Small Shards of Stone

Nascent geologists quickly learn that there are three basic rock types: sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous. Crater Lake National Park lacks both the sedimentary (rock fragments or natural cements under conditions found near the earth’s surface) and metamorphic (rocks transformed in appearance or mineral composition through intense heat and pressure, but without melting), yet is abundantly blessed with igneous rocks, The latter are those rocks formed from molten rock or magma, and can be further divided into volcanic or plutonic rocks. Volcanic igneous rocks form when magma erupts and reaches the earth’s surface, then hardens. Plutonic igneous rocks form when magma cools slowly underground, as in the case of granite. Plutons can sometimes be exposed at the surface through the process of erosion, uplift, or even by catastrophic geological events.

Volcanic rocks are divided into categories ranging from rhyolite to basalt, depending upon how much silica they contain. In ascending order, the spectrum at Crater Lake includes basalt, basaltic andesite, andesite, dacite, rhyodacite, and rhyolite. Lots of other terms refer to the texture and form these rocks assume after a volcanic eruption.

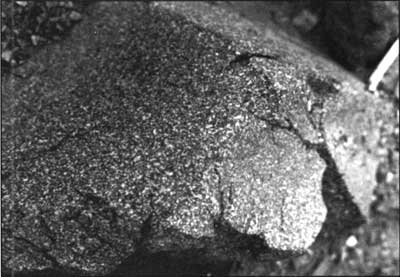

Although a wide range of volcanic rocks can be found in the park, the only fairly common plutonic rock found here is granodiorite. It occurs in all deposits associated with Mount Mazama’s climactic eruption, but is most abundant in late-erupted volcanic material. This material is very often ignimbrite, a “tuff” of welded crystal and rock fragments within a matrix of glass shards. These formed as a deposit from a rapidly moving, turbulent, and ignited cloud of gas flowing from a violent volcanic eruption. Granodiorite fragments found around the caldera came from the walls of the magma chamber that produced the climactic eruption. Being somewhat similar in appearance to granite, they are easy to distinguish at close range since the generally grey-black rock contains whitish crystalline specks.

Plutonic rock close up. Speckled appearance indicates crystalization. Photo by Steve Mark.

A nice example of a granodiorite fragment can be seen at Rim Village. It is roughly the size of a dishwasher or a little larger, and sits on a bank near the lodge parking lot not far from the road junction to the concessioner’s dormitory. On one side of this plutonic rock is a carving that detracts from its appearance, but the fragment still has much to convey about Mount Mazama’s climactic eruption. The granodiorite crystallized 110,000 years ago in the same location where a large magma body later accumulated, one that eventually powered a violent series of climactic eruptions. In all probability the pluton made an impermeable barrier for the newer magma chamber, one whose rigid container also facilitated a progressively explosive accumulation of magmatic vapors. Much like an over primed bottle of beer, where the ever-expanding pressure of its contents ultimately leads to an explosion, Mount Mazama gave way some 7,700 years ago.

Reference

C.R. Bacon, et al., Late Pleistocene granodiorite beneath Crater Lake caldera, Oregon, dated by ion microprobe, Geology 28:5 (May 2000), pp. 467-470.

Steve Mark is a National Park Service historian who has served as editor of Nature Notes since its revival in 1992.