Volume 30, 1999

All material courtesy of the National Park Service. These publications can also be found at http://npshistory.com/

Nature Notes is produced by the National Park Service. © 1999

Introduction

Work on a new fuel line and the Cleetwood Cove Trail prevented last year’s visitors from fishing or taking boat tours, so the summer of 1999 promises a return to Crater Lake. Not since 1952 had a whole season passed without public access to the water, so it seemed fitting to begin this edition of Nature Notes with articles about the lake and the spectacular geological story it represents.

As anyone who has experienced the beauty found in its forests, wet lands, and even barren areas will readily attest, there is more to Crater Lake National Park than its central feature. Since each part of the park contains something of interest, Nature Notes is devoted to providing visitors with information they might not otherwise obtain on their own. In this edition, for example, there are articles on how to identify the various sedges, a rare wildflower called Mount Mazama collomia, and why weather plays a some times defining role in the visitor experience.

Change occurring over the length of one, possibly two, lifetimes is the common thread among the last three contributions. One article touches on the importance of memory to continuity in the park, while another piece about the habits and management of bears is essentially a retrospective. The last article describes what can be found in the seemingly mundane area around Whitehorse Creek in order to emphasize that repeated visits often result in new understanding about a place.

Nature Notes from Crater Lake is made possible by the Crater Lake Natural History Association, now in its 58th year. It sponsors this publication as part of an ongoing commitment to support the educational and resource management programs of the National Park Service. Please join them in this effort by becoming a member of CLNHA and receive a 15 percent discount on items sold in the William G. Steel Center at Park Headquarters or at the summer visitor center located in Rim Village.

NPS photo by George Grant, 1936.

Born of chaos, fire and smoke,

Turbulent nature did’st invoke

Mazama’s fall—that thou should’st be

Silent, mysterious, sapphire sea.Belle Menefee Meyer, 1941

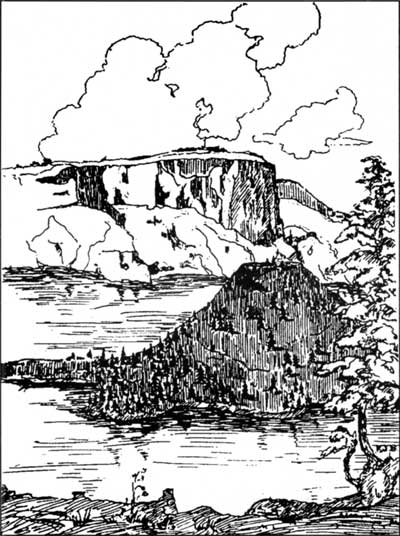

Wizard Island and Llao Rock by Karl J. Belser.

Answers from the Deep

Crater Lake is certainly a sight to behold. It is especially spectacular for those who see it for the first time. Pictures cannot really capture the lake’s magnitude and its image seems ageless. The base of the great volcano, which stood here once, properly frames the cobalt blue of the lake. These rugged cliffs are mostly bare, undoubtedly stripped of vegetation by continual rockfall. What of Wizard Island? It somehow seems fitting to have a winged dinosaur fly in circles around the cone. These creatures were long gone, however, when the fires of Mount Mazama first began to burn less than a half million years ago.

The apparent serenity of this lake is somewhat misleading. We must face the reality that this image is fleeting, or in the geologic time scale, ephemeral. Why should we expect Crater Lake to always be the same when it has changed so much in the past? A deep lake with a small volcanic island near one shore are its dominant features, though how each formed has been somewhat of a mystery until recently. By analyzing lake sediments obtained from the bottom, scientists can now tell us much more about what has happened here since Mount Mazama last erupted 7,700 years ago.

This crater (or caldera) holding Crater Lake today was created by a great eruption. That event ended with the collapse of the mountain summit, and was much more catastrophic than the Mount St. Helens incident in 1980. It may have been the biggest occurrence of its kind in North America during the last several million years. During the eruption, Mount Mazama released great quantities of ash and pumice. At least 12 cubic miles of mountain top disappeared as it slumped back into a drained magma chamber located beneath the volcano, now below the lake bottom.

