Future work

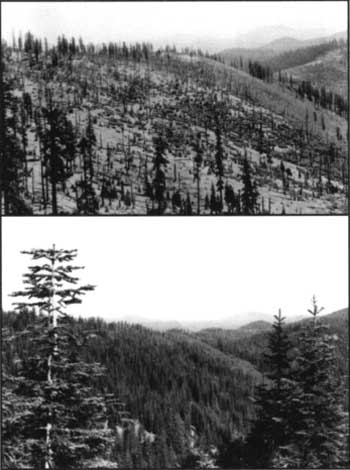

Each person and every piece of equipment can be severely tested in this harsh environment. As the fallen mast of the Phantom Ship was being photographed from a tour boat making its rounds last summer, Salinas noticed an odd sound to the shutter on his large format (4 by 5 inch) camera. The shutter seemed to be hanging up after a cold night in the park. As it turned out, the same shutter failed to capture a dozen photographs around the lake and some from the top of Mount Scott. These photographs will have to be retaken during the summer of 1997 since the 1996 season ended without obtaining a complete set of repeat images. The project’s goal is to display copies of the original and repeat photographs in park exhibits and throughout a number of buildings. We hope this first attempt at repeat photography will lead to another project which will produce a book of large black and white paired photographs in time for the centennial of Crater Lake National Park in 2002.

The authors would like to acknowledge the Crater Lake Natural History Association’s sponsorship of this and other endeavors. The repeat photography project would not have been possible without discovery of the Diller photos by former seasonal interpreter Mike Smith and the assistance provided by USGS librarians in Denver.

History of the Crater Lake Wilderness Ski Race

The Crater Lake Wilderness Race between Fort Klamath and Crater Lake Lodge was held annually from 1927 to 1938. The grueling race, originally 42 miles long, gained over 2,800 feet in elevation and challenged skiers with varying snow conditions. The race was shortened to 32 miles in 1932, five miles in 1936, and by about 1938 both the race and the accompanying winter carnival were discontinued. In 1978, the race was revived by the Alla Mage Skiers and Crater Lake National Park and now attracts about 100 skiers annually.

The “Carnival” included snow balling, toboganning, sleighing, short races for high school students and adults, as well as ski jumping (the record jump was 151 feet), sled dog races, barefoot races and a homing pigeon race. There was usually an all-day dance in the community hall.1 The Carnival and the historic race attracted as many as 4,000 spectators.

In the early years, a 16-mile race from the Rim to Fort Klamath was the “down mountain” or “trail breaker” race for the longer race; but later, the “down mountain” race was the more popular.

In 1927, a total of 24 skiers entered the race. The course followed the Crater Lake Highway to the Lodge and back, with contestants required to keep within one half mile of this course. Any style, make, pattern or length of ski and harness could be used; however, metal skies were barred. Manfred Jacobson, “a sandy haired logger” from McCloud, California, and Waldemar Nordquist, “a powerful lumber piler” from Klamath Falls, fought for first place. Jacobson had a peculiar “slide-slide and then skip technique like a skating stroke – his entire body swinging to the rhythm of the forward lunge.” Nordquist, a former Swedish Army Captain, used arms and ski sticks more. The Klamath Falls Evening Herald reported that the two Swedes were “…engaged in one of the greatest battles of endurance, of wits and of the elements in the history of the Pacific Coast.” New snow made the going “tough and hard,” but the two men arrived at the lodge together. Jacobson had let Nordquist pass him on the way to the rim, requiring him to break trail and use precious energy. Returning downhill, Jacobson lost a ski and Nordquist a ski stick. The lead changed when they stopped to retrieve the equipment. Jacobson crossed the finish after 7 hours and 34 minutes, to win the first prize of $250. Nordquist, 21 minutes behind, won the $100 second prize. Nels Skjersaa of Bend and Everett Puckett of Klamath Falls battled for third place. Skjersaa claimed the $50 prize, and Puckett won a radio set. Harry C. Francis of Klamath Falls was fifth, winning a rifle, and Otto Hagen of Brightwood and Andy Versto of Fort Klamath tied for sixth place.

The 1927 race brought huge crowds to Fort Klamath.

Photo courtesy Klamath County Museum.

