Pumice Desert Revisited

“There’s nothing growing there.” “It is so barren.” These are the comments usually heard from visitors who travel along the North Entrance Road of Crater Lake National Park and pass through the Pumice Desert.

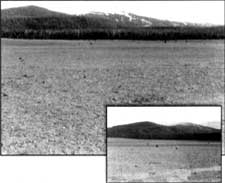

The Pumice Desert is a flat, open area that conspicuously contrasts with the surrounding forest of lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta). A wedge-shaped opening about 5-1/2 square miles in size, the Pumice Desert is covered with material ejected from ancient Mount Mazama. Gaseous materials filled the valleys and depressions surrounding the flanks of the mountain. The depths of deposits covering the Pumice Desert may be some 200 feet thick. Although it appears flat, small washes are scattered throughout. The two benchmarks probably represent the highest and lowest elevations: 6010 and 5962 feet, respectively.

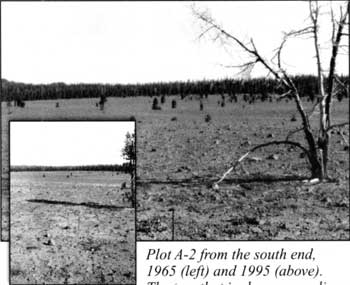

Why has it remained virtually treeless? That was the question posed to me by park staff who suggested that it would be a good project for my masters’ thesis. I therefore initiated an ecological study of the Pumice Desert’s vegetation in 1965. Nine strip plots or transects were marked for future observation. A larger 100-acre plot for tabulating the number of lodgepole pine was also established.

Initial perceptions that nothing will grow in the Pumice Desert are not accurate. It could be said, however, that the vegetation composition is very simple…and very sparse. Some 600 different plant species occur within the boundaries of Crater Lake National Park, but I found only 14 of these growing in the sample plots. (A small lupine, Lupinus lepidus, occurs along the road’s edge, but was not found on any of the research plots).

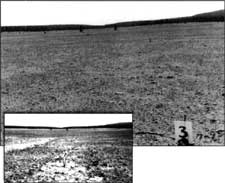

The plants in the vegetative strip plots were sampled in 1965, 1977, and 1995. Although the numbers of individual types of species varied somewhat, the totals did not show a significant trend. The numbers for most species increased in 1977, yet the totals for 1965 and 1995 were very similar. The total coverage was nearly the same for each of the three years: 4.9 to 5 percent of the surface area.

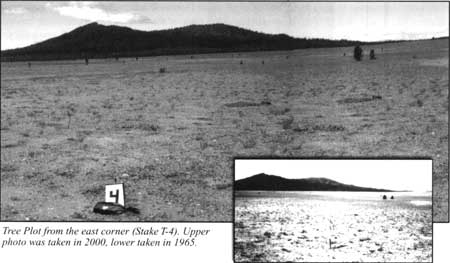

Tree Plot from the east corner (Stake T-4). Upper photo was taken in 2000, lower taken in 1965. Photos courtesy the author.

Many factors can influence the establishment of new plants. A few of them are summarized below:

Soil. Measurements in 1965 showed hot soil temperatures and sterile soil. The deep pumice deposits that filled the valley northwest of Crater Lake make for very poor soil. Compounding this problem is that fact that soil temperatures can be very severe. Although the temperatures of air and at the surface were similar on cloudy days, the soil absorbed a lot of heat on sunny days. During one such day in July, for example, the air temperature did not exceed 83°F—but the soil surface averaged 102°F during a period of six hours. The Pumice Desert was also found to be nutrient deficient compared to pumice soils elsewhere in central Oregon, though soil moisture does not appear to be a controlling factor.

Rodents. An abundance of rodent activity was noted during all fieldwork. Given that gophers are known to destroy the root system of young seedlings where trees are placed in plantations, the sparse vegetation on the Pumice Desert would be an easy food source for the ubiquitous western pocket gopher (Thomomys mazama).

Elements. The climatic extremes and growing season on the Pumice Desert is harsh. As noted above, soil temperatures can be severe. It is reasonable to think that young seeds, whether from lodgepole pine or herbaceous growth, must be able to sprout and survive on the hot, infertile soil and then become established during the short growing season.

Seed source. The majority of new trees observed were relatively close to the forest margin; fewer trees were found toward the center of the Pumice Desert. It is therefore logical to assume that plant succession will proceed most quickly at the edge of the Pumice Desert.

