Banding Clark’s Nutcrackers

Clark’s Nutcracker. NPS photo. |

In June of 1964 I joined the National Park Service at Crater Lake as one of 13 seasonal interpreters employed that year. As part of our regular duties, each of us was required to spend four hours a week on a research project of our choice. I learned that the park had a bird banding permit and that Clark’s nutcrackers had been banded here sporadically in the past. Since I had been banding birds in my home state of Illinois, I decided to make that my project.

The Clark’s nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana) is a large, noisy gray bird with black wings. This species is related to crows, magpies, ravens, and jays. It can be seen in large numbers along Rim Drive in the areas where people congregate. The birds were well aware of visitor use patterns. Before 10 a.m. and after 4 p.m. there was scarcely a nutcracker to be seen. When the first wave of cars entered the parking lot at Rim Village each day, the birds suddenly appeared. They perched themselves on trees along the promenade and looked for handouts.

Like other species of the Corvidae family, nutcrackers are highly intelligent. I had no information on what methods others had previously used to band birds at Crater Lake, and it took me almost a month to figure out how to catch the birds. I tried several kinds of traps with no success. The nutcrackers refused to step on any kind of trigger mechanism or enter any small opening. It was therefore understandable that the only things I caught with traps were the golden mantled ground squirrels.

One day a fellow interpreter jokingly suggested that I should try the traditional Boy Scout method of trapping. This involved dropping an orange crate over them by pulling on a string. After thinking about this for a while, and wondering if it would work, I decided it was worth a try. I thereby took a large woven wire trap with a sliding door and removed the floor from it. Next, I whittled out a stick about 10 inches long with a notch on one end, and tied a string to the middle of it. I then set one side of the trap up on the stick, and sat a few feet away while holding the end of the string.

I baited the trap with bread and waited, but nothing happened. The birds were all around, eyeing the bait, but they would not go under the trap. I sat there for a while, watching visitors throw peanuts to the nearby birds, and thought “why not?” This prompted me to go to the store inside the cafeteria and buy a can of peanuts. I placed them under the trap, and the birds immediately started to swoop down to get the nuts.1It was easy to pull out the stick and drop the trap on them. I could now reach inside the sliding door and pick up the bird. At this point it was relatively easy to place a band on the bird’s leg and then release it.

I had no trouble catching several birds in a couple of hours using this technique. It was always the action of throwing the nuts that motivated them; they would not come to food that was already on the ground upon their arrival. One capture was enough to teach them a lesson, however, so I never caught the same bird a second time.

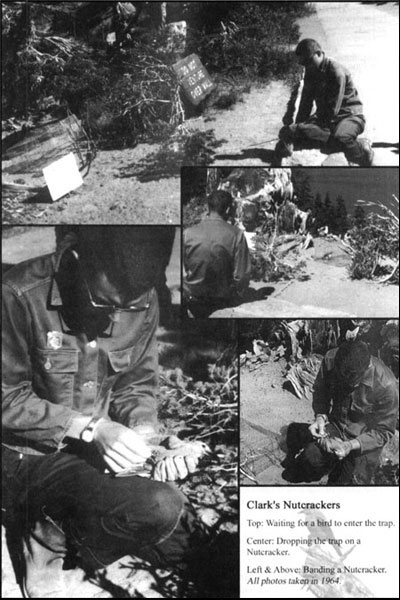

Clark’s Nutcrackers

Top: Waiting for a bird to enter the trap. Center: Dropping the trap on a Nutcracker.

Left & Above: Banding a nutcracker. All photos taken in 1964. Photos courtesy the author.

When I first started trapping, visitors became very indignant because they assumed that I was trying to catch “chipmunks.” It never occurred to them that I might be after the birds. Since I had to watch the trap closely, I could not always turn around and explain what I was doing. I therefore started bringing a small sign that outlined what was happening and this usually satisfied the curiosity of human visitors. The birds would often fly down and sit on the sign while waiting for peanuts, a behavior that seemed rather fitting given the circumstances.

The main obstacle to banding was the seemingly endless supply of hungry golden mantled ground squirrels. They would run under the trap and take the peanuts. As long as the squirrels were there, the birds would stay in the trees and wait. I had to feed the squirrels first in order to get them to take the food back to their caches, then wait until they were all out of sight before throwing more nuts to attract the birds. This wasted a lot of time, to say nothing of running up my bill for the peanuts. By the end of the season I had trapped for a total of 17 days, banded 89 birds, and had seen many other unbanded nutcrackers. As Labor Day came and went, visitation dropped off drastically. Most of the birds disappeared, apparently moving to greener pastures.

The nutcrackers I saw had not been banded for eight years or more prior to my work. I was intrigued to see a few grizzled old birds that had double metal bands on one of their legs. They were frequent observers of the trapping, but for several weeks did not participate. I was finally able to catch two of these “old timers,” and by comparing their band numbers to park records, found they had been banded by Don Farner 12 years earlier.2 The double bands had originally been color-coded to make it easier to track the movements of these birds, but the color had long since worn off by the time I saw them.

Why band the nutcrackers? As with all bird banding, the object was to determine basic life history information such as longevity and patterns of movement. Chief Park Naturalist Dick Brown continued with the banding in subsequent years and eventually published a summary of his findings. He found that two birds he re-trapped were well past 16 years old, a new longevity record for the species.3

Golden Mantled Ground Squirrel. NPS photo.

Notes:

1Feeding wildlife is, of course, against park regulations.

2See pp. 83-89 in Donald S. Farner, Birds of Crater Lake National Park (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1952) for information on Clark’s nutcrackers and banding.

3Richard McP. Brown, “Clark’s Nutcrackers at Crater Lake”, Western Bird Bander 43:2(April 1968). pp. 15-17

Neal Bullington started his career as a seasonal naturalist at Crater Lake in 1965. He is currently the Chief of Interpretation at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Seashore in Empire, Michigan.