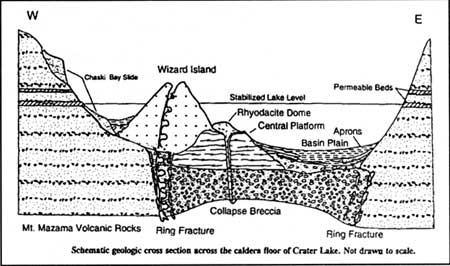

During the summers of 1988 and 1989, a piloted submersible was used for the first time to explore the bottom of Crater Lake. Videos identified active thermal springs on the caldera floor, indicating the presence of heat below. Hot water rises up, in various locations, through layers of lake sediment that have accumulated since Crater Lake formed. Five sediment core samples were taken from selected sites on the lake bottom during these dives. The sample taken east of Wizard Island, on a series of lava domes called the Central Platform, lacks the rock debris covering other sites and therefore better displays the materials that have settled here from above. These include volcanic ash, soot from forest fires, pollen grains, and diatoms layered in a fine mud about five feet in depth. By looking closely at this core sample, geologists can now work out what kind of events have transpired in and around the caldera over the last several thousand years.

Diagram courtesy of U.S. Geological Survey.

At the core’s base is mud, whose age indicates that it was deposited very soon after the caldera was formed. Dr. Charles Bacon, a volcanologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, speculates that only 300 years may have been needed to fill the lake basin to its present level. By the time water flowed over the top of the Central Platform, something that took a minimum of 150 years, the lake was already 1,000 feet deep over in the eastern basin, Obviously, winter snow and ground water easily found a repository in the large cavity left by the devastating eruption of Mount Mazama.

Crater Lake was approaching its present depth when Wizard Island appeared. We know this by examining its lava rocks 250 feet below the present water level. This was the water line for the lake when the event that produced Wizard Island occurred. The lava above this point looks different than the same lava below it. The lava, which was forced to cool in water, is left with a somewhat glassy appearance. The same rock, which cooled above the level attained by water at that time, has an oxidized surface and appears rusty red or brown. Since Crater Lake was lower when Wizard Island formed, it was not yet an island, At least several more decades were needed to allow the lake to enter Skell Channel and inundate the lava flows that connected Wizard Island to the caldera walls. Some of this lava made its way into the sediment over the Central Platform. Since the sediment appears near the core sample’s base, it provides more evidence that Wizard Island appeared not long after Mount Mazama collapsed.

The core sample extracted from the Central Platform shows that a second volcanic event occurred. Located approximately at the midpoint in the lake sediment is an ash deposit from activity related to creation of the Rhyodacite Dome, a feature situated immediately east of Wizard Island. Organic material within the ash layer indicates this eruption occurred 5,100 years ago. This is possibly the most recent volcanism related to Crater Lake. The absence of other activity since that time, however, does not indicate the volcano’s extinction.

Sediments on the lake bottom also contain pollen grains and diatoms. Scientists can broadly ascertain vegetation history patterns and related climate changes over the past few thousand years by studying them. Pollen, carried by the wind, entered the caldera soon after it formed, Even though the local pine and fir forests were decimated during the climactic eruption, other conifers located further away persisted. As water began to accumulate, pollen grains became a permanent part of the lake sediment. The appearance of pollen from Abies (true fir) in the core samples may be evidence for the recovery and reestablishment of the local forest, Fir pollen is relatively heavy and does not travel far from its source, It first appeared in lake sediments after a few hundred years, but just as this species became well-established, it and certain pine species began to decline. The pollen record shows that incense-cedar, western juniper, and Douglas-fir (all of which prefer a warmer and drier climate than the true fir) replaced them. These conditions prevailed for a thousand years and affected the entire Pacific Northwest. Pronounced change took place at lower elevations, where Lower Klamath Lake and Tule Lake all but disappeared. What effect the dry climate had on Crater Lake is not known. Currently, 67 inches of annual precipitation are needed to maintain the lake level. Evaporation and seepage would lower the lake level without a steady input from rain and snow. Perhaps Wizard Island was, once again, connected to the caldera walls during this period.

Pollen on lake in Steel Bay. NPS photo

Diatoms in the core samples provide researchers with information about lake water at various times. These microscopic silica skeletons are the remains of a type of algae and there are many different forms. As with other plants, the presence of one species or several related species can tell scientists something about the local environment, Eighteen different species of diatoms were examined from the core samples. Nine of them drift in the water column, whereas the other nine prefer the bottom of the lake.

The first species to establish itself was Stephanodiscus, a type of diatom that prefers fresh water, Others requiring a more mineral-rich and basic supply of water slowly replaced them and in abundance. This change may indicate that the lake water was slowly enriched with chemicals from hydrothermal vents, not unlike those seen with the submersible. Diatom concentration reached a maximum about 4,000 years ago following the dome building event that occurred east of Wizard Island, Since then, concentrations have slowly decreased for most species, though why is not well understood, Lake transparency has improved with this decrease since diatoms are effective scattering agents. In large concentrations they prevent light rays from travelling very far. With this in mind, Dr. Hans Nelson, a limnologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, is convinced that the lake’s exceptional clarity is a relatively recent phenomenon.

