Others Have Passed This Way

Annie Creek, which forms a dramatic canyon along much of highway 62 coming to Crater Lake from the South Entrance, is called Tiwi in the Klamath language. This name arose in past centuries as people walked from the Wood River country in late summer toward their seasonal encampments at Huckleberry Mountain. In a time before wagon roads and highways, many preferred to reach patches located in the high Cascades south of Crater Lake by staying on the west edge of the canyon as they slowly climbed toward a small pass found just above Annie Spring. From there the general line of travel went west along Castle Creek, until those in search of berries veered south to follow the trail up the mountain.

Remnant wagon road of 1865 above Annie Spring.

Army road builders used portions of the Indian trail network in the Annie and Castle creek corridors to link Fort Klamath with Jacksonville in 1865. Their commanding officer. F.B. Sprague, subsequently wrote a series of newspaper articles for the Jacksonville Sentinel. One of the pieces gave particulars about the new road and included suggestions for where to camp along it. Knowing where stock could be watered and fed was crucial to any trek across the mountains. Having more than one or two options along the road could also reduce friction between parties who might otherwise need to share relatively limited resources. Distances traveled by wagons over several days or a week also necessitated that a number of potential overnight stops be available. As transportation became more efficient, many of these stopovers showed signs of decreasing use. Present day visitors are allowed to camp at only one of those overnight stops associated with the wagon road while in Crater Lake National Park. This site is along Dutton Creek, not far from the Pacific Crest Trail.

Other sites along the old wagon road, some situated just yards from Highway 62, were investigated by a team of archeologists and historians who conducted a reconnaissance survey on an intermittent basis each summer from 1998 to 2000. Participants found some 14 miles (of a possible 22 within park boundaries) of the old wagon road to be intact, even though highway realignments and widening chopped the road into segments above Annie Creek Canyon. A number of the old stopping places, however, become evident to anyone approaching at walking pace. These can also serve as launching points for hikers who have the time to see a little more of the park.

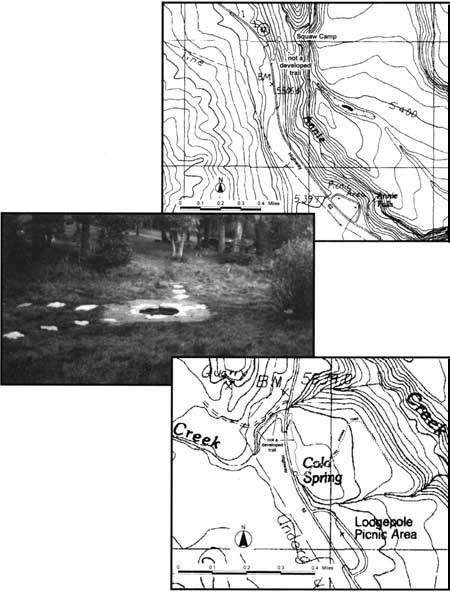

Above: Map of Squaw Camp vicinity. Above Left: Cold Spring in 1937. Below: The Cold Spring area.

Waterfalls attract people for numerous reasons. Annie Creek Falls, for example, can be seen from a distance at a picnic area located about midway between the South Entrance and Annie Spring on Highway 62. About a mile north of the picnic area is a fairly long paved pull out placed along the eastern margin of the highway. It is rather nondescript, being surrounded by thick “dog hair” stands of lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), although northbound travelers can see Arant Point ahead for the first time since entering the park. This dull, dry forest changes abruptly upon making a short descent below the highway toward Annie Creek. Wet areas fed by seeps and small springs in the canyon support far greater plant diversity than what motorists see at the pull out. Those hikers with a keen sense of smell may detect the odor of wild onion (Allium validum) growing in several places not far from the bottom.

Blazed trees, such as the one at right, are evident along portions of the wagon road. Photo by the author. |

A map printed in 1908 enticed the survey team to investigate this locality since it referenced “Squaw Camp” in the canyon. Sure enough, what might have represented a respite from hard travel to tribal members passing through the park a century ago is evident on both sides of the stream. These secluded terraces make what are perhaps the best campsites in the entire canyon. Just a short distance upstream is an impressive waterfall with a shallow pool below it. An even more imposing cataract can be seen if one follows the east fork of Annie Creek from its confluence with the main branch. This cascade and the other waterfall can be seen simultaneously if the viewer finds the right position.

