A National Historic Landmark

At the top of a steep and winding road which leads from the plaza at Park Headquarters is the Superintendent’s Residence. It has a commanding view of Castle Crest (sometimes called Garfield Ridge) and the backdrop of a subalpine forest which can provide a sense of deep seclusion. This location attracts few visitors, except for those occasions where park staff lead walking tours to this and other contributing structures in the Munson Valley Historic District.

In 1986, the National Park Service conducted a theme study to find the best architectural examples in the whole National Park System. The structures chosen would be designated national historic landmarks by the Secretary of the Interior. This is in accordance with a program which since 1935 has recognized the sites, structures, and landscapes most significant in American history. The Superintendent’s Residence thus became one of only 50 or so buildings recognized in this way, largely because its character-defining features are intact and compelling enough to warrant further inspection when sighted even from a distance.

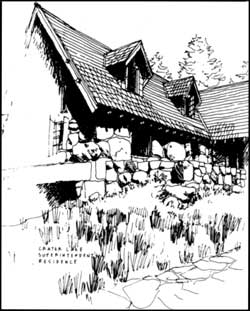

NPS drawing, Denver Service Center. |

Massive andesite boulders, even larger than those elsewhere in the district, are probably the most noticeable feature of the house. They were gathered from a site next to the Rim Drive below the Watchman, and then brought by trucks to the building site. Once there, a homemade hoist and a crew of laborers lifted the boulders into place under the direction of an Italian stonemason named Joe Mancini.1 The largest ones can be seen on the east side of the building, yet they seem perfectly scaled because of being surrounding by undressed and uncoursed stone of complementary size, color, shape, and texture.

In walking around the residence, observers will notice that the four sides are different from each other. This is partly due to the building being asymmetrical, but a mix of peak and shed dormers add variety to the roofline, as does the top of a massive stone fireplace that was specially built by Mancini. The shakes are stained green, and were cut from sugar pine logs originating in the Prospect vicinity. Second story siding and trim are a chocolate brown color and were meant to imitate the surrounding forest, while the brushed concrete slab over the garage resembles a ledge or an exposed bedding plane.

Just as in nature, the genius of this type of architecture is in the details. Multi-paned casement windows open to the outdoors, and are inset from the rock walls to give each facade texture. Even more subtle is how National Park Service designers used the shade of surrounding trees and shadows cast by the structure’s details to create different lighting effects depending on the time of day.2 The heavy plank front door is embellished by strap hinges and decorative ironwork, wrought so as to convey some sense of the past and replete with pioneer and even medieval allusions. These and interior features such as wagon wheel chandeliers, wall sconces, and gothic diamond designs in woodwork or stone are intended to evoke emblematic associations in those who acknowledge that life has layers of meaning subject to individual interpretation.

It may seem odd that this structure, which is seen so rarely by visitors, became a national historic landmark while the Crater Lake Lodge went unrecognized except for a brief and rather hesitant listing on the National Register of Historic Places. There are two compelling reasons for this. The first is that the Superintendent’s Residence retains virtually all of its original material (called “historic fabric” by preservationists), in contrast to the lodge where a multi-million dollar “rehabilitation” left it with less than ten percent of what was there before 1991, when the facelift started. Consequently, about the only thing preserved in place after four years of construction was the hotel’s proximity to Crater Lake. It is that association with the main feature in the park which makes the lodge an unforgettable attraction to some visitors, so much so that they overlook being in a new building made to appear old.

The Superintendent’s Residence does not rely on Crater Lake to achieve its visual effect. It is almost 500 feet below the rim and sited to appear as part of the setting, which constitutes the second reason for NHL status. When the house was completed in 1933, it needed very little landscaping other than a small amount of foundation planting to make an even transition from ground to structure. The idea of making it seem to have “grown from the ground” is inherent in sloping, not straight, walls where masons situated the largest boulders near ground level as in nature. Crater Lake Lodge, by comparison, was a landscape architect’s nightmare. Not only did the hotel impose its form on the lake, there were few ways that a four story structure could be integrated with the surroundings. For one thing, an undercapitalized concessioner had taken what was essentially a suburban estate house of 1908 and then omitted a number of details so the unfinished hotel could be opened for business in 1915. A large addition more than doubled its size by 1924, but almost nothing in the way of landscaping took place until 1931. Even then, the NPS had to transplant large trees and shrubs in a desperate attempt to soften the square lines of a huge building which dominates the eastern half of Rim Village.3

Front entrance of Superintendent’s Residence. Note large boulder near door. Photo by Laura Soulliere, 1986. |

Perhaps the single greatest tribute paid to the Superintendent’s Residence came in 1990, when a Colorado-based publisher sought to reprint a NPS guidebook to park and recreation structures which last appeared in 1938. The late ‘thirties were a time when Congress authorized the NPS to help develop state and local park systems as part of work relief projects undertaken by the Civilian Conservation Corps. A guidebook was needed to assist newly-hired landscape architects with design challenges stemming from having to integrate facilities with different park settings. Some 50 years hence, architects and landscape architects had begun to rediscover designing with nature and become so interested in making structures fit their setting that the publisher decided there was a market for a reprint of Park and Recreation Structures. Only one image represented the reprint (which sold quickly and enjoyed more than passing notice) in his catalog and on the jacket cover. It was, of course, a photograph of the Superintendent’s Residence on a clear June morning, just after it had been reopened as seasonal housing for yet another summer.

Notes

1 Mancini and his crew of masons worked at Crater Lake from 1930 to 1938. They were responsible for most of the building facades which incorporate large boulders, as well as fountains, parapet walls, and other features.

2 Although the building plans bore one set of initials (A.P.B. for A. Paul Brown), NPS structures during this period were really the product of consensus among a team of architects and landscape architects who designed and often supervised the work. They would insist upon relatively uniform standards in design and could adapt construction to fit the site, all without having to contract the part or all of the project.

3 Perhaps the most successful part of the planting program was the circulation features used to distribute guest parking and soften the building’s mass when viewed from the south. Transplanted mountain ash, along with stone steps and curbing, helped to lessen the visual imposition of the lodge on its surroundings.