The peaceful setting of Crater Lake at the present time stands in sharp contrast to the violence which produced this picture. In the absence of continued volcanic activity, the water has slowly been purified by an abundance of rain and snow. We are often reminded by geologists that this volcano is only dormant. If the past is any indication of the future, the tranquility we enjoy today is only temporary. A new mountain may stand here someday and it is possible that our descendants may be limited to only imagining the lake we now see.

References

C.H. Nelson, et al., “The volcanic, sedimentologic, and paleolimnologic history of the Crater Lake caldera floor, Oregon: Evidence for small caldera evolution,” Geological Society of America Bulletin 106 (May 1994), pp. 684-704.

C.R. Bacon, “Geological Observations and Sampling,” pp. C1-C3, in Robert W. Collier, et al (eds.), Studies of Hydrothermal Processes in Crater Lake,OR, OSU College of Oceanography Report #90-7, Corvallis, May 31,1991.

Tom McDonough teaches science at Chemeketa Community College in Salem, Oregon and began working seasonally at Crater Lake National Park thirty years ago.

The Filling of Crater Lake

It was 30 years ago last summer since I last worked at Crater Lake. From 1966 to 1968 I was a seasonal park naturalist and during that time I conducted research on the vertical migrations of zooplankton in the lake. This research led to a masters degree in limnology and ecology from Oregon State University in 1969. Last August I volunteered for one week as a way to reacquaint myself with the park. I soon realized that I had forgotten many facts and quite a few had been revised since my last time in uniform. This dictated a visit to the park library.

One of the intriguing questions I came across in my brief survey of park-specific literature was: how quickly did the lake form, or how many years did it take to reach the present water level? I looked in the library, but found little or no information about what might seem to be a worthy focus of scientific investigation. The best thing I found was a paper published in 1994, where the authors claim that Crater Lake reached its current level in only 300 years (Nelson, et al. 1994). Being curious, and traveling with my laptop computer, I began to develop a simple mathematical model of the lake aimed at obtaining the answer (if only in an approximate way) to this question.

Methods

My mathematical model was initially constructed on the basic assumption that the hydrological processes of the past are not dramatically dissimilar to those of the present. For starters, I assumed:

(a) annual precipitation of 30.4 billion gallons (Phillips and VanDenburgh 1968);

(b) annual average evaporation of 15.2 billion gallons, based on an estimated evaporation rate of 120 cm per year (Redmond 1990);

(c) subsurface seepage that depends on the amount of water in the lake at any time.

For my initial calculations, I set seepage at 0.33 percent of the lake’s volume per year (as derived from a net annual input of 15.2 billion gallons divided by the lake volume of 4.6 trillion gallons). Since evaporation will change somewhat with lake depth, I added an adjustment factor to account for the increase in surface area occurring as the lake filled to its present depth. I included an additional adjustment to the seepage rate to simulate more seepage with increasing depth as the lake filled. This adjustment accounts for both increased pressure from a rising lake level and increased bottom surface area. In the beginning, when there were only 230 billion gallons of water (assumed to have accumulated from ground water and hydrothermal sources), seepage is therefore estimated at 0.03 percent of lake volume. Conversely, when the lake became half full, seepage was about 0.2 percent of lake volume.

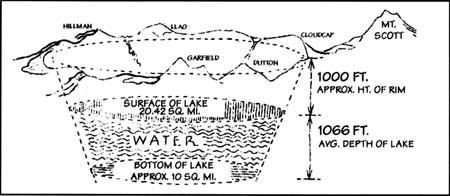

Illustration used by J.S. Brode, estimating water volume in Crater Lake, September 1934.

The model is based on values for present conditions, but this cannot be assumed over the entire period of lake formation. Analysis of the lake sediment and samples of pollen indicate that, at least initially, the climate was not unlike today (Nelson et al., 1994). It is thought that Wizard Island formed not too long after the collapse of Mount Mazama and that the lake was within 250 feet of its current level at that time, Consequently, I assume that conditions of precipitation and temperature similar to the present day, existed for roughly 400 to 500 years after Mazama’s collapse. Soon afterwards, however, a warmer and drier period commenced and lasted as long as 1,000 years. This drier period affected the entire region of the Pacific Northwest. Exactly how dry was it? No one really knows for sure, but to simulate this effect I reduced precipitation during this time period to between 30 and 50 percent of present day averages while also increasing evaporation by 10 to 20 percent.

To simulate the filling of Crater Lake, I used the software package STELLA II which has been specifically designed for the development of models for time dependent phenomena. This software is ideal for examining the effect of different assumptions about climate on the formation of Crater Lake.