Those visitors wanting a hike with less climbing can drive about a mile north from the paved pullout to the next picnic area. Park at the upper end and walk along the eastern side of the highway for a short distance, going along the small stream drainage. Its source is not immediately discernible amid another lodgepole thicket, but Cold Spring quickly becomes evident upon entering the small wetland where common (yellow) monkeyflowers (Mimulus gattatus) bloom in July and August. Surrounding the spring are older trees, many of them blazed by hatchet or axe at a time when horses and wagons were brought here. Those who wander a short distance may begin to see the outlines of a larger campground, one built by the National Park Service in 1937 and used into the 1960s. Sharp-eyed hikers will eventually spot a masonry fireplace, the last of its kind in the park, left mostly intact by crews who “restored” the area following closure of Cold Spring Campground about 30 years ago.

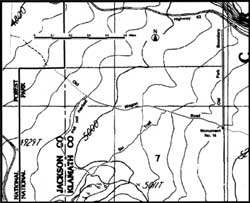

Map of the Thousand Springs vicinity. |

Two short treks are possible from the Cold Spring locality. An old service road leaves the campground heading east, then south, but remains high above the canyon. The other option requires crossing Highway 62 in order to follow the course of Polebridge Creek upstream. A hundred yards or so from the highway are bridge remnants where wagons once crossed. Follow the path out of the drainage, one that takes you south and west along a bench allowing for fine views of the creek and wetland. A couple of blazed trees indicate camp spots of long ago, just shy of the power line access road. There is a small huckleberry patch in the vicinity that may provide another reason to linger.

A half day adventure is possible for those who are inclined to explore the Thousand Springs vicinity. To reach it from the wagon road, start at the old West Entrance—this is located about one mile east of the present park boundary on Highway 62, or roughly seven miles from Annie Spring. There is a small paved parking area on the south side of the highway, near where the sign is suspended on a metal pole that dictates a 45 miles per hour speed limit. At the time of writing a .75 mile hike is necessary to reach the wagon road, so use a compass to avoid wandering too far off line.

The wagon road route will be obvious and permits comparatively easy walking in a westerly direction, to the place where a placard with an arrow is nailed to a tree containing a blazed arrow. These arrows indicate where a Nordic ski loop diverges from the wagon road, one that follows an older route leading to water. A meadow containing a number of blazed trees will be reached after walking about .5 mile on the spur trail. Close inspection reveals an elk wallow near some camas (Camassia Leichtlinii), a lily with an edible bulb, prized by Indians who once gathered the bulbs in large quantities. Continue west through a dark forest growing on a wide terrace above the main tributary of Union Creek. Keen eyes are necessary to locate what is perhaps the largest tree in Crater Lake National Park, a Douglas fir (Psuedotsuga menziesii) measuring 25 feet in circumference.

Big Huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum). |

The ski trail eventually leads to a path heading down slope to the tributary created by Thousand Springs. After a short meander in the wetland you may decide to retrace your steps by using the ski trail, or continue toward the present park boundary. If opting for the latter course, you can loop back to the wagon road by taking a compass bearing set to north. Once on the wagon road, follow it to make a gentle climb going east for about a mile to the old park entrance marked by a concrete monument. The walk back to where you parked on Highway 62 is easier if a small swath cut along the old boundary is followed going north.

Once back at the car, consider going west on the highway several miles to Thousand Springs Sno-Park at milepost 62. From there follow signs on the graveled Forest Highway 60 toward Huckleberry Mountain. A rather dispersed U.S. Forest Service campground is situated near the top, where an abundant supply of huckleberries is usually available at harvest time. You may even encounter tribal members who continue to use this place for berry picking and family gatherings. Please respect their privacy, since these reunions (which can last an afternoon or several days) are vitally important to the people concerned. Not only does the berry harvest serve as a means to gather food, but it also provides an opportunity to tell stories which pass knowledge from one generation to the next. This activity is especially important to the persistence of Klamath tribal identity because the stories are a living link with those who previously passed this way.

The writer gratefully acknowledges Doug Deur and Kelly Kritzer for their review and suggestions.

Notes:

1See “On an Old Road to Crater Lake,” in Nature Notes from Crater Lake 28 (1997) for more detail.

2Two of these sites were described in previous articles by the writer in Nature Notes;these are “A Pause in the Panhandle,” (1996), p. 27, and “The Portals on Whitehorse Creek,” (1999), pp. 32-33.

3One can view this raging cascade up close by descending through the trees. Do not,under any circumstances, attempt to traverse the bare slopes (composed of loosely consolidated pumice and ash) that form the canyon.

4John W. Lund, More Southern Oregon Cross Country Ski Trails (Klamath Falls: the author, 1990), pp. 13-133 has more route detail.

Steve Mark is a National Park Service historian who serves Crater Lake National Park and Oregon Caves National Monument.