An Offering in the Forest

Winter can last for more than seven months at Park Headquarters. A sign of the coming of spring appears when enough snow has melted to reveal a figure known as the Lady of the Woods. When the snow finally disappears, which is usually in June or July, visitors can take a short trail located behind the Steel Information Center to view the three foot high sculpture. Chiseled from a boulder, this unfinished work of art blends almost perfectly into a subalpine forest of mountain hemlock. It will be 80 years old this October and shows a few signs of age. The most noticeable is pitting in the once smooth volcanic rock, but there are also some details that have begun to fade with time. In spite of its inevitable decay, the sculpture is still striking and should remain recognizable well into the next century.

Oddly enough, the Lady of the Woods was its creator’s first attempt at sculpture. At the time of its carving, Earl Russell Bush was a 31 year old medical doctor who attended to the road crews that built the first rim drive around Crater Lake. The season’s work had largely ceased by the end of September 1917, and he found himself with almost two weeks at his disposal. Bush left the park on October 20th, having chisled and hammered a recognizable form on the hard rock. He worked from memory and, several years later, tried to explain what possessed him:

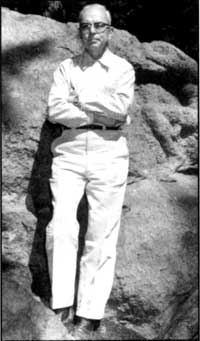

Earl Russell Bush and the Lady of the Woods, 1954. NPS photo by C. Warren Fairbanks. |

“This statue represents my offering to the forest, my interpretation of its awful stillness and repose, its beauty, fascination, and unseen life. A deep love of this virgin wilderness has fastened itself upon me and remains today. It seemed that I must leave something behind…if it arouses thought in those who see it, I shall be amply repaid. I shall be satisfied to leave my feeble attempt at sculptural expression alone and unmarked, for those who happen to see it and who may find food for thought along the lines [of what] it arouses in them individually. It would be sacrilege to assign a title and decorate it with a brass plate. “

By the 1930s the statue acquired both a title (suggested by Fred Kiser, the photographer, who seemed to always be looking for different ways to promote the park) and a sign made of wood with raised lettering. The idea of leading visitors there with a trail came under attack for the first time in 1930, and is an objection which has been voiced several times since then. Not by visitors, nor through conservation groups, but by park employees who thought the sculpture did not belong in a “natural” area. To them, such artifice had no place even at Park Headquarters, where rustic architecture and naturalistic landscape design blend aesthetics with function. Just as with stone masonry (which is used on buildings and evident in walls, steps, curbs and even drainage features), the carving constitutes an attempt to design with nature. The only difference is that the sculpture’s functional aspects may not be immediately apparent to all who view it.

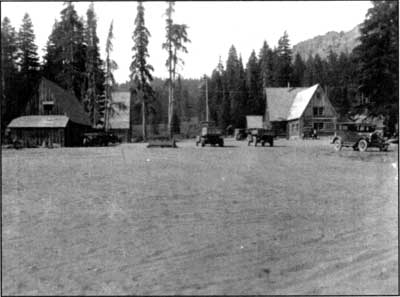

Whereas the function of most built features at Park Headquarters has been put in terms of visitor services (information, restrooms) or support facilities (employee housing, offices, equipment storage), the Lady of the Woods serves to instruct and inspire. The sculpture can speak to change, because 80 years ago Park Headquarters looked considerably different than it does today. When Bush made his carving in 1917, there were only three log buildings and a barn with no attempt at year round occupancy of the site. Less than a decade later the National Park Service began building a headquarters where the road camp had been, something which expanded over time to impinge on the sanctity of the forest that Bush once knew.

The Lady of the Woods is not, however, a merely antiquarian artifact (where the past is separated from the present) because NPS landscape architects incorporated it within an exceptionally coherent site design, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1988 as the Munson Valley Historic District. Despite the recognition, designed landscapes cannot be frozen in time and compromises remain apparent — most notably in the NPS having to utilize Park Headquarters for winter operations. This can be seen even along the 400 foot trail to the Lady of the Woods. Not only have the Messhall and Meathouse been adaptively reused (for ranger operations and a trail cache, respectively), but looming in the distance between them is the recently constructed maintenance shop — an especially unartistic and slavish example of form following function when contending with snowfall.