Results

Crater Lake was formed in the collapsed caldera of Mount Mazama. Its formation began soon after the collapse, almost as quickly as the caldera floor cooled to the point where water could accumulate on the bottom, The evidence to date suggests that the young lake probably resulted from ground water draining back into the caldera from the surrounding slopes and hydrothermal springs. Since annual precipitation did not vary substantially from that of the present climatic regime, the lake rapidly (in geological terms) increased in depth–gaining much more than the present net input of 15.2 billion gallons of water per year. The actual gain would depend upon the amount of evaporation, relative to the increase in surface of the lake, with early seepage having a negligible contribution to the annual loss.

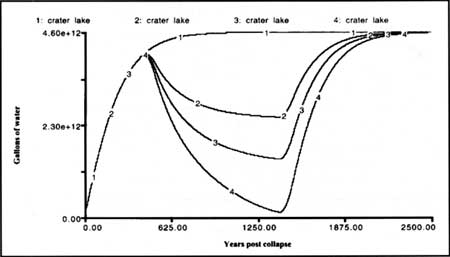

Fig. 1: Four model simulations of the filling of Crater Lake with time. The first simulation (1:Crater Lake) assumes that present day annual precipitation has been constant over time. The second through fourth simulations (2-4:Crater Lake) assume for a 1,000 year altithermal period that prevailed between 500 and 1,500 years post collapse a reduced precipitation rate that is 0.7, 0.6 and 0.5 times that of the prsent, and an evaporation rate that is increased respectively 10%, 15%, and 20% above the present.

Based on these assumptions, Crater Lake probably reached about half of its present size within 150 years (Fig. 1), rising at a rate of some three to four feet per year. After roughly 300 years, the lake would have reached the level that was present at the time of Wizard Island’s formation. This also means that at 400 years since the collapse of Mount Mazama, Crater Lake reached about 90 percent of its present volume.

Approximately 500 years after the collapse, a 1,000 year period of drier climate ensued. This caused the lake surface to fall steadily and by the time this “altithermal” or “xeric” period gave way to cooler and more humid conditions (not unlike the present time), the lake could have lost between 40 and 80 percent of the peak volume reached at the onset of the dry period. As precipitation increased, the lake once again started to rise and reached 95 percent of present day volume about 2,000 years after Mount Mazama collapsed. The final stage of filling Crater Lake took another 500 years and required conditions that produced a relative equilibrium among precipitation, seepage, and evaporation. Because of the changes in climate, complete equilibrium among precipitation, evaporation, and seepage did not occur for another 1,500 to 2,000 years thereafter. In other words, it took about 2,200 to perhaps more than 3,000 years for the lake to reach the present state of complete equilibrium with an average depth of 1,066 feet (325 m) and a maximum depth of 1932 feet (589 in). If it were not for the 1,000 year dry period, Crater Lake would have reached its present level between 1,100 and 1,500 years after Mount Mazama’s collapse 7,700 years ago. Due to the 1,000 year dry period, evaporation and seepage exceeded precipitation and the lake fell to more than half its present level (Fig. 1). During this dry millennium it is likely that the lake water would also have been richer in minerals, more biologically productive, and thus less transparent than it is at present.

Crater Lake in the Future

Is the lake always going to stay like it is today? Given enough time, most certainly not. Perhaps the most imminent change, however, will be that of climate and its effect on precipitation. Any change in annual precipitation will have a direct effect on the level of Crater Lake. If precipitation begins to decline as climate changes to a drier condition, evaporation and seepage will again exceed precipitation so the lake level will drop. If precipitation increases, the lake level should rise and perhaps find a new equilibrium. There is no evidence to date that Crater Lake ever reached levels substantially above present. Nevertheless, such changes may occur over the next century or so. Over the next few thousand years, however, pronounced climate changes are certainly anticipated and with these changes will come fluctuations in lake levels, If we project ahead even further in time to, say, one million years or more, then it is likely that renewed volcanic activity or some other process of mountain building will occur, These major processes will dramatically change the appearance and structure of Crater Lake as we now know it. Few lakes on Earth have had a life-span that transcends a million years.

References

C.H. Nelson, et al., “The volcanic, sedimentologic, and paleolimnologic history of the Crater Lake caldera floor, Oregon: Evidence for small caldera evolution,” Geological Society of America Bulletin 106 (May 1994), pp. 684-704.

K.N. Phillips and A.S. VanDenburgh, Hydrology of Crater, East, and Davis Lakes, Oregon. USGS Water Supply Paper 1859-E. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1968.