The second race had 16 entrants: “…stalwart athletes, most of whom bear names reminiscent of the snow-clad mountains of northern Europe.” Twelve of the racers dropped out, “…unable to keep pace with the quartet of northlanders: Manfred Jacobson, Nels Skjersaa, Waldemar Nordquist and Emil Nordeen of Bend.” Jacobson won the race for a second time, in 6 hours and 13 minutes. Emil Nordeen was eight minutes behind.

In 1929, Emil Nordeen, “the crafty ‘Old War Horse’ of Bend,” won the race in a record time of 5 hours 57 minutes. At 43 years, he was the oldest as well as the fastest skier. Skjersaa was second and 28 minutes behind Nordeen. Emil was awarded the solid silver “Klamath Cup” which stood 38 inches high and was trimmed with gold. The winner kept the cup only one year, but Nordeen could keep a smaller 6-inch high cup called the “Shadow of Klamath.”

Manfred Jacobson won in 1930, with a time of 7 hours, 40 minutes and 30 seconds. Nordeen was 34 seconds behind Jacobson and Skjersaa placed third. The other two entrants, Nordquist and Oliver Puckett of Keno, dropped out. The racers had to battle two feet of new snow in the park but were forced to make a five-mile loop at the finish because there was virtually no snow at Fort Klamath.

In 1931, there were four entrants, but only two finished. Nordeen, who came close to not entering the race because of an injury, broke the record at 5 hours and 35 minutes. Jacobson placed second. Ivar Amoth of Bend broke a ski and Oliver Puckett dropped out after 34 miles. Nordeen had now won the Klamath Cup for the second time, and thus gained permanent possession of it (see the article by Kenneth Åström). The Skyliner Skiing Club members of Bend carried Nordeen on their shoulders to the community hall. The newspaper reported 848 cars parked on the grounds.

In 1932 the race was shortened to 32 miles, but a new ski jump was inaugurated and buses brought spectators to the events.2 A record 4,000 people attended the Snow Show. This was the sixth year that Oliver Puckett had entered the long race, and with his lucky rabbit’s foot, he finally won in 4 hours and 26 minutes. He was the first native born American to win the race. Pete O. Hedberg of Modoc Point was 30 minutes behind, while Rudy Lueck, a park ranger at Crater Lake, was third.

Hedberg was the other two-time winner of the races. Another Swede by lineage, he won the race held in 1933. After poor snowfall canceled the race in 1934, Hedberg retired the second Klamath Cup with a win in 1935. During that race he was operating under a slight handicap; he had broken his leg several months earlier and the cast was removed only three weeks before the competition.

Oliver Puckett almost won in 1933, but Pete Hedberg passed him in the last mile. Puckett won the second place trophy, called “the Watchman.” Rudy Lueck was once again third. Hedberg’s winning time was 4 hours and 30 minutes, four minutes ahead of Puckett. Rudy Lueck was only a few yards behind Hedberg in the 1935 race, with Harold Paulson of Bend third to complete a “horse race finish.” Puckett led the racers to the rim, but then dropped behind on the return.

After the 1935 race, the Evening Herald reported that “Skiers and officials of the Crater Lake Ski Club and Klamath Winter Sports Association are inclined strongly to the opinion that the long race is too tough, and now that Hedberg, by virtue of his two victories, has won the cup, the event might as well be dropped from the Klamath winter sports program.” The race was thereby shortened to five miles in 1936 and 1937. Frank Drew of Klamath Falls and Delbert Denton of Fort Klamath were the winners these two years. A race of only one mile in length was held at the rim of Crater Lake in 1938.

Other than the sometimes dramatic finish of the men’s race, this event had many highlights. Myrtle Copeland of Fort Klamath entered the 1927 race with an unusual handicap; she forgot her boots and had to ski in house slippers. Needless to say she did not win, but nine years later she won the five-mile race. The Briscoe sisters of Fort Klamath often entered and won the shorter women’s race. Ida, Vinnie and Peggie Briscoe also won the relay race in 1933. The Drew family of Klamath Falls also had winners in many of the shorter races. Frank and Greer often competed for first and second place in the high school and college student races. Lester Hellens of Seattle and Millard Briscoe of Wood River won the first two “down mountain” races.