Where Art Imitates Nature

What we see as architectural heritage (that is, worth keeping) is often formal, ornate, and part of commemorating a significant event or person. There are buildings, however, that are preserved for other reasons. Some simply continue to serve an important function for their users, whereas just a few bear testimony to how designers allow occupants to feel integrated with their surroundings. One can argue that nature is something that people construct for themselves, but seeing it with a painter’s eye has a long European pedigree.

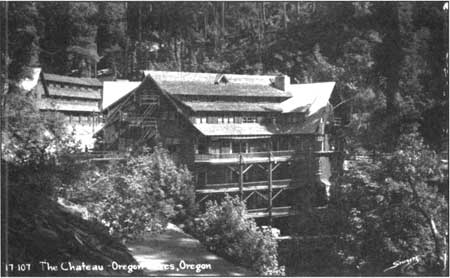

Situated only 25 yards or so from the cave entrance, the six story Oregon Caves Chateau spans a small gorge so that much of its mass seems hidden below the roadway. The size of this hotel is further downplayed by extensive landscaping with native vegetation and rock from the surrounding area. A steep gable roof with intersecting parts and dormers makes each side of the building appear different from the others. This reflects the variety found in nature, as do windows and doors configured to fit the scene. An exterior sheathing of Port Orford-cedar bark is a distinctive feature and brings about unity with other structures at Oregon Caves National Monument.

Oregon Caves Chateau in 1940. Oregon State Highway Commission photo.

Visitors entering the Chateau’s main doors next to the road will see a lobby evocative of the time in which this structure was built. One concessioner began operations at the monument as soon as the Oregon Caves Highway opened in 1922, but could provide only some tents for overnight accommodation. The following year a group of Grants Pass businessmen formed the Oregon Caves Company and announced plans for a resort at the monument. It took, however, the impetus provided by government funding for improving the highway, installing electric lights in the cave, and then blasting an exit tunnel, for the company to consider building a hotel.

The monument’s rugged and oversteepened topography dictated that a large structure could be sited in only one place if it were to be located close to the cave entrance. That meant the hotel had to be built within a “gulch” next to where Cave Creek spills out from the Marble Halls of Oregon. This architectural challenge fell to Gust Lium, brother in law of a businessmen who helped to form the company. A man who spoke with a strong Norwegian accent, but was born in North Dakota, Lium designed and built many residences and commercial structures around Grants Pass beginning in the early 1920s. He enjoyed a solid reputation, and worked by the “measure twice, cut once” philosophy.

Lium’s crew never numbered more than 20 at any one time once he started construction in 1931. The bottom of the Great Depression brought some delays because money was tight, but the project finished on time in 1934. That spring a rail carload of furniture arrived from California, some of which can be seen in the hotel lobby. Perhaps more evident, at least to those who enter for the first time, is a massive freestanding double fireplace made of native marble. Adding to the ambiance are the massive logs that serve as beams and posts. These appear to be hand joined by wooden pegs, but this detail is only decorative. Wrought iron sconces are attached to the posts and are augmented with lights shaded by laced parchment that hang from the ceiling. Handcolored historic photographs of various tourist destinations in the region add interest to several walls in this room, enticing many visitors to explore the Chateau further.

The main staircase is one of the more ingenious pieces of construction in the entire building. It is open and contains rectangular oak planks for treads notched into peeled log stringers. The balustrades are madrone and support handrails made of lodgepole pine. This staircase can lead one up to guestrooms on the floors above, each level faintly imitating the maze of a cavern where oddly shaped chambers have windows with which to survey the sylvan scene outside. Those not staying overnight might wish to use the staircase for descending to the dining room and coffeeshop. The dining room is known for diverting part of Cave Creek through it by means of a conduit, in addition to a superb view down the drainage. A flood in December 1964 necessitated extensive repairs to the coffeeshop, but it retains some redwood wainscoting, as well as birch and maple counters that complement the soda fountain.

Cave entrance from the future site of Oregon Caves Chateau, about 1912. U.S. Forest Service photo.

During business hours patrons can exit from either the dining room or the coffeeshop through the courtyard. A pool built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1935 constitutes its central feature and is fed by an eight foot waterfall. The pool, waterfall, drywall masonry, and plantings of fern, shrubs, and specimen trees demonstrate how landscape architects hired by the National Park Service worked with the CCC to create what really is a garden. A conspicuous lack of formality in the courtyard and in other landscaping around the Chalet makes the composition “naturalistic.” In this type of design, emphasis is placed upon using vegetation and materials native to the area and then arranging the most pleasing forms to meld development with the setting.

Naturalistic design has its origin in the history of private estates, at a time when the owners wished to extend the garden outward and surround the house to create various scenes or one “landscape.” Imitating the variety found in nature, yet providing order and unity for what could not occur of its own accord, drove development in public parks through much of the 19th century. Many of these parks were established in cities and adapted from private estates, so that the citizenry could enjoy the perceived benefits of the country. The “rustic architecture” of buildings that fit their natural surroundings became models for developing facilities in parks established to conserve features that displayed the nation’s heritage. The Oregon Caves Chateau is a National Historic Landmark because it demonstrates how rustic architecture and naturalistic design adapted to a new setting and embellished one of America’s oldest national monuments.

Steve Mark is a National Park Service historian who has served as editor of Nature Notes since its revival in 1992.