Williams Crater is roughly between 22,000 and 30,000 years old, and is located about one kilometer west of Hillman Peak. It is a basaltic cone that is aligned on a fissure (a linear crack in the earth’s crust) that is radiating outward from the rim. Unlike any other cones in the park, there are bands and inclusions of intermediate and silicic pieces in the basaltic lavas and the volcanic bombs that surround the cone of Williams Crater. These pieces of higher silica lava were most likely entrapped in the magma as blobs and crystal mush prior to being erupted from the basaltic cone. Some high silica magma was eventually made in the chamber and began to separate from the mafic magmas. The higher silica lava found its way up this particular vent to the west and was erupted as entrapments or inclusions in the basalt, due to this cone being close enough to Mount Mazama, Other cinder cones in the park, such as Crater Peak and Red Cone for example, were too far away from the growing chamber for this to occur. The Williams Crater complex, in other words, shows that there was some development of differentiated magma compositions in the chamber beneath Mount Mazama at least 30,000 years ago. It is uncertain whether these inclusions offer sufficient evidence of a bimodal system extending that far back in time, but they do give us some information about when this separation may have begun to take place. Many geologists believe that separation between these compositions continues into the present, but it is also worth asking about the characteristics of volcanic activity since the climactic eruption.

On the bottom of Crater Lake, the Dacite Dome to the east of Wizard Island is made of high silica dacite. Prior to its eruption, however, the formation of Merriam Cone took place just south of Cleetwood Cove from lower silica basaltic-andesite. Once again, two different compositions in the same general vicinity. This contrast beneath the lake is not really enough evidence to conclude that the Crater Lake volcanic system is still bimodal, but samples around the park appear to suggest it still has that capability.

Brandon Browne served as a volunteer-in-parks during 1997 and is presently studying geology at Oregon State University in Corvallis.

Example of “spheroidal weathering” along the Garfield Peak Trail, Nature Notes from Crater Lake, 7:2, August 1934.

Victor Rock and Victor View

Throughout the summer a number of visitors come to the information desk at Park Headquarters asking about the best place to see Crater Lake. These people have convinced themselves that they have only an hour or so to spare in the park, and then want to be on their way to somewhere else. I routinely dodge this type of query, if only because they have not yet seen the lake. This makes it impossible to communicate where around the rim a person could best appreciate that wonderful combination of color, geological features, and subalpine vegetation which has prompted more than one person to describe Crater Lake as the most beautiful thing they have ever seen in nature.

For those who are so short on time, and wish to limit their experience to one which involves little or no contemplation, any lake viewpoint between Park Headquarters and the North Junction will do. Motorists soon find that more than one stopping point allows them to stay in their vehicle and still see Crater Lake. They will, however, find it difficult to appreciate their surroundings without a good guidebook at the very least.

The Mazamas, a mountaineering club based in Portland, published the first booklet aimed at enhancing visitor enjoyment of Crater Lake in 1897. It had limited availability, so the government began to print pamphlets and maps with some explanation of the park’s geology. These devices still fell short, it seemed, of allowing the non-scientist to fully comprehend what lay before them. Trained naturalists began lecturing and guiding the public in Crater Lake National Park during the summer of 1926, but the question of how to best convey the park story remained. After some study, park officials decided to focus most of their educational program at Rim Village because of its proximity to what had long been the most popular viewpoint at Crater Lake.

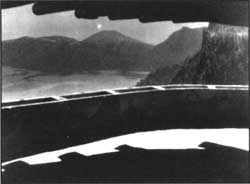

Visitor near Victor View in the late 1930s.

Named in honor of a historian who visited the lake in 1872, Victor Rock appears to be precariously perched some 900 feet above the water. The Sinnott Memorial was situated over this viewpoint in 1930, so that naturalists might give a brief orientation talk from an open-air parapet on a regular basis throughout the summer. Certainly no classroom, nor any other facility situated away from the rim, can equal the Sinnott Memorial as a venue to both see and hear about Crater Lake for the first time. It continues to function as an observation station aimed at enticing visitors to explore the park, in the hope that what they experience here will fuel an ongoing fascination with the forces which continue to shape the earth.

The sinnott memorial’s parapet as it appeared iin 1933. NPS photo by George Grant. |

To broaden the introduction given by naturalists in the Sinnott Memorial, park officials initiated an educational boat tour of Crater Lake in 1931. That year they also began a project which was to widen and realign Rim Drive. In addition to making the road safer, designers focused on showing motorists many important park features. In order to accomplish both goals, masonry walls and the resulting series of observation stations were built to blend into their surroundings. Just as the Sinnott Memorial is virtually invisible from the surface of Crater Lake, the Rim Drive is intended to facilitate contemplation of the lake, cliffs, and forest by minimizing road scars that can be seen at a distance. Far from being the cookie cutter pull outs which often characterize modern road design, each of the observation stations was intended to help visitors see the park in different ways — as anyone who has been to such divergent stops as Discovery Point, Grotto Cove, Skell Head, and Kerr Notch will attest.

The East Rim Drive in particular remains much as its designers left it, while also being largely free of the noise and crowds which often dominate the through route from Rim Village to the North Junction. With the notable exception of the Cleetwood Cove parking area (where people have gathered almost every summer day since 1960 for hikes down to the lake and a boat tour), visitors who pause along this 24 mile road segment should have few distractions — especially if they are inclined to walk even a short distance. In nominating a favorite stop along this stretch of road, my choice is based on the following subjective combination of factors. These include the predominance of quiet, an opportunity to hike, the attractive contrast of subalpine vegetation with open slopes, authentic examples of stone masonry from the 1930s (original work can be identified from mortar joints which feature some lichen growing on them), and, of course, the sublime drama of Crater Lake.