Park headquarters at the time when Bush carved the Lady of the Woods, ca. 1925.

NPS photo.

While change is important, character-defining features of the historic district and (in particular the Lady of the Woods) are more significant as representations of continuity. This type of continuity pertains to how parks evolved as a cultural expression of interaction with a certain setting or environment. Parks began as simple enclosures, intended as places where the nobility exercised exclusive rights to hunt game animals. During the 17th and 18th centuries parks fused with ornamental gardens, the latter having originated in the Ancient World from an urge to manipulate nature and create pleasing effects. Features of the garden (such as plantings which imitated growth in the wild, walks, and statuary or other structures built to evoke introspection in those allowed access) followed Classical models at first and then became more “natural” as the desire to emulate landscape paintings spread throughout western Europe. The English were especially adept at creating “landscape gardens” and developed a vocabulary for enjoying the “picturesque” surroundings which were contrived to appear more natural than Nature itself. When parks became public as a response to 19th century urbanization resulting from the Industrial Revolution, the private landscape gardens of the gentry and a newly rich class of merchants thus became models for how to socialize a broad spectrum of citizens by bringing them into contact with the perceived benefits of nature.

Those familiar with the landscaped parks brought their vocabulary with them when they went looking for “sublime” scenery. These people followed their guidebooks and found monumental scenery which matched the lighting effects employed by landscape painters to animate mountains, forests, lakes, waterfalls, caves, or coastlines. Americans embraced these aesthetic tastes at roughly the same time as the public park movement came across the Atlantic. It is therefore no surprise that public parks could encompass not only the countryside within or adjacent to cities, but also the most sublime scenery, particularly where the land remained in the Public Domain. National parks are really part of a vast national estate, where a few of the most unusual features such as Crater Lake can be protected for future generations to contemplate. By seeing sublime landscapes as art, the prevailing taste allowed for access but sought to minimize visitor impact.

Consequently, developments in the national parks have usually had both functional and ornamental qualities, with the best being subordinate and inspired by its surroundings.

Employees and visitors are now prevented by NPS regulations from making artistic statements similar to Bush’s, but the Lady of the Woods is a rare window into the cultural patterns behind the origin and use of national parks. Through this sculpture and rustic architecture elsewhere in the park, it is possible to relate the story of how a collective perception of nature developed through time and found expression in gardens, parks, and finally sublime landscapes. I thought of this inheritance and Bush’s intent when these lines from J.M. Synge’s Prelude came to mind:

I knew the stars, the flowers, and the birds,

The grey and wintry sides of many glens,

And did but half remember human words,

In converse with the mountains, moors, and fens.

Reference: Richard M. Brown, The Lady of the Woods Revisited, Nature Notes from Crater Lake 21 (1995), pp. 5-12.

Karl J. Belser, in Ernest G. Moll, Blue Interval (Portland: Metropolitan Press, 1935)

Rock Patterns

(The Grottos)

Out of the ancient rage of fire and frost

And prisoned forces struggling to be free

Came beauty such as poets, vision-lost,

Dreamed long ago in dales of Arcady.

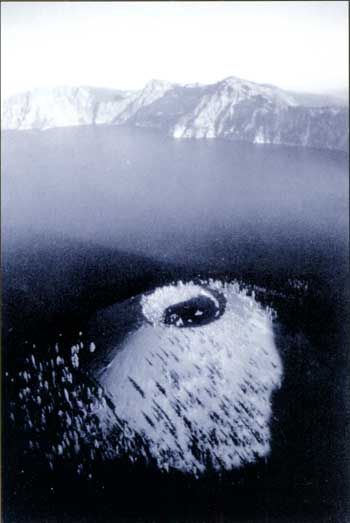

The crater on Wizard Island and Crater Lake.

23 James A. Swan, Sacred Places: How the Living Earth Seeks Our Friendship (Santa Fe, NM: Bear & Co., 1990).

***previous***