Reproduction. During fieldwork conducted during the summer of 2000, only one tree seedling was found in the strip plots. Once established, the seedling must survive wind, ice, pocket gophers, and other threats. No seedlings were found in the strip plots during fieldwork seasons of 1965 and 1977. Succession cannot proceed when seedlings do not become established.

|

Species of the Pumice Desert The line strips surveyed in 1965 revealed only 14 species growing within the Pumice Desert. Arabis playsperma — Rock cress Arenaria aculeata — Pumice sandwort Aster shastensis — Shasta aster Carex breweri — Brewer’s sedge Carex halliana — Hall’s sedge Calyptridium umbellata — Pussypaws Elymus elymoides — Squirreltail Eriogonum marlium — Mountain buckwheat Hulsea nana — Dwarf hulsea Lomatium martindelei — Lomatium Pinus contorta — Lodgepole pine Polygonum newberryi — Newberry knotweed Viola venosus — Mountain violet |

I found only three lodgepole pines in the strip plots during the initial vegetation survey in 1965. Two of these trees were found in 1977, with a third small tree found in one other plot. An other of the original 1965 trees was dead in 1995, but the new tree found in 1977 could not be located. By 2000 only one of the trees seen in 1965 remained.

All four of the corners on the 100-acre tree plot were marked for future reference in 1965. The plot contained 27 trees that year, with the average tree height being 4.6 feet. The tallest was 9.8 feet, whereas the smallest stood only 8 inches. Many of the trees possessed multiple trunks with soil mounded at the base. There was also much evidence of pocket gopher activity.

When I reexamined the 100-acre tree plot with some colleagues in 2000, we found 47 trees. Most of the increase in tree numbers occurred at the plot’s southeastern end in contrast to the central and north western portions of the plot, where little change was evident. Average height of the trees in 2000 was 8.9 feet, a substantial increase in size and indicating good growth over the intervening 35 years. Heights ranged considerably, with the tallest tree being 49 feet and the smallest less than an inch. As in 1965, many of the trees had multiple stems. Over half of the trees showed mounding of some kind. Only one seedling was found, and it was growing in the drip line of a larger tree.

Plot D-1 from the north end, 1965 (left), 1977 (center), and 1995 (right). The lodgepole pine in this plot is the only one remaining of the three originally found in the vegetative strip plots. Photos courtesy the author.

Many of the trees (29 of 47, as of 2000) in the 100-acre plot showed soil mounding at the base. Mounding can be caused by several factors such as wind-blown soil deposition, frost heave, or animal activity. Most of the Pumice Desert mounds can probably be attributed to wind-blown pumice since the wind blew small granules of pumice across the surface almost constantly during fieldwork. Like sand blowing around plants on a sand dune, fine-grained pumice collects around the base of the trees. Pocket gopher activity might account for some mounds, since distinct signs of these rodents were observed within four feet of roughly half the trees in this plot.

Several trees were cored to determine their age. The four trees drilled were 60 years, 50 years, 66 years, and 40 years of age. Their heights were 19 feet, 23 feet, 18 feet, and 14 feet, respectively. The trees are not easy to age, however, since the tree aged to be 40 years estimated to be 60 years old if the whorls were counted. Similarly, the single remaining tree from the 1965 strip plot had 13 whorls in 1965 and 18 whorls in 1977. If each whorl represented a year’s growth, the tree should have had 25 whorls in 1977.

Many of the trees possessed multiple stems or trunks. Within the 100-acre plot, 31 of the 47 trees displayed this trait. There could be several causes for this characteristic. A rodent could cache seeds that sprout together, or pocket gopher damage on a young tree might lead to multiple branching of an injured stem. Wind and ice damage could injure a young sprout, thereby killing the apical meristem and thus allowing lateral meristems to grow. One of the small dead trees showed a swollen base where wind had removed the surrounding soil. The swollen base is consistent with injury to cambium damaged by wind-driven sand and ice particles. Examination of the broken, swollen base revealed abundant pitch, indicative of a plant trying to seal off an injury and protect the re maining live tissue.

In summary, plant succession on the Pumice Desert is slow but it is indeed proceeding. The number of trees established on the 100-acre plot, for example, has increased by nearly 75 per cent in the 35 years I have been visiting the area. Climate and the elements assure that change will be slow. As soil is built up and existing plants nurture and protect new seedlings, however, it is only a matter of time before the Pumice Desert makes the transition to being forest.

The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of park staff in 1965 for their help with field work, construction of permanent markers, and photographs. Without this cooperation, the project could not have been possible. Special thanks go to Kirk M. Horn, Fred Hall, and William Hopkins for their help, suggestions, and companionship while doing follow-up work on the Pumice Desert in 1977, 1995, and 2000.

References

Elmer I. Applegate, “Plants of Crater Lake National Park,” The American Midland Naturalist 22:2 (September 1939), pp. 225-314.

Elizabeth Mueller Horn, “Ecology of the Pumice Desert,” Northwest Science 42:4 (1968), pp. 141-149.

Ruth Monical and Stephen P. Cross, “Mammals of the Pumice Desert,” Nature Notes from Crater Lake 23 (1992), pp. 17-18.

Elizabeth Mueller Horn recently retired from the U.S. Forest Service, but began her career with the National Park Service as seasonal naturalist at Crater Lake. She is the author of Wildflowers I: The Cascades (Beaverton, Oregon: Touchstone Press, 1972).