Presenting Crater Peak and the Pacific Crest

It is hardly worth repeating that Crater Lake plays a central role in what most people experience in this particular national park. Roads provided the main access for seeing the lake even during the first decade after the park’s establishment in 1902. By 1919 a “rim road” of some 35 miles allowed visitors to drive completely around the edge of a caldera holding Crater Lake. This route was superceded by construction of a more modern “Rim Drive,” an almost 33 mile summer thoroughfare which persists to the present. While the latter road has become one of the top scenic drives in the United States, it also made seeing Crater Lake so easy that for the last 60 years or so the average visitor spends a little less than four hours in the park.

Trails have always been of secondary concern to managers over the past century, especially when compared to the attention given park roads. One observer commented in 1932:

I was told at the Park that little money will be given for trails because few people use the trails. It is more important to build trails for the few who have interest enough to use them than to build roads for the many. It is of little value to run thousands of people up to a scenic point and then hurry them past it to another point. Nature speaks only to one who has ears and time to listen.1

The old giving way to modern means of experiencing national parks, 1942. |

Indeed, most of the park’s trail mileage consists of old fire access roads (sometimes called “motorways” or “truck trails”) which formerly allowed firefighters the ability to respond quickly once lookouts spotted lightning caused blazes from The Watchman or Mount Scott. These roads were maintained as such until 1971, when managers started to treat much of the backcountry as wilderness that exhibited characteristics to some day qualify for legal designation under the Wilderness Act.

Advent of the Fee Demonstration Program in 1997 allowed for a hard look at the fire roads currently in use as trails. Entrance fees to the park for most vehicles were raised from $5 to $10, with 80 percent of that increase to be retained by the National Park Service for various projects. One of these focused on providing a better visitor experience on the old fire roads. Highest priority treatments were to be aimed at addressing safety concerns or improving segments irreparably damaged by past use as roads, such as drainage problems defying any solution attempted in annual trail maintenance efforts.

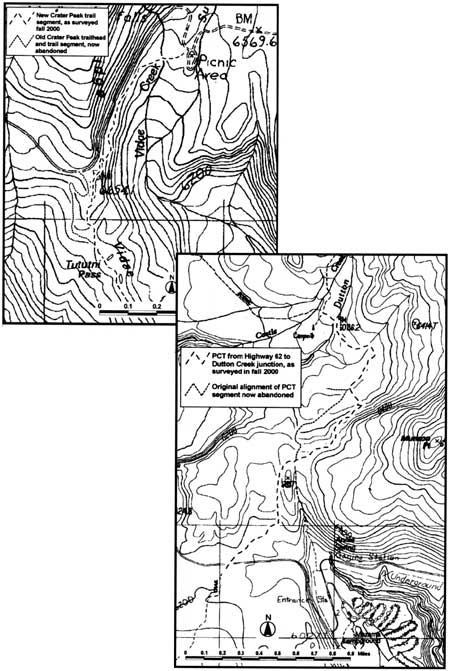

After conducting a review of all fire roads used as trails in the park, two projects involving short reroutes headed the list of possible projects to be funded by a Fee Demonstration account. One was connected with traffic safety at the trailhead (a blind curve on Rim Drive), damaged tread stemming from closure as a fire road in 1971, as well as a picnic area badly in need of revegetation and rehabilitation of its vehicular circulation system. A big question behind making a new trailhead for Crater Peak at the Vidae Falls Picnic Area lay in the feasibility of placing trail on the old rim road route, especially in the section involving a climb up a talus slope full of boulders. The other project seemed less complex, as the bulldozer creating the fire road in 1929 also produced a chronic drainage problem. This section is located west of Annie Spring, where the Pacific Crest Trail drops into the Castle Creek drainage, something best avoided by a proposed reroute heading north along the divide posed by Munson Ridge, then descending on gentle switchbacks toward Castle Creek’s tributary of Dutton Creek.

Above: Annie Spring/PCT reroute. Right: One map for Crater Peak Trail.

Planning for both projects started with extensive reconnaissance over ground to weigh the merits of alternative routes. A landscape architect then produced a site plan for the Vidae Falls Picnic Area, to be followed by specialists who conducted surveys for rare plants and archeological resources in the corridors chosen as preferred options for reroutes. Recommendations for revegetation covered several miles on both the Crater Peak and Pacific Crest trails. This report aimed at giving specific guidance to those who were going to undertake the laborious task of removing scars left by the old fire roads. Crews needed to know, for example, where to recontour road berms in order to narrow the trail to a footpath some 18 inches wide and what vegetation to salvage as they did so.

Crater Peak in the distance. NPS photo. |

With all of the planning and surveys completed in 1999, implementation came about the following summer. Work began in August, when the Friends of Crater Lake assisted the park’s trail crew in constructing the first quarter mile or so of tread from Vidae Falls Picnic Area. Enrollees from the Pacific Northwest Youth Corps then assumed the difficult task building trail through a boulder-strewn section in order to connect the path from the picnic area to the existing route leading to Crater Peak. The PNYC also labored to make the short reroute of the Pacific Crest Trail near Annie Spring a reality by Labor Day.

Anyone who reaches the junction of where trails from Annie Spring and Highway 62 join on the Cascade Divide will no longer follow an old fire road to make an immediate descent. They instead follow a winding path for an enticing view of a dry meadow located up slope of the trail, followed by a ridgeline panorama featuring The Watchman and Hillman Peak in the distance. Some easy switchbacks are encountered shortly thereafter, ones traversed with little effort before rejoining the old PCT enroute to crossing Dutton Creek.

An even more stunning transformation awaits those who head for Crater Peak. The new trailhead at Vidae Falls Picnic Area allows hikers an opportunity for contemplation at the shaded crossing of Vidae Creek, followed by a climb where the spectacular canyon of Sun Creek can be seen from the trail for the first time. This route then winds its way up the talus slope and finds a natural rock wall located on the saddle that allows the old trail to bring hikers toward the base of Crater Peak. The new trail eliminates a series of “tank traps” near East Rim Drive and a wandering traverse that produces neither a view of the canyon nor hardly a glimpse of the cinder cone.

Both reroutes are attempts to provide hikers with a better trail experience than afforded previously by the fire roads. Success in this respect is fairly subjective, but weighing trail design against the following experiential characteristics that make for a good walk might help in judging projects such as these. Mystery is where landscapes give the impression that one could acquire new information by traveling deeper into the scene. Good trail layout accentuates mystery and features a winding path, where constantly shifting views of vegetation and the landscape sustain interest. Legibilityallows for extensive exploration in an environment that looks easy to discern if a person goes further into it; trails can therefore utilize landmarks and periodic openness to reduce anxiety about getting lost. A prospect often highlights the hike, by providing a vista that extends for miles, even if in just one direction. Refuge describes places on or near the trail that provide seeing without being seen, whereby information is gained without giving any away.2

Whatever the verdict, good design should mean that no one might notice what took place to improve the trails. That is, of course, unless you take the time to look closely at how nature is presented.

The author wishes to thank Cheri Killam-Bomhard and Amy Mark for their review and comment on the draft of this paper.

Notes:

1Worth Ryder, Report on Crater Lake [to John C. Merriam], August 1932, p. 4.

2Tony Hiss, “Reflections (Experiencing Places—Part 1),” The New Yorker (June 22, 1987), pp. 63-64.

Steve Mark is a National Park Service historian who serves Crater Lake National Park and Oregon Caves National Monument.