Memory and Symbiosis on the Rim

Visitors to the rim of Crater Lake can experience something special that was noted by the Lewis and Clark expedition nearly 200 years ago. When the Voyage of Discovery came to a place called Lemhi Pass in the Bitterroot Mountains (along the border of present-day Montana and Idaho), William Clark recorded the following in his journal on August 22, 1805:

I saw today a Bird of the woodpecker kind which fed on Pine Burs—its bill and tale white, the wings black, every other part of a light brown, and about the size of a robin.1

This entry is the earliest known written description of a Clark’s nutcracker and the whitebark pine. The nutcrackers and whitebarks still live at Lemhi Pass. A few of the pine trees may even be the same individuals that bore witness to Lewis and Clark’s Voyage of Discovery; others may have been planted by the very birds the explorers were watching.

Clark’s nutcrackers are certainly popular with visitors to the rim of Crater Lake. This bold crow marked with gray, black, and white contributes as much entertainment to their experiences as the golden-mantled ground squirrels. The nutcrackers especially favor peanuts and collect as many as visitors will provide despite the “no feeding” regulation. Any nuts not promptly consumed by the birds are placed into storage caches for winter food, This caching behavior is the same as nutcrackers employ with whitebark pine seeds when the trees produce sufficient quantities of cones. Mature whitebark pine cones do not open, and the foraging nutcracker is the pine’s primary seed dispersal agent.

Clearly, the nutcracker is a keystone species since it plays a role in perpetuating several different kinds of pine. A keystone species is one so closely connected with other organisms that if the keystone species becomes rare or extinct there will follow other losses and negative effects in food webs. Whitebark pine is an important food source for squirrels and bears as well as for nutcrackers. The endangered grizzly bear in the northern Rocky Mountains utilizes whitebark cones as a critical food source prior to winter hibernation. Whitebark pine also is a pioneer species in subalpine areas, often being the first tree to establish itself in what will become tree islands or atolls.

Whitebark pine populations are in trouble. Glacier National Park, for example, has already lost over 90 percent of its whitebark pines. These woodlands, as distributed in the northern Rocky Mountains and at high points throughout the Cascade Range, are threatened for several reasons. First is an exotic fungus called white pine blister rust(Cronartium ribicola), that produces spores on the leaves of gooseberry and currant shrubs (the genus Ribes). These spores germinate in the bark of pines and eventually girdle the tree. Since Crater Lake’s whitebarks are often skirt by the local endemic Crater Lake currant (Ribes erythrocarpum), a potential source of infection is close at hand, During periods of low clouds with high humidity, weather conditions favor fungal growth including the production and dispersal of spores. Secondly, the suppression of low-intensity fires has, over the long term, increased whitebark pine mortality from catastrophic bums racing upslope into the subalpine zone, Such an event occurred in August of 1978 on top of Crater Peak. Thirdly, mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae) infestations initiated in lower-zone lodgepole pine forests also threaten upslope whitebark pine woodlands. Lastly, the trend toward global warming will force whitebark pine woodlands upslope, where less habitat is available. This migration can only occur if cone production allows Clark’s nutcrackers to cache seeds in higher habitats as timberline advances upwards.

Whitebark pine. Drawing by Karl J. Belser, 1935. |

I can remember helping to trap and band Clark’s nutcrackers at the rim more than 30 years ago. This project continued work begun a decade earlier, when among the results from banding was the recovery in 1957 of a nutcracker banded at the rim. Just six weeks later it had been killed by an owl on the slopes of Mount Adams in Washington.2

Another fond memory of Crater Lake involved spending an autumn night in the Watchman Lookout and waking at dawn to the sight and sound of a nutcracker flock prying open an abundant crop of whitebark pine cones. Thirty years ago, healthy whitebark pines graced Wizard Island’s summit crater, but today they are reduced to bleached, weathered skeletons. When I visit Wizard Island I remember those awesome pines, but visitors can now only experience them as nonliving relics.

National parks provide an opportunity to learn about nature and the idea of coexistence with other living organisms. The loss of any species brings with it the likelihood that future visitors will not understand what has vanished, Loss of keystone species is doubly distressing, since it can also damage any hope that the native biota can ultimately be perpetuated. As links in the food chain and in memory, the Clark’s nutcracker and whitebark pine play a vital role at Crater Lake National Park. Without them, there is serious danger that misconceptions about nature and even ourselves may arise.

“A land without memories is a land without history.”

(Author unknown)

Notes

1Quoted in R.M. Lanner, Made for Each Other: A Symbiosis of Birds and Pines. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 22.

2Donald S. Farner, The Birds of Crater Lake National Park (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1952), p. 88.

Ron Mastrogiuseppe started his career as a forest ecologist at Crater Lake and has become a leading contributor to Nature Notes since retiring from the National Park Service in 1993.

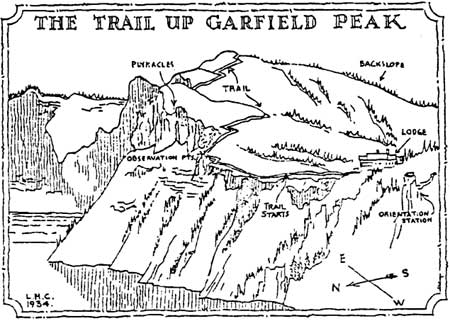

Diagram of Garfield Peak Trail by L. Howard Crawford, August 1934.