K.T. Redmond, “Crater Lake climate and lake level variability,” pp. 127-141 in E.T. Drake, et al (eds.), Crater Lake: An Ecosystem Study. San Francisco: Pacific Division, American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1990.

F. Owen Hoffman spent the summers of 1966 through 1968 as a seasonal naturalist at Crater Lake. He volunteered at the park for one week in 1998.

Sedges Have Edges

“Sedges have edges; rushes are round; grasses are hollow right up from the ground”1

|

Carex nigricans black alpine sedge single spike |

|

Carex luzulina woodrus sedge cylindricdal spikes |

|

Carex athrostachya slenderbeak sedge dense head of spikes |

The jewel like wet meadows of Crater Lake National Park owe their rich green color largely to a group of grasslike plants, the sedges (the genus Carex in the plant family Cyperaceae). Sedges can be found in many other habitats such as forests, streams, and dry pumice fields. These plants have edges because their stems are triangular rather than being round like grass or rushes. Sometimes the sedge edges are very sharp due to a row of tiny teeth along the stem angles (sedge leaves also have these sawtoothed margins). In fact, the name of the genus Carex derives from the Greek word meaning “cutter.” Sedge leaves grow in three rows, one along each side of the stem, so that looking down on a sedge plant from above you see leaves extending outward in three distinct directions. Grass and rush leaves, by contrast, grow in two rows. Furthermore, sedge stems are solid, not hollow, like grass stems.

The flowers of sedges are small and appear greatly reduced from the form of familiar wildflowers such as lilies and violets. Sedge flowers have no petals, with each flower possessing either male or female parts but not both. Male flowers consist of three stamens (the pollen-producing structures), whereas female flowers contain the ovary enclosed within a sac-like structure called the perigynium (peri = around, gyn = female, ium = little). Much of sedge identification depends on the size, shape, color, and texture of the perigynia, and looking at these features requires a magnifying lens.

Sedge flowers are borne in dense spikes. Depending on what kind of sedge it is, each spike may contain only male flowers, only female flowers, or both. A few sedge species can have separate male and female plants. Sedge spikes range from short and egg-shaped to long and cylindrical. The arrangement of spikes on the stem usually fits one of the following four general forms: a single spike (only one flowering spike per stem), a dense head (many short spikes per stem, closely crowded into a dense cluster), the “extended head” (a long loose cluster of short spikes), and the “bottlebrush” type. The “bottlebrush” sedges have a few long cylindrical spikes on each flowering stem, and the spikes often look like tiny bottle brushes when the flowers are in full bloom). Three of these types are shown at the beginning of this article.

There are about 40 different species of sedges in Crater Lake National Park, more than for any other genus of vascular plants. Many of these sedges respond vigorously to lower-intensity fire, sprouting and forming dense swards in burnt areas, For example, following surface fire in ponderosa pine forests in the northeast corner of the park, long-stolon sedge (Carex pensylvanica, also known as C. inops) increases in cover. When people talk about the lush “grass” growth in some of the areas burned by the 1988 fires at Yellowstone National Park, they are usually talking about sedges. Such vigorous regrowth is very important in stabilizing denuded soil and in providing food for wildlife where food supply has been reduced. A variety of wildlife relish sedges and rely on them for nutrition; these include waterfowl, small mammals, as well as the charismatic deer and elk.

Sedges are also important to humans. Their strong, tough fibers, sedges were used by American Indians to make cordage, basketry, and mats. Sedges that have creeping underground stems (rhizomes) were an especially important source of fiber for technology, but whole above ground stems and leaves were also twisted into rope. One late 19th century account refers to the use of commercially-made rope for constructing a building in northern Idaho. The rope frayed and broke, so they made a new rope. This one used locally-growing sedges and did not fail.

Many sedge species look alike and learning them involves looking closely at their characteristics. Sedge identification keys rely on having mature perigynia and knowing the growth habit and habitat of the plants. Identifying sedges is a specialized skill, but once the terminology becomes familiar, learning the plants is very enjoyable and intellectually challenging.

| “You pull off the parts, and soon feel your age Chasing them over the microscope stage! You peer through the lenses at all of the bractsAnd hope your decisions agree with the facts; While your oculist chortles with avid delight |

Notes

1Anonymous

2Excerpts from a poem in H.D. Harrington, How to Identity Grasses and Grasslike Plants (Swallow Press, 1977)

Joy Mastrogiuseppe has specialized in the study of sedges at Washington State University ever since she worked as a seasonal employee at Crater Lake in the 1970s.

Drawing appeared in the September 1937 edition of Nature Notes from Crater Lake.

Other pages in this section