted people even before facilities were in place to accommodate visitors with automobiles.

The development which has so altered the face of Rim Village is a reminder of how the park’s visitation has changed in the past 100 years. Several thousand people per year came to Crater Lake in the 1890s, but the annual figure is now around a half million. Perhaps more significantly, the average length of visit to the park is considerably different. Whereas the majority of people today spend less than four hours in the park (and far fewer still are here longer than one night), 19th century visitors might spend a week at Crater Lake. They often combined their visit with gathering huckleberries(Vaccinum membranaceum) at Huckleberry Mountain, located just 10 miles southwest of the lake. The wagon road made both places more accessible to white settlers and Klamath Indians, who could afford a respite from the more burdensome aspects of life.5

Travel to Crater Lake has changed a great deal since then, particularly after 1908 when automobiles were allowed in the park. What remains of the wagon road is still important, however, to understanding and appreciating what people once experienced on their journey. Despite being bracketed by modern developments, it can still convey change and continuity to those visitors who seek to better comprehend the past.

An old camp on Dutton Creek. Photo by Steve Mark.

Notes

1 This trail has been marked in several places with commemorative signboards. Perhaps the best preserved stretch is the Sky Lakes Wilderness along what is now known as the Twin Ponds Trail.

2 Led by news editor James Sutton, this group brought the first boat to the lake and used it to explore Wizard Island. They also gave Crater Lake the name by which it is still known.

3 Although the wagon road is heavily eroded in steeper sections and filled with small trees in others, it can be followed to where it crosses Highway 62 about a half mile east of Whitehorse Creek.

4 The relatively short life span of 80 to 120 years for lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta)generally precludes finding blazes on this species, especially since the practice was discouraged after the national park was established.

5 Park founder Will G. Steel recalled seeing more than 200 Klamath encamped near the rim in August 1896. This took place while a considerable number of whites also camped around Crater Lake.

Other